Manuscript Cultures Manuscript Cultures Manuscript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Observations on the Nature of Papyrus Bonding

]. Ethnobiol. 11(2):193-202 Winter 1991 SOME OBSERVATIONS ON THE NATURE OF PAPYRUS BONDING PETER E. SCORA Moreno Valley, CA 92360 and RAINER W. SCORA Department of Botany and Plant Sciences University of California Riverside, CA 92521 ABSTRACT.-Papyrus (Cyperus papyrus, Cyperaceae) was a multi-use plant in ancient Egypt. Its main use, however, was for the production of laminated leaves which served as writing material in the Mediterranean world for almost 5000 years. Being a royal monopoly, the manufacturing process was kept secret. PI~us Secundus, who first described this process, is unclear as to the adhesive forces bonding the individual papyrus strips together. Various authors of the past century advanced their own interpretation on bonding. The present authors believe that the natural juices of the papyrus strip are sufficient to bond the individual strips into a sheet, and that any additional paste used was for the sole purpose of pasting the individual dried papyrus sheets into a scroll. RESUMEN.-EI papiro (Cyperus papyrus, Cyperaceae) fue una planta de uso multiple en el antiguo Egipto. Su uso principal era la produccion de hojas lami nadas que sirvieron como material de escritura en el mundo meditarraneo durante casi 5000 anos. Siendo un monopolio real, el proceso de manufactura se mantema en secreto. Plinius Secundus, quien describio este proceso por primera vez, no deja claro que fuerzas adhesivas mantenlan unidas las tiras individuales de papiro. Diversos autores del siglo pasado propusieron sus propias interpretaciones respecto a la adhesion. Consideramos que los jugos naturales de las tiras de papiro son suficientes para adherir las tiras individuales y formar una hoja, y que cual quier pegamento adicional se usa unicamente para unir las hojas secas individuales para formar un rollo. -

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Portraying the Here it is told and put forth how the ancient ones, those called and named Teochichimeca, people of Aztlan, Mexitin, Chicomoz- Aztec Past toca, as they sought and merited the land here, arrived and came into the great altepetl, the altepetl of Mexico Tenochtitlan, the place of renown, the sign, the site of the rock tuna cactus, in the midst of the waters; the place where the eagle rests, where the eagle screeches, where the eagle stretches, where the eagle eats; where the serpent hisses, where the fish fly, where the blue and yellow waters mingle—where the waters burn; where suffering came to be known among the sedges and reeds; the place of encountering and awaiting the various peoples of the four quarters; where the thirteen Teochichimeca arrived and settled, where in misery they settled when they arrived. Behold, here begins, here is to be seen, here lies written, the most excel- lent, most edifying account—the account of [Mexico’s] renown, pride, history, roots, basis, as what is known as the great altepetl began, as it commenced: the city of Mexico Tenochtitlan in the midst of the waters, among the sedges, among the reeds, also called and known as the place where sedges whisper, where reeds whisper. It was becoming the mother, the father, the head of all, of every altepetl everywhere in New Spain, as those who were the ancient ones, men and women, our grandmothers, grandfathers, great-grandfathers, great-great-grandparents, great- grandmothers, our forefathers, told and established in their accounts -

The Pueblos of Morelos in Post- Revolutionary Mexico, 1920-1940

The Dissertation Committee for Salvador Salinas III certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Zapatistas and Their World: The Pueblos of Morelos in Post- revolutionary Mexico, 1920-1940 Committee: ________________________________ Matthew Butler, Supervisor ________________________________ Jonathan Brown ________________________________ Seth Garfield ________________________________ Virginia Garrard-Burnett _________________________________ Samuel Brunk The Zapatistas and Their World: The Pueblos of Morelos in Post- revolutionary Mexico, 1920-1940 by Salvador Salinas III, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2014 To my parents The haciendas lie abandoned; semi-tropical growth burst from a thousand crannies, wreathing these monuments of a dead past in a wilderness of flowers. Green lizards dart through the deserted chapels. The bells which summoned to toil and to worship are silent. The peons are free. But they are not contented. -Ernest Gruening on Morelos, Mexico and its Heritage, New York: Appleton Century Croft, 1928, 162. Acknowledgments First I would like to thank my parents, Linda and Salvador Salinas, for their unwavering support during my graduate studies; to them I dedicate this dissertation. At the University of Texas at Austin, I am greatly indebted to my academic advisor, Dr. Matthew Butler, who for the past six years has provided insightful and constructive feedback on all of my academic work and written many letters of support on my behalf. I am also grateful for my dissertation committee members, Professor Jonathan Brown, Professor Seth Garfield, Professor Virginia Garrard-Burnett, and Professor Samuel Brunk, who all read and provided insightful feedback on this dissertation. -

Christoph Weiditz, the Aztecs, and Feathered Amerindians

Colonial Latin American Review ISSN: 1060-9164 (Print) 1466-1802 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ccla20 Seeking Indianness: Christoph Weiditz, the Aztecs, and feathered Amerindians Elizabeth Hill Boone To cite this article: Elizabeth Hill Boone (2017) Seeking Indianness: Christoph Weiditz, the Aztecs, and feathered Amerindians, Colonial Latin American Review, 26:1, 39-61, DOI: 10.1080/10609164.2017.1287323 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10609164.2017.1287323 Published online: 07 Apr 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 82 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ccla20 Download by: [Library of Congress] Date: 21 August 2017, At: 10:40 COLONIAL LATIN AMERICAN REVIEW, 2017 VOL. 26, NO. 1, 39–61 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10609164.2017.1287323 Seeking Indianness: Christoph Weiditz, the Aztecs, and feathered Amerindians Elizabeth Hill Boone Tulane University In sixteenth-century Europe, it mattered what one wore. For people living in Spain, the Netherlands, Germany, France, and Italy, clothing reflected and defined for others who one was socially and culturally. Merchants dressed differently than peasants; Italians dressed differently than the French.1 Clothing, or costume, was seen as a principal signifier of social identity; it marked different social orders within Europe, and it was a vehicle by which Europeans could understand the peoples of foreign cultures. Consequently, Eur- opeans became interested in how people from different regions and social ranks dressed, a fascination that gave rise in the mid-sixteenth century to a new publishing venture and book genre, the costume book (Figure 1). -

"Comments on the Historicity of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, Tollan, and the Toltecs" by Michael E

31 COMMENTARY "Comments on the Historicity of Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, Tollan, and the Toltecs" by Michael E. Smith University at Albany, State University of New York Can we believe Aztec historical accounts about Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, Tollan, and other Toltec phenomena? The fascinating and important recent exchange in the Nahua Newsletter between H. B. Nicholson and Michel Graulich focused on this question. Stimulated partly by this debate and partly by a recent invitation to contribute an essay to an edited volume on Tula and Chichén Itzá (Smith n.d.), I have taken a new look at Aztec and Maya native historical traditions within the context of comparative oral histories from around the world. This exercise suggests that conquest-period native historical accounts are unlikely to preserve reliable information about events from the Early Postclassic period. Surviving accounts of the Toltecs, the Itzas (prior to Mayapan), Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl, Tula, and Chichén Itzá all belong more to the realm of myth than history. In the spirit of encouraging discussion and debate, I offer a summary here of my views on early Aztec native history; a more complete version of which, including discussion of the Maya Chilam Balam accounts, will be published in Smith (n.d.). I have long thought that Mesoamericanists have been far too credulous in their acceptance of native historical sources; this is an example of what historian David Fischer (1970:58-61) calls "the fallacy of misplaced literalism." Aztec native history was an oral genre that employed painted books as mnemonic devices to aid the historian or scribe in their recitation (Calnek 1978; Nicholson 1971). -

Leafing Through History

Leafing Through History Leafing Through History Several divisions of the Missouri Botanical Garden shared their expertise and collections for this exhibition: the William L. Brown Center, the Herbarium, the EarthWays Center, Horticulture and the William T. Kemper Center for Home Gardening, Education and Tower Grove House, and the Peter H. Raven Library. Grateful thanks to Nancy and Kenneth Kranzberg for their support of the exhibition and this publication. Special acknowledgments to lenders and collaborators James Lucas, Michael Powell, Megan Singleton, Mimi Phelan of Midland Paper, Packaging + Supplies, Dr. Shirley Graham, Greg Johnson of Johnson Paper, and the Campbell House Museum for their contributions to the exhibition. Many thanks to the artists who have shared their work with the exhibition. Especial thanks to Virginia Harold for the photography and Studiopowell for the design of this publication. This publication was printed by Advertisers Printing, one of only 50 U.S. printing companies to have earned SGP (Sustainability Green Partner) Certification, the industry standard for sustainability performance. Copyright © 2019 Missouri Botanical Garden 2 James Lucas Michael Powell Megan Singleton with Beth Johnson Shuki Kato Robert Lang Cekouat Léon Catherine Liu Isabella Myers Shoko Nakamura Nguyen Quyet Tien Jon Tucker Rob Snyder Curated by Nezka Pfeifer Museum Curator Stephen and Peter Sachs Museum Missouri Botanical Garden Inside Cover: Acapulco Gold rolling papers Hemp paper 1972 Collection of the William L. Brown Center [WLBC00199] Previous Page: Bactrian Camel James Lucas 2017 Courtesy of the artist Evans Gallery Installation view 4 Plants comprise 90% of what we use or make on a daily basis, and yet, we overlook them or take them for granted regularly. -

The Palmyrene Prosopography

THE PALMYRENE PROSOPOGRAPHY by Palmira Piersimoni University College London Thesis submitted for the Higher Degree of Doctor of Philosophy London 1995 C II. TRIBES, CLANS AND FAMILIES (i. t. II. TRIBES, CLANS AND FAMILIES The problem of the social structure at Palmyra has already been met by many authors who have focused their interest mainly to the study of the tribal organisation'. In dealing with this subject, it comes natural to attempt a distinction amongst the so-called tribes or family groups, for they are so well and widely attested. On the other hand, as shall be seen, it is not easy to define exactly what a tribe or a clan meant in terms of structure and size and which are the limits to take into account in trying to distinguish them. At the heart of Palmyrene social organisation we find not only individuals or families but tribes or groups of families, in any case groups linked by a common (true or presumed) ancestry. The Palmyrene language expresses the main gentilic grouping with phd2, for which the Greek corresponding word is ØuAi in the bilingual texts. The most common Palmyrene formula is: dynwpbd biiyx... 'who is from the tribe of', where sometimes the word phd is omitted. Usually, the term bny introduces the name of a tribe that either refers to a common ancestor or represents a guild as the Ben Komarê, lit. 'the Sons of the priest' and the Benê Zimrâ, 'the sons of the cantors' 3 , according to a well-established Semitic tradition of attaching the guilds' names to an ancestor, so that we have the corporations of pastoral nomads, musicians, smiths, etc. -

The Bilimek Pulque Vessel (From in His Argument for the Tentative Date of 1 Ozomatli, Seler (1902-1923:2:923) Called Atten- Nicholson and Quiñones Keber 1983:No

CHAPTER 9 The BilimekPulqueVessel:Starlore, Calendrics,andCosmologyof LatePostclassicCentralMexico The Bilimek Vessel of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Vienna is a tour de force of Aztec lapidary art (Figure 1). Carved in dark-green phyllite, the vessel is covered with complex iconographic scenes. Eduard Seler (1902, 1902-1923:2:913-952) was the first to interpret its a function and iconographic significance, noting that the imagery concerns the beverage pulque, or octli, the fermented juice of the maguey. In his pioneering analysis, Seler discussed many of the more esoteric aspects of the cult of pulque in ancient highland Mexico. In this study, I address the significance of pulque in Aztec mythology, cosmology, and calendrics and note that the Bilimek Vessel is a powerful period-ending statement pertaining to star gods of the night sky, cosmic battle, and the completion of the Aztec 52-year cycle. The Iconography of the Bilimek Vessel The most prominent element on the Bilimek Vessel is the large head projecting from the side of the vase (Figure 2a). Noting the bone jaw and fringe of malinalli grass hair, Seler (1902-1923:2:916) suggested that the head represents the day sign Malinalli, which for the b Aztec frequently appears as a skeletal head with malinalli hair (Figure 2b). However, because the head is not accompanied by the numeral coefficient required for a completetonalpohualli Figure 2. Comparison of face date, Seler rejected the Malinalli identification. Based on the appearance of the date 8 Flint on front of Bilimek Vessel with Aztec Malinalli sign: (a) face on on the vessel rim, Seler suggested that the face is the day sign Ozomatli, with an inferred Bilimek Vessel, note malinalli tonalpohualli reference to the trecena 1 Ozomatli (1902-1923:2:922-923). -

“Enclosures with Inclusion” Vis-À-Vis “Boundaries” in Ancient Mexico

Ancient Mesoamerica, page 1 of 16, 2021 Copyright © The Author(s), 2021. Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:10.1017/S0956536121000043 “ENCLOSURES WITH INCLUSION” VIS-À-VIS “BOUNDARIES” IN ANCIENT MEXICO Amos Megged Department of General History, University of Haifa, Mount Carmel, Haifa 31990, Israel Abstract Recent in-depth research on the Nahua Corpus Xolotl, as well as on a large variety of compatible sources, has led to new insights on what were “boundaries” in preconquest Nahua thought. The present article proposes that our modern Western concept of borders and political boundaries was foreign to ancient Mexican societies and to Aztec-era polities in general. Consequently, the article aims to add a novel angle to our understanding of the notions of space, territoriality, and limits in the indigenous worldview in central Mexico during preconquest times, and their repercussions for the internal social and political relations that evolved within the Nahua-Acolhua ethnic states (altepetl). Furthermore, taking its cue from the Corpus Xolotl, the article reconsiders the validity of ethnic entities and polities in ancient Mexico and claims that many of these polities were ethnic and territorial amalgams, in which components of ethnic outsiders formed internal enclaves and powerbases. I argue that in ancient Mexico one is able to observe yet another kind of conceptualization of borders/ frontiers: “enclosures with inclusion,” which served as the indigenous concept of porous and inclusive boundaries, well up to the era of the formation of the so-called Triple Alliance, and beyond. -

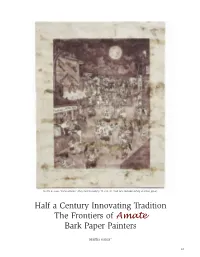

Half a Century Innovating Tradition the Frontiers of Amate Bark Paper Painters

Nicolás de Jesús, “Comierdalismo” (Shitty Commercialism), 75 x 60 cm, 1993 (line and color etching on amate paper). Half a Century Innovating Tradition The Frontiers of Amate Bark Paper Painters Martha García* 41 fter almost 50 years of creating the famous paintings on amate bark paper, Nahua artists have been given yet another well-deserved award for the tradition they have zealously pre- A served from the beginning: the 2007 National Prize for Science and the Arts in the cate- gory of folk arts and traditions. One of the most important characteristics of the continuity of their work has been the innovations they have introduced without abandoning their roots. This has allowed them to enter into the twenty-first century with themes alluding to the day-to-day life of society, like migration, touched on by the work of Tito Rutilo, Nicolás de Jesús, Marcial Camilo and Roberto Mauricio, shown on these pages. In general the Nahua painters of the Alto Balsas in Guerrero state have accustomed the assidu- ous consumer to their colorful “sheets” —as they call the pieces of amate paper— to classic scenes of religious festivities, customs and peasant life that are called “histories”. The other kind of sheet is the “birds and flowers” variety with stylized animals and plants or reproductions of Nahua myths. In part, the national prize given to the Nahua painters and shared by artists who work in lacquer and lead is one more encouragement added to other prizes awarded individually and collectively both in Mexico and abroad. As one of the great legacies of this ancient town, located in the Balsas region for more than a millennium, the communities’ paintings have become a window through which to talk to the world about their profound past and their stirring contemporary experiences. -

Cannibalism and Aztec Human Sacrifice Stephanie Zink May, 2008 a Senior Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Require

CANNIBALISM AND AZTEC HUMAN SACRIFICE STEPHANIE ZINK MAY, 2008 A SENIOR PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN- LA CROSSE Abstract As the nature of Aztec cannibalism is poorly known, this paper examines the extent to which it was practiced and the motives behind it. Using the methodology of documentary research I have determined that the Aztecs did in fact engage in cannibalism, specifically ritual and gustatory cannibalism, however, the extent of it is indefinite. The analysis that I have conducted suggests that, while several hypotheses exist, there is only one that is backed by the evidence: Aztec cannibalism was practiced for religious reasons. In order to better understand this issue, other hypotheses must be examined. 2 Introduction Cannibalism is mostly considered a taboo in western culture, with the exception of sacraments in Christianity, which involve the symbolic eating of the body of Christ and the drinking of Christ’s blood. The general public, in western societies, is disgusted by the thought of humans eating each other, and yet it still seems to fascinate them. Accounts of cannibalism can be found throughout the history of the world from the United States and the Amazon Basin to New Zealand and Indonesia. A few fairly well documented instances of cannibalism include the Aztecs; the Donner Party, a group of pioneers who were trapped while trying to cross the Sierra Nevada Mountains in the winter of 1846-1847; the Uruguayan soccer team that crashed in Chile in 1972 in the Andes Mountains (Hefner, http://www.themystica.com/mystica/articles/c/cannibalism.html). -

Rethinking the Conquest : an Exploration of the Similarities Between Pre-Contact Spanish and Mexica Society, Culture, and Royalty

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2015 Rethinking the Conquest : an exploration of the similarities between pre-contact Spanish and Mexica society, culture, and royalty Samantha Billing University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2015 Samantha Billing Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Latin American History Commons Recommended Citation Billing, Samantha, "Rethinking the Conquest : an exploration of the similarities between pre-contact Spanish and Mexica society, culture, and royalty" (2015). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 155. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/155 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by SAMANTHA BILLING 2015 All Rights Reserved RETHINKING THE CONQUEST: AN EXPLORATION OF THE SIMILARITIES BETWEEN PRE‐CONTACT SPANISH AND MEXICA SOCIETY, CULTURE, AND ROYALTY An Abstract of a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Samantha Billing University of Northern Iowa May 2015 ABSTRACT The Spanish Conquest has been historically marked by the year 1521 and is popularly thought of as an absolute and complete process of indigenous subjugation in the New World. Alongside this idea comes the widespread narrative that describes a barbaric, uncivilized group of indigenous people being conquered and subjugated by a more sophisticated and superior group of Europeans.