Joint Education Needs Assessment Northeast Nigeria November 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

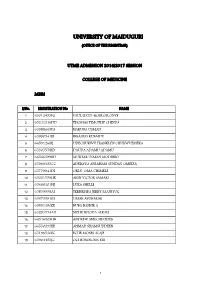

University of Maiduguri Utme Admission

UNIVERSITY OF MAIDUGURI (OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR) UTME ADMISSION FOR 2017/2018 ACADEMIC SESSION COLLEGE OF MEDICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF MEDICINE AND SURGERY S/No. Reg. No Name of Candidate 1 76186593GA MUHAMMED MUSABIRA MBBS 2 75616150BI ALI JUMMA'A SA'ADATU MUHAMMAD MBBS 3 75225603JD BELLO MAHASIN MBBS 4 75228686FJ TOGBORESO LOKPANE JAVAV MBBS 5 75234576ED BRUNO O CLEMS MBBS 6 75853832BJ ADEKOYA SEUN MBBS 7 76074976GH HASANA J DANIEL MBBS 8 75072297DH PIUS PAULINUS WARIGASU MBBS 9 75922039GI ABU OLUWAFEMI SUCCESS MBBS 10 75226335DB OLADOSU ABDULRASAQ OLALEKAN MBBS 11 76772693HJ CHARLES ANIYIN MBBS 12 75071512GE NEHEMIAH NGATI ULEA MBBS 13 75596581EA YUNUSA UMAR MBBS 14 77174029DF YUNUSA SHAMSI MBBS 15 75232914IC SHALTUT AHMAD MUHAMMAD MBBS 16 75962393GC GBOGBO JOSEPH OGHENEOCHUKO MBBS 17 76169985CG AMBI YAHAYA SALEH MBBS 18 75343406FF TOBALU FELIX AIGBOKHAI MBBS 19 75230208FC TUMBA CHRISTOPHER SUNDAY MBBS 20 75231817HF PHILIP PRISCILLIA DIBAL MBBS 21 75223796IC OLUKUNLE BOLANLE IRETUNDE MBBS 22 75966302HC UMEH FORTUNE CHIMA MBBS 23 76055844DJ ABASS ABDULLATEEF RAJI MBBS 24 76770023DI UDECHUKWU PROMISE CHIDI MBBS Page 1 of 144 25 75069790IJ JESSE TAIMAKO MBBS 26 75356959DJ ONOJA ANTHONY MATHEW MBBS 27 75475076CJ MUHAMMAD ABBAS BELLO MBBS 28 75225451GE NGGADA SAMUEL DAVID MBBS 29 76770533GA HARUNA ABUBAKAR YIRASO MBBS 30 75229251BD ABDU YUSUF LAWAN MBBS 31 76187405EJ YUSUF FATIMAZARA WASILI MBBS 32 77084690EB OZIGI PIUS JOHN ASUKU MBBS 33 75482315EA MUSA ILIYA MBBS 34 75550189CB TITUS FRIDAY MBBS 35 75174715HJ UMORU HARUNA MAINA MBBS -

Climate-Smart Agriculture in Yobe State of Nigeria

Climate-Smart Agriculture in Yobe state of Nigeria Climate-smart agriculture (CSA) considerations A• Agriculture is the mainstay for Yobe state economy P adaptation. There is the need to also integrate mitigation employing over 80 percent of the population. P M into the state’s climate-smart agriculture development Agricultural practices in the state are mainly rain-fed efforts. In addition, off-farm services related to CSA need with majority of the farmers engaged in small scale to be enhanced, including weather-smart and market- subsistence farming with millet, sorghum, cowpea and smart services. maize as major food crops and gum arabic, groundnut, sesame seed and cotton as cash crops. I• The Yobe state government places high priority on A significant proportion of the population are the development of the agricultural sector in the state. pastoralists rearing livestock such as cattle, sheep, The state ministry of agriculture is saddled with the goats, donkeys and horses at commercial level. responsibility of implementing agricultural policies that enables CSA. The broad strategic goals include A• The agricultural sector in the state is struggling to meet creating an operating environment that supports rapid the increasing food demand for its growing population modernization of agricultural production, processing, P as it battles with low productivity arising limited storage and distribution through supportive government investments, low farm input use, land tenure and climate policies. variability. In addition, the problem of flash floods, high temperature and incidences of pests and diseases have $• Funding for CSA is limited in the state and Nigeria in also aggravated the irrigation and upland farmers’ losses general, however there are opportunities to access and which consequently increase the incidence of poverty and utilize international climate finance from sources such as malnutrition in the state. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

Borno State, Nearly Tarmuwa Magumeri Kala/ Fune Jere Mafa 60 000 People Face the Threat of Famine Balge Nangere Dikwa (Phase 5)

N°32 SAHEL AND MAPSMARCH & FACTS 2016 WEST AFRICA Club No 44, November 2016 ONE OUT OF THREE PEOPLE IN NORTHEASTERN NIGERIA FACED WITH ACUTE FOOD INSECURITY August-September 2016 ccording to the fi ndings of the 1 Lake A Cadre harmonisé analysis of Abadam Yusufari Chad August 2016, some 4.4 million people in Yunusari Machina Mobbar Kukawa northeastern Nigeria were facing acute Nguru Karasuwa Guzamala food insecurity (phases 3-5) requiring Bade Borsari Mobbar urgent humanitarian assistance. In Bade Geidam Nganzai Monguro the worst affected and less acces- Jakusko Marte Yobe Ngala sible pockets of Borno state, nearly Tarmuwa Magumeri Kala/ Fune Jere Mafa 60 000 people face the threat of famine Balge Nangere Dikwa (phase 5). Boko Haram attacks and Damaturu Kaga Maiduguru Potiskum Konduga Bama suicide bombings continue to cause Fika Gujba fatalities and large-scale population Borno Gwoza displacement. This has had a negative Damboa Gulani impact on food consumption and Biu Chibok Madagali livelihood activities within both Askira/Uba Kwaya Michika displaced and host community house- Kusar Hawul Hong Bayo Mubi North holds. The situation continues to Shani Girie be particularly alarming in Borno, Mubi South Shelleng Maina Adamawa and Yobe which host large Song Adamawa numbers of internally displaced Lamurde people (IDPs). According to the Inter- Numan Gombi Demsa Yola North national Organization for Migration’s Yola South (IOM) June 2016 report, there are over Fufore Mayo- 1.4 million IDPs in Borno, 159 445 in Lake Abadam Bel Yusufari Chad Jada Yunusari Machina Mobbar Kukawa Adamawa and 111 671 in Yobe. New Phases of food insecurity Nguru Karasuwa Guzamala Bade Borsari Mobbar Bade Geidam Nganzai Monguro Jakusko Marte Yobe Ngala Tarmuwa Magumeri Kala/ Fune Jere Mafa Balge Nangere Dikwa Damaturu Kaga Maiduguru Potiskum Konduga Bama Fika arrivals of IDPs put additional stress Gujba Borno Gwoza Phase 1: Minimal Gulani Damboa Ganye Biu Chibok Madagali Askira/Uba Kwaya Michika Kusar Hawul Hong Bayo Mubi North Shani Girie Mubi South Shelleng Maina on host communities. -

Ondo State Pocket Factfinder

INTRODUCTION Ondo is one of the six states that make up the South West geopolitical zone of Nigeria. It has interstate boundaries with Ekiti and Kogi states to the north, Edo State to the east, Delta State to the southeast, Osun State to the northwest and Ogun State to the southwest. The Gulf of Guinea lies to its south and its capital is Akure. ONDO: THE FACTS AND FIGURES Dubbed as the Sunshine State, Ondo, which was created on February 3, 1976, has a population of 3,441,024 persons (2006 census) distributed across 18 local councils within a land area of 14,788.723 Square Kilometres. Located in the South-West geo-political zone of Nigeria, Ondo State is bounded in the North by Ekiti/Kogi states; in the East by Edo State; in the West by Oyo and Ogun states, and in the South by the Atlantic Ocean. Ondo State is a multi-ethnic state with the majority being Yoruba while there are also the Ikale, Ilaje, Arogbo and Akpoi, who are of Ijaw extraction and inhabit the riverine areas of the state. The state plays host to 880 public primary schools, and 190 public secondary schools and a number of tertiary institutions including the Federal University of Technology, Akure, Ondo State Polytechnic, Owo, Federal College of Agriculture, Akure and Adeyemi College of Education, Ondo. Arguably, Ondo is one of the most resource-endowed states of Nigeria. It is agriculturally rich with agriculture contributing about 75 per cent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The main revenue yielding crops are cocoa, palm produce and timber. -

Drought Occurrences and Its Implications on the Households in Yobe State, Nigeria Jude Nwafor Eze

Eze Geoenvironmental Disasters (2018) 5:18 Geoenvironmental Disasters https://doi.org/10.1186/s40677-018-0111-7 RESEARCH Open Access Drought occurrences and its implications on the households in Yobe state, Nigeria Jude Nwafor Eze Abstract The study assesses the extent of droughts and its implications on the households in the study area. This is to highlight the need to integrate drought adaptation options into the government development plans. Strategies for drought adaptation options in the study area have often been made without experimental foundations placed on the extent of drought and its implications on the households. To achieve this, the study employed Normalized Rainfall Index (NRI) to determine the extent of droughts and its implications on the households, which has much to offer in terms of policy decisions. The study also utilized questionnaire administrated to 400 households to determine the annual income from different occupations that yielded more income to the people in the study area using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The NRI shows that the study area was characterized by mild to severe drought events. The first (1986–1995) and third (2006–2017) decades experienced high incidences of droughts, while the second decade (1996–2005), witnessed the least incidences of droughts. The result of the economic activities of the households reveals that 65% of the total household respondents were involved in farming, while 35% were involved in non-farming activities as their major source of livelihood. The analysis of variance on the economic activities that generated more income to the households in Yobe State shows that farming activities provided more opportunities for income generation. -

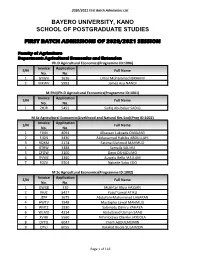

First Batch Admissions of 2020/2021 Session

2020/2021 First Batch Admissions List BAYERO UNIVERSITY, KANO SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES FIRST BATCH ADMISSIONS OF 2020/2021 SESSION Faculty of Agriculture Department: Agricultural Economics and Extension Ph.D Agricultural Economics(Programme ID:1006) Invoice Application S/N Full Name No. No. 1 GYWH 1636 Umar Muhammad IBRAHIM 2 MXWV 5993 James Asu NANDI M.Phil/Ph.D Agricultural Economics(Programme ID:1001) Invoice Application S/N Full Name No. No. 1 ZHJR 5491 Sadiq Abubakar SADIQ M.Sc Agricultural Economics(Livelihood and Natural Res Eco)(Prog ID:1002) Invoice Application S/N Full Name No. No. 1 FJVN 4091 Alhassan Lukpada DANLAMI 2 FJQN 3430 Abdussamad Habibu ABDULLAHI 3 RQXM 2174 Fatima Mahmud MAHMUD 4 BTRW 3488 Samaila SALIHU 5 CFQW 3100 Dayo OSHADUMO 6 RVWZ 3360 Auwalu Bello MALLAM 7 FDZV 5504 Ngbede Sabo EDO M.Sc Agricultural Economics(Programme ID:1002) Invoice Application S/N Full Name No. No. 1 QWXB 330 Mukhtar Aliyu HASSAN 2 XHJC 5427 Yusuf Lawal ATIKU 3 JZFP 1675 Abdullahi Muhammad LABARAN 4 HWTV 1948 Mustapha Lawal MAHMUD 5 RMTZ 1930 Salamatu Dahiru YAHAYA 6 WLMD 4314 Abdulbasid Usman SAAD 7 XVHK 5560 Nihinlolawa Olanike JAYEOLA 8 DYTQ 6047 Imam ABDULMUMIN 9 CPVJ 6055 Barakat Bisola SULAIMON Page 1 of 116 2020/2021 First Batch Admissions List M.Sc Agricultural Extension(Programme ID:1003) Invoice Application S/N Full Name No. No. 1 DMWZ 36 Olayinka Adebola BELLO 2 PYHF 518 Isiagu Benedeth ANTHONY 3 RVFW 2291 Obako ENAHIBRAHIM 4 XFYN 2366 Kabiru MUSA 5 HBYD 5171 Musa GARBA Department: Agronomy Ph.D Agronomy(Programme ID:1108) Invoice Application S/N Full Name No. -

Power Grid Corridor Modelling for Efficient Electricity Distribution in Communities of Damaturu Nigeria Using GIS

International Journal of Advances in Scientific Research and Engineering (ijasre) E-ISSN : 2454-8006 DOI: 10.31695/IJASRE.2019.33154 Volume 5, Issue 4 April - 2019 Power Grid Corridor Modelling for Efficient Electricity Distribution in Communities of Damaturu Nigeria Using GIS Bala-Geidam M.1, Badema A.2 and Shuaibu, M. A.3 1Dept. of Basic Science, Yobe State College of Agriculture Gujba, Yobe State Nigeria 2Dept. of Geography, Yobe State University Damaturu, Yobe State, Nigeria 3Dept. of Surveying and Geoinformatics, Abubakar TafawaBalewa University Bauchi Nigeria _______________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT This study focused on modelling of power grid corridor using geographic information system (GIS). The objectives are to map and evaluate the communities and existing Substations on national Grid with the aim of modelling new substations source for effective power distribution in the study area. The mapping of positions of the substations and communities around the grid was achieved using Etrex 10 handheld GPS receiver and the evaluation was carried out using the Location allocation analysis of ArcGIS 10.3. The result of the model reveals that ten (10) out of the thirty-two (32) communities found were on the national grid while eight (8) distribution substations out of the ten (10) communities were discovered during location-allocation analysis. Consequently, the pattern of distribution of the substations was found to be random but optimal and least cost. Hence, the result of this study will certainly make electricity distribution efficient in the study area and hence recommended for use by all stakeholders. KEY WORDS: Modelling, Location Allocation Analysis, GIS, Power Grid. ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. -

Unimaid Utme 2016 2017 First Batch

UNIVERSITY OF MAIDUGURI (OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR) UTME ADMISSION 2016/2017 SESSION COLLEGE OF MEDICINE MBBS S/No. REGISTRATION No. NAME 1 65012453FG PAUL LIZZY-ROSE OILONYE 2 65241316DD THOMAS TIMOTHY CHINDA 3 65988663FA HARUNA USMAN 4 65880541EI IBRAHIM KUBAIDU 5 66531268IJ UDECHUKWU FRANKLYN CHUKWUEMEKA 6 65305578ID DAUDA ADAMU ADAMU 7 66546199BD MUKTAR USMAN MODIBBO 8 65989125CC ADEBAYO ABRAHAM SUNDAY OMEIZA 9 65759941DI ORLU-OMA CHIMELE 10 65021759HE AKIN VICTOR SAMARI 11 65488101HJ LUKA SHELLE 12 65859958AI TERHEMBA JERRY SAANIYOL 13 65875581IH UMAR ABUBAKAR 14 65891180EE BUBA BASHIR A 15 65295774AH NUHU RHODA ALKALI 16 66546503HB ANDREW MELCHIZEDEK 17 66550295EE AHMAD SHAMSUDDEEN 18 65198536EC ECHE MOSES ALAJE 19 65904453JC OCHE PRINCESS EHI 1 20 65299718AJ ABDULMUMIN ABUBAKAR 21 65459752FH OBI SOMTO 22 65780434FH JATTO ISA ENERO 23 66200732GG MICHAEL BLESSING 24 66299464BB MICHAEL KISLON SHITNAN 25 65903857DH USMAN ADAMA 26 66215998FC GWASKI ISAAC DIKA 27 66496897JB MOHAMMED ADAMU DUMBULWA 28 65243376GB TAHIR MUHAMMAD ARABO 29 66048182HA JERRY LEAH 30 65885079BE AHMED ABBA 31 65858960JC GAMBO LAWI 32 66246168ED SAMAILA BITRUS VISION 33 65919477CI OBI PETER CHIGOZIE 34 65548790IB GADZAMA JANADA YOHANNA 35 66193123AB MOSES MATTHEW TAIYE 36 65780170HD AERNAN SEDOO 37 65786350GA ZAKARIYYA ABDULMUMIN SANI 38 66324429JH OJIMADU CHIDINDU GODSWILL 39 65527190IF MBAYA ENOCH SAMUEL 40 65199053ED GAGA TERNGUNAN ERIC 41 65534793HB ROBERT RAKEAL 42 65305105EH YAK'OR TONGRIYANG DAWEET 43 65299765GC GONI AISHA UMAR 44 65136595BD AFOLABI ABDULWAHAB -

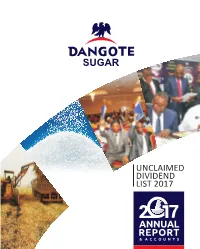

Dangote Sugar Divident 2017

UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND LIST 2017 ”Sugar for Nigeria” Project 7 ANNUAL REPORT & A C C O U N T S ANNUAL REPORT 7 & A C C O U N T S UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND LIST 2017 S/NO WARR NO SHAREHOLDER'S NAME S/NO WARR NO SHAREHOLDER'S NAME 1 12932 OKORIE HELEN OGOWUGO 88 24033 IYAMU JOHNSON CHUKWUEMEKE 2 23939 EZUMA INNOCENT 89 24148 MUSA SAABIYA ABUBAKAR 3 24809 ISHAQ HAMZA DANMAHAWAYI 90 24355 SHAIBU AL-HASSAN 4 29563 OMOLUMHEN JOHN 91 24422 USMAN AMINA 5 7937 MANTU NAZEEHATU ABDULLAHI 92 24432 UWEH NWABUEZE PATERSON 6 12718 IKOTUN MOSES OLADELE 93 24558 ANOSIKE MAXWELL 7 16745 AKINKUOLIE OLUWASINA HENRY 94 25183 EBIRERI JOHNSON OHWOBENO 8 23244 PREBOR AREREPADE 95 25330 NUHU HANAFIYA MOHAMMED 9 24957 SHEMAU AMINU OTHMAN 96 25499 LAWAL NASIRU SHARGALLE 10 24958 SHETTIMA AISHA KASHIM BUKAR 97 25516 SULEIMAN ZAINAB 11 24959 SHETTIMA AMEENA KOLO KASHIM BU KAR 98 26215 AJEIGBE OLAYINKA SAMUEL 12 26095 AGHANENU PATAICK 99 26223 AJIBADE AHMED LANRE 13 27214 DOMFA-LARS TI-TYEM ENOCH 100 26827 AZIKEN GEORGE UCHE 14 29667 ONOS PATRICK BUNOR 101 26922 BELL GAM IBIENE S 15 30372 SUNRISE MICRO-FINANCE BANK NIG LTD 102 27656 FATIMILEHIN OLUWATOBI 16 30601 USMAN AFOR JUDITH JULIET 103 28196 JOSHUA JOEY 17 30704 YUSSUF SULAIMAN IYANDA 104 28197 JOSHUA JONATHAN 18 31913 LAWAL FOLASADE 105 28210 KALLAMU MOSES TUKYES 19 28099 ISANGEDIGHI HENRIETTA 106 28619 NKEMKA CHUKWUEMEKA MOSES 20 29021 OGUNLEYE OLUWATOYIN ALABA 107 28644 NNOLI NNAMDI 21 25200 GARZALI SHUAIBU 108 28765 OBI APRIL UGONNA 22 24044 JIBO MOHAMMED UMARU 109 28941 OGBOGU MARGARET ADENIKE 23 23319 ASUELIMEN ANTHONY -

YOBE STATE MINISTRY of HEALTH Situation Report

YOBE STATE MINISTRY OF HEALTH Situation Report TITLE COVID-19 Pandemic Situation Report SERIAL NUMBER 17 EPID-WEEK 20 DATE 16 May 2020 HIGHLIGHTS: No new confirmed case(s) reported today Fifty-one (51) new contacts of the confirmed cases have been identified and line-listed by the contact tracing teams SMOH and WHO recruited, trained and deployed six (6) additional contact tracing teams in Gujba, Nguru, and Tarmuwa LGAs Seven (7) new alerts have been received and investigated in Nguru, Potiskum and Gujba LGAs Conducted high-level advocacy, led by the Hon Commissioner for Health (Vice-Chairman of State Task Force) and other members of State Rapid Response Team (SRRT), to Bade LGA emirate council to sensitize traditional leaders and community members on prevention of COVID-19 in their communities. EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SUMMARY: The total number of confirmed COVID-19 cases remains thirty-two (32): Sixteen (16) cases from Damaturu, eight (8) cases from Bade, five (5) cases from Nguru, and one (1) case each from Geidam, Tarmuwa, and Gujba LGAs Total confirmed cases of COVID-19 amongst Health Care Workers (HCWs) in the state remain nine (9): Six (6) nurses, two (2) doctors, and one (1) laboratory scientist Twenty-four (24) confirmed cases are on admission in isolation centers. All are in stable condition Three (3) cases have recovered and discharged from the isolation center two days ago The total number of contacts who completed the 14-days follow-up as of today is one hundred and twenty-four (124). None of them developed any symptoms The total number of deaths due to COVID-19 in the state is five (5) The total number of samples taken for testing remains sixty-three (63). -

YOBE STATE MINISTRY of HEALTH Situation Report

YOBE STATE MINISTRY OF HEALTH Situation Report TITLE COVID-19 Pandemic Situation Report SERIAL NUMBER 15 EPID-WEEK 20 DATE 14 May 2020 HIGHLIGHTS: Twelve (12) new confirmed case(s) reported today: Six (6) cases from Bade LGA, three (3) cases from Damaturu, and one (1) case each from Nguru, Gujba, and Tarmuwa LGAs. Three (3) cases have been discharged from the State Specialist Hospital (SSH) Damaturu isolation center today Twenty-four (24) confirmed cases are on admission in isolation centers. All are in stable condition Six (6) new alerts have been received and investigated in Damaturu, Jakusko, Gashua, and Potiskum LGAs Twenty-five (25) contacts of the new confirmed cases have been identified and line-listed by the contact tracing teams. And they are being [closely] monitored. EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SUMMARY: The total number of confirmed COVID-19 cases is now thirty-two (32): Sixteen (16) cases from Damaturu, eight (8) cases from Bade, five (5) cases from Nguru, and one (1) case each from Geidam, Tarmuwa, and Gujba LGAs Total confirmed cases of COVID-19 amongst Health Care Workers (HCWs) in the state are nine (9): Six (6) nurses, two (2) doctors, and one (1) laboratory scientist. Twenty-four (24) confirmed cases are on admission in isolation centers. All are in stable condition Three (3) cases have been discharged from the State Specialist Hospital (SSH) Damaturu isolation center today Total number of deaths due to COVID-19 in the state is five (5) The total number of samples collected so far is sixty-three (63). Of these, thirty-two (32) returned positive, eighteen (18) are negative and the result of thirteen (13) remaining samples is being awaited.