Tinea Capitis 2014 L.C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Estimated Burden of Serious Fungal Infections in Ghana

Journal of Fungi Article Estimated Burden of Serious Fungal Infections in Ghana Bright K. Ocansey 1, George A. Pesewu 2,*, Francis S. Codjoe 2, Samuel Osei-Djarbeng 3, Patrick K. Feglo 4 and David W. Denning 5 1 Laboratory Unit, New Hope Specialist Hospital, Aflao 00233, Ghana; [email protected] 2 Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, School of Biomedical and Allied Health Sciences, College of Health Sciences, University of Ghana, P.O. Box KB-143, Korle-Bu, Accra 00233, Ghana; [email protected] 3 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, Kumasi Technical University, P.O. Box 854, Kumasi 00233, Ghana; [email protected] 4 Department of Clinical Microbiology, School of Medical Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi 00233, Ghana; [email protected] 5 National Aspergillosis Centre, Wythenshawe Hospital and the University of Manchester, Manchester M23 9LT, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +233-277-301-300; Fax: +233-240-190-737 Received: 5 March 2019; Accepted: 14 April 2019; Published: 11 May 2019 Abstract: Fungal infections are increasingly becoming common and yet often neglected in developing countries. Information on the burden of these infections is important for improved patient outcomes. The burden of serious fungal infections in Ghana is unknown. We aimed to estimate this burden. Using local, regional, or global data and estimates of population and at-risk groups, deterministic modelling was employed to estimate national incidence or prevalence. Our study revealed that about 4% of Ghanaians suffer from serious fungal infections yearly, with over 35,000 affected by life-threatening invasive fungal infections. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. In the book, we use the terms ‘fungal infections’ and ‘mycoses’ (or singular fungal infection and mycosis) interchangeably, mostly following the usage of our historical actors in time and place. 2. The term ‘ringworm’ is very old and came from the circular patches of peeled, inflamed skin that characterised the infection. In medicine at least, no one understood it to be associated with worms of any description. 3. Porter, R., ‘The patient’s view: Doing medical history from below’, Theory and Society, 1985, 14: 175–198; Condrau, F., ‘The patient’s view meets the clinical gaze’, Social History of Medicine, 2007, 20: 525–540. 4. Burnham, J. C., ‘American medicine’s golden age: What happened to it?’, Sci- ence, 1982, 215: 1474–1479; Brandt, A. M. and Gardner, M., ‘The golden age of medicine’, in Cooter, R. and Pickstone, J. V., eds, Medicine in the Twentieth Century, Amsterdam, Harwood, 2000, 21–38. 5. The Oxford English Dictionary states that the first use of ‘side-effect’ was in 1939, in H. N. G. Wright and M. L. Montag’s textbook: Materia Med Pharma- col & Therapeutics, 112, when it referred to ‘The effects which are not desired in any particular case are referred to as “side effects” or “side actions” and, in some instances, these may be so powerful as to limit seriously the therapeutic usefulness of the drug.’ 6. Illich, I., Medical Nemesis: The Expropriation of Health, London, Calder & Boyars, 1975. 7. Beck, U., Risk Society: Towards a New Society, New Delhi, Sage, 1992, 56 and 63; Greene, J., Prescribing by Numbers: Drugs and the Definition of Dis- ease, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007; Timmermann, C., ‘To treat or not to treat: Drug research and the changing nature of essential hypertension’, Schlich, T. -

Fungal Infections from Human and Animal Contact

Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews Volume 4 Issue 2 Article 4 4-25-2017 Fungal Infections From Human and Animal Contact Dennis J. Baumgardner Follow this and additional works at: https://aurora.org/jpcrr Part of the Bacterial Infections and Mycoses Commons, Infectious Disease Commons, and the Skin and Connective Tissue Diseases Commons Recommended Citation Baumgardner DJ. Fungal infections from human and animal contact. J Patient Cent Res Rev. 2017;4:78-89. doi: 10.17294/2330-0698.1418 Published quarterly by Midwest-based health system Advocate Aurora Health and indexed in PubMed Central, the Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews (JPCRR) is an open access, peer-reviewed medical journal focused on disseminating scholarly works devoted to improving patient-centered care practices, health outcomes, and the patient experience. REVIEW Fungal Infections From Human and Animal Contact Dennis J. Baumgardner, MD Aurora University of Wisconsin Medical Group, Aurora Health Care, Milwaukee, WI; Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, Madison, WI; Center for Urban Population Health, Milwaukee, WI Abstract Fungal infections in humans resulting from human or animal contact are relatively uncommon, but they include a significant proportion of dermatophyte infections. Some of the most commonly encountered diseases of the integument are dermatomycoses. Human or animal contact may be the source of all types of tinea infections, occasional candidal infections, and some other types of superficial or deep fungal infections. This narrative review focuses on the epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of anthropophilic dermatophyte infections primarily found in North America. -

Estimated Burden of Fungal Infections in Oman

Journal of Fungi Article Estimated Burden of Fungal Infections in Oman Abdullah M. S. Al-Hatmi 1,2,3,* , Mohammed A. Al-Shuhoumi 4 and David W. Denning 5 1 Department of microbiology, Natural & Medical Sciences Research Center, University of Nizwa, Nizwa 616, Oman 2 Department of microbiology, Centre of Expertise in Mycology Radboudumc/CWZ, 6500 Nijmegen, The Netherlands 3 Foundation of Atlas of Clinical Fungi, 1214GP Hilversum, The Netherlands 4 Ibri Hospital, Ministry of Health, Ibri 115, Oman; [email protected] 5 Manchester Fungal Infection Group, Manchester Academic Health Science Centre, The University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PL, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +968-25446328; Fax: +968-25446612 Abstract: For many years, fungi have emerged as significant and frequent opportunistic pathogens and nosocomial infections in many different populations at risk. Fungal infections include disease that varies from superficial to disseminated infections which are often fatal. No fungal disease is reportable in Oman. Many cases are admitted with underlying pathology, and fungal infection is often not documented. The burden of fungal infections in Oman is still unknown. Using disease frequencies from heterogeneous and robust data sources, we provide an estimation of the incidence and prevalence of Oman’s fungal diseases. An estimated 79,520 people in Oman are affected by a serious fungal infection each year, 1.7% of the population, not including fungal skin infections, chronic fungal rhinosinusitis or otitis externa. These figures are dominated by vaginal candidiasis, followed by allergic respiratory disease (fungal asthma). An estimated 244 patients develop invasive aspergillosis and at least 230 candidemia annually (5.4 and 5.0 per 100,000). -

Standard Methods for Fungal Brood Disease Research Métodos Estándar Para La Investigación De Enfermedades Fúngicas De La Cr

Journal of Apicultural Research 52(1): (2013) © IBRA 2013 DOI 10.3896/IBRA.1.52.1.13 REVIEW ARTICLE Standard methods for fungal brood disease research Annette Bruun Jensen1*, Kathrine Aronstein2, José Manuel Flores3, Svjetlana Vojvodic4, María 5 6 Alejandra Palacio and Marla Spivak 1Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of Copenhagen, Thorvaldsensvej 40, 1817 Frederiksberg C, Denmark. 2Honey Bee Research Unit, USDA-ARS, 2413 E. Hwy. 83, Weslaco, TX 78596, USA. 3Department of Zoology, University of Córdoba, Campus Universitario de Rabanales (Ed. C-1), 14071, Córdoba, Spain. 4Center for Insect Science, University of Arizona, 1041 E. Lowell Street, PO Box 210106, Tucson, AZ 85721-0106, USA. 5Unidad Integrada INTA – Facultad de Ciencias Ags, Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, CC 276,7600 Balcarce, Argentina. 6Department of Entomology, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota 55108, USA. Received 1 May 2012, accepted subject to revision 17 July 2012, accepted for publication 12 September 2012. *Corresponding author: Email: [email protected] Summary Chalkbrood and stonebrood are two fungal diseases associated with honey bee brood. Chalkbrood, caused by Ascosphaera apis, is a common and widespread disease that can result in severe reduction of emerging worker bees and thus overall colony productivity. Stonebrood is caused by Aspergillus spp. that are rarely observed, so the impact on colony health is not very well understood. A major concern with the presence of Aspergillus in honey bees is the production of airborne conidia, which can lead to allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, pulmonary aspergilloma, or even invasive aspergillosis in lung tissues upon inhalation by humans. In the current chapter we describe the honey bee disease symptoms of these fungal pathogens. -

Managing Athlete's Foot

South African Family Practice 2018; 60(5):37-41 S Afr Fam Pract Open Access article distributed under the terms of the ISSN 2078-6190 EISSN 2078-6204 Creative Commons License [CC BY-NC-ND 4.0] © 2018 The Author(s) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 REVIEW Managing athlete’s foot Nkatoko Freddy Makola,1 Nicholus Malesela Magongwa,1 Boikgantsho Matsaung,1 Gustav Schellack,2 Natalie Schellack3 1 Academic interns, School of Pharmacy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University 2 Clinical research professional, pharmaceutical industry 3 Professor, School of Pharmacy, Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University *Corresponding author, email: [email protected] Abstract This article is aimed at providing a succinct overview of the condition tinea pedis, commonly referred to as athlete’s foot. Tinea pedis is a very common fungal infection that affects a significantly large number of people globally. The presentation of tinea pedis can vary based on the different clinical forms of the condition. The symptoms of tinea pedis may range from asymptomatic, to mild- to-severe forms of pain, itchiness, difficulty walking and other debilitating symptoms. There is a range of precautionary measures available to prevent infection, and both oral and topical drugs can be used for treating tinea pedis. This article briefly highlights what athlete’s foot is, the different causes and how they present, the prevalence of the condition, the variety of diagnostic methods available, and the pharmacological and non-pharmacological management of the -

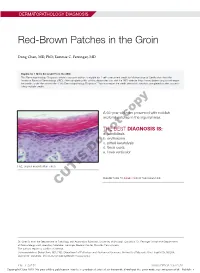

Red-Brown Patches in the Groin

DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS Red-Brown Patches in the Groin Dong Chen, MD, PhD; Tammie C. Ferringer, MD Eligible for 1 MOC SA Credit From the ABD This Dermatopathology Diagnosis article in our print edition is eligible for 1 self-assessment credit for Maintenance of Certification from the American Board of Dermatology (ABD). After completing this activity, diplomates can visit the ABD website (http://www.abderm.org) to self-report the credits under the activity title “Cutis Dermatopathology Diagnosis.” You may report the credit after each activity is completed or after accumu- lating multiple credits. A 66-year-old man presented with reddish arciform patchescopy in the inguinal area. THE BEST DIAGNOSIS IS: a. candidiasis b. noterythrasma c. pitted keratolysis d. tinea cruris Doe. tinea versicolor H&E, original magnification ×600. PLEASE TURN TO PAGE 419 FOR THE DIAGNOSIS CUTIS Dr. Chen is from the Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia. Dr. Ferringer is from the Departments of Dermatology and Laboratory Medicine, Geisinger Medical Center, Danville, Pennsylvania. The authors report no conflict of interest. Correspondence: Dong Chen, MD, PhD, Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, University of Missouri, One Hospital Dr, MA204, DC018.00, Columbia, MO 65212 ([email protected]). 416 I CUTIS® WWW.MDEDGE.COM/CUTIS Copyright Cutis 2018. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted without the prior written permission of the Publisher. DERMATOPATHOLOGY DIAGNOSIS DISCUSSION THE DIAGNOSIS: Erythrasma rythrasma usually involves intertriginous areas surface (Figure 1) compared to dermatophyte hyphae that (eg, axillae, groin, inframammary area). Patients tend to be parallel to the surface.2 E present with well-demarcated, minimally scaly, red- Pitted keratolysis is a superficial bacterial infection brown patches. -

Therapies for Common Cutaneous Fungal Infections

MedicineToday 2014; 15(6): 35-47 PEER REVIEWED FEATURE 2 CPD POINTS Therapies for common cutaneous fungal infections KENG-EE THAI MB BS(Hons), BMedSci(Hons), FACD Key points A practical approach to the diagnosis and treatment of common fungal • Fungal infection should infections of the skin and hair is provided. Topical antifungal therapies always be in the differential are effective and usually used as first-line therapy, with oral antifungals diagnosis of any scaly rash. being saved for recalcitrant infections. Treatment should be for several • Topical antifungal agents are typically adequate treatment weeks at least. for simple tinea. • Oral antifungal therapy may inea and yeast infections are among the dermatophytoses (tinea) and yeast infections be required for extensive most common diagnoses found in general and their differential diagnoses and treatments disease, fungal folliculitis and practice and dermatology. Although are then discussed (Table). tinea involving the face, hair- antifungal therapies are effective in these bearing areas, palms and T infections, an accurate diagnosis is required to ANTIFUNGAL THERAPIES soles. avoid misuse of these or other topical agents. Topical antifungal preparations are the most • Tinea should be suspected if Furthermore, subsequent active prevention is commonly prescribed agents for dermatomy- there is unilateral hand just as important as the initial treatment of the coses, with systemic agents being used for dermatitis and rash on both fungal infection. complex, widespread tinea or when topical agents feet – ‘one hand and two feet’ This article provides a practical approach fail for tinea or yeast infections. The pharmacol- involvement. to antifungal therapy for common fungal infec- ogy of the systemic agents is discussed first here. -

Tinea Capitis: Unusual Chronic Presentation in an Elderly Woman

ISSN: 2474-3658 Salazar et al. J Infect Dis Epidemiol 2018, 4:048 DOI: 10.23937/2474-3658/1510048 Volume 4 | Issue 1 Journal of Open Access Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology CASE REPORT Tinea Capitis: Unusual Chronic Presentation in an Elderly Woman Elizabeth Salazar1*, Daniel Asz-Sigall2, Diana Vega3 and Roberto Arenas4 1Dermato-Oncologist, Private Practice, Mexico City, Mexico 2 Check for Dermatologist, Dermato-Oncology and Trichology Clinic, National University of Mexico, Mexico City, Mexico updates 3Mycologist, Mycology Section, Hospital General “Dr. Manuel Gea González”, Mexico City, Mexico 4Dermatologist and Mycologist, Mycology Section, General Hospital “Dr. Manuel Gea González”, Mexico City, Mexico *Corresponding authors: Elizabeth Salazar, Dermato-Oncologist, Private Practice, Mexico City, Mexico, E-mail: dra. [email protected] The non-inflammatory clinical presentation can be Abstract found in 90% of affected children. It is more frequent in Tinea capitis is a superficial fungal infection of the scalp tropical regions with low socioeconomic conditions and and hair caused by dermatophytes such as Trichophyton and Microsporum. Tinea capitis is very rare in adults, and affects almost exclusively children (98%). The inflamma- may affect those with immunosuppressive diseases or tory form is observed only in 10% and most commonly menopausal elderly women. Clinical manifestations along seen in prepubescent children. Tinea capitis is caused with trichoscopy and Wood’s light, can help the clinician to by dermatophytes that use keratin as a nutrient source. determine the correct diagnosis, in order to reduce irrevers- Scalp erythema, scaling, and crusting are typical signs of ible sequelae and decrease multiple contagion. KOH direct exam and culture confirm diagnosis and aetiology. -

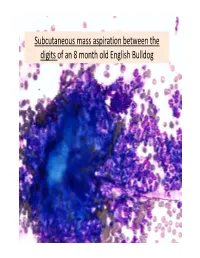

Subcutaneous Mass Aspiration Between the Digits of an 8 Month Old English Bulldog Marked Inflammation: Neutrophils & Macrophages

Subcutaneous mass aspiration between the digits of an 8 month old English Bulldog Marked inflammation: neutrophils & macrophages Hair fragment Macrophages What is this structure? Degenerate Neutrophils Abundant amount of keratin with similar structures The structures are ~ 2‐3 micron in size, blue to occasionally dark purple, oval to round in shape and have a thin clear capsule, consistent with fungal organisms The fungi are seen also in neutrophils and free in the background Growth of Microsporum canis was diagnosed on fungal culture • Microsporum canis is a dermatophyte that frequently causes infection of the superficial layers of skin, hair and nails (dermtophytoses). 1,2 • Microsporum canis, Microsporum gypseum and Trichophyton mentagrophytes are the main etiologic agents of clinical dermatophytosis. 3 • Dermatophytes affect the hair shafts, stratum corneum and nails or claws of animals and people. 2 • The typical lesions include focal alopecia, broken hair shafts, crusts scales and erythema on the head, feet and tail of dogs and cats. 1 • The structures seen in this cytology were Microsporum arthroconidia, which should be differentiated from other similar fungal yeast bodies seen in Candidiasis, Histoplasmosis, Aspergillosis/Penicillosis and Sporotrichosis. 2,4 Kerion • Less commonly dermatophytosis causes raised or dermal nodules called kerions or nodular dermatophytosis. 1,3 • These lesions are formed when the infected hair follicle ruptures and both the fungi and keratin spill in the dermis eliciting an intense inflammatory response. 1 • This may develop in any species but is most commonly reported in dogs. 3 • M. canis is the most common cause of kerion in dogs. 3 • Most common locations were the head, neck and limbs. -

Detection of Histoplasma DNA from Tissue Blocks by a Specific

Journal of Fungi Article Detection of Histoplasma DNA from Tissue Blocks by a Specific and a Broad-Range Real-Time PCR: Tools to Elucidate the Epidemiology of Histoplasmosis Dunja Wilmes 1,*, Ilka McCormick-Smith 1, Charlotte Lempp 2 , Ursula Mayer 2 , Arik Bernard Schulze 3 , Dirk Theegarten 4, Sylvia Hartmann 5 and Volker Rickerts 1 1 Reference Laboratory for Cryptococcosis and Uncommon Invasive Fungal Infections, Division for Mycotic and Parasitic Agents and Mycobacteria, Robert Koch Institute, 13353 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] (I.M.-S.); [email protected] (V.R.) 2 Vet Med Labor GmbH, Division of IDEXX Laboratories, 71636 Ludwigsburg, Germany; [email protected] (C.L.); [email protected] (U.M.) 3 Department of Medicine A, Hematology, Oncology and Pulmonary Medicine, University Hospital Muenster, 48149 Muenster, Germany; [email protected] 4 Institute of Pathology, University Hospital Essen, University Duisburg-Essen, 45147 Essen, Germany; [email protected] 5 Senckenberg Institute for Pathology, Johann Wolfgang Goethe University Frankfurt, 60323 Frankfurt am Main, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-30-187-542-862 Received: 10 November 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2020; Published: 27 November 2020 Abstract: Lack of sensitive diagnostic tests impairs the understanding of the epidemiology of histoplasmosis, a disease whose burden is estimated to be largely underrated. Broad-range PCRs have been applied to identify fungal agents from pathology blocks, but sensitivity is variable. In this study, we compared the results of a specific Histoplasma qPCR (H. qPCR) with the results of a broad-range qPCR (28S qPCR) on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue specimens from patients with proven fungal infections (n = 67), histologically suggestive of histoplasmosis (n = 36) and other mycoses (n = 31). -

Geophilic Dermatophytes and Other Keratinophilic Fungi in the Nests of Wetland Birds

ACTA MyCoLoGICA Vol. 46 (1): 83–107 2011 Geophilic dermatophytes and other keratinophilic fungi in the nests of wetland birds Teresa KoRnIŁŁoWICz-Kowalska1, IGnacy KIToWSKI2 and HELEnA IGLIK1 1Department of Environmental Microbiology, Mycological Laboratory University of Life Sciences in Lublin Leszczyńskiego 7, PL-20-069 Lublin, [email protected] 2Department of zoology, University of Life Sciences in Lublin, Akademicka 13 PL-20-950 Lublin, [email protected] Korniłłowicz-Kowalska T., Kitowski I., Iglik H.: Geophilic dermatophytes and other keratinophilic fungi in the nests of wetland birds. Acta Mycol. 46 (1): 83–107, 2011. The frequency and species diversity of keratinophilic fungi in 38 nests of nine species of wetland birds were examined. nine species of geophilic dermatophytes and 13 Chrysosporium species were recorded. Ch. keratinophilum, which together with its teleomorph (Aphanoascus fulvescens) represented 53% of the keratinolytic mycobiota of the nests, was the most frequently observed species. Chrysosporium tropicum, Trichophyton terrestre and Microsporum gypseum populations were less widespread. The distribution of individual populations was not uniform and depended on physical and chemical properties of the nests (humidity, pH). Key words: Ascomycota, mitosporic fungi, Chrysosporium, occurrence, distribution INTRODUCTION Geophilic dermatophytes and species representing the Chrysosporium group (an arbitrary term) related to them are ecologically classified as keratinophilic fungi. Ke- ratinophilic fungi colonise keratin matter (feathers, hair, etc., animal remains) in the soil, on soil surface and in other natural environments. They are keratinolytic fungi physiologically specialised in decomposing native keratin. They fully solubilise na- tive keratin (chicken feathers) used as the only source of carbon and energy in liquid cultures after 70 to 126 days of growth (20°C) (Korniłłowicz-Kowalska 1997).