The Effect of the Project Method on the Development of Creative Thinking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NORD ANGLIA EDUCATION FAST FACTS Updated As of September 2019

NORD ANGLIA EDUCATION FAST FACTS Updated as of September 2019 About Nord Anglia Education Nord Anglia Education (NAE) is the world’s leading premium schools organisation, with campuses located across dozens of countries in the Americas, Europe, China, Southeast Asia, India and the Middle East. Together, our schools educate tens of thousands of students from kindergarten through to the end of secondary school. We are driven by one unifying philosophy: we are ambitious for our schools, students, teachers, staff and communities, and we inspire every child who attends an NAE school to achieve more than they ever imagined possible. Every parent wants the best for their child — so do we. NAE schools deliver high quality, transformational education and ensure excellent academic outcomes by going beyond traditional learning. Our global scale enables us to recruit and retain world-leading teachers and to offer unforgettable experiences through global and regional events, while our engaging learning environments ensure all of our students love coming to school. Founded in 1972 in the United Kingdom, the name Nord Anglia reflects the company’s beginnings in the north of England. NAE initially offered learning services such as English-as-a-foreign-language classes and grew during the 1980s by opening full-scale nurseries and kindergartens. In 1992, NAE opened its first international school, the British School of Warsaw. In the 2000s, the company began a strategic focus on premium international schools, with rapid growth in Asia, the Americas, China and across Europe and the Middle East. A truly international organisation, NAE now operates premium international schools worldwide. -

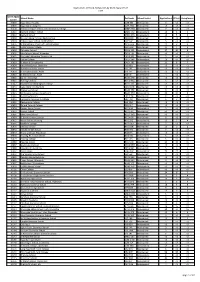

2017 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2017 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10006 Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni LL77 7NG Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 7 <3 <3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 13 6 5 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 5 5 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 4 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 5 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 11 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 17 4 3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 10 8 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent 5 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 <3 <3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 21 8 7 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent <3 <3 <3 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 4 <3 <3 10040 Garth Hill College RG42 2AD Maintained <3 <3 <3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 3 <3 <3 10042 Bracknell and Wokingham College RG12 1DJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained 3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU -

College of Nursing

Public Authority for Applied Education and Training College of Nursing 2020 FACULTY HANDBOOK APPROVED ON FEBRUARY 14, 2020 This paper is intentionally being left blank 1 CONTENTS The Public authority for applied educatino and training and college of nursing ........................................... 7 Vision .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Mission ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 College of nursing ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Vision .......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Mission ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 CoN core values .......................................................................................................................................... 8 Philosophy .................................................................................................................................................... 10 Objectives: The Public Authority for Applied Education and Training and the college of nursing ............... 11 Role specific -

BSME Annual Conference 2020 School Attendance List

BSME Annual Conference 2020 School Attendance List Ajman Academy UAE - Ajman Ajyal International School UAE - Abu Dhabi Al Ain Academy UAE - Al Ain Al Basma British School UAE - Abu Dhabi Al Mamoura Academy UAE - Abu Dhabi Al Muna Primary School UAE - Abu Dhabi Al Rabeeh Academy UAE - Abu Dhabi Al Rabeeh School UAE - Abu Dhabi Al Shohub School UAE - Abu Dhabi Al Yasmina School UAE - Abu Dhabi Amity International School UAE - Abu Dhabi Arcadia School UAE - Dubai Aspen Heights British School UAE - Abu Dhabi As Seeb International School Sultanate of Oman Belvedere British School, Abu Dhabi UAE - Abu Dhabi Belvedere International School UAE - Al Ain Brighton College Abu Dhabi UAE - Abu Dhabi Brighton College Al Ain UAE - Al Ain Brighton College Dubai UAE - Dubai British International School Al Khobar Kingdom of Saudi Arabia British International School Riyadh Kingdom of Saudi Arabia British Overseas School of Karachi Pakistan British School Muscat Sultanate of Oman British School of Bahrain Bahrain British School Salalah Sultanate of Oman Cambridge English School Hawally Kuwait Cambridge English School Mangaf Kuwait Capital School Dubai UAE - Dubai Compass International School Doha Qatar Cranleigh Abu Dhabi UAE - Abu Dhabi Deira International School UAE - Dubai Dhahran British Grammar School Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Doha British School Qatar Doha College Qatar 1 Dove Green Private School UAE - Dubai Dubai British Foundation UAE - Dubai Dubai English Speaking School/College UAE - Dubai Dubai Heights Academy UAE - Dubai Dubai Scholars Private -

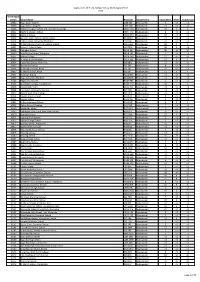

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2018 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 6 <3 <3 10006 Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni LL77 7NG Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 10 3 3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 8 <3 <3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 17 <3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 10 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 29 3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 30 10 10 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 5 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 11 <3 <3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 15 4 4 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent <3 <3 <3 10036 The Marist School SL5 7PS Independent 4 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 11 5 4 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained <3 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained 6 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 30 7 5 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10053 Oxford Sixth Form College OX1 4HT Independent <3 <3 -

P24 Layout 1

24 Established 1961 What’s On Tuesday, February 6, 2018 Landmark Group announces winners of ‘Art Olympiad X’ andmark Group awarded the artistic talents of eight students at event is seen as a grooming platform for these students by helping the tenth Art Olympiad held this year. The event saw the partici- them improvise their flair and encourage their innovative ability Lpation of 160 students from 16 schools of repute across Kuwait. through art. The atmosphere was abuzz with excitement as the names of winners Saibal Basu, Chief Operating Officer of Landmark Group Kuwait were announced. The Art Olympiad which recognizes the outstanding said, “My heartiest congratulations to the winners, I would also like to creative talents of students got an overwhelming response. acknowledge the efforts of the rest of the talented students who par- The paintings were judged by Walid Kanafani, President - IAA ticipated in this competition. Their talent is a reflection of their hard Kuwait Chapter and General Manager, Wavemaker Kuwait and Zeina work and artist vision which impress us with their outlook towards Mokaddam, Managing Director at PH7 Group. A total of eight winners things around them. Once again, we are proud and excited to hold the were selected at the end of the Olympiad on the basis of creativity, competition year after year and are continually amazed by the ability workmanship, overall impression and relevance to the Theme. The our young students have. Every year the Olympiad proves to be a paintings of the young talented artists offered the judges to choose great accomplishment; it only gets bigger and better.” the best of the best. -

GCC Education Industry | November 13, 2018 Page|1

GCC Education Industry | November 13, 2018 Page|1 Alpen Capital was awarded the “Best Research House” at the Banker Middle East Industry Awards 2011, 2013, and 2014 GCC Education Industry | November 13, 2018 Page|2 Table of Contents 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................ 9 1.1 Scope of the Report ..................................................................................... 9 1.2 Industry Outlook ......................................................................................... 9 1.3 Key Growth Drivers ..................................................................................... 10 1.4 Key Challenges .......................................................................................... 10 1.5 Key Trends ................................................................................................ 10 2. THE GCC EDUCATION INDUSTRY OVERVIEW ....................................... 11 2.1 The Saudi Arabian Education Sector .............................................................. 16 2.2 The UAE Education Sector ............................................................................ 20 2.3 The Omani Education Sector ........................................................................ 25 2.4 The Kuwaiti Education Sector ....................................................................... 29 2.5 The Qatari Education Sector ......................................................................... 32 2.6 The Bahraini Education Sector ..................................................................... -

NAE Principle Pack Generic Final 43 SCHOOLS Copy

You can achieve more with Nord Anglia Education 2 Information for Candidates — Head of Secondary 3 DearDear Candidatescandidate, candidate, Nord Anglia Education is the world’s leading premium schools organisation. We are Nord Anglia Education is the world’s leading premium schools organisation. We are ambitious for our students, our people and our family of schools. We are a fast paced ambitious for our students, our people and our family of schools. We are a fast paced - ted to providing our students with the best possible education. to providing our students with the best possible education. With over twenty years of experience operating international schools around the world,With over the Nordtwenty Anglia years Education of experience group operating of schools, international of which the schools British around Vietnamese the world, Internationalthe Nord Anglia School Education is a part, group currently of schools, educates of which more the than British 55,000 Vietnamese students from EarlyInternational Years to Year School 13 (K-12)is a part, and currently employs educates over 8,000 more people than globally. 55,000 students from early years to Year 13 (K-12) and employs over 8,500 people globally. The role of Head of Secondary is key to the future success of our school. We are looking forWe an are experienced, looking for andynamic experienced, and inspirational dynamic and Head inspirational of Primary Head to join of and Secondary drive its to join developmentand drive the and development ongoing success. and ongoing success of this school.The role of Head of Secondary is key to the future success of our school. -

Doing Business in Kuwait

Doing Business in Kuwait 2011 Doing Business in Kuwait Doing Business in Kuwait In the preparation of this guide, every effort has been made to offer current, correct and clearly expressed information. However, the information in the text is intended to afford general guidelines only. This publication is distributed with the understanding that Ernst & Young is not responsible for any actions taken on the basis of information in this publication, nor for any errors or omissions contained therein. Ernst & Young is not attempting through this book to render legal, accounting or tax advice. Readers are encouraged to consult with professional advisers for advice concerning specific matters before making any decision. The information in this publication should be used as a research tool only, and not in lieu of the tax professional's own research with respect to client matters. Ernst & Young firms provide public accounting, tax and management consulting services in the principal cities of the world. This book is one in a series of country profiles prepared for use by clients and professional staff. Additional copies may be obtained from Ernst & Young (Al Aiban, Al Osaimi & Partners) P. 0. Box 74 Safat 18-21 Floor, Baitak Tower 13001 Safat, Kuwait. Telephone: (965) 22452880 Facsimile: (965) 2456419 All Rights Reserved Doing Business in Kuwait 2 – Ernst & Young Preface Preface This book was prepared by Ernst & Young, Kuwait, a member firm of Ernst & Young. It was written to give the busy executive a quick overview of the investment climate, taxation, forms of business organisation, and business and accounting practices in Kuwait. -

Restructuring the Cultural Division

EmbassyEmbassy ofof KuwaitKuwait CulturalCultural DivisionDivision AACRAOAACRAO PresentationPresentation MarchMarch 2,2, 20072007 Slide 1 ServicesServices OfferedOffered byby thethe CulturalCultural OfficeOffice The Cultural Office provides a range of services to its scholars: Intensive English and Academic Placement Monitoring Academic Progress Disbursement of Scholarship funds to students Payment of tuition and fees to colleges and universities Issuance of travel benefit Resources and information on U.S. educational programs and training opportunities Insurance Coverage Slide 2 BreakdownBreakdown ofof (Active)(Active) StudentsStudents ApproximatelyApproximately 15631563 activeactive studentsstudents ApproximatelyApproximately 93%93% inin U.S.A.U.S.A. (41(41 states)states) 7%7% inin CanadaCanada 10911091 UndergraduateUndergraduate StudentsStudents 126126 GraduateGraduate StudentsStudents 141141 Ph.D.Ph.D. StudentsStudents 205205 OtherOther (Residencies,(Residencies, Internships,Internships, Fellowships)Fellowships) as of Spring 2007 Slide 3 BreakdownBreakdown byby SponsoringSponsoring AgenciesAgencies MinistryMinistry ofof HigherHigher EducationEducation 776776 CivilCivil ServiceService Commission:Commission: 236236 KuwaitKuwait University:University: 216216 KuwaitKuwait InvestmentInvestment AuthorityAuthority 33 KuwaitKuwait InstituteInstitute forfor ScientificScientific ResearchResearch 1212 PublicPublic Authority:Authority: 8787 SpecialSpecial Foundations:Foundations: 9797 PrivatePrivate StudentsStudents (no(no -

COBIS Student Achievement Awards 2019

COBIS Student Achievement Awards 2019 Congratulations to all COBIS students who received a COBIS Student Achievement Award in 2019. Each year, COBIS Schools may nominate up to three students to receive one of these admirable awards. This year, 209 COBIS students from 83 COBIS Schools were given this accolade. These students have been presented with a COBIS Student Achievement Award for the following reasons: • Outstanding academic achievement • Sustained, high level contributions to the wider life of the school • Significant contributions to the school’s/community’s charity activities • An act of bravery in the school/community The list below shows all the students who won a COBIS Student Achievement Award 2019 with confirmed consent for publication. School Student Adorable British College Chizitelu Ujah Adorable British College Somtochukwu Onugu Adorable British College Chidera Anichukwu Al Khor International School Sharjeel Zaman Malik Al Khor International School Michelle Chiam Wan Zhen Al Khor International School Abdul Saboor Aloha College Marbella Khalil Fakhry Ortega Azerbaijan British College Nurgul Isazada Azerbaijan British College Nilgun Ozkundakchi Britannica International School, Shanghai Erik Cuc Britannica International School, Shanghai Wei Lin Paio Britannica International School, Shanghai Fletcher James British International School Al Khobar Shereen Fahmi British International School Al Khobar Noorhaan Noor British International School Al Khobar Kareem Hijazi British International School and Montessori Education Jacob Suffield British International School and Montessori Education Prisca Songo-Browne British International School and Montessori Education Oumu Balde British International School Bratislava Yoonjung Kim British International School Bratislava Isabella Holland British International School in Belgrade Maria Novakovic British International School in Belgrade Milica Djoric British International School of Stavanger Saskia Horne British International School of Stavanger S.A. -

Expats Express Kuwait!

expatsEEK! express kuwait! Kuwait’s first and only e-magazine for the Western minded expat NOVEMBER #3, 2011 Always wanted to write a book about your time in Kuwait? Someone just did! expats express kuwait! EEK! Free Subscription: [email protected] Kuwait’s first and only e-newsletter for the Western minded expat Issue #3 11/2011 “thousands of brands rushing online without thinking...” “No, no, no my dear, EEK! is NOT “ONLINE” anything, it is simply “e”. Yanni, you can say it is “PRINTED MEDIA DELIVERED IN A DIGITAL FORMAT”. And so it goes, in so many of our marketing pitches we, EEK!, have to explain that we are not an online entity, and that “e” does not mean “website”. I know this is preaching to the converted, but yikes folks, if you’re not subscribed you don’t get it! Get it?! LOL This whole issue of “e” has been a very interesting road to take. I recently met up with an old friend and we had a chat on where and what EEK! is and where it fits in in the local media landscape. “Dude, EEK! is like a printed blog” he said as his glasses fogged up from the coffee half an inch from his nose. This statement made me realize for the first time that “yes, EEK! isn’t just about news, its way too intimate for that!”. (And intimate it is let me tell you. We receive loads of mails from you, our subscribers, and we try to read each and every one - we’re doing our best to keep up...) But I digress.