Number 99 Caucasian Armenia Between Imperial A1\Id

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cabinet of Armenia, 1920

Cabinet of Armenia, 1920 MUNUC 32 TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________ Letter from the Crisis Director…………………………………………………3 Letter from the Chair………………………………………….………………..4 The History of Armenia…………………………………………………………6 The Geography of Armenia…………………………………………………14 Current Situation………………………………………………………………17 Character Biographies……………………………………………………....27 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………...37 2 Cabinet of Armenia, 1920 | MUNUC 32 LETTER FROM THE CRISIS DIRECTOR ______________________________________________________ Dear Delegates, We’re very happy to welcome you to MUNUC XXXII! My name is Andre Altherr and I’ll be your Crisis Director for the Cabinet of Armenia: 1920 committee. I’m from New York City and am currently a Second Year at the University of Chicago majoring in History and Political Science. Despite once having a social life, I now spend my free-time on much tamer activities like reading 800-page books on Armenian history, reading 900-page books on Central European history, and relaxing with the best of Stephen King and 20th century sci-fi anthologies. When not reading, I enjoy hiking, watching Frasier, and trying to catch up on much needed sleep. I’ve helped run and participated in numerous Model UN conferences in both college and high school, and I believe that this activity has the potential to hone public speaking, develop your creativity and critical thinking, and ignite interest in new fields. Devin and I care very deeply about making this committee an inclusive space in which all of you feel safe, comfortable, and motivated to challenge yourself to grow as a delegate, statesperson, and human. We trust that you will conduct yourselves with maturity and tact when discussing sensitive subjects. -

REVOLUTION GOES EAST Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University

REVOLUTION GOES EAST Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University The Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute of Columbia University were inaugu rated in 1962 to bring to a wider public the results of significant new research on modern and contemporary East Asia. REVOLUTION GOES EAST Imperial Japan and Soviet Communism Tatiana Linkhoeva CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON This book is freely available in an open access edition thanks to TOME (Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem)—a collaboration of the Association of American Universities, the Association of University Presses, and the Association of Research Libraries—and the generous support of New York University. Learn more at the TOME website, which can be found at the following web address: openmono graphs.org. The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International: https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0. To use this book, or parts of this book, in any way not covered by the license, please contact Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress. cornell.edu. Copyright © 2020 by Cornell University First published 2020 by Cornell University Press Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Linkhoeva, Tatiana, 1979– author. Title: Revolution goes east : imperial Japan and Soviet communism / Tatiana Linkhoeva. Description: Ithaca [New York] : Cornell University Press, 2020. | Series: Studies of the Weatherhead East Asian Institute, Columbia University | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2019020874 (print) | LCCN 2019980700 (ebook) | ISBN 9781501748080 (pbk) | ISBN 9781501748097 (epub) | ISBN 9781501748103 (pdf) Subjects: LCSH: Communism—Japan—History—20th century. -

Pacifism and Apocalyptic Discourse Among Russian Spiritual Christian Molokan-Jumpers

Church History 80:1 (March 2011), 109–138. © American Society of Church History, 2011 doi:10.1017/S0009640710001587 The Woman Clothed in the Sun: Pacifism and Apocalyptic Discourse among Russian Spiritual Christian Molokan-Jumpers J. EUGENE CLAY ITH its violent images of heavenly and earthly combat, the book of Revelation has been criticized for promoting a vengeful and Wdistorted version of Christ’s teachings. Gerd Lüdemann, for example, has attacked the book as part of the “dark side of the Bible,” and Jonathan Kirsch believes that the pernicious influence of Revelation “can be detected in some of the worst atrocities and excesses of every age, including our own.”1 Yet, surprisingly, nonviolent pacifists have also drawn on the Apocalypse for encouragement and support. This was especially true for generations of Russian Spiritual Christians (dukhovnye khristiane), a significant religious minority whose roots trace at least as far back as the 1760s, when the first “spirituals” (dukhovnye) were arrested and tried in Russia’s southern provinces of Tambov and Voronezh. Although they drew upon apocalyptic martial imagery, the Spiritual Christians were pacifists, some of whom came to identify themselves with the Woman Clothed in the Sun of Revelation 12. Spiritual Christians refused to recognize the sacraments, clergy, and icons of the state church; rather than kiss and bow to icons, they kissed and bowed to one another, and thus venerated human beings, who were the true image—or Research for this article was supported by the Pew Evangelical Scholars Initiative, by seed grants from the Institute for Humanities Research and the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict at Arizona State University, and by the International Research and Exchanges Board with funds provided by the U.S. -

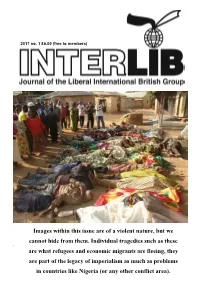

Images Within This Issue Are of a Violent Nature, but We Cannot Hide from Them

2017 no. 1 £6.00 (free to members) Images within this issue are of a violent nature, but we cannot hide from them. Individual tragedies such as these . are what refugees and economic migrants are fleeing, they are part of the legacy of imperialism as much as problems in countries like Nigeria (or any other conflict area). EVENTS CONTENTS 30th January 2017 Isaiah Berlin Lecture. 1.00pm Nigeria and the legacy of military rule. Chatham House by Rebecca Tinsley Pages 3-5 9th February 2017 Chinese New Year Dinner and Auction. Guest Speaker: Prof Kerry Brown. £45. Indonesia, the sleeping giant awakes. 7.00pm NLC. RSVP [email protected] by Howard Henshaw Pages 7-8 18-19th February 2017 Cymdeithas Lloyd George – Lloyd George Society Weekend School. Hotel Com- Some culture and politics of Georgia. modore, Llandrindod Wells. by Kiron Reid Pages 9-11 https://lloydgeorgesociety.org.uk 20th February 2017 LIBG Forum on French elec- International Abstracts Pages 12-13 tions, co-hosted with MoDem. NLC European Parliament Brexit Chief to deliver 4th March 2017 Rights Liberty Justice Pop-Up Con- 2017 Isaiah Berlin Lecture in London Page 13 ference – The Supreme Court Article 50 decision & beyond. Bermondsey Village Hall, near London Reviews Pages 14-16 Bridge Station 6th March 2017 LIBG Executive, NLC 13th March 2017 LIBG Forum on the South China Photographs: Anon, Howard Henshaw, Kiron Reid. Sea. NLC 17th-19th March 2017 Liberal Democrat Spring Con- ference, York. 25th March 2017 Unite For Europe National March to Parliament. 11.00am London 15th May 2017 LIBG Forum on East Africa. -

Spotlight on Azerbaijan

Spotlight on azerbaijan provides an in-depth but accessible analysis of the major challenges Azerbaijan faces regarding democratic development, rule of law, media freedom, property rights and a number of other key governance and human rights issues while examining the impact of its international relationships, the economy and the unresolved nagorno-Karabakh conflict on the domestic situation. it argues that UK, EU and Western engagement in Azerbaijan needs to go beyond energy diplomacy but that increased engagement must be matched by stronger pressure for reform. Edited by Adam hug (Foreign policy Centre) Spotlight on Azerbaijan contains contributions from leading Azerbaijan experts including: Vugar Bayramov (Centre for Economic and Social Development), Michelle Brady (American Bar Association Rule of law initiative), giorgi gogia (human Rights Watch), Vugar gojayev (human Rights house-Azerbaijan) , Jacqueline hale (oSi-EU), Rashid hajili (Media Rights institute), tabib huseynov, Monica Martinez (oSCE), Dr Katy pearce (University of Washington), Firdevs Robinson (FpC) and Denis Sammut (linKS). The Foreign Policy Centre Spotlight on Suite 11, Second floor 23-28 Penn Street London N1 5DL United Kingdom www.fpc.org.uk [email protected] aZERBaIJaN © Foreign Policy Centre 2011 Edited by adam Hug all rights reserved ISBN-13 978-1-905833-24-5 ISBN-10 1-905833-24-5 £4.95 Spotlight on Azerbaijan Edited by Adam Hug First published in May 2012 by The Foreign Policy Centre Suite 11, Second Floor, 23-28 Penn Street London N1 5DL www.fpc.org.uk [email protected] © Foreign Policy Centre 2012 All Rights Reserved ISBN 13: 978-1-905833-24-5 ISBN 10: 1-905833-24-5 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foreign Policy Centre. -

Javakheti After the Rose Revolution: Progress and Regress in the Pursuit of National Unity in Georgia

Javakheti after the Rose Revolution: Progress and Regress in the Pursuit of National Unity in Georgia Hedvig Lohm ECMI Working Paper #38 April 2007 EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR MINORITY ISSUES (ECMI) ECMI Headquarters: Schiffbruecke 12 (Kompagnietor) D-24939 Flensburg Germany +49-(0)461-14 14 9-0 fax +49-(0)461-14 14 9-19 Internet: http://www.ecmi.de ECMI Working Paper #38 European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) Director: Dr. Marc Weller Copyright 2007 European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) Published in April 2007 by the European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) ISSN: 1435-9812 2 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................4 II. JAVAKHETI IN SOCIO-ECONOMIC TERMS ...........................................................5 1. The Current Socio-Economic Situation .............................................................................6 2. Transformation of Agriculture ...........................................................................................8 3. Socio-Economic Dependency on Russia .......................................................................... 10 III. DIFFERENT ACTORS IN JAVAKHETI ................................................................... 12 1. Tbilisi influence on Javakheti .......................................................................................... 12 2. Role of Armenia and Russia ............................................................................................. 13 3. International -

Armenia, Republic of | Grove

Grove Art Online Armenia, Republic of [Hayasdan; Hayq; anc. Pers. Armina] Lucy Der Manuelian, Armen Zarian, Vrej Nersessian, Nonna S. Stepanyan, Murray L. Eiland and Dickran Kouymjian https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T004089 Published online: 2003 updated bibliography, 26 May 2010 Country in the southern part of the Transcaucasian region; its capital is Erevan. Present-day Armenia is bounded by Georgia to the north, Iran to the south-east, Azerbaijan to the east and Turkey to the west. From 1920 to 1991 Armenia was a Soviet Socialist Republic within the USSR, but historically its land encompassed a much greater area including parts of all present-day bordering countries (see fig.). At its greatest extent it occupied the plateau covering most of what is now central and eastern Turkey (c. 300,000 sq. km) bounded on the north by the Pontic Range and on the south by the Taurus and Kurdistan mountains. During the 11th century another Armenian state was formed to the west of Historic Armenia on the Cilician plain in south-east Asia Minor, bounded by the Taurus Mountains on the west and the Amanus (Nur) Mountains on the east. Its strategic location between East and West made Historic or Greater Armenia an important country to control, and for centuries it was a battlefield in the struggle for power between surrounding empires. Periods of domination and division have alternated with centuries of independence, during which the country was divided into one or more kingdoms. Page 1 of 47 PRINTED FROM Oxford Art Online. © Oxford University Press, 2019. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 i v ABSTRACT Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Yektan Turkyilmaz 2011 Abstract This dissertation examines the conflict in Eastern Anatolia in the early 20th century and the memory politics around it. It shows how discourses of victimhood have been engines of grievance that power the politics of fear, hatred and competing, exclusionary -

Ser Oliver Uordropi 150

saqarTvelos parlamentis erovnuli biblioTeka saqarTvelos erovnuli arqivi ser oliver uordropi 150 Tbilisi 2015 1 UDC (uak) 001 (410)(092) 008.1 (479.22.410) wigni Seadgina, SeniSvnebi da komentarebi daurTo, redaqtireba gaukeTa, inglisuri teqsti qarTul Targmans Seudara istoriis doqtorma: beqa kobaxiZem teqsti inglisuridan qarTul enaze Targmna: salome beniZem qarTuli Targmanis stilisturi redaqtireba diana anfimiadisa wina ydaze gamosaxulia saqarTvelos sagareo saqmeTa ministri - evgeni gegeWkori da didi britaneTis umaRlesi komisari - ser oliver uordropi tfilisSi 1919 wlis 30 agvistos mowyobil daxvedraze. foto daculia saqarTvelos erovnul arqivSi. On the front cover there are illustrated Minister of Foreign Affairs of Georgia – Evgeni Gegechkori and British High Commissioner in Transcaucasia – Sir Oliver Wardrop at the arrival meeting of Wardrop in Tiflis on 30th of August 1919. The photograph is preserved in the National Archives of Georgia. ukana ydaze gamosaxulia ser oliver uordropi - misi udidebulesobis generaluri konsuli strasburgSi. 1925 weli. foto hilari grandis uordropebis ojaxis albomidan. On the back cover there is illustrated Sir Oliver Wardrop – His Majesty’s Consul-General in Strasbourg. 1925. Photograph from Wardrops family album of Hilary Grundy. © saqarTvelos parlamentis erovnuli biblioTeka © saqarTvelos erovnuli arqivi Sps “irida” rusTavi, firosmanis q.#7 ISBN 978-9941-0-8216-0 2 sarCevi: redaqtoris winasityvaoba ...............................................................................................4 “ser oliver uordropi: -

The Bolshevil{S and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds

The Bolshevil{s and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds Chinese Worlds publishes high-quality scholarship, research monographs, and source collections on Chinese history and society from 1900 into the next century. "Worlds" signals the ethnic, cultural, and political multiformity and regional diversity of China, the cycles of unity and division through which China's modern history has passed, and recent research trends toward regional studies and local issues. It also signals that Chineseness is not contained within territorial borders overseas Chinese communities in all countries and regions are also "Chinese worlds". The editors see them as part of a political, economic, social, and cultural continuum that spans the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, South East Asia, and the world. The focus of Chinese Worlds is on modern politics and society and history. It includes both history in its broader sweep and specialist monographs on Chinese politics, anthropology, political economy, sociology, education, and the social science aspects of culture and religions. The Literary Field of New Fourth Artny Twentieth-Century China Communist Resistance along the Edited by Michel Hockx Yangtze and the Huai, 1938-1941 Gregor Benton Chinese Business in Malaysia Accumulation, Ascendance, A Road is Made Accommodation Communism in Shanghai 1920-1927 Edmund Terence Gomez Steve Smith Internal and International Migration The Bolsheviks and the Chinese Chinese Perspectives Revolution 1919-1927 Edited by Frank N Pieke and Hein Mallee -

English Selection 2018

ISSN 2409-2274 NATIONAL RESEARCH UNIVERSITY HIGHER SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS ENGLISH SELECTION 2018 CONTENTS HERBERT SPENCER: THE UNRECOGNIZED FATHER OF THE THEORY OF DEMOGRAPHIC TRANSITION ANATOLY VISHNEVSKY RETHINKING THE CONTEMPORARY HISTORY OF FERTILITY: FAMILY, STATE, AND THE WORLD SYSTEM MIKHAIL KLUPT GENERATIONAL ACCOUNTS AND DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND IN RUSSIA MIKHAIL DENISENKO, VLADIMIR KOZLOV CITIES OF OVER A MILLION PEOPLE ON THE MORTALITY MAP OF RUSSIA ALEKSEI SHCHUR ARMENIANS OF RUSSIA: GEO-DEMOGRAPHIC TRENDS OF THE PAST, MODERN REALITIES AND PROSPECTS SERGEI SUSHCHIY AN EVALUATION OF THE PREVALENCE OF MALIGNANT NEOPLASMS IN RUSSIA USING INCIDENCE-MORTALITY MODEL RUSTAM TURSUN-ZADE • DEMOGRAPHIC REVIEW • EDITORIAL BOARD: INTERNATIONAL EDITORIAL COUNCIL: E. ANDREEV V. MUKOMEL B. ANDERSON (USA) T. MALEVA M. DENISSENKO L. OVCHAROVA O. GAGAUZ (Moldova) F. MESLÉ (France) V. ELIZAROV P. POLIAN I. ELISEEVA B. MIRONOV S. IVANOV A. PYANKOVA Z. ZAYONCHKOVSKAYA S. NIKITINA A. IVANOVA M. SAVOSKUL N. ZUBAREVICH Z. PAVLIK (Czech Republic) I. KALABIKHINA S. TIMONIN V. IONTSEV V. STANKUNIENE (Lithuania) M. KLUPT A. TREIVISCH E. LIBANOVA (Ukraine) M. TOLTS (Israel) A. MIKHEYEVA A. VISHNEVSKY M. LIVI BACCI (Italy) V. SHKOLNIKOV (Germany) N. MKRTCHYAN V. VLASOV T. MAKSIMOVA S. SCHERBOV (Austria) S. ZAKHAROV EDITORIAL OFFICE: Editor-in-Chief - Anatoly G. VISHNEVSKY Deputy Editor-in-Chief - Sergey A. TIMONIN Deputy Editor-in-Chief - Nikita V. MKRTCHYAN Managing Editor – Anastasia I. PYANKOVA Proofreader - Natalia S. ZHULEVA Design and Making-up - Kirill V. RESHETNIKOV English translation – Christopher SCHMICH The journal is registered on October 13, 2016 in the Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology, and Mass Media. Certificate of Mass Media Registration ЭЛ № ФС77-67362.