741 7 U-007-307.90 Cowan, C. W., First Farmers of the Middle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEAC Bulletin 58.Pdf

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 72ND ANNUAL MEETING NOVEMBER 18-21, 2015 NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE BULLETIN 58 SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE BULLETIN 58 PROCEEDINGS OF THE 72ND ANNUAL MEETING NOVEMBER 18-21, 2015 DOUBLETREE BY HILTON DOWNTOWN NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE Organized by: Kevin E. Smith, Aaron Deter-Wolf, Phillip Hodge, Shannon Hodge, Sarah Levithol, Michael C. Moore, and Tanya M. Peres Hosted by: Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Middle Tennessee State University Division of Archaeology, Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation Office of Social and Cultural Resources, Tennessee Department of Transportation iii Cover: Sellars Mississippian Ancestral Pair. Left: McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture; Right: John C. Waggoner, Jr. Photographs by David H. Dye Printing of the Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 58 – 2015 Funded by Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, Authorization No. 327420, 750 copies. This public document was promulgated at a cost of $4.08 per copy. October 2015. Pursuant to the State of Tennessee’s Policy of non-discrimination, the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation does not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, religion, color, national or ethnic origin, age, disability, or military service in its policies, or in the admission or access to, or treatment or employment in its programs, services or activities. Equal Employment Opportunity/Affirmative Action inquiries or complaints should be directed to the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, EEO/AA Coordinator, Office of General Counsel, 312 Rosa L. Parks Avenue, 2nd floor, William R. Snodgrass Tennessee Tower, Nashville, TN 37243, 1-888-867-7455. ADA inquiries or complaints should be directed to the ADA Coordinator, Human Resources Division, 312 Rosa L. -

Ohio History Lesson 1

http://www.touring-ohio.com/ohio-history.html http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/category.php?c=PH http://www.oplin.org/famousohioans/indians/links.html Benchmark • Describe the cultural patterns that are visible in North America today as a result of exploration, colonization & conflict Grade Level Indicator • Describe, the earliest settlements in Ohio including those of prehistoric peoples The students will be able to recognize and describe characteristics of the earliest settlers Assessment Lesson 2 Choose 2 of the 6 prehistoric groups (Paleo-indians, Archaic, Adena, Hopewell, Fort Ancients, Whittlesey). Give two examples of how these groups were similar and two examples of how these groups were different. Provide evidence from the text to support your answer. Bering Strait Stone Age Shawnee Paleo-Indian People Catfish •Pre-Clovis Culture Cave Art •Clovis Culture •Plano Culture Paleo-Indian People • First to come to North America • “Paleo” means “Ancient” • Paleo-Indians • Hunted huge wild animals for food • Gathered seeds, nuts and roots. • Used bone needles to sew animal hides • Used flint to make tools and weapons • Left after the Ice Age-disappeared from Ohio Archaic People Archaic People • Early/Middle Archaic Period • Late Archaic Period • Glacial Kame/Red Ocher Cultures Archaic People • Archaic means very old (2nd Ohio group) • Stone tools to chop down trees • Canoes from dugout trees • Archaic Indians were hunters: deer, wild turkeys, bears, ducks and geese • Antlers to hunt • All parts of the animal were used • Nets to fish -

Shifting Deer Hunting Strategies As a Result of Environmental Changes Along the Little and Great Miami Rivers of Southwest Ohio and Southeast Indiana

Shifting Deer Hunting Strategies as a Result of Environmental Changes along the Little and Great Miami Rivers of Southwest Ohio and Southeast Indiana Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in Anthropological Sciences in the undergraduate colleges of the Ohio State University by Sydney Baker the Ohio State University April 2020 Committee: Robert A. Cook, Professor (Chair) Aaron R. Comstock, Lecturer (Committee Member) Department of Anthropology 2 Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to those who helped me with invaluable assistance during this study. First, I pay my deepest gratitude to my thesis supervisor, Professor Robert Cook, whose passion for Ohio archaeology is inspiring. With his persistent help and mastery of knowledge on Fort Ancient cultures, I was able to complete this project with pride. Next, I wish to thank my second thesis supervisor, Dr. Aaron Comstock, who is the hardest worker I know. Aaron is truly kind-hearted and his curiosity on the complexities of archaeology kept me fully engaged with this study, as he was the first to see its potential. The contribution of the Ohio State University is truly appreciated. Four years of outstanding education gave me the foundation needed for this research. The faculty members within the department of Anthropology ceaselessly work towards giving students every opportunity possible. I also express my gratefulness to Robert Genheimer and Tyler Swinney at the Cincinnati Museum Center, who allowed me access to their extensive artifact collection. Without this assistance, the project would not be nearly as encompassing. I also wish to acknowledge Dr. -

2004 Midwest Archaeological Conference Program

Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 47 2004 Program and Abstracts of the Fiftieth Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Sixty-First Southeastern Archaeological Conference October 20 – 23, 2004 St. Louis Marriott Pavilion Downtown St. Louis, Missouri Edited by Timothy E. Baumann, Lucretia S. Kelly, and John E. Kelly Hosted by Department of Anthropology, Washington University Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri-St. Louis Timothy E. Baumann, Program Chair John E. Kelly and Timothy E. Baumann, Co-Organizers ISSN-0584-410X Floor Plan of the Marriott Hotel First Floor Second Floor ii Preface WELCOME TO ST. LOUIS! This joint conference of the Midwest Archaeological Conference and the Southeastern Archaeological Conference marks the second time that these two prestigious organizations have joined together. The first was ten years ago in Lexington, Kentucky and from all accounts a tremendous success. Having the two groups meet in St. Louis is a first for both groups in the 50 years that the Midwest Conference has been in existence and the 61 years that the Southeastern Archaeological Conference has met since its inaugural meeting in 1938. St. Louis hosted the first Midwestern Conference on Archaeology sponsored by the National Research Council’s Committee on State Archaeological Survey 75 years ago. Parts of the conference were broadcast across the airwaves of KMOX radio, thus reaching a larger audience. Since then St. Louis has been host to two Society for American Archaeology conferences in 1976 and 1993 as well as the Society for Historical Archaeology’s conference in 2004. When we proposed this joint conference three years ago we felt it would serve to again bring people together throughout most of the mid-continent. -

1992 Program + Abstracts

The J'J'l!. Annual Midwest Archaeological Conference 1 1 ' ll\T ii~,, !,II !ffll}II II I ~\: ._~ •,.i.~.. \\\•~\,'V · ''f••r·.ot!J>,. 1'1.~•~'l'rl!nfil . ~rt~~ J1;1r:1ri WA i1. '1~;111.-U!!•ac~~ 1.!\ ill: 11111m I! nIn 11n11 !IIIIIIII Jill!! lTiili 11 HJIIJJll llIITl nmmmlllll Illlilll 1IT1Hllll .... --·---------- PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS October 16-18, 1992 Grand Rapids, Michigan F Con£eren ·, MAC 1992 Midwest Archaeological Conference 37!!! Annual Meeting October 16-18, 1992 Grand Rapids, Michigan Sponsored By: The Grand Valley State University Department of Anthropology and Sociology The Public Museum of Grand Rapids CONFERENCE ORGANIZING C0MMITIEE Janet BrashlerElizabeth ComellFred Vedders Mark TuckerPam BillerJaret Beane Brian KwapilJack Koopmans The Department of Anthropology and Sociology gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the following organizations for their assistance in planning the 1992 Midwest Archaeological Conference: The Grand Valley State University Conference Planning Office The Office of the President, Grand Valley State University The Anthropology Student Organization The Public Museum of Grand Rapids Cover Rlustration: Design from Norton Zoned Dentate Pot, Mound C, Norton Mounds 8f(!r/!lA_. ARCHIVES ;z.g-'F' Office of the State Archaeologist The Universi~i of Iowa ~ TlA<-, Geuetftf 1'l!M&rmation \"l,_ "2. Registration Registration is located on the second floor of the L.V. Eberhard Center at the Conference Services office. It will be staffed from 11:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. on Friday, Oct. 16; 7:30 a.m. to 3:00 p.m. on Saturday, Oct. 17; and from 7:30 a.m. -

Ohio Archaeologist Volume 41 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 41 NO. 1 * WINTER 1991 Published by SOCIETY OF OHIO MEMBERSHIP AND DUES Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are payable on the first of January as follows: Regular membership $15.00; husband and S A.S.O. OFFICERS wife (one copy of publication) $16.00; Life membership $300.00. Subscription to the Ohio Archaeologist, published quarterly, is included President James G. Hovan, 16979 South Meadow Circle, in the membership dues. The Archaeological Society of Ohio is an Strongsville, OH 44136, (216) 238-1799 incorporated non-profit organization. Vice President Larry L. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 Exec. Sect. Barbara Motts, 3435 Sciotangy Drive, Columbus, BACK ISSUES OH 43221, (614) 898-4116 (work) (614) 459-0808 (home) Publications and back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist: Recording Sect. Nancy E. Morris, 901 Evening Star Avenue Ohio Flint Types, by Robert N. Converse $ 6.00 SE, East Canton, OH 44730, (216) 488-1640 Ohio Stone Tools, by Robert N. Converse $ 5.00 Treasurer Don F. Potter, 1391 Hootman Drive, Reynoldsburg, Ohio Slate Types, by Robert N. Converse $10.00 OH 43068, (614)861-0673 The Glacial Kame Indians, by Robert N. Converse $15.00 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Dr., Plain City, OH 43064, (614)873-5471 Back issues—black and white—each $ 5.00 Back issues—four full color plates—each $ 5.00 immediate Past Pres. Donald A. Casto, 138 Ann Court, Lancaster, OH 43130, (614) 653-9477 Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are generally out of print but copies are available from time to time. -

2016 Athens, Georgia

SOUTHEASTERN ARCHAEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 ATHENS, GEORGIA BULLETIN 59 2016 BULLETIN 59 2016 PROCEEDINGS & ABSTRACTS OF THE 73RD ANNUAL MEETING OCTOBER 26-29, 2016 THE CLASSIC CENTER ATHENS, GEORGIA Meeting Organizer: Edited by: Hosted by: Cover: © Southeastern Archaeological Conference 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CLASSIC CENTER FLOOR PLAN……………………………………………………...……………………..…... PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS…………………………………………………………………….…..……. LIST OF DONORS……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..……. SPECIAL THANKS………………………………………………………………………………………….….....……….. SEAC AT A GLANCE……………………………………………………………………………………….……….....…. GENERAL INFORMATION & SPECIAL EVENTS SCHEDULE…………………….……………………..…………... PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 26…………………………………………………………………………..……. THURSDAY, OCTOBER 27……………………………………………………………………………...…...13 FRIDAY, OCTOBER 28TH……………………………………………………………….……………....…..21 SATURDAY, OCTOBER 29TH…………………………………………………………….…………....…...28 STUDENT PAPER COMPETITION ENTRIES…………………………………………………………………..………. ABSTRACTS OF SYMPOSIA AND PANELS……………………………………………………………..…………….. ABSTRACTS OF WORKSHOPS…………………………………………………………………………...…………….. ABSTRACTS OF SEAC STUDENT AFFAIRS LUNCHEON……………………………………………..…..……….. SEAC LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARDS FOR 2016…………………….……………….…….…………………. Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin 59, 2016 ConferenceRooms CLASSIC CENTERFLOOR PLAN 6 73rd Annual Meeting, Athens, Georgia EVENT LOCATIONS Baldwin Hall Baldwin Hall 7 Southeastern Archaeological Conference Bulletin -

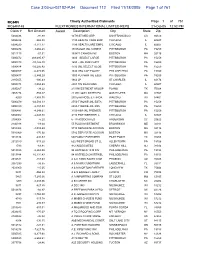

Case 3:03-Cv-02102-PJH Document 112 Filed 11/18/2005 Page 1 of 761

Case 3:03-cv-02102-PJH Document 112 Filed 11/18/2005 Page 1 of 761 MC64N Timely Authorized Claimants Page 1 of 761 MC64N148 FLEXTRONICS INTERNATIONAL LIMITED REPS 21-Oct-05 12:52 PM Claim #Net Amount Award Description City State Zip 5002436 -91.88 10TH ST MED GRP SAN FRANCISCO CA 94120 5004224 -965.80 1199 HEALTH CARE EMP CHICAGO IL 60607 5004220 -3,717.17 1199 HEALTHCARE EMPL CHICAGO IL 60607 5000476 -3,602.28 150 EAGLE JNL CORE E PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5011113 -57.51 159471 CANADA INC BOSTON MA 02116 5000472 -269,695.87 1600 - SELECT LARGE PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000473 -10,126.40 1650 - JNL FMR CAPIT PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000474 -93,205.42 1700 JNL SELECT GLOB PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5009707 -6,478.05 1838 LRG CAP EQUITY PHILADELPHIA PA 19109 5000477 -2,849.29 1900 PUTNAM JNL EQUI PITTSBURGH PA 15259 2185655 -100.43 1966 LP ST CHARLES IL 60174 5003474 -1,053.69 2001 TIN MAN FUND CHICAGO IL 60607 2095267 -38.22 210 INVESTMENT GROUP PLANO TX 75024 2057274 -755.37 22 WILLOW LIMITED PA OAK BLUFFS MA 02557 4259 -1,853.75 230 EAR NOSE & THROA WAUSAU WI 54401 5000479 -44,584.33 2750-T ROWE-JNL ESTA PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000480 -2,457.83 2850-T ROWE-JNL MID- PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5000481 -4,348.61 3150-AIM-JNL PREMIER PITTSBURGH PA 15259 5004002 -2,648.80 3180 PARTNERSHIP, L. CHICAGO IL 60607 2104008 -5.20 5 - W ASSOCIATES ANDERSON SC 29622 2146318 -83.04 55 PLUS INVESTMENT BRUNSWICK ME 04011 5010968 -4,083.69 5710 SEPARATE ACCOUN BOSTON MA 02116 5010969 -170.92 5782 SEPARATE ACCOUN BOSTON MA 02116 1013184 -230.59 5D FAMILY PARTNERS PILET POINT TX 76258 -

Indiana Archaeology

INDIANA ARCHAEOLOGY Volume 5 Number 2 2010/2011 Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Indiana Department of Natural Resources Robert E. Carter, Jr., Director and State Historic Preservation Officer Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) James A. Glass, Ph.D., Director and Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer DHPA Archaeology Staff James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson Cathy L. Draeger-Williams Cathy A. Carson Wade T. Tharp Editors James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson, Senior Archaeologist and Archaeology Outreach Coordinator Cathy A. Carson, Records Check Coordinator Publication Layout: Amy L. Johnson Additional acknowledgments: The editors wish to thank the authors of the submitted articles, as well as all of those who participated in, and contributed to, the archaeological projects which are highlighted. Cover design: The images which are featured on the cover are from several of the individual articles included in this journal. Mission Statement: The Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology promotes the conservation of Indiana’s cultural resources through public education efforts, financial incentives including several grant and tax credit programs, and the administration of state and federally mandated legislation. 2 For further information contact: Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology 402 W. Washington Street, Room W274 Indianapolis, Indiana 46204-2739 Phone: 317/232-1646 Email: [email protected] www.IN.gov/dnr/historic 2010/2011 3 Indiana Archaeology Volume 5 Number 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Authors of articles were responsible for ensuring that proper permission for the use of any images in their articles was obtained. -

A Comparison of Faunal Assemblages from Two Fort Ancient Villages

Exploring Environmental and Cultural Influences on Subsistence: A Comparison of Faunal Assemblages from Two Fort Ancient Villages Honors Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with honors research distinction in Anthropology in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Melissa French The Ohio State University December 2013 Project Advisor: Professor Robert Cook, Department of Anthropology 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Ohio State University and Cincinnati Museum Center for allowing me to use their comparative collections to identify the faunal remains used in this study. I would also like to thank the Social and Behavioral Sciences research grant program and the Sidney Pressey Honors & Scholars grant program for providing funds for me to take part in the excavation at Guard in 2012. Thanks to Jackie Lipphardt for teaching me about the joys of faunal analysis. Thank you to Dr. Jeffery Cohen and Dr. Greg Anderson for serving as my committee members for my oral examination. And finally, I would also like to thank my advisor Dr. Robert Cook for allowing me to use the faunal remains from Guard and Taylor in my study as well as for challenging, educating and guiding me during this process. 2 Table of Contents Page List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………………...4 List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………..............5 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………............6 Introduction…................................................................................................................................ -

Archaeologist Olume 25 Number 2 Spring 1975

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST OLUME 25 NUMBER 2 SPRING 1975 THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO The Archaeological Society of Ohio Officers Claude Britt, Jr., Many Farms, Arizona Ray Tanner, Behringer Crawford Museum, DeVou Park, President—Dana L. Baker, 1976 Covington, Kentucky West Taylor St., Mt. Victory Ohio William L. Jenkins, 3812 Laurel Lane, Anderson, Indiana Vice President—Jan Sorgenfrei, 1976 Mark W. Long, Box 467, Wellston, Ohio 7625 Maxtown Rd., Westerville, Ohio Steven Kelley, Seaman, Ohio Executive Secretary—Frank W. Otto, 1976 James Murphy, Dept. of Geology, Case Western Re 1503 Hempwood Dr., Cols., Ohio serve Univ. Cleveland, Ohio Treasurer—John J. Winsch, 1976 6614 Summerdale Dr., Dayton, Ohio Recording Secretary—Dave Mielke, 1976 Box 389, Botkins, Ohio Editorial Office and Business Office Editor—RobertN. Converse, 1978 199 Converse Drive, Plain City, Ohio 43064 199 Converse Drive, Plain City, Ohio Membership and Dues Trustees Annual dues to the Archaeological Society of Ohio are Ensil Chadwick, 119 Rose Avenue, payable on the first of January as follows: Regular mem Mt. Vernon, Ohio 43050 1978 bership $7.50; Husband and wife (one copy of publica Wayne A. Mortine, Scott Drive, Oxford Hgts., tion) $8.50; Contributing $25.00. Fundsare used for Newcomerstown, Ohio 1978 publishing the Ohio Archaeologist. The Archaeological Charles H. Stout, 91 Redbank Drive, Society of Ohio is an incorporated non-profit organiza Fairborn, Ohio 1978 tion and has no paid officers or employees. Alva McGraw, Route #11, Chillicothe, Ohio 1976 The Ohio Archaeologist is published quarterly and William C. Haney, 706 Buckhom St., subscription is included in the membership dues. Ironton, Ohio 1975 Ernest G. -

Violence and Environmental Stress During the Late Fort Ancient (AD 1425 - 1635) Occupations of Hardin Village

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2019 The Bioarchaeology of Instability: Violence and Environmental Stress During the Late Fort Ancient (AD 1425 - 1635) Occupations of Hardin Village Amber Elaine Osterholt Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons Repository Citation Osterholt, Amber Elaine, "The Bioarchaeology of Instability: Violence and Environmental Stress During the Late Fort Ancient (AD 1425 - 1635) Occupations of Hardin Village" (2019). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 3656. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/15778514 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BIOARCHAEOLOGY OF INSTABILITY: VIOLENCE AND ENVIRONMENTAL STRESS DURING THE LATE FORT ANCIENT (AD 1425 – 1635) OCCUPATIONS