Vulvovaginal Candidiasis: a Current Understanding and Burning Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cidara-IFI-Infogr-12.Pdf

We often think of fungal infections as simply bothersome conditions such as athlete’s foot or toenail fungus. But certain types of fungal infections, known as “ ”( ), can be dangerous and fatal. IFIs are systemic and are typically caused when fungi invade the body in various ways such as through the bloodstream or by the inhalation of spores. IFIs can also spread to many other organs such as the liver and kidney. They are associated with ( ) > % • Invasive candidiasis ( ) is a common hospital-acquired infection in the U.S., % cases each year.v • Invasive aspergillosis () occurs most often in people with weakened immune systems or lung disease, and its prevalence is vi An increasing number of people in the U.S. have putting them at greater risk for IFIs.x High-risk groups include: hospitalized patients cancer or transplant patients patients undergoing surgery patients with chronic diseases Rates of invasive candidiasis are dicult ( )is an emerging drug-resistant to estimate and can vary based on time, fungus that spreads quickly and has caused serious region, and study type. and deadly infections in over a dozen countries. + Still, it is clear that overall The CDC estimates that remain high – especially in the U.S. with invasive ix among viii There is an increasingly urgent need to develop new therapies for IFIs, Currently available treatments for IFIs have signicant limitations such as: • toxicities/side eects • inconsistent achievement of target drug levels • interactions with other drugs • increasing microbial resistance As the urgency around IFIs rises, multiple biopharma companies and researchers are working to develop new therapies to treat and prevent them. -

Austin Ultrahealth Yeast-Free Protocol 1

1 01/16/12/ Austin UltraHealth Yeast-Free Protocol 1. Follow the Yeast Diet in your binder for 6 weeks or you may also use recipes from the Elimination Diet. (Just decrease the amount of grains and fruits allowed). 2. You will be taking one pill of prescription antifungal daily, for 30 days. This should always be taken two hours away from your probiotics. This medication can be very hard on your liver so it is important to refrain from ALL alcohol while taking this medication. Candida Die-Off Some patients experience die-off symptoms while eliminating the yeast, or Candida, in their gut. Die off symptoms can include the following: Brain fog Dizziness Headache Floaters in the eyes Anxiety/Irritability Gas, bloating and/or flatulence Diarrhea or constipation Joint/muscle pain General malaise or exhaustion What Causes Die-Off Symptoms? The Candida “die-off” occurs when excess yeast in the body literally dies off. When this occurs, the dying yeasts produce toxins at a rate too fast for your body to process and eliminate. While these toxins are not lethal to the system, they can cause an increase in the symptoms you might already have been experiencing. As the body works to detoxify, those Candida die-off symptoms can emerge and last for a matter of days, or weeks. The two main factors which cause the unpleasant symptoms of Candida die off are dietary changes and antifungal treatments, both of which you will be doing. Dietary Changes: When you begin to make healthy changes in your diet, you begin to starve the excess yeasts that have been hanging around, using up the extra sugars in your blood. -

Oral Candidiasis: a Review

International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences ISSN- 0975-1491 Vol 2, Issue 4, 2010 Review Article ORAL CANDIDIASIS: A REVIEW YUVRAJ SINGH DANGI1, MURARI LAL SONI1, KAMTA PRASAD NAMDEO1 Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Guru Ghasidas Central University, Bilaspur (C.G.) – 49500 Email: [email protected] Received: 13 Jun 2010, Revised and Accepted: 16 July 2010 ABSTRACT Candidiasis, a common opportunistic fungal infection of the oral cavity, may be a cause of discomfort in dental patients. The article reviews common clinical types of candidiasis, its diagnosis current treatment modalities with emphasis on the role of prevention of recurrence in the susceptible dental patient. The dental hygienist can play an important role in education of patients to prevent recurrence. The frequency of invasive fungal infections (IFIs) has increased over the last decade with the rise in at‐risk populations of patients. The morbidity and mortality of IFIs are high and management of these conditions is a great challenge. With the widespread adoption of antifungal prophylaxis, the epidemiology of invasive fungal pathogens has changed. Non‐albicans Candida, non‐fumigatus Aspergillus and moulds other than Aspergillus have become increasingly recognised causes of invasive diseases. These emerging fungi are characterised by resistance or lower susceptibility to standard antifungal agents. Oral candidiasis is a common fungal infection in patients with an impaired immune system, such as those undergoing chemotherapy for cancer and patients with AIDS. It has a high morbidity amongst the latter group with approximately 85% of patients being infected at some point during the course of their illness. A major predisposing factor in HIV‐infected patients is a decreased CD4 T‐cell count. -

Candida Auris

microorganisms Review Candida auris: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Pathogenesis, Antifungal Susceptibility, and Infection Control Measures to Combat the Spread of Infections in Healthcare Facilities Suhail Ahmad * and Wadha Alfouzan Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Kuwait University, P.O. Box 24923, Safat 13110, Kuwait; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +965-2463-6503 Abstract: Candida auris, a recently recognized, often multidrug-resistant yeast, has become a sig- nificant fungal pathogen due to its ability to cause invasive infections and outbreaks in healthcare facilities which have been difficult to control and treat. The extraordinary abilities of C. auris to easily contaminate the environment around colonized patients and persist for long periods have recently re- sulted in major outbreaks in many countries. C. auris resists elimination by robust cleaning and other decontamination procedures, likely due to the formation of ‘dry’ biofilms. Susceptible hospitalized patients, particularly those with multiple comorbidities in intensive care settings, acquire C. auris rather easily from close contact with C. auris-infected patients, their environment, or the equipment used on colonized patients, often with fatal consequences. This review highlights the lessons learned from recent studies on the epidemiology, diagnosis, pathogenesis, susceptibility, and molecular basis of resistance to antifungal drugs and infection control measures to combat the spread of C. auris Citation: Ahmad, S.; Alfouzan, W. Candida auris: Epidemiology, infections in healthcare facilities. Particular emphasis is given to interventions aiming to prevent new Diagnosis, Pathogenesis, Antifungal infections in healthcare facilities, including the screening of susceptible patients for colonization; the Susceptibility, and Infection Control cleaning and decontamination of the environment, equipment, and colonized patients; and successful Measures to Combat the Spread of approaches to identify and treat infected patients, particularly during outbreaks. -

Candida Species Identification by NAA

Candida Species Identification by NAA Background Vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) occurs as a result of displacement of the normal vaginal flora by species of the fungal genus Candida, predominantly Candida albicans. The usual presentation is irritation, itching, burning with urination, and thick, whitish discharge.1 VVC accounts for about 17% to 39% of vaginitis1, and most women will be diagnosed with VVC at least once during their childbearing years.2 In simplistic terms, VVC can be classified into uncomplicated or complicated presentations. Uncomplicated VVC is characterized by infrequent symptomatic episodes, mild to moderate symptoms, or C albicans infection occurring in nonpregnant and immunocompetent women.1 Complicated VVC, in contrast, is typified by severe symptoms, frequent recurrence, infection with Candida species other than C albicans, and/or occurrence during pregnancy or in women with immunosuppression or other medical conditions.1 Diagnosis and Treatment of VVC Traditional diagnosis of VVC is accomplished by either: (i) direct microscopic visualization of yeast-like cells with or without pseudohyphae; or (ii) isolation of Candida species by culture from a vaginal sample.1 Direct microscopy sensitivity is about 50%1 and does not provide a species identification, while cultures can have long turnaround times. Today, nucleic acid amplification-based (NAA) tests (eg, PCR) for Candida species can provide high-quality diagnostic information with quicker turnaround times and can also enable investigation of common potential etiologies -

Candida & Nutrition

Candida & Nutrition Presented by: Pennina Yasharpour, RDN, LDN Registered Dietitian Dickinson College Kline Annex Email: [email protected] What is Candida? • Candida is a type of yeast • Most common cause of fungal infections worldwide Candida albicans • Most common species of candida • C. albicans is part of the normal flora of the mucous membranes of the respiratory, gastrointestinal and female genital tracts. • Causes infections Candidiasis • Overgrowth of candida can cause superficial infections • Commonly known as a “yeast infection” • Mouth, skin, stomach, urinary tract, and vagina • Oropharyngeal candidiasis (thrush) • Oral infections, called oral thrush, are more common in infants, older adults, and people with weakened immune systems • Vulvovaginal candidiasis (vaginal yeast infection) • About 75% of women will get a vaginal yeast infection during their lifetime Causes of Candidiasis • Humans naturally have small amounts of Candida that live in the mouth, stomach, and vagina and don't cause any infections. • Candidiasis occurs when there's an overgrowth of the fungus RISK FACTORS WEAKENED ASSOCIATED IMUMUNE SYSTEM FACTORS • HIV/AIDS (Immunosuppression) • Infants • Diabetes • Elderly • Corticosteroid use • Antibiotic use • Contraceptives • Increased estrogen levels Type 2 Diabetes – Glucose in vaginal secretions promote Yeast growth. (overgrowth) Treatment • Antifungal medications • Oral rinses and tablets, vaginal tablets and suppositories, and creams. • For vaginal yeast infections, medications that are available over the counter include creams and suppositories, such as miconazole (Monistat), ticonazole (Vagistat), and clotrimazole (Gyne-Lotrimin). • Your doctor may prescribe a pill, fluconazole (Diflucan). The Candida Diet • Avoid carbohydrates: Supporters believe that Candida thrives on simple sugars and recommend removing them, along with low-fiber carbohydrates (eg, white bread). -

Fungi in Bronchiectasis: a Concise Review

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Fungi in Bronchiectasis: A Concise Review Luis Máiz 1, Rosa Nieto 1 ID , Rafael Cantón 2 ID , Elia Gómez G. de la Pedrosa 2 and Miguel Ángel Martinez-García 3,* ID 1 Servicio de Neumología, Unidad de Bronquiectasias y Fibrosis Quística, Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal, 28034 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (L.M.); [email protected] (R.N.) 2 Servicio de Microbiología, Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal and Instituto Ramón y Cajal de Investigación Sanitaria (IRYCIS), 28034 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] (R.C.); [email protected] (E.G.G.d.l.P.) 3 Servicio de Neumología, Hospital Universitario y Politécnico la Fe, 46016 Valencia, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-60-986-5934 Received: 3 December 2017; Accepted: 31 December 2017; Published: 4 January 2018 Abstract: Although the spectrum of fungal pathology has been studied extensively in immunosuppressed patients, little is known about the epidemiology, risk factors, and management of fungal infections in chronic pulmonary diseases like bronchiectasis. In bronchiectasis patients, deteriorated mucociliary clearance—generally due to prior colonization by bacterial pathogens—and thick mucosity propitiate, the persistence of fungal spores in the respiratory tract. The most prevalent fungi in these patients are Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus; these are almost always isolated with bacterial pathogens like Haemophillus influenzae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, making very difficult to define their clinical significance. Analysis of the mycobiome enables us to detect a greater diversity of microorganisms than with conventional cultures. The results have shown a reduced fungal diversity in most chronic respiratory diseases, and that this finding correlates with poorer lung function. -

Managing Athlete's Foot

South African Family Practice 2018; 60(5):37-41 S Afr Fam Pract Open Access article distributed under the terms of the ISSN 2078-6190 EISSN 2078-6204 Creative Commons License [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0] © 2018 The Author(s) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 REVIEW Managing athlete’s foot Nkatoko Freddy Makola,1 Nicholus Malesela Magongwa,1 Boikgantsho Matsaung,1 Gustav Schellack,2 Natalie Schellack3 1 Academic interns, School of Pharmacy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University 2 Clinical research professional, pharmaceutical industry 3 Professor, School of Pharmacy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University *Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract This article is aimed at providing a succinct overview of the condition tinea pedis, commonly referred to as athlete’s foot. Tinea pedis is a very common fungal infection that affects a significantly large number of people globally. The presentation of tinea pedis can vary based on the different clinical forms of the condition. The symptoms of tinea pedis may range from asymptomatic, to mild- to-severe forms of pain, itchiness, difficulty walking and other debilitating symptoms. There is a range of precautionary measures available to prevent infection, and both oral and topical drugs can be used for treating tinea pedis. This article briefly highlights what athlete’s foot is, the different causes and how they present, the prevalence of the condition, the variety of diagnostic methods available, and the pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of the -

Oral Antifungals Month/Year of Review: July 2015 Date of Last

© Copyright 2012 Oregon State University. All Rights Reserved Drug Use Research & Management Program Oregon State University, 500 Summer Street NE, E35 Salem, Oregon 97301-1079 Phone 503-947-5220 | Fax 503-947-1119 Class Update with New Drug Evaluation: Oral Antifungals Month/Year of Review: July 2015 Date of Last Review: March 2013 New Drug: isavuconazole (a.k.a. isavunconazonium sulfate) Brand Name (Manufacturer): Cresemba™ (Astellas Pharma US, Inc.) Current Status of PDL Class: See Appendix 1. Dossier Received: Yes1 Research Questions: Is there any new evidence of effectiveness or safety for oral antifungals since the last review that would change current PDL or prior authorization recommendations? Is there evidence of superior clinical cure rates or morbidity rates for invasive aspergillosis and invasive mucormycosis for isavuconazole over currently available oral antifungals? Is there evidence of superior safety or tolerability of isavuconazole over currently available oral antifungals? • Is there evidence of superior effectiveness or safety of isavuconazole for invasive aspergillosis and invasive mucormycosis in specific subpopulations? Conclusions: There is low level evidence that griseofulvin has lower mycological cure rates and higher relapse rates than terbinafine and itraconazole for adult 1 onychomycosis.2 There is high level evidence that terbinafine has more complete cure rates than itraconazole (55% vs. 26%) for adult onychomycosis caused by dermatophyte with similar discontinuation rates for both drugs.2 There is low -

Fungal Infections – an Overview

REVIEW Fungal infections – An overview Natalie Schellack, BCur, BPharm, PhD(Pharmacy); Jade du Toit, BPharm; Tumelo Mokoena, BPharm; Elmien Bronkhorst, BPharm, MSc(Med) School of Pharmacy, Faculty of Health Sciences, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University Correspondence to: Prof Natalie Schellack, [email protected] Abstract Fungi normally originate from the environment that surrounds us, and appear to be harmless until inhaled or ingestion of spores occurs. A pathogenic fungus may lead to infection. People who are at risk of acquiring fungal infection are those living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cancer, receiving immunosuppressant therapy, neonates and those of advanced age. The management of superficial fungal infections is mainly topical, with agents including terbinafine, miconazole and ketoconazole. Oral treatment includes griseofulvin and fluconazole. Invasive fungal infections are difficult to treat, and are managed with agents including the azoles, echinocandins and amphotericin B. This paper provides a general overview of the management of fungus infections. © Medpharm S Afr Pharm J 2019;86(1):33-40 Introduction more advanced biochemical or molecular testing.4 Fungi normally originate from the environment that surrounds Superficial fungal infections us, and appear to be harmless until inhaled or ingestion of spores Either yeasts or fungi can cause dermatomycosis, or superficial occurs. Infection with fungi is also more likely when the body’s fungal infections.7 Fungi that infect the hair, skin, nails and mucosa immune system becomes weakened. A pathogenic fungus may lead to infection. The number of fungus species ranges in the can cause a superficial fungal infection. Dermatophytes are found millions and only a few species seem to be harmful to humans; the naturally in soil, human skin and keratin-containing structures, 3 ones found mostly on the mucous membrane and the skin have which provide them with a source of nutrition. -

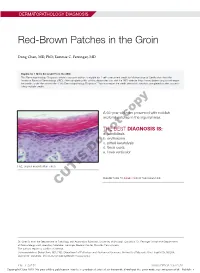

Red-Brown Patches in the Groin

DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS Red-Brown Patches in the Groin Dong Chen, MD, PhD; Tammie C. Ferringer, MD Eligible for 1 MOC SA Credit From the ABD This Dermatopathology Diagnosis article in our print edition is eligible for 1 self-assessment credit for Maintenance of Certification from the American Board of Dermatology (ABD). After completing this activity, diplomates can visit the ABD website (http://www.abderm.org) to self-report the credits under the activity title “Cutis Dermatopathology Diagnosis.” You may report the credit after each activity is completed or after accumu- lating multiple credits. A 66-year-old man presented with reddish arciform patchescopy in the inguinal area. THE BEST DIAGNOSIS IS: a. candidiasis b. noterythrasma c. pitted keratolysis d. tinea cruris Doe. tinea versicolor H&E, original magnification ×600. PLEASE TURN TO PAGE 419 FOR THE DIAGNOSIS CUTIS Dr. Chen is from the Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia. Dr. Ferringer is from the Departments of Dermatology and Laboratory Medicine, Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, Pennsylvania. The authors report no conflict of interest. Correspondence: Dong Chen, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, One Hospital Dr, MA204, DC018.00, Columbia, MO 65212 ([email protected]). 416 I CUTIS® WWW.MDEDGE.COM/CUTIS Copyright Cutis 2018. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted without the prior written permission of the Publisher. DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS DISCUSSION THE DIAGNOSIS: Erythrasma rythrasma usually involves intertriginous areas surface (Figure 1) compared to dermatophyte hyphae that (eg, axillae, groin, inframammary area). Patients tend to be parallel to the surface.2 E present with well-demarcated, minimally scaly, red- Pitted keratolysis is a superficial bacterial infection brown patches. -

Fungal Sepsis: Optimizing Antifungal Therapy in the Critical Care Setting

Fungal Sepsis: Optimizing Antifungal Therapy in the Critical Care Setting a b,c, Alexander Lepak, MD , David Andes, MD * KEYWORDS Invasive candidiasis Pharmacokinetics-pharmacodynamics Therapy Source control Invasive fungal infections (IFI) and fungal sepsis in the intensive care unit (ICU) are increasing and are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality. In this setting, IFI are predominantly caused by Candida species. Currently, candidemia represents the fourth most common health care–associated blood stream infection.1–3 With increasingly immunocompromised patient populations, other fungal species such as Aspergillus species, Pneumocystis jiroveci, Cryptococcus, Zygomycetes, Fusarium species, and Scedosporium species have emerged.4–9 However, this review focuses on invasive candidiasis (IC). Multiple retrospective studies have examined the crude mortality in patients with candidemia and identified rates ranging from 46% to 75%.3 In many instances, this is partly caused by severe underlying comorbidities. Carefully matched, retrospective cohort studies have been undertaken to estimate mortality attributable to candidemia and report rates ranging from 10% to 49%.10–15 Resource use associated with this infection is also significant. Estimates from numerous studies suggest the added hospital cost is as much as $40,000 per case.10–12,16–20 Overall attributable costs are difficult to calculate with precision, but have been estimated to be close to 1 billion dollars in the United States annually.21 a University of Wisconsin, MFCB, Room 5218, 1685 Highland Avenue, Madison, WI 53705-2281, USA b Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin, MFCB, Room 5211, 1685 Highland Avenue, Madison, WI 53705-2281, USA c Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Wisconsin, MFCB, Room 5211, 1685 Highland Avenue, Madison, WI 53705-2281, USA * Corresponding author.