Syria: US Withdrawal and Turkish Incursion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Istanbul Technical University Graduate School of Arts

ISTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES TRANSFORMATIONS OF KURDISH MUSIC IN SYRIA: SOCIAL AND POLITICAL FACTORS M.A. THESIS Hussain HAJJ Department of Musicology and Music Theory Musicology M.A. Programme JUNE 2018 ISTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES TRANSFORMATIONS OF KURDISH MUSIC IN SYRIA: SOCIAL AND POLITICAL FACTORS M.A. THESIS Hussain HAJJ (404141007) Department of Musicology and Music Theory Musicology Programme Thesis Advisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. F. Belma KURTİŞOĞLU JUNE 2018 İSTANBUL TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ SURİYE’DE KÜRT MÜZİĞİNİN DÖNÜŞÜMÜ: SOSYAL VE POLİTİK ETKENLER YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ Hussain HAJJ (404141007) Müzikoloji ve Müzik Teorisi Anabilim Dalı Müzikoloji Yüksek Lisans Programı Tez Danışmanı: Doç. Dr. F. Belma KURTİŞOĞLU HAZİRAN 2018 Date of Submission : 7 May 2018 Date of Defense : 4 June 2018 v vi To the memory of my father, to my dear mother and Neslihan Güngör; thanks for always being there for me. vii viii FOREWORD When I started studying Musicology, a musician friend from Syrian Kurds told me that I am leaving my seat as an active musician and starting a life of academic researches, and that he will make music and I will research the music he makes. It was really an interesting statement to me; it made me think of two things, the first one is the intention behind this statement, while the second was the attitude of Kurds, especially Kurd musicians, towards researchers and researching. As for the first thing, I felt that there was a problem, maybe a social or psychological, of the Kurdish people in general, and the musicians in particular. -

Information and Liaison Bulletin

INSTITUT KURD E DE PARIS Information and liaison bulletin N° 380 NOVEMBER 2016 The publication of this Bulletin enjoys a subsidy from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Ministry of Culture This bulletin is issued in French and English Price per issue : France: 6 € — Abroad : 7,5 € Annual subscribtion (12 issues) France : 60 € — Elsewhere : 75 € Monthly review Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN Misen en page et maquette : Ṣerefettin ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tel. : 01-48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01-48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: bulletin@fikp.org Information and liaison bulletin Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 380 November 2016 • ROJAVA: THE SYRIAN DEMOCRATIC FORCES LAUNCH THE ATTACK ON RAQQA — TURKEY IS KEPT OUT OF IT • IRAQ: THE VICE IS TIGHTENING ROUND ISIS IN MOSUL • TURKEY: FURTHER CRACKING DOWN ON THE MEDIA WHILE WAR IS BEING WAGED AGAINST THE KURDS • TURKEY: IMPLACABLE REPRESSION OF THE HDP AND ARREST OF ITS TWO CO-PRESIDENTS • DIYARBAKIR PAYS TRIBUTE TO TAHIR ELÇI, LATE PRESIDENT OF ITS BAR AND DEFENDER OF PEACE, ON THE ANNIVERSARY OF HIS ASSASSI - NATION • PARIS: A SYMPOSIUM AT THE SENATE ON STA - TUS OF CHRISTIANS AND YEZIDIS AFTER THE BATTLE FOR MOSUL ROJAVA: THE SYRIAN DEMOCRATIC FORCES LAUNCH THE ATTACK ON RAQQA — TURKEY IS KEPT OUT OF IT n 3 rd November, Talal Turkey were to take part [in the Wrath ”. The operation, that Silo, spokesman of the advance on Raqqa] it would be to would involve 30,000 fighters, Syrian Democratic help ISIS not to fight it”. -

THE KURDS ASCENDING This Page Intentionally Left Blank the KURDS ASCENDING

THE KURDS ASCENDING This page intentionally left blank THE KURDS ASCENDING THE EVOLVING SOLUTION TO THE KURDISH PROBLEM IN IRAQ AND TURKEY MICHAEL M. GUNTER THE KURDS ASCENDING Copyright © Michael M. Gunter, 2008. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2008 978-0-230-60370-7 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2008 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-0-230-11287-2 ISBN 978-0-230-33894-4 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230338944 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gunter, Michael M. The Kurds ascending : the evolving solution to the Kurdish problem in Iraq and Turkey / Michael M. Gunter. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Kurds—Iraq—Politics and government—21st century. 2. Kurds— Turkey—Politics and government—21st century. I. Title. DS70.8.K8G858 2007 323.1191Ј5970561—dc22 2007015282 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Design by Newgen -

1 Historical Overview

NOTES 1 Historical Overview 1. Possibly the two best studies of the Kurds in English remain Bruinessen, Agha, Shaikh and State; and McDowall, A Modern History of the Kurds. More recently, see Romano, The Kurdish Nationalist Movement; and Natali, The Kurds and the State. Portions of this chapter originally appeared in other articles and chapters I have published including “The Kurdish Problem in International Politics,” in Joseph, Turkey and the European Union, pp. 96–121. 2. For further discussions of the size of the Kurdish population, see McDowall, Modern History of the Kurds, pp. 3–5; Bruinessen, Agha, Shaikh and State, pp. 14–15; and Izady, The Kurds, pp. 111–20. For a detailed analysis that lists considerably smaller figures for Turkey, see Mutlu, “Ethnic Kurds in Turkey,” pp. 517–41. 3. For a solid study of the Sheikh Said revolt, see Olson, The Emergence of Kurdish Nationalism. 4. For a recent detailed analysis of the Kurdish problem in Turkey, see Ozcan, Turkey’s Kurds. 5. “The Sun also Rises in the South East,” pp. 1–2. 6. For a meticulous analysis of the many problems involved, see Yildiz, The Kurds in Turkey, as well as my analysis in chapter 5 of this book. 7. “Ozkok: Biggest Crisis of Trust with US” Turkish Daily News, July 7, 2003; and Nicholas Kralev, “U.S. Warns Turkey against Operations in Northern Iraq.” Washington Times, July 8, 2003. 8. For recent detailed analysis of the Kurdish problem in Iraq, see Stansfield, Iraqi Kurdistan. 140 NOTES 9. For Henry Kissinger’s exact words, see “The CIA Report the President Doesn’t Want You to Read,” The Village Voice, February 16, 1976, pp. -

Nation-State Utopia and Collective Violence of Minorities, a Case Study: PKK from Turkey to Europe Since 1980 to 2013”

MASTERARBEIT Titel der Masterarbeit “Nation-State Utopia and Collective Violence of Minorities, A Case Study: PKK from Turkey to Europe Since 1980 To 2013” Verfasserin Fatma Gül Özen angestrebter akademischer Grad Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2014 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 824 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Masterstudium Politikwissenschaft Betreuter: Doz. Dr. Johann Wimmer 2 3 Acknowledgement I would express my gratitudes to my father Merdan Özen, my mother Kezban Özen and my brother Mert Can Özen for supporting me with their love, and believing in my success from the beginning of my studies in University of Vienna. I would like to thank my supervisor Assist. Prof. Dr. Hannes Wimmer who gave me the chance to work with him on this thesis. With his great supervision and precious encouragement this work has been completed. I would like to send my special thanks to Prof. Dr. Ali Yaşar Sarıbay for his valuable theoretical advices about my thesis. I also thank Prof. Dr. Süleyman Seyfi Öğün for giving me stimulating guidance during my Bachelor's studies. My close friends Gülsüm Cirit, Ahmet Tepehan, and Çimen Akgün have shared my feelings in several difficulties and had fun when I went to Turkey. I would like to thank them for being with me all the time in spite of the long distances. I thank Aydın Karaer, Caner Demirpolat, Ayşe and Furkan Tercan, Nurdan and Idris El-Thalji who made our times enjoyable in Helsinki. I am thankful that Çağdaş Çeçen and Elif Bilici have helped me with the bureaucratic procedures at University of Vienna and made me feel in my old Bachelor's education days in Uludağ University with their sincere conversations on especially theater-cinema and politics. -

The Exclusion of the PYD from the 2016 Geneva III Peace Talks on Syria

Master Thesis The exclusion of the PYD from the 2016 Geneva III peace talks on Syria Causes and Consequences Lisa Gotoh Student number: 10118330 Universiteit van Amsterdam Master: Politicologie Track: Internationale Betrekkingen Supervisor: Said Rezaeiejan Second reader: Liza Mügge Date: June 24, 2016 The Exclusion of the PYD from the 2016 Geneva peace talks on Syria Lisa Gotoh TABLE OF CONTENT Table of Content ............................................................................................................. 2 List of Abbreviations ...................................................................................................... 4 Abstract ........................................................................................................................... 5 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 6 2 Academic and Societal Relevance ........................................................................... 8 3 Theoretical Framework .......................................................................................... 10 3.1 Conflict Resolution and the Hourglass Model ................................................ 11 3.2 Ohlson’s Causes of War and Peace ................................................................ 14 3.3 Mutually Hurting Stalemate ............................................................................ 15 3.4 Mutually Enticing Opportunities ................................................................... -

Iraq in Crisis

Burke Chair in Strategy Iraq in Crisis By Anthony H. Cordesman and Sam Khazai January 6, 2014 Request for comments: This report is a draft that will be turned into an electronic book. Comments and suggested changes would be greatly appreciated. Please send any comments to Anthony H. Cordsman, Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy, at [email protected]. ANTHONY H. CORDESMAN Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy [email protected] Iraq in Crisis: Cordesman and Khazai AHC Final Review Draft 6.1.14 ii Acknowledgements This analysis was written with the assistance of Burke Chair researcher Daniel DeWit. Iraq in Crisis: Cordesman and Khazai AHC Final Review Draft 6.1.14 iii Executive Summary As events in late December 2013 and early 2014 have made brutally clear, Iraq is a nation in crisis bordering on civil war. It is burdened by a long history of war, internal power struggles, and failed governance. Is also a nation whose failed leadership is now creating a steady increase in the sectarian divisions between Shi’ite and Sunni, and the ethnic divisions between Arab and Kurd. Iraq suffers badly from the legacy of mistakes the US made during and after its invasion in 2003. It suffers from threat posed by the reemergence of violent Sunni extremist movements like Al Qaeda and equally violent Shi’ite militias. It suffers from pressure from Iran and near isolation by several key Arab states. It has increasingly become the victim of the forces unleashed by the Syrian civil war. Its main threats, however, are self-inflicted wounds caused by its political leaders. -

Tackling the Conflict Between Turkey and Armed Kurdish Groups

SECURITY COUNCIL Topic 1: Tackling the Conflict between Turkey and Armed Kurdish Groups. Structure: 1. Introduction 2. Definition of key-terms 3. Historical backround 4. Kurds’ situation in other countries 5. Parties involved 6. Possible solutions 7. Bibliography 1. Introduction: The Kurdish–Turkish conflict is an armed conflict between the Republic of Turkey and various Kurdish insurgent groups which have demanded separation from Turkey to create an independent Kurdistan, or to have autonomy and greater political and cultural rights for Kurds inside the Republic of Turkey. 2. Definition of key-terms: The Kurds or the Kurdish people are an Iranian ethnic group, who live across a large contiguous block of the Middle East, which spreads across Iran, Iraq, Syria and Turkey, (area commonly known as Kurdistan). There are 15 to 20 million Kurds, with their own language and culture, living in this territory, slightly more than half of which are in Turkey and form approximately 18% of the population in Turkey. Religiously, Kurds are Sunni Muslims, like the majority of Turkey’s citizens. 3. Historical background, (with emphasis on the situation in Turkey): 3.1. The formation of the Republic of Turkey After the World War I, The Ottoman Empire is liquidated and therefore Turkish sovereignty is abolished by The 1920 Treaty of Sevre. This formed the nations of Iraq, Syria and Kuwait, with the possibility of additionally forming an individual Kurdish Nation. However, Turkey, Iraq and Syria did not recognize the Kurds as an individual group, forcing the Kurds to live as a minority ethnic group within the borders of the newly formed nations. -

Information and Liaison Bulletin

INSTITUT KUDE RPARD IS E Information and liaison bulletin N° 371 FEBRUARY 2016 The publication of this Bulletin enjoys a subsidy from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DGCID) aqnd the Fonds d’action et de soutien pour l’intégration et la lutte contre les discriminations (The Fund for action and support of integration and the struggle against discrimination) This bulletin is issued in French and English Price per issue : France: 6 € — Abroad : 7,5 € Annual subscribtion (12 issues) France : 60 € — Elsewhere : 75 € Monthly review Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN Numéro de la Commission Paritaire : 659 15 A.S. ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tel. : 01-48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01-48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: bulletin@fikp.org Information and liaison bulletin Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 371 February 2016 • TURKEY: A RECORD OF ALL OUT REPRESSION • IRAQI KURDISTAN: ECONOMIC DIFFICULTIES AND A POLITICAL CRISIS • ROJAAVA: WHILE “GENEVA III” FOUNDERS THE KURDISH-ARAB ALLIANCE MAKES FRESH AD - VANCES TURKEY: A RECORD OF ALL OUT REPRESSION st n the 1 of the month covering part of the lens. More - Following publication of this news, the UN Commissioner over, the HDP announced that it while the Turkish Army announced O for Human Rights at had been unable to communicate that it had killed 600 rebels since Geneva expressed in - for the last three days with a group December (it has not been possible dignation and urged of 31 civilians, some of whom to obtain independent confirma - Turkey to conduct an enquiry into were wounded, who had been tion of these figures) the HDP co- the death by shooting of an un - trapped for several weeks in a cel - President, Selahettin Demirtaş, armed group of civilians in Kur - lar in Cizre, which has been under accused the Turkish security forces, th distan. -

Lists of Terrorist Organizations

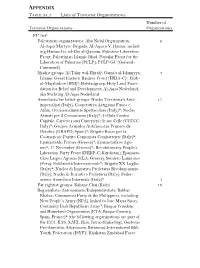

114 Consequences of Counterterrorism APPENDIX TABLE 3A.1 Lists of Terrorist Organizations Number of Terrorist Organizations Organizations EU lista Palestinian organizations: Abu Nidal Organization; 6 Al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigade; Al-Aqsa e.V. Hamas, includ- ing Hamas-Izz ad-Din al-Qassam; Palestine Liberation Front; Palestinian Islamic Jihad; Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP); PFLP-GC (General- Command) Jihadist groups: Al-Takir wal-Hijrahb; Gama’a al-Islamiyya; 7 Islamic Great Eastern Raiders Front (IBDA-C)c; Hizb- ul-Mujahideen (HM)d; Hofstadgroep; Holy Land Foun- dation for Relief and Development; Al-Aqsa Nederland, aka Stichting Al-Aqsa Nederland Anarchists/far leftist groups: Nuclei Territoriali Anti- 17 imperialisti (Italy); Cooperativa Artigiana Fuoco e Affini, Occasionalmente Spettacolare (Italy)*; Nuclei Armati per il Comunismo (Italy)*; Cellula Contro Capitale, Carcere i suci Carcerieri e le sue Celle (CCCCC: Italy)*; Grupos Armados Antifascistas Primero de Octubre (GRAPO; Spain)*; Brigate Rosse per la Costruzione Partito Comunista Combattente (Italy)*; Epanastatiki Pirines (Greece)*; Epanastatikos Ago- nas*; 17 November (Greece)*; Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party Front (DHKP-C; Kurdistan); Epanasta- tikos Laigos Agonas (ELA; Greece); Sendero Luminoso (Peru); Solidarietà Internazionale*; Brigata XX Luglio (Italy)*; Nucleo di Iniziativa Proletaria Rivoluzionaria (Italy); Nuclei di Iniziativa Proletaria (Italy); Feder- azione Anarchica Informale (Italy)* 1 Far rightist groups: Kahane Chai (Kach) 18 Regionalists/Autonomists/Independentists: -

The Functioning of Democratic Institutions in Turkey

Provisional version 23 May 2016 The functioning of democratic institutions in Turkey Committee on the Honouring of Obligations and Commitments by Member States of the Council of Europe (Monitoring Committee) Co-rapporteurs: Ms Ingebjørg Godskesen, Norway, European Conservatives Group, and Ms Nataša Vučković, Serbia, Socialist Group Draft resolution1 1. Turkey has been under post-monitoring dialogue with the Assembly since 2004. In its Resolution 1925 of April 2013, the Assembly encouraged Turkey, a founding member of the Council of Europe and strategic partner for Europe, to pursue its efforts to align its legislation and practices with Council of Europe standards and fulfill the remaining post-monitoring dialogue requirements. Turkey has continued to face a complex and adverse geopolitical situation with the war in Syria and in the surrounding countries and terrorist attacks on its territory. The on-going conflict in Syria has brought further massive flows of refugees to Turkey. The Assembly reiterates its appreciation of the outstanding efforts made by the country since 2011 to host nearly 3 million refugees (among which 262 000 are in refugee camps), who are in need of accommodation, education and access to social and medical care. For over five years, Turkey has been implementing the "open door policy" to the Syrians who fled from the war environment in their country and in compliance with its international obligations, has abided by the principle of “non-refoulement". The Assembly expresses its appreciation of the measures taken by the Turkish authorities to improve the living conditions of Syrian refugees, in particular by allocating work permits since 15 January 2016. -

Turkey COI Compilation 2020

Turkey: COI Compilation August 2020 BEREICH | EVENTL. ABTEILUNG | WWW.ROTESKREUZ.AT ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Turkey: COI Compilation August 2020 The information in this report is up to date as of 30 April 2020, unless otherwise stated. This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared within a specified time frame on the basis of publicly available documents as well as information provided by experts. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord TABLE OF CONTENTS List of abbreviations...................................................................................................................