Azerbaijan: Downward Spiral: Continuing Crackdown on Freedoms in Azerbaijan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TIGHTENING the SCREWS Azerbaijan’S Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS TIGHTENING THE SCREWS Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0473 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0473 Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Arrest and Imprisonment ......................................................................................................... -

6702-6734. (Mondale at 6726)

UNITED STATES OF Al\fERICA (LongrrssionallItfcord th PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 94 CONGRESS SECOND SESSION VOLU~IE 122-PART 6 11,\RGH IS, 1976 TO ~L\RC:f[ 2~;, 1'176 (PAGES 6397 TO 77G6' UNITED STATES GOVE~NM.ENT PRINTING OHICf, \VASHINGTO:.:'-l, 1976 6702 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD ~ SENATE lJtJarck 16,>19,'6 ping the FEC of its power and its in called to order by the Presiding Officer discloses any information about any pending dependence. I want no part in giving one (Mr. STAFFORD). case without the consent of the candidate involved. MeanwhUe the candidate would be interest group an unfair advantage over free to say anything he likes about the case another interest group. I want no part in or the FEC. Surely some less heavy-handed an effort to make this measure an in FEDERAL ELECTION CAMPAIGN ACT and more even-handed way can be found to cumbent's bill. S. 3065 would accomplish AMENDMENTS OF 1976 enforce discipline and inspire some sense of these things. I urge my colleagues to vote The Senate continued with the con responsibility on the part of FEC officials. against it and vote in favor of the simple sideration of the bill (S.3065) to amend From there, the bills go rapidly downhlll. reconstitution of the Commission. How Congressional InfiuenCe over the commis the Federal Election Campaign Act of sion would be intensified. Public dlsclosure ever, if the Senate shoUld adopt S. 3065 1971 to provide for its administration by of campaign finances In candidates' home as reported out of the Committee on a Federal Election Commission appointed states would be curtalled. -

Predators 2021 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 PREDATORS 2021 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Azerbaijan 167/180* Eritrea 180/180* Isaias AFWERKI Ilham Aliyev Born 2 February 1946 Born 24 December 1961 > President of the Republic of Eritrea > President of the Republic of Azerbaijan since 19 May 1993 since 2003 > Predator since 18 September 2001, the day he suddenly eliminated > Predator since taking office, but especially since 2014 his political rivals, closed all privately-owned media and jailed outspoken PREDATORY METHOD: Subservient judicial system journalists Azerbaijan’s subservient judicial system convicts journalists on absurd, spurious PREDATORY METHOD: Paranoid totalitarianism charges that are sometimes very serious, while the security services never The least attempt to question or challenge the regime is regarded as a threat to rush to investigate physical attacks on journalists and sometimes protect their “national security.” There are no more privately-owned media, only state media assailants, even when they have committed appalling crimes. Under President with Stalinist editorial policies. Journalists are regarded as enemies. Some have Aliyev, news sites can be legally blocked if they pose a “danger to the state died in prison, others have been imprisoned for the past 20 years in the most or society.” Censorship was stepped up during the war with neighbouring appalling conditions, without access to their family or a lawyer. According to Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh and the government routinely refuses to give the information RSF has been getting for the past two decades, journalists accreditation to foreign journalists. -

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Section 355 Reviews of Output: U105

Section 355 Reviews of Output: U105 When a local commercial radio licence undergoes a change of control (this includes licence transfer), Ofcom is required, under section 355 of the Communications Act 2003 (the Act), to undertake a review of the effects or likely effects of the change of control in relation to: • the quality and range of programmes included in the service; • the character of the service, and; • the extent to which Ofcom’s duty under section 314 of the Act is performed in relation to the service. Ofcom’s duty under section 314 of the Act relates to securing the inclusion of an appropriate amount of local material, and a suitable proportion of locally-made programmes in the service. Under section 356 of the Act, where it appears to Ofcom from its review that the change of control would be prejudicial to any of the three matters listed above, then it must vary the licence, by including such conditions as it considers appropriate, with a view to ensuring that the relevant change of control is not so prejudicial. In doing so, any new or varied conditions must be such that the licence holder would have satisfied them throughout the three months immediately before the change of control. Ofcom is required to publish a report of its review, setting out its conclusions and any steps it proposes to take under section 356. Where Ofcom proposes to vary the licence, it is required to give the licence holder a reasonable opportunity to make representations about the variation. On 23 November 2016, a change of control took place at the Wireless Group plc, as a result of all of the company’s share capital being acquired by News Corp UK & Ireland Limited. -

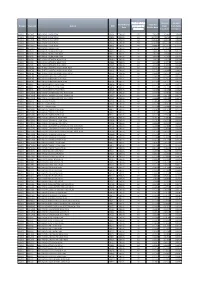

Domain Stationid Station UDC Performance Date

Number of days Amount Amount Performance Total Per Domain StationId Station UDC processed for from from Public Date Minute Rate distribution Broadcast Reception RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 NON PEAK BRA01 CENSUS 92 7.8347 4.2881 3.5466 RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 LOW PEAK BRB01 CENSUS 92 10.7078 7.1612 3.5466 RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 HIGH PEAK BRC01 CENSUS 92 13.5380 9.9913 3.5466 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 NON PEAK BRA02 CENSUS 92 17.4596 11.2373 6.2223 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 LOW PEAK BRB02 CENSUS 92 24.9887 18.7663 6.2223 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 HIGH PEAK BRC02 CENSUS 92 32.4053 26.1830 6.2223 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA NON PEAK BRA10 CENSUS 92 1.4814 1.4075 0.0739 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA LOW PEAK BRB10 CENSUS 92 2.4245 2.3506 0.0739 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA HIGH PEAK BRC10 CENSUS 92 3.3534 3.2795 0.0739 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK NON PEAK BRA65 CENSUS 92 1.4691 1.4593 0.0098 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK LOW PEAK BRB65 CENSUS 92 2.4468 2.4371 0.0098 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK HIGH PEAK BRC65 CENSUS 92 3.4100 3.4003 0.0098 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO NON PEAK BRA62 CENSUS 92 0.1516 0.1104 0.0411 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO LOW PEAK BRB62 CENSUS 92 0.2256 0.1844 0.0411 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO HIGH PEAK BRC62 CENSUS 92 0.2985 0.2573 0.0411 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE NON PEAK BRA64 CENSUS 92 0.0803 0.0569 0.0233 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE LOW PEAK BRB64 CENSUS 92 0.1184 0.0951 0.0233 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE HIGH PEAK BRC64 CENSUS 92 0.1560 0.1327 0.0233 RADIO BRBRIS BBC -

Spotlight on Azerbaijan

Spotlight on azerbaijan provides an in-depth but accessible analysis of the major challenges Azerbaijan faces regarding democratic development, rule of law, media freedom, property rights and a number of other key governance and human rights issues while examining the impact of its international relationships, the economy and the unresolved nagorno-Karabakh conflict on the domestic situation. it argues that UK, EU and Western engagement in Azerbaijan needs to go beyond energy diplomacy but that increased engagement must be matched by stronger pressure for reform. Edited by Adam hug (Foreign policy Centre) Spotlight on Azerbaijan contains contributions from leading Azerbaijan experts including: Vugar Bayramov (Centre for Economic and Social Development), Michelle Brady (American Bar Association Rule of law initiative), giorgi gogia (human Rights Watch), Vugar gojayev (human Rights house-Azerbaijan) , Jacqueline hale (oSi-EU), Rashid hajili (Media Rights institute), tabib huseynov, Monica Martinez (oSCE), Dr Katy pearce (University of Washington), Firdevs Robinson (FpC) and Denis Sammut (linKS). The Foreign Policy Centre Spotlight on Suite 11, Second floor 23-28 Penn Street London N1 5DL United Kingdom www.fpc.org.uk [email protected] aZERBaIJaN © Foreign Policy Centre 2011 Edited by adam Hug all rights reserved ISBN-13 978-1-905833-24-5 ISBN-10 1-905833-24-5 £4.95 Spotlight on Azerbaijan Edited by Adam Hug First published in May 2012 by The Foreign Policy Centre Suite 11, Second Floor, 23-28 Penn Street London N1 5DL www.fpc.org.uk [email protected] © Foreign Policy Centre 2012 All Rights Reserved ISBN 13: 978-1-905833-24-5 ISBN 10: 1-905833-24-5 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this report are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foreign Policy Centre. -

Freedom to Write Index 2019

FREEDOM TO WRITE INDEX 2019 Freedom to Write Index 2019 1 INTRODUCTION mid global retrenchment on human rights In 2019, countries in the Asia-Pacific region impris- Aand fundamental freedoms—deepening oned or detained 100 writers, or 42 percent of the authoritarianism in Russia, China, and much of the total number captured in the Index, while countries Middle East; democratic retreat in parts of Eastern in the Middle East and North Africa imprisoned or Europe, Latin America, and Asia; and new threats detained 73 writers, or 31 percent. Together these in established democracies in North America and two regions accounted for almost three-quarters Western Europe—the brave individuals who speak (73 percent) of the cases in the 2019 Index. Europe out, challenge tyranny, and make the intellectual and Central Asia was the third highest region, with case for freedom are on the front line of the battle 41 imprisoned/detained writers, or 17 percent of to keep societies open, defend the truth, and resist the 2019 Index; Turkey alone accounted for 30 of repression. Writers and intellectuals are often those cases. By contrast, incarceration of writers is among the canaries in the coal mine who, alongside relatively less prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, with journalists and human rights activists, are first 20 writers, or roughly eight percent of the count, and targeted when a country takes a more authoritarian the Americas, with four writers, just under two percent turn. The unjust detention and imprisonment of the count. The vast majority of imprisoned writers, of writers and intellectuals impacts both the intellectuals, and public commentators are men, but individuals themselves and the broader public, who women comprised 16 percent of all cases counted in are deprived of innovative and influential voices the 2019 Index. -

Installation Guidelines

THE NEW WAVE IN ROOFING IINSTALLATIONNSTALLATION GGUIDEUIDE Visit our website at: www.ondura.com Thank you for buying Ondura – the corrugated roofing and siding material that brings you both good looks and long life. Even though Ondura is easy to install, before begin- Ondura, like all roofing materials, should be carefully ning, you should thoroughly read these instructions to installed. Mistakes in installation can cause roof prob- understand how they apply to your roofing or siding job. lems later on. So take your time and closely follow We recommend you have an architect or structural these installation guidelines. As you can imagine, they engineer check your roofing plan for soundness and cannot cover all possible situations. especially for proper ventilation. Please use extreme caution on the roof to insure your personal safety at all times. Be sure that ladders and other such devices are safely posi- tioned and properly secured. OSHA recommends the use of a safety harness when applying roofing. Protective eyewear is recommended when applying fasteners or using power tools. When walking on Ondura, wear soft-soled shoes and place your feet perpendicular to the corrugations. All roofing is slippery when wet, dusty, frosty or oily...avoid working or walking on the roof if any of these conditions exist. Working on the roof if windy conditions exist can be dangerous and should be avoided. And, like any asphalt product, refrain from walk- ing on in high heat. Quick Estimating Guide For Sheets. Roofing Materials GETTING STARTED Sheet Dimensions = 48˝ W x 79˝ L • Sheets to cover a square, 4.5 (3.8 sheets equal 100 square feet or ice water shield are required. -

IV. Imprisonment and Harassment of Human Rights Defenders and Lawyers

HUMAN RIGHTS TIGHTENING THE SCREWS Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0473 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0473 Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Arrest and Imprisonment ......................................................................................................... -

Human Rights Abuses in Azerbaijan

1 1 Human Rights House Network The Human Rights House Network (HRHN) is a community of human rights defenders working for more than 100 independent organisations operating in 16 Human Rights Houses in 13 countries. Empowering, supporting, and protecting human rights defenders, the Network members unite their voices to promote the universal freedoms of assembly, organisation, and expression, and the right to be a human rights defender. The Secretariat, the Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF) based in Oslo, with offices in Geneva and Brussels, stewards the community, raising awareness internationally, raising concerns at the Council of Europe, the European Union and the United Nations, and other international institutions, and coordinating best use and sharing of the knowledge, expertise, influence, and resources within HRHN. Contact persons for the report: Alexander Sjödin European Advocacy Officer, Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF) Email: [email protected] Tel: +32 49 78 15 918 Florian Irminger Head of Advocacy, Human Rights House Foundation (HRHF) Email: [email protected] Tel: +41 79 751 80 42 Oslo office Menneskerettighetshuset Kirkegata 5, 0153 Oslo (Norway) Geneva office Rue de Varembé 1 (5th floor) PO Box 35, 1211 Geneva 20 (Switzerland) Brussels office Rue de Trèves 45, 1040 Brussels (Belgium) 2 For human rights defenders in Azerbaijan In June 2014, a number of Azerbaijani human rights defenders, including Emin Huseynov, Rasul Jafarov, and Intigam Aliyev organised a side-event in Strasbourg when President Aliyev addressed the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE). Two months later, Rasul Jafarov and Intigam Aliyev were arrested, and shortly thereafter Emin Huseynov fled to the Swiss Embassy in Baku for protection against his own impending arrest. -

Azerbaijan | Freedom House

Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan About Us DONATE Blog Mobile App Contact Us Mexico Website (in Spanish) REGIONS ISSUES Reports Programs Initiatives News Experts Events Subscribe Donate NATIONS IN TRANSIT - View another year - ShareShareShareShareShareMore 7 Azerbaijan Azerbaijan Nations in Transit 2014 DRAFT REPORT 2014 SCORES PDF version Capital: Baku 6.68 Population: 9.3 million REGIME CLASSIFICATION GNI/capita, PPP: US$9,410 Consolidated Source: The data above are drawn from The World Bank, Authoritarian World Development Indicators 2014. Regime 6.75 7.00 6.50 6.75 6.50 6.50 6.75 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the author(s). The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. The Democracy Score is an average of ratings for the categories tracked in a given year. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: 1 of 23 6/25/2014 11:26 AM Azerbaijan | Freedom House http://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2014/azerbaijan Azerbaijan is ruled by an authoritarian regime characterized by intolerance for dissent and disregard for civil liberties and political rights. When President Heydar Aliyev came to power in 1993, he secured a ceasefire in Azerbaijan’s war with Armenia and established relative domestic stability, but he also instituted a Soviet-style, vertical power system, based on patronage and the suppression of political dissent. Ilham Aliyev succeeded his father in 2003, continuing and intensifying the most repressive aspects of his father’s rule.