Wittgenstein and GH Von Wright's Path To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Search of 'The Good of Man': Georg Henrik Von Wright's Humanistic Ethics

In Search of ‘the Good of Man’: Georg Henrik von Wright’s Humanistic Ethics LASSI JAKOLA 1. In this paper I shall make an attempt at tracing one particu- lar path Georg Henrik von Wright travelled in the realm of values and moral philosophy.* More precisely, I shall have a look at some of von Wright’s discussions concerning the con- cept of ‘the good of man’ – a notion of which von Wright himself states at the beginning of the fifth chapter of his 1963 The Varieties of Goodness (henceforth also Varieties or VoG), that it “is the central notion of our whole inquiry”, and that “the problems connected with it are of the utmost difficulty” (VoG, 86). He continues: “Many of the things which I say about them may well be wrong. Perhaps the best I can hope for is that what I say will be interesting enough to be worth a refutation.” Von Wright’s discussion on the good of man in the Varie- ties has not escaped external criticism,1 but von Wright him- self also later grew dissatisfied with his earlier account and * I would like to thank Anita von Wright-Grönberg and Benedict von Wright for permission to quote from Georg Henrik von Wright’s un- published scientific correspondence and the two anonymous reviewers for their incisive comments on the content of this paper. I am also grateful to Erich Ammereller, Peter Hacker, Lars Hertzberg, Georg Meggle and Bernt Österman, who all read the penultimate draft of this paper and pro- vided me with comments and encouragement. -

Notat2001 1.Pdf (78.27Kb)

1 HiT notat nr 1/2001 Georg Henrik von Wright: Explanation of the human action An analysis of von Wright’s assumptions from the perspective of theory development in nursing history Sigrun Hvalvik Faculty of Health and Social Sciences Department of Health Studies Telemark College Porsgrunn 2001 HiT notat no. 1/2001 ISSN 1503-3759 (online) ISSN 1501-8520 (printed) Telemark College Post Box 203 N-3901 Porsgrunn Norway Telephone: +47 35 57 50 00 Fax: +47 35 57 50 01 Website: http://www.hit.no/ Printed by Reprographic Centre, Telemark College-Bø ã The author/Telemark College No part of this publication may be reproduced except in accordance with the Copyright Act, or the Act Relating to Rights in Photographic Pictures, or the agreements made with Kopinor, The Reproduction Rights Organisation of Norway 3 ABSTRACT The subject of this essay is chosen for the purpose of obtaining a deeper insight into various methodological aspects related to my forthcoming doctoral work; an historical biographical study of the Norwegian nursing pioneer, Bergljot Larsson (1883 – 1968). In the essay I claim that it is of great importance that the interpreter is explicit on the assumptions underlying his interpretations, and is aware of their influence on the theory developed. I further discuss how the Finnish philosopher, G.H. von Wright can affect the development of theory in nursing history by analyzing and evaluation his assumptions on human actions. The analyzes, evaluations and discussions take place within the theoretical framework of the American nurse scientist, Hesook Suzie Kim. Looking at von Wright from Kim’s perspective of the nursing knowledge system, makes it obvious that von Wright gives directions to aspects and phenomena of great significance to nursing. -

Diss2008kaipainen.Pdf (1.200Mb)

Suurten ajattelijoiden elämäkerrat ja elämänpolut Suurten ajattelijoiden elämäkerrat ja elämänpolut Bertrand Russellin, Ludwig Wittgensteinin ja Georg Henrik von Wrightin elämäkerrat bourdieulais-pragmatististen ja latourilaisten näkökulmien vertailussa Päivi Kaipainen KOULUTUSSOSIOLOGIAN TUTKIMUSKESKUS, RUSE RESEARCH UNIT FOR THE SOCIOLOGY OF EDUCATION, RUSE Koulutussosiologian tutkimuskeskuksen raportti 74 Kansi: Minna Rauhala ISSN 1235-9114 ISBN 951-29-3729-5 UNIPRINT, Turku 2008 Kiitokset Haluan aivan ensiksi kiittää esimiestäni ja ohjaajaani professori Osmo Kivistä mahdollisuudesta tehdä väitöskirjatyötä varsinaisen työni ohella Koulutussosiologian tutkimuskeskuksen koordinaattorina. Haluan myös kiittää häntä sekä kannustuksesta että rakentavasta kritiikistä, molemmat ovat olleet yhtä tarpeellisia. Työni esitarkastajina toimivat professori Risto Heiskala Tampereen yliopistosta ja dosentti Keijo Rahkonen Helsingin yliopistosta. Kiitän heitä käsikirjoitukseni läpikäymiseen uhraamastaan ajasta ja monista hyvistä korjausehdotuksista. Heidän kommenttinsa herättivät uusia ajatuksia ja auttoivat toivon mukaan parantamaan työni lopullista versiota. Kiitokset kuuluvat myös työtovereille, ystäville ja sukulaisille, jotka vahvistivat uskoani siihen, että työ vielä jonakin päivänä valmistuu ja on uurastuksen arvoinen. Turussa, 23. lokakuuta 2008 Päivi Kaipainen SISÄLLYSLUETTELO 1. JOHDANTO…………………………………………………….. 9 Tutkimuksen viitekehys………………………………………………….. 11 Elämäkertatutkimuksesta……………………………………............. 19 Bourdieulais–pragmatistinen lähestymistapa -

Healing the Rift: How G.H. Von Wright Made Philosophy Relevant to His Life

JOURNAL FOR THE HISTORY OF ANALYTICAL PHILOSOPHY HEALING THE RIFT: HOW G. H. VON WRIGHT MADE VOLUME 7, NUMBER 8 PHILOSOPHY RELEVANT TO HIS LIFE EDITOR IN CHIEF BERNT ÖSTERMAN MARCUS ROSSBERG, UnIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT EDITORIAL BOARD In the introductory “Intellectual Autobiography” of the Georg ANNALISA COLIVA, UC IRVINE Henrik von Wright volume of the Library of Living Philosophers HENRY JACKMAN, YORK UnIVERSITY series, von Wright mentions the discrepancy he always felt be- FREDERIQUE JANSSEN-LaURet, UnIVERSITY OF MANCHESTER tween his narrow logical-analytical professional work and a drive KEVIN C. KLEMENt, UnIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS to make philosophy relevant to his life, calling it a rift in his philo- CONSUELO PRETI, THE COLLEGE OF NEW JERSEY sophical personality. This article examines the nature of the rift ANTHONY SKELTON, WESTERN UnIVERSITY and the various stages the problem went through during von MARK TEXTOR, KING’S COLLEGE LonDON Wright’s career. It is argued that the initial impression that his AUDREY YAP, UnIVERSITY OF VICTORIA books The Varieties of Goodness and Explanation and Understanding RICHARD ZACH, UnIVERSITY OF CALGARY had contributed to healing the rift, was subdued by a gradual shift in existential focus from individualistic ethics towards a EDITOR FOR SPECIAL ISSUES critical concern for destructive ways of thinking inherent in the SANDRA LaPOINte, MCMASTER UnIVERSITY Western culture, connected with von Wright’s “political awak- ening” at the end of the 1960s. The most urgent questions of REVIEW EDITORS our times called for novel, non-analytical, ways of doing phi- SEAN MORRIS, METROPOLITAN STATE UnIVERSITY OF DenVER losophy, employed in von Wright’s later works on science and SANFORD SHIEH, WESLEYAN UnIVERSITY reason, and the myth of progress. -

Ilkka Niiniluoto PHILOSOPHY in FINLAND

Ilkka Niiniluoto PHILOSOPHY IN FINLAND: INTERNATIONAL CURRENTS AND NATIONAL CULTURAL DEBATES Philosophy is originally a product of Greek higher culture, which has been practised in Finland primarily as an academic discipline. According to a tradition starting from J. V. Snellman, Finnish philosophers have, besides their own research work, participated in public cultural debates and political life. In a small nation many leading thinkers have become generally well-known public figures. From 1313 onwards Finnish students attended the medieval University of Paris, where they had a chance to learn the scholastic way of integrating Christian theology and Aristotelian philosophy. In the sixteenth century the Finns studied the humanism of German reformation and the Renaissance philosophy of nature. In the Academy of Turku, founded in 1640, philosophy had a significant position in the basic studies, which included conceptual distinctions and the art of thinking (theoretical philosophy) as well as moral virtues and political principles (practical philosophy). During the Turku period, which ended when the university moved to Helsinki in 1828, Finnish philosophers did not gain notable original achievements, but their role was primarily to support learning and transmit new academic currents to the academic community. Among them one can mention Cartesianism based on the ideas René Descartes and Francis Bacon´s experimental research method at the end of the seventeenth century, and along the eighteenth century Christian Wolff’s rationalism, John Locke’s empiricism, Samuel Pufendorf’s doctrine of natural rights, and Immanuel Kant’s transcendental idealism. Snellman: from Hegel to national awakening It was eventually the breakthrough of G. W. F. -

Pessimism As Worldview

PESSIMISM AS WORLDVIEW Finnish philosopher Georg Henrik von Wright (1916-2003) is one of the foremost logicians of the 20th century, whose status was truly set in stone when he succeeded Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) at Cambridge. Outside the action typologies, von Wright’s logic is too technical and too deep into the realm of analytic philosophy for me to fully understand. But then it is not as an analytical philosopher that I have read and been moved by Georg Henrik von Wright since the age of seventeen. While still in high school, I read his Tanke och förkunnelse [Thought and prophecy] (1955), a book about Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) and Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821-81). This reading experience was for me a watershed. Von Wright appeared as a philosopher who understood that logic alone could not give meaning to life. I felt his gravity. Life became an important thing. But I believe von Wright’s methods also fascinated me from the start. He framed his thinking with the help of fiction writers, engaged in dialog with them even though they were dead; he knew that Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky had experienced fundamental things about humanity’s existential being and about history. A humanist philosophy unfurled; thought in which history played a starring role and had to do with worldviews. I began my post-graduate education in the late 1970s by reading von Wright’s Explanation and Understanding. It was not easy. But I still believe it was worth the effort: I have since been equipped to discuss similarities and differences between the sciences and the humanities. -

EPSA Newsletter 2013

EPSA Newsletter Vol. II, Issue 1 August 2013 Editor: Friedrich Stadler | Assistant Editor: Daniel Kuby SPECIAL EPSA13 HELSINKI EDITION Editorial TABLE OF CONTENTS Friedrich Stadler Editorial Friedrich Stadler 1 Dear members and colleagues, The Finnish Tradition of Philosophy of Science Ilkka Niiniluoto 3 On the occasion of the 4th Conference of the European Philosophy of Science Association in Helsinki, August 28-31, 2013, we are pleased to publicize the Welcome Address already third issue of our electronic EPSA Newsletter. Given the venue of the Uskali Mäki 8 conference it is mainly dealing with philosophy of science in Finland, which is a remarkable success story since the pioneering Eino Kaila for a smaller coun- EPSA Women’s Caucus: A Report try at the margins of Europe. In this regard we are pleased that Jaakko Hin- Kristina Rolin 10 tikka will also take part as a speaker in this event. Report on One of the contemporary prominent proponents of philosophy of science, GWP.2013 Ilkka Niiniluoto, the former Rector and Chancellor of the University of Hel- Holger Lyre 11 sinki in the last decade, provided a report on the origins and development of Report on Activities philosophy of science in Finland, where in 2015 also the 15th Congress of the of the Dutch Society International Union in History and Philosophy of Science/Division of Logic, for the Philosophy of Methodology and Philosophy of Science (IUHPS/DLMPS) will be organised. A Science report by Uskali Mäki, the chair of the Local Organising Committee on behalf F. A . M u l l e r 13 of the University of Helsinki and the Centre of Excellence in the Philosophy of the Social Sciences (TINT) complements this focus appropriately. -

Passmore, J. (1967). Logical Positivism. in P. Edwards (Ed.). the Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Vol. 5, 52- 57). New York: Macmillan

Passmore, J. (1967). Logical Positivism. In P. Edwards (Ed.). The Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Vol. 5, 52- 57). New York: Macmillan. LOGICAL POSITIVISM is the name given in 1931 by A. E. Blumberg and Herbert Feigl to a set of philosophical ideas put forward by the Vienna circle. Synonymous expressions include "consistent empiricism," "logical empiricism," "scientific empiricism," and "logical neo-positivism." The name logical positivism is often, but misleadingly, used more broadly to include the "analytical" or "ordinary language philosophies developed at Cambridge and Oxford. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND The logical positivists thought of themselves as continuing a nineteenth-century Viennese empirical tradition, closely linked with British empiricism and culminating in the antimetaphysical, scientifically oriented teaching of Ernst Mach. In 1907 the mathematician Hans Hahn, the economist Otto Neurath, and the physicist Philipp Frank, all of whom were later to be prominent members of the Vienna circle, came together as an informal group to discuss the philosophy of science. They hoped to give an account of science which would do justice -as, they thought, Mach did not- to the central importance of mathematics, logic, and theoretical physics, without abandoning Mach's general doctrine that science is, fundamentally, the description of experience. As a solution to their problems, they looked to the "new positivism" of Poincare; in attempting to reconcile Mach and Poincare; they anticipated the main themes of logical positivism. In 1922, at the instigation of members of the "Vienna group," Moritz Schlick was invited to Vienna as professor, like Mach before him (1895-1901), in the philosophy of the inductive sciences. Schlick had been trained as a scientist under Max Planck and had won a name for himself as an interpreter of Einstein's theory of relativity. -

This Volume on the Vienna Circle's Influence in the Nordic Countries

Vol. 8, no. 1 (2013) Category: Review essay Written by Carlo Penco This volume on the Vienna Circle’s influence in the Nordic countries gives a very interesting presentation of an almost forgotten landmark. In the years preceding the Second World War, European philosophy was at the high point of its intellectual vitality. Everywhere philosophical societies promoted a dense network of connections among scholars, with international meetings and strong links among individuals and associations. In this context, the Vienna Circle emerges as one of the many, also if probably the most well-known, centres of diffusion of a new style of philosophy, closely linked to the new logic and with a strongly empiricist attitude. At the same time, empiricism, formal logic and psychology constituted (and still constitute) the common background of most of the Nordic philosophers, a background which permitted them to develop connections with Vienna’s cultural environment (well known also for the work of psychologists such as Sigmund Freud, but also Charlotte and Karl Bühler). This piece of history, although limited to the connection between Nordic philosophy and Vienna Circle, helps to clarify the history of European philosophy, and the sharp difference of Nordic philosophy in respect of the development of philosophy in Southern and Central Europe in the half a century following the Second World War. The editors say in the introduction: . one of the least known networks of the Vienna Circle is the “Nordic connection”. This connection had a continuing influence for many of the coming decades, beginning with the earliest phase of the Vienna Circle and continuing with a number of adaptations and innovations well into contemporary times. -

Kaila for Yearbook

Ilkka Niiniluoto, Sami Pihlström (eds.), Reappraisals of Eino Kaila’s Philosophy. Acta Philosophica Fennica vol. 89, Societas Philosophica Fennica, Helsinki, 232pp., 30 €, ISBN 978–951–9264–75–2, ISSN 0355–1792. Eino Kaila (1890 – 1958) was the leading Finnish philosopher in the decades between 1930 and 1960. Nevertheless, for several decades he was internationally not very well-known since he published only in Finnish and German. This situation is changing. Meanwhile a considerable part of his work has been translated into English. Moreover, in the last twenty years or so, a considerable amount of secondary literature on Kaila (often in English) has been produced. I’d just like to mention the following sources: 1. Eino Kaila and Logical Empiricism (1992);1 2. Analytic Philosophy in Finland (2003);2 3. The Vienna Circle in the Nordic Countries (2010).3 For every reader who is seriously interested in 20th century Finnish philosophy these books are obligatory reading. Most of the publications collected in these volumes conceive of Kaila as an analytical philosopher - although already in 1992 Hintikka pointed out that this holds only with some important qualifications. In contrast, many papers in Reappraisals of Eino Kaila’s Philosophy (henceforth Reappraisals) take also into account aspects of Kaila’s thought that are related to other philosophical traditions, in particular to German Neo- kantianism and American pragmatism. From Reappraisals a richer picture of Kaila’s philosophy emerges from which it transpires that he certainly cannot be considered as an 1 Ilkka Niiniluoto, Matti Sintonen, Georg H. von Wright (eds.), Eino Kaila and Logical Empiricism, Acta Philosophica Fennica 52, Helsinki, Hakapaino Oy, 1992. -

Pdf På Webben

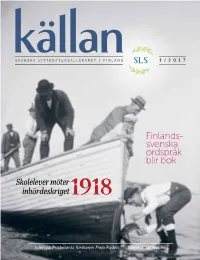

SVENSKA LITTERATURSÄLLSKAPET I FINLAND SLS 1/2017 Finlands svenska ordspråk blir bok Skolelever möter inbördes kriget1918 Intervju: Prisbelönta forskaren Freja Rudels Bildskatt på webben 6 INNEHÅLL 1 Ledare 4 Målmedveten satsning på digital utgivning 5 SLS firade #kvinnovecka 6 Vetenskap, moral och social aktivism 10 Skolelever lär känna människorna mitt i inbördeskriget 17 Imponerande paket i utmanande läge 18 Ordspråken som tog över 20 Anställning gav forskningsro 23 Kvällar med kunglig glans 24 Ordföranden som försökte gräva fram skelett ur sällskapsgarderoben Wrede och jag hade kommit för upp, ropande: ”Framåt poj- 26 Milispråket i Drakan långt utanför och framför vår högre kar – eteen päin!” Vi slä- 30 Från förälskelse till analys flygel, där kulorna veno mer än som pade honom ut ur kulregnet och 10 30 32 Mångskiftande material samsas var nyttigt. Vi tryckte i snön och förde honom till förbandsplatsen. på SLS arkivhyllor fyrade på med våra pistoler (mau- I rasande fart bar det därefter i väg 38 Pris, stipendier och understöd ser) i väntan på att vår skyttelinje mot huvudkvarteret och efter den skulle hinna utväcklas och öppna skakande släden travade Wredes 42 Hela livet bevarat i bilder eld. Vår kulspruta knattra på sitt livshäst med tom sadel. 43 Guldkorn ur arkivet hemtrevliga sätt, och Wrede reste ”Ge dem, ge dem, säg till pojkarna 44 Nya böcker från SLS sig upp. ”Framåt, framåt” ropade att de ge dem!” var hans sista ord, 46 Café Svenskfinland han och vi hoppade som harar över innan vanmakten kom och skänkte 47 SLS föredragsserie hösten 2017 drivorna mot fienden. Så vände han ro åt hans oroligt arbetande Rabbe hade en anteck sig om, likblek i ansiktet: ”Jag tror de bröst. -

The Von Wright and Wittgenstein Archives in Helsinki (WWA): a Unique Resource

The von Wright and Wittgenstein Archives in Helsinki (WWA): A Unique Resource Bernt Österman / Thomas Wallgren, Helsinki, Finland www.helsinki.fi/wwa Introduction von Wright are probably less well known. The autobiogra- phy Mitt liv som jag minns det (“My Life as I Remember It”) The von Wright and Wittgenstein Archives, WWA, is a has been translated only into the other language of his research resource at the Department of Philosophy, His- home country, Finnish. tory, Culture and Art Studies at the University of Helsinki, located at the philosophy unit. Although it roots goes back Georg Henrik von Wright was born in Helsinki 14th to the 1960s when the late professor Georg Henrik von of June 1916, and died on 16th of June 2003. Already at Wright started to form his Wittgenstein-archives, WWA is an early stage he seems to have known that he would currently re-establishing itself at the University of Helsinki become a philosopher (Vilkko 2005, 1). Under the influ- with a new location and administration. ence of his first teacher at the University of Helsinki, the Finnish philosopher Eino Kaila, von Wright became con- Activities of WWA may be divided into three groups. vinced that logical positivism finally had paved the way for WWA provides basic logistical and scientific support to philosophy as a proper science – in his autobiography he visiting scholars who benefit from the unique resources even speaks about logical positivism as the “Galilean turn kept at WWA. It seeks to ensure immediate, effective of philosophy” (von Wright 2001, 18). availability of its materials while also securing long-term preservation.