Spotlight on Azerbaijan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nationwide March to Commemorate 27Th Anniversary of Khojaly

A nationwide march has been held in Baku to commemorate the 27th anniversary of Khojaly genocide, one of the bloodiest crimes in the history of mankind. President of the Republic of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev, first lady Mehriban Aliyeva and family members attended the march. TheThe nationwide nationwide march, march, which which began began from from the the Azadlyg Azadlyg Square Square in inKhatai Khatai district, district, involves involves ten ten thousands thousands of of people.people. They They gathered gathered to to pay pay tribute tribute to to victims victims of of Khojaly Khojaly tragedy tragedy and and draw draw the the world world community`s community`s attention attention to to this this crime against humanity, which was committed by the Armenian fascists. WithWith President President Ilham Ilham Aliyev Aliyev and and first first lady lady Mehriban Mehriban Aliyeva Aliyeva in in the the front front row, row, the the marchers marchers started started moving moving in in thethe directiondirection ofof thethe KhojalyKhojaly memorialmemorial inin KhataiKhatai district.district. Thousands of young people gathered along the avenues and streets that the marchers are moving. They hold portraitsportraits of innocent of innocent victims victims of the of bloodythe bloody event event – slaughtered – slaughtered children, children, women women and andelders elders – photos – photos depicting depicting abominableabominable scenesscenes ofof slaughter,slaughter, placardsplacards demandingdemanding toto bringbring toto accountaccount andand -

Azerbaijan: the Burden of History – Waiting for Change

2 Azerbaijan: The burden of history – waiting for change Arif Yunusov Young recruit guarding parliament in Baku PHOTO: ANNA MATVEEVA Summary Azerbaijan was not traditionally a nation with a strong ‘gun culture.’When conflict flared up in 1988 over Nagorno Karabakh, a largely Armenian-populated autonomous region which was demanding freedom from Azerbaijan, most people were unarmed. This paper traces the methods by which Azeris went about acquiring arms. This began on a small scale, as local paramilitary groups obtained weapons from wherever they could, in particular from Soviet military stores. As the conflict grew, however, both sides started to acquire larger quantities of SALW and heavy weaponry. When Azerbaijan became an independent state in October 1991, arms acquisition became a matter for the newly- founded armed forces. The country obtained a large quantity of arms through the division of Soviet military property in the South Caucasus, and further weapons were obtained through illicit purchases and seizures of Soviet weapons. Yet because of internal political disputes, Azerbaijan remained military weak, crime in the republic rose, and the country remained deeply unstable until Heydar Aliev came to power in 1993. Since a ceasefire was agreed in Nagorno Karabakh in 1994, the situation has stabilised and the state has largely succeeded in stemming SALW proliferation. The paper finishes by considering the current condition of the military and security sectors and recent political developments. 2 THE CAUCASUS: ARMED AND DIVIDED · AZERBAIJAN Small Arms and Until the start of the Nagorno Karabakh conflict in 1988 and the fall of the USSR in Light Weapons 1991 Azerbaijani attitudes towards the use of small arms and light weapons (SALW) in Soviet were closely linked to its people’s history and mentality. -

Azerbaijan Azerbaijan

COUNTRY REPORT ON THE STATE OF PLANT GENETIC RESOURCES FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE AZERBAIJAN AZERBAIJAN National Report on the State of Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture in Azerbaijan Baku – December 2006 2 Note by FAO This Country Report has been prepared by the national authorities in the context of the preparatory process for the Second Report on the State of World’s Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. The Report is being made available by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) as requested by the Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. However, the report is solely the responsibility of the national authorities. The information in this report has not been verified by FAO, and the opinions expressed do not necessarily represent the views or policy of FAO. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of FAO concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAO. CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 7 INTRODUCTION 8 1. -

Images Within This Issue Are of a Violent Nature, but We Cannot Hide from Them

2017 no. 1 £6.00 (free to members) Images within this issue are of a violent nature, but we cannot hide from them. Individual tragedies such as these . are what refugees and economic migrants are fleeing, they are part of the legacy of imperialism as much as problems in countries like Nigeria (or any other conflict area). EVENTS CONTENTS 30th January 2017 Isaiah Berlin Lecture. 1.00pm Nigeria and the legacy of military rule. Chatham House by Rebecca Tinsley Pages 3-5 9th February 2017 Chinese New Year Dinner and Auction. Guest Speaker: Prof Kerry Brown. £45. Indonesia, the sleeping giant awakes. 7.00pm NLC. RSVP [email protected] by Howard Henshaw Pages 7-8 18-19th February 2017 Cymdeithas Lloyd George – Lloyd George Society Weekend School. Hotel Com- Some culture and politics of Georgia. modore, Llandrindod Wells. by Kiron Reid Pages 9-11 https://lloydgeorgesociety.org.uk 20th February 2017 LIBG Forum on French elec- International Abstracts Pages 12-13 tions, co-hosted with MoDem. NLC European Parliament Brexit Chief to deliver 4th March 2017 Rights Liberty Justice Pop-Up Con- 2017 Isaiah Berlin Lecture in London Page 13 ference – The Supreme Court Article 50 decision & beyond. Bermondsey Village Hall, near London Reviews Pages 14-16 Bridge Station 6th March 2017 LIBG Executive, NLC 13th March 2017 LIBG Forum on the South China Photographs: Anon, Howard Henshaw, Kiron Reid. Sea. NLC 17th-19th March 2017 Liberal Democrat Spring Con- ference, York. 25th March 2017 Unite For Europe National March to Parliament. 11.00am London 15th May 2017 LIBG Forum on East Africa. -

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

EU Relations with Armenia and Azerbaijan.Pdf

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR EXTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS EU relations with Armenia and Azerbaijan ABSTRACT The EU is currently reshaping its relationship with Armenia and Azerbaijan through new agreements for which the negotiations ended (Armenia) or started (Azerbaijan) in February 2017. After Yerevan’s decision to join the EAEU (thereby renouncing to sign an AA/DCFTA), the initialling of the CEPA provides a new impetus to EU-Armenia relations. It highlights Armenia’s lingering interest in developing closer ties with the EU and provides a vivid illustration of the EU’s readiness to respond to EaP countries’ specific needs and circumstances. The CEPA is also a clear indication that the EU has not engaged in a zero- sum game with Russia and is willing to exploit any opportunity to further its links with EaP countries. The launch of negotiations on a new EU-Azerbaijan agreement – in spite of serious political and human rights problems in the country – results from several intertwined factors, including the EU’s energy security needs and Baku’s increasing bargaining power. At this stage, Azerbaijan is interested only in forms of cooperation that are not challenging the political status quo. However, the decline in both world oil prices and domestic oil production in this country is creating bargaining opportunities for the EU in what promises to be a difficult negotiation. EP/EXPO/B/AFET/FWC/2013-08/Lot6/15 EN October 2017 - PE 603.846 © European Union, 2017 Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies This paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Foreign Affairs. -

Of Iraq's Kirkuk

INSTITUT KURDDE PARIS E Information and liaison bulletin N° 392 NOVEMBER 2017 The publication of this Bulletin enjoys a subsidy from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Ministry of Culture This bulletin is issued in French and English Price per issue : France: 6 € — Abroad : 7,5 € Annual subscribtion (12 issues) France : 60 € — Elsewhere : 75 € Monthly review Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN Misen en page et maquette : Ṣerefettin ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tel. : 01-48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01-48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: bulletin@fikp.org Information and liaison bulletin Kurdish Institute of Paris Bulletin N° 392 November 2017 • ROJAVA: PREPARING MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE • TURKEY: THE REPRESSION EXPANDS TO LIBER- AL CIRCLES; THE VIOLENCE IS INCREASING • IRAQI KURDISTAN: UNCONSTITUTIONAL DEMANDS FROM BAGHDAD, ARABISATION OF KIRKUK RESTARTED ROJAVA: PREPARING MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS IN THE CONTEXT OF AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE. broad the “World Day for beginning to return to Raqqa, liber- the 17th with a suicide attack on a Kobani” was celebrated ated on 17th October. Regarding checkpoint that caused at least 35 on 1st November largely Deir Ezzor, the SDF fighters from victims in the Northeast of Deir as a symbol of this Syrian the “Jezirah Storm” operation, Ezzor Province, between the hydro- A Kurdish town’s unremit- launched on 9th September, liberated carbon fields of Conoco and Jafra. It ting resistance to the attack 7 villages near the town and about was, nevertheless, not able to pre- launched by ISIS in 2014 with fifteen km from the Iraqi borders, vent the SDF from reaching the Iraqi Turkish connivance. -

Azerbaijan | Freedom House

Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan About Us DONATE Blog Mobile App Contact Us Mexico Website (in Spanish) REGIONS ISSUES Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Subscribe Donate NATIONS IN TRANSIT - View another year - ShareShareShareShareShareMore 7 Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Nations in Transit 2014 DRAFT REPORT 2014 SCORES PDF version Capital: Baku 6.68 Population: 9.3 million REGIME CLASSIFICATION GNI/capita, PPP: US$9,410 Consolidated Source: The data above are drawn from The World Bank, Authoritarian World Development Indicators 2014. Regime 6.75 7.00 6.50 6.75 6.50 6.50 6.75 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. The Democracy Score is an average of ratings for the categories tracked in a given year. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: 1 of 23 6/25/2014 11:26 AM Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan Azerbaijan is ruled by an authoritarian regime characterized by intolerance for dissent and disregard for civil liberties and political rights. When President Heydar Aliyev came to power in 1993, he secured a ceasefire in Azerbaijan’s war with Armenia and established relative domestic stability, but he also instituted a Soviet-style, vertical power system, based on patronage and the suppression of political dissent. Ilham Aliyev succeeded his father in 2003, continuing and intensifying the most repressive aspects of his father’s rule. -

Ser Oliver Uordropi 150

saqarTvelos parlamentis erovnuli biblioTeka saqarTvelos erovnuli arqivi ser oliver uordropi 150 Tbilisi 2015 1 UDC (uak) 001 (410)(092) 008.1 (479.22.410) wigni Seadgina, SeniSvnebi da komentarebi daurTo, redaqtireba gaukeTa, inglisuri teqsti qarTul Targmans Seudara istoriis doqtorma: beqa kobaxiZem teqsti inglisuridan qarTul enaze Targmna: salome beniZem qarTuli Targmanis stilisturi redaqtireba diana anfimiadisa wina ydaze gamosaxulia saqarTvelos sagareo saqmeTa ministri - evgeni gegeWkori da didi britaneTis umaRlesi komisari - ser oliver uordropi tfilisSi 1919 wlis 30 agvistos mowyobil daxvedraze. foto daculia saqarTvelos erovnul arqivSi. On the front cover there are illustrated Minister of Foreign Affairs of Georgia – Evgeni Gegechkori and British High Commissioner in Transcaucasia – Sir Oliver Wardrop at the arrival meeting of Wardrop in Tiflis on 30th of August 1919. The photograph is preserved in the National Archives of Georgia. ukana ydaze gamosaxulia ser oliver uordropi - misi udidebulesobis generaluri konsuli strasburgSi. 1925 weli. foto hilari grandis uordropebis ojaxis albomidan. On the back cover there is illustrated Sir Oliver Wardrop – His Majesty’s Consul-General in Strasbourg. 1925. Photograph from Wardrops family album of Hilary Grundy. © saqarTvelos parlamentis erovnuli biblioTeka © saqarTvelos erovnuli arqivi Sps “irida” rusTavi, firosmanis q.#7 ISBN 978-9941-0-8216-0 2 sarCevi: redaqtoris winasityvaoba ...............................................................................................4 “ser oliver uordropi: -

Combatting and Preventing Corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia How Anti-Corruption Measures Can Promote Democracy and the Rule of Law

Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia How anti-corruption measures can promote democracy and the rule of law Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia How anti-corruption measures can promote democracy and the rule of law Silvia Stöber Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia 4 Contents Contents 1. Instead of a preface: Why (read) this study? 9 2. Introduction 11 2.1 Methodology 11 2.2 Corruption 11 2.2.1 Consequences of corruption 12 2.2.2 Forms of corruption 13 2.3 Combatting corruption 13 2.4 References 14 3. Executive Summaries 15 3.1 Armenia – A promising change of power 15 3.2 Azerbaijan – Retaining power and preventing petty corruption 16 3.3 Georgia – An anti-corruption role model with dents 18 4. Armenia 22 4.1 Introduction to the current situation 22 4.2 Historical background 24 4.2.1 Consolidation of the oligarchic system 25 4.2.2 Lack of trust in the government 25 4.3 The Pashinyan government’s anti-corruption measures 27 4.3.1 Background conditions 27 4.3.2 Measures to combat grand corruption 28 4.3.3 Judiciary 30 4.3.4 Monopoly structures in the economy 31 4.4 Petty corruption 33 4.4.1 Higher education 33 4.4.2 Health-care sector 34 4.4.3 Law enforcement 35 4.5 International implications 36 4.5.1 Organized crime and money laundering 36 4.5.2 Migration and asylum 36 4.6 References 37 5 Combatting and preventing corruption in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia 5. -

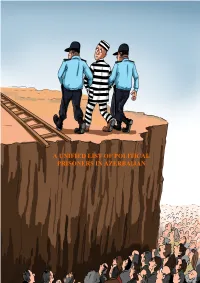

A Unified List of Political Prisoners in Azerbaijan

A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN A UNIFIED LIST OF POLITICAL PRISONERS IN AZERBAIJAN Covering the period up to 25 May 2017 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................4 DEFINITION OF POLITICAL PRISONERS...............................................................5 POLITICAL PRISONERS.....................................................................................6-106 A. Journalists/Bloggers......................................................................................6-14 B. Writers/Poets…...........................................................................................15-17 C. Human Rights Defenders............................................................................17-18 D. Political and social Activists ………..........................................................18-31 E. Religious Activists......................................................................................31-79 (1) Members of Muslim Unity Movement and those arrested in Nardaran Settlement...........................................................................31-60 (2) Persons detained in connection with the “Freedom for Hijab” protest held on 5 October 2012.........................60-63 (3) Religious Activists arrested in Masalli in 2012...............................63-65 (4) Religious Activists arrested in May 2012........................................65-69 (5) Chairman of Islamic Party of Azerbaijan and persons arrested -

£AZERBAIJAN @Allegations of Ill-Treatment in Detention

£AZERBAIJAN @Allegations of ill-treatment in detention Introduction Amnesty International continues to receive allegations of ill-treatment of detainees by Azerbaijani law enforcement officials. In some cases it has been alleged that prisoners have been beaten in pre-trial detention in order to obtain confessions, and that family members of suspects in hiding have been beaten in an attempt to obtain information on their relatives’ whereabouts. In other cases it has been alleged that prisoners in ill-health have not received adequate medical treatment, and that at least two people died as a result of this over the last year. General conditions for many in pre-trial detention are also reported to be harsh, with overcrowding so severe in some prisons that inmates are forced to take it in turns to sleep while others in the cell stand. Restricted access by independent observers makes verification of these allegations difficult, and Amnesty International has had no response to its concerns about ill-treatment which have been raised on a number of occasions with the Azerbaijani authorities. Cases illustrating Amnesty International’s concerns are detailed below. They relate to political prisoners1, although Amnesty International is also concerned about other more general allegations about ill-treatment of criminal prisoners. Deaths in custody Shahmardan Mahammad oglu Jafarov Shahmardan (also known as Shahsultan ) Jafarov died in custody in the Azerbaijani capital of Baku during the night of 29 to 30 June 1995. A parliamentarian and a member of the opposition Popular Front of Azerbaijan (PFA), he had sustained serious gunshot wounds in a clash with police on 17 June 1995 near the village of Abragunis in the Julfa district of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic (NAR).