In Search of Good Relationships to Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Search of 'The Good of Man': Georg Henrik Von Wright's Humanistic Ethics

In Search of ‘the Good of Man’: Georg Henrik von Wright’s Humanistic Ethics LASSI JAKOLA 1. In this paper I shall make an attempt at tracing one particu- lar path Georg Henrik von Wright travelled in the realm of values and moral philosophy.* More precisely, I shall have a look at some of von Wright’s discussions concerning the con- cept of ‘the good of man’ – a notion of which von Wright himself states at the beginning of the fifth chapter of his 1963 The Varieties of Goodness (henceforth also Varieties or VoG), that it “is the central notion of our whole inquiry”, and that “the problems connected with it are of the utmost difficulty” (VoG, 86). He continues: “Many of the things which I say about them may well be wrong. Perhaps the best I can hope for is that what I say will be interesting enough to be worth a refutation.” Von Wright’s discussion on the good of man in the Varie- ties has not escaped external criticism,1 but von Wright him- self also later grew dissatisfied with his earlier account and * I would like to thank Anita von Wright-Grönberg and Benedict von Wright for permission to quote from Georg Henrik von Wright’s un- published scientific correspondence and the two anonymous reviewers for their incisive comments on the content of this paper. I am also grateful to Erich Ammereller, Peter Hacker, Lars Hertzberg, Georg Meggle and Bernt Österman, who all read the penultimate draft of this paper and pro- vided me with comments and encouragement. -

Notat2001 1.Pdf (78.27Kb)

1 HiT notat nr 1/2001 Georg Henrik von Wright: Explanation of the human action An analysis of von Wright’s assumptions from the perspective of theory development in nursing history Sigrun Hvalvik Faculty of Health and Social Sciences Department of Health Studies Telemark College Porsgrunn 2001 HiT notat no. 1/2001 ISSN 1503-3759 (online) ISSN 1501-8520 (printed) Telemark College Post Box 203 N-3901 Porsgrunn Norway Telephone: +47 35 57 50 00 Fax: +47 35 57 50 01 Website: http://www.hit.no/ Printed by Reprographic Centre, Telemark College-Bø ã The author/Telemark College No part of this publication may be reproduced except in accordance with the Copyright Act, or the Act Relating to Rights in Photographic Pictures, or the agreements made with Kopinor, The Reproduction Rights Organisation of Norway 3 ABSTRACT The subject of this essay is chosen for the purpose of obtaining a deeper insight into various methodological aspects related to my forthcoming doctoral work; an historical biographical study of the Norwegian nursing pioneer, Bergljot Larsson (1883 – 1968). In the essay I claim that it is of great importance that the interpreter is explicit on the assumptions underlying his interpretations, and is aware of their influence on the theory developed. I further discuss how the Finnish philosopher, G.H. von Wright can affect the development of theory in nursing history by analyzing and evaluation his assumptions on human actions. The analyzes, evaluations and discussions take place within the theoretical framework of the American nurse scientist, Hesook Suzie Kim. Looking at von Wright from Kim’s perspective of the nursing knowledge system, makes it obvious that von Wright gives directions to aspects and phenomena of great significance to nursing. -

Healing the Rift: How G.H. Von Wright Made Philosophy Relevant to His Life

JOURNAL FOR THE HISTORY OF ANALYTICAL PHILOSOPHY HEALING THE RIFT: HOW G. H. VON WRIGHT MADE VOLUME 7, NUMBER 8 PHILOSOPHY RELEVANT TO HIS LIFE EDITOR IN CHIEF BERNT ÖSTERMAN MARCUS ROSSBERG, UnIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT EDITORIAL BOARD In the introductory “Intellectual Autobiography” of the Georg ANNALISA COLIVA, UC IRVINE Henrik von Wright volume of the Library of Living Philosophers HENRY JACKMAN, YORK UnIVERSITY series, von Wright mentions the discrepancy he always felt be- FREDERIQUE JANSSEN-LaURet, UnIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER tween his narrow logical-analytical professional work and a drive KEVIN C. KLEMENt, UnIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS to make philosophy relevant to his life, calling it a rift in his philo- CONSUELO PRETI, THE COLLEGE OF NEW JERSEY sophical personality. This article examines the nature of the rift ANTHONY SKELTON, WESTERN UnIVERSITY and the various stages the problem went through during von MARK TEXTOR, KING’S COLLEGE LonDON Wright’s career. It is argued that the initial impression that his AUDREY YAP, UnIVERSITY OF VICTORIA books The Varieties of Goodness and Explanation and Understanding RICHARD ZACH, UnIVERSITY OF CALGARY had contributed to healing the rift, was subdued by a gradual shift in existential focus from individualistic ethics towards a EDITOR FOR SPECIAL ISSUES critical concern for destructive ways of thinking inherent in the SANDRA LaPOINte, MCMASTER UnIVERSITY Western culture, connected with von Wright’s “political awak- ening” at the end of the 1960s. The most urgent questions of REVIEW EDITORS our times called for novel, non-analytical, ways of doing phi- SEAN MORRIS, METROPOLITAN STATE UnIVERSITY OF DenVER losophy, employed in von Wright’s later works on science and SANFORD SHIEH, WESLEYAN UnIVERSITY reason, and the myth of progress. -

Pessimism As Worldview

PESSIMISM AS WORLDVIEW Finnish philosopher Georg Henrik von Wright (1916-2003) is one of the foremost logicians of the 20th century, whose status was truly set in stone when he succeeded Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) at Cambridge. Outside the action typologies, von Wright’s logic is too technical and too deep into the realm of analytic philosophy for me to fully understand. But then it is not as an analytical philosopher that I have read and been moved by Georg Henrik von Wright since the age of seventeen. While still in high school, I read his Tanke och förkunnelse [Thought and prophecy] (1955), a book about Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) and Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821-81). This reading experience was for me a watershed. Von Wright appeared as a philosopher who understood that logic alone could not give meaning to life. I felt his gravity. Life became an important thing. But I believe von Wright’s methods also fascinated me from the start. He framed his thinking with the help of fiction writers, engaged in dialog with them even though they were dead; he knew that Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky had experienced fundamental things about humanity’s existential being and about history. A humanist philosophy unfurled; thought in which history played a starring role and had to do with worldviews. I began my post-graduate education in the late 1970s by reading von Wright’s Explanation and Understanding. It was not easy. But I still believe it was worth the effort: I have since been equipped to discuss similarities and differences between the sciences and the humanities. -

Pdf På Webben

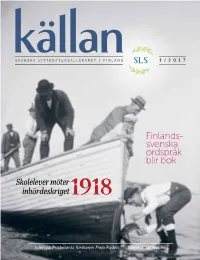

SVENSKA LITTERATURSÄLLSKAPET I FINLAND SLS 1/2017 Finlands svenska ordspråk blir bok Skolelever möter inbördes kriget1918 Intervju: Prisbelönta forskaren Freja Rudels Bildskatt på webben 6 INNEHÅLL 1 Ledare 4 Målmedveten satsning på digital utgivning 5 SLS firade #kvinnovecka 6 Vetenskap, moral och social aktivism 10 Skolelever lär känna människorna mitt i inbördeskriget 17 Imponerande paket i utmanande läge 18 Ordspråken som tog över 20 Anställning gav forskningsro 23 Kvällar med kunglig glans 24 Ordföranden som försökte gräva fram skelett ur sällskapsgarderoben Wrede och jag hade kommit för upp, ropande: ”Framåt poj- 26 Milispråket i Drakan långt utanför och framför vår högre kar – eteen päin!” Vi slä- 30 Från förälskelse till analys flygel, där kulorna veno mer än som pade honom ut ur kulregnet och 10 30 32 Mångskiftande material samsas var nyttigt. Vi tryckte i snön och förde honom till förbandsplatsen. på SLS arkivhyllor fyrade på med våra pistoler (mau- I rasande fart bar det därefter i väg 38 Pris, stipendier och understöd ser) i väntan på att vår skyttelinje mot huvudkvarteret och efter den skulle hinna utväcklas och öppna skakande släden travade Wredes 42 Hela livet bevarat i bilder eld. Vår kulspruta knattra på sitt livshäst med tom sadel. 43 Guldkorn ur arkivet hemtrevliga sätt, och Wrede reste ”Ge dem, ge dem, säg till pojkarna 44 Nya böcker från SLS sig upp. ”Framåt, framåt” ropade att de ge dem!” var hans sista ord, 46 Café Svenskfinland han och vi hoppade som harar över innan vanmakten kom och skänkte 47 SLS föredragsserie hösten 2017 drivorna mot fienden. Så vände han ro åt hans oroligt arbetande Rabbe hade en anteck sig om, likblek i ansiktet: ”Jag tror de bröst. -

The Von Wright and Wittgenstein Archives in Helsinki (WWA): a Unique Resource

The von Wright and Wittgenstein Archives in Helsinki (WWA): A Unique Resource Bernt Österman / Thomas Wallgren, Helsinki, Finland www.helsinki.fi/wwa Introduction von Wright are probably less well known. The autobiogra- phy Mitt liv som jag minns det (“My Life as I Remember It”) The von Wright and Wittgenstein Archives, WWA, is a has been translated only into the other language of his research resource at the Department of Philosophy, His- home country, Finnish. tory, Culture and Art Studies at the University of Helsinki, located at the philosophy unit. Although it roots goes back Georg Henrik von Wright was born in Helsinki 14th to the 1960s when the late professor Georg Henrik von of June 1916, and died on 16th of June 2003. Already at Wright started to form his Wittgenstein-archives, WWA is an early stage he seems to have known that he would currently re-establishing itself at the University of Helsinki become a philosopher (Vilkko 2005, 1). Under the influ- with a new location and administration. ence of his first teacher at the University of Helsinki, the Finnish philosopher Eino Kaila, von Wright became con- Activities of WWA may be divided into three groups. vinced that logical positivism finally had paved the way for WWA provides basic logistical and scientific support to philosophy as a proper science – in his autobiography he visiting scholars who benefit from the unique resources even speaks about logical positivism as the “Galilean turn kept at WWA. It seeks to ensure immediate, effective of philosophy” (von Wright 2001, 18). availability of its materials while also securing long-term preservation. -

Hela Numret Som PDF-Fil

2009 Hundraandra årgången Nr 1 ”BÖCKER från alla kunskapsområden”. Affisch för Leningrads statliga förlag LENGIZ. Aleksandr Rodtjenko, 1925. Kommentarer: Mellanösternmetaforer Charlotte Sundström & Tom Östling Romanen lyste med sin närvaro Marit Lindqvist Uttalsövningar i sömnens språklaboratorium Nalle Valtiala Agatha Christie i gyckelbyxor Timo Hämäläinen Finlandia i moll Susanna Fellman Finland, Sverige och den kinesiska ekonomins framtidsutsikter Tom Reuter Schildt och von Wright Lösnummer 5,00 €, i Sverige 50 kr. REDAKTION: Huvudredaktör Trygve Söderling Redaktionssekreterare Barbro Enckell-Grimm Niklas Bruun, Kristian Donner, Susanna Fellman, Nils Erik Forsgård, Barbro Holmberg, Martina Reuter, Tom Sandlund, Folke Stenman, Charlotte Sundström, Ingmar Svedberg, Tom Söderman, Clas Zilliacus, Tom Östling Manuskript till Trygve Söderling, Broholmsudden 3 C 21, 00530 Helsingfors, tfn 7592 592 Barbro Enckell-Grimm, Linnankoskigatan 24 A 1, 00250 Helsingfors, tfn 406 345 (fm, kväll) fax 406 934 Prenumerationer, honorar och arvoden: Barbro Enckell-Grimm, Linnankoskigatan 24 A1, 00250 Helsingfors E-post: [email protected] http:// www.kolumbus.fi/nya.argus PRENUMERATIONS- och ANNONSKONTOR: Postbox 52, 00251 Helsingfors. Prenumerationspris: 1/1 år 40 € 1/2 år 25 €, i Sverige 1/1 år 400,– Skr, 1/2 år 250,– Skr. Annonser: 1/1 sida 100 € 1/2 sida 70 € 1/4 sida 50 € Sampo 800014-102076; Sparbanken Aktia, checkräkning 405511-13963 BIC: PSPBFIHH SWIFT: FI10 8000 1400 1020 76. I detta nummer medverkar: Trygve Söderling huvudredaktör för Nya Argus, Helsingfors Susanna Fellman docent i ekonomisk och social historia, Helsingfors Timo Hämäläinen litteraturkritiker, ledamot för bedömningskommittén för Nordiska rådets litteraturpris, Helsingfors Marit Lindqvist radioredaktör, Ingå Tom Reuter professor em., Helsingfors Charlotte Sundström journalist, kritiker, Helsingfors Nalle Valtiala modersmålslärare, författare, Grankulla Tom Östling redaktör, Karis Modellen på det inklippta fotot är Lili Brik, känd bland annat som poeten Vladimir Maja- kovskijs musa. -

Walking and Talking with Georg Henrik Von Wright

Walking and Talking with Georg Henrik von Wright An early memory of Georg Henrik von Wright from my student days: he is walking back and forth in a hallway in the University of Helsinki, carrying on a lively discussion with some other philosopher, I forget who. His walk, with its short, efficient steps, body slightly bent forward, fast but not rushed, is perfectly matched by his way of talking, his voice distinct and energetic, uttering well-formed sentences with a beautiful cadence, fast but not rushed. Then as later, von Wright had a strong physical presence. His bushy eyebrows and blond hair (imperceptibly turning into grey over the years) as well as his ruddy complexion gave an impression of health, matched by his affable manner and cheerful spirits – though getting to know him meant getting to realize that his exterior hid a health that was not always so sturdy, just as his apparent cheerfulness camouflaged a strong tendency to worry: about his family’s safety, academic life in Finland, world peace, the state of the environment. Long before I got to know von Wright, he was a well-known figure for me. In high school, I had plans to study philosophy, and I read his well-known overview of contemporary philosophy Logik, filosofi och språk [Logic, philosophy and language]. Yet when time came to enroll at Helsinki, in 1961, my courage failed me and I decided it would be more opportune to take up modern languages. After two years of that, my then fiancée and present wife, Anki (not a philosopher herself), had had enough of it and got me to realize that, whatever the career prospects, I would be happier as a philosopher. -

På Besök Hos Ulla-Lena Lundberg I Diktarhemmet

SVENSKA LITTERATURSÄLLSKAPET I FINLAND SLS 1/2018 På besök hos Ulla-Lena Lundberg i Diktarhemmet De kodar Topelius Politisk poesi Georg Henrik von Wright 5 INNEHÅLL 1 Ledare 5 Guldkorn ur arkivet 6 Fruktbar spänning mellan dikt och ideologi 7 Politiken som marknadsplats 8 De kodar Topelius värld 16 Diktarhemmet ska vara ett litteraturens hus 20 En fristad för litteraturen 22 Digert detektivarbete ledde till Björlingbiografi 24 Rösterna bakom insamlingsmaterialen 25 Nytt ljus på Georg Henrik von Wright 29 Expert på integration i Svenskfinland 8 30 Från författararkiv till ungdomsdanser 36 Pris, stipendier och understöd 38 En bit estnisk historia på Finna 40 Nytt ur SLS utgivning 45 Föredragsserien hösten 2018 16 38 Källan. Svenska litteratursällskapet informerar 1/2018 (25:e årgången). Utgivare: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland, PB 158, 00171 Helsingfors. www.sls.fi, tfn 09 618 777, e-post: [email protected] Ansvarig utgivare: Marika Mäklin. Redaktörer: Malin Bredbacka-Grahn, Hedvig Rask, Frida Wickholm. Övriga redaktionsmedlemmar: Nina Edgren- Henrichson, Christer Kuvaja, Kristina Linnovaara, Jonas Lång, Jennica Thylin- Klaus. Layout: Antti Pokela. Fotograf (när inte annat anges): Janne Rentola. Arkiv bilder ur egna samlingar. Tryck: Trinket Ab, Helsingfors 2018. ISSN-L 1237-8356. ISSN (print) 1237-8356. ISSN (online) 2242-6787. Arkivbildernas signum: s. 11 SLSA 801, s. 21 SLSA 904 och SLS 1555, s. 22 SLSA 1063, s. 24 SLSA 996, s. 31 ÖTA 335, s. 32 SLSA 1375, s. 34 SLS 2318, s. 35 ÖTA 327 och ÖTA 324, s. 38–39 SLS 445 LEDARE PAULINE VON BONSDORFF Estetiska praktiker i förändring – och SLS? En bildad herre visade nyligen en viss – snabbt undanstuvad – förvåning över att skönlittera turen bara är en liten del av de angelägen heter Svenska litteratursällskapets verksam het handlar om. -

Progress by Enlightenment: Fact Or Fiction?1

Progress by Enlightenment: Fact or Fiction?1 ILKKA NIINILUOTO University of Helsinki The public use of one’s reason must always be free, and it alone can bring about enlightenment among mankind Immanuel Kant (1784) Enlightenment is a powerful intellectual and cultural movement which has vigorously promoted the idea of progress. However, the value-laden notion of progress is in many ways ambiguous even when it is restricted to some special area, such as science, art, technology, or politics. Some critics, who otherwise favor the Enlightenment commitment to education and research, have argued that progress is a myth. Some others regard Enlightenment as a transitory period of modernity, already surpassed by disillusioned postmodernism. Considering the philosophical aspects of these debates, my melioristic conclusion in this article is that progress is still a viable pos- sibility or prospect: even though there is no general historical law which would make progress of the humanity necessary, it is up to us to hold up the values of the Enlightenment in our striving for a better world. History of Progress In his classic study of the idea of progress, J. B. Bury (1955) argued that the conception of progress in human history was established only by the optimist thinkers of the Enlightenment. In the narrow sense, Enlighten- ment is defined as an intellectual trend from the mid-seventeenth century to the late eighteenth century (cf. Gay, 1973). Using light as a metaphor,2 its advocates argued that education can give freedom from superstition and religious dogmatism, if its content is provided by scientific inquiry. -

2017 Issn 0015-248X

Grundl aGd 1876 av C. G. Es tl andEr 2017 ISSN 0015-248X KULTUR EKONOMI POLITIK Redaktion Jutta Ahlbeck Ansvarig chefredaktör Freja Rudels Redaktionssekreterare Redaktionsråd Martina Björklund Mats Börjesson Pekka Kettunen Nina Kivinen Else-Britt Kjellqvist Bengt Kristensson Uggla Tage Kurtén Kristina Malmio Sverker Sörlin Ulrika Wolf-Knuts Utgivare Föreningen Granskaren r.f. Åbo Ordförande Pia Maria Ahlbäck Jutta Ahlbeck Margrét Halldórsdóttir Carina Gräsbeck Jonas Lagerström Hanna Lindberg Ann-Charlotte Palmgren Julia Tidigs Formgivning Oy Graaf Ab Tryckning Oy Nordprint Ab Kontakt Redaktionen: [email protected] Prenumerationer: [email protected] Mer om oss www.abo.fi/public/finsktidskrift Instruktioner för skribenter: www.abo.fi/public/finsktidskriftinstr Om prenumerationer: www.abo.fi/public/finsktidskriftpren Bidragsgivare Svenska Litteratursällskapet i Finland, Svenska Kulturfonden, Föreningen Konstsamfundet, Kulturfonden Island-Finland, Wil- liam Thurings Stiftelse, Kommerserådet Otto A. Malms Dona- tionsfond, Waldemar von Frenckells stiftelse Innehåll 7–8/2017 Chefredaktör Jutta Ahlbeck Att ställa frågor till det förflutna 5 Kollegialt granskade artiklar Britt-Marie Villstrand En minnesvärd man. Biskop Mikael Agricola i 1800-talets bildkonst och litteratur 7 Anna Hollsten ”Orfeus sjunger om sorg”. Familjeelegin i Gösta Ågrens författarskap 29 Essäer Bernt Österman ”Jag kan inte låta bli att oupphörligt jämföra honom med Cézanne”. Hur Göran Schildt hjälpte Georg Henrik von Wright att lösa problemet Ludwig Wittgenstein 51 Anders Björnsson En rättvis eller orättvis betraktelse. Reformatorn Stellan Arvidson, hans öde och eftermäle 67 Jonas Ahlskog Vårt praktiska och historiska förflutna 77 Granskaren Harriet Silius Står kvinnorna för samhällsutvecklingen? Varför klarar sig flickor bättre i skolan? 84 Pia Mikander Vem är utvecklingens subjekt? 87 Mio Lindman Den upphöjde filosofen och den provokativa pessimisten 90 Christian Braw Finlands Mannerheim 96 FINSK TIDSKRIFT 7/2017 Att ställa frågor till det förflutna Det är dags för årets sista nummer. -

Kirjaston Paluu

KANSALLISKIRJASTO 1/2016 KIRJASTON PALUU s. 14 Rouva Jenni Haukion avajaispuhe / s. 5 Kirjaston palvelut uudistuivat / s. 36 Georg Henrik von Wrightin satavuotisnäyttely SISÄLLYS 1/2016 1 19 Pääkirjoitus: Kaupungin kaunein konservointi Kansalliskirjaston avajaiset yleisölle 1. maaliskuuta 2016 2 Den vackraste restaureringen i staden 24 Kai Ekholm Peruskorjaus kuvina Kati Winterhalter 3 Ajankohtaista 32 4 Kirjaseikkailuja – Kansalliskirjaston Minun Kansalliskirjastoni: Jukka Viikilä 375-vuotisjuhlanäyttely Galleriassa Kirsi Aho Inkeri Pitkäranta 5 36 Kansalliskirjaston uusi palvelukonsepti Sata vuotta Georg Henrik von Wrightin ennakoi asiakkaiden toiveita syntymästä – näyttely Ajatus ja julistus Jussi Omaheimo Rotundassa 8 Risto Vilkko Vuosisatamme verkkoon! -kampanja tukee 40 kulttuuriperinnön säilyttämistä Mikä oli hakkapeliittojen rooli Strahovin Kristiina Hildén luostarin kirjaston ryöstössä Prahassa 10 vuonna 1648? Mika Hakkarainen Martat edelläkävijöinä talouden kiertoajattelussa Sinikka Salo 44 12 Kirjastossa tapahtuu TEEMA 48 Kirjaston paluu Näyttelyt ja tapahtumat 14 Tasavallan presidentin puolison puhe Kansalliskirjaston avajaisissa Jenni Haukio KANNEN KUVA: KATI WINTERHALTER, KUVANKÄSITTELY JARKKO HYPPÖNEN kai ekholm Ylikirjastonhoitaja, professori VEIKKO SOMERPURO VEIKKO PÄÄKIRJOITUS Kaupungin kaunein konservointi Missä onkaan kaupungin keskusta, mediassa kysytään joskus. Meille yli- opistolaisille se on itsestäänselvyys. Senaatin, Tuomiokirkon ja yliopiston muodostama kolmiyhteys on kansakunnan henkinen ydin. Matti Klinge kuvaa,