Inquiry Student Cross-Cultural Field Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edition 3 | 2019-2020

A Message from the Chair of the Board of Trustees 4 2020 Musician Roster 5 JANUARY 10-12 9 Russian Winter Festival I: Natasha Returns JANUARY 24-25 17 Russian Winter Festival II: Masterpieces FEBRUARY 21-22 25 Saint-Saëns Organ Symphony With Cameron Carpenter FEBRUARY 28-29 33 Chihuly Festival: Bluebeard’s Castle Spotlight on Education 42 Board of Trustees/Staff 43 Friends of the Columbus Symphony 45 Columbus Symphony League 46 Future Inspired 47 Partners in Excellence 49 Corporate and Foundation Partners 49 Individual Partners 50 In Kind 53 Tribute Gifts 53 Legacy Society 56 Concert Hall & Ticket Information 58 ADVERTISING Onstage Publications 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 e-mail: [email protected] www.onstagepublications.com The Columbus Symphony program is published in association with Onstage Publications, 1612 Prosser Avenue, Dayton, Ohio 45409. The Columbus Symphony program may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher. Onstage Publications is a division of Just Business!, Inc. Contents © 2020. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Dear Columbus Symphony Supporter, As the wonderful performances of our 2019-20 season continue, we again thank you for your support of quality, live performances of orchestral music in our community! We start the new year by putting the star in Columbus with Russian Winter Festival I: Natasha Returns (January 10–12, Ohio Theatre). Natasha Paremski performs Rachmaninoff’s first piano concerto, and the concert concludes with the dramatic genius of Tchaikovsky in his powerful Manfred symphony. -

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto Friday, January 12, 2018 at 11 am Jayce Ogren, Guest conductor Sibelius Symphony No. 7 in C Major Tchaikovsky Concerto for Violin and Orchestra Gabriel Lefkowitz, violin Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto For Tchaikovsky and The Composers Sibelius, these works were departures from their previ- ous compositions. Both Jean Sibelius were composed in later pe- (1865—1957) riods in these composers’ lives and both were pushing Johan Christian Julius (Jean) Sibelius their comfort levels. was born on December 8, 1865 in Hämeenlinna, Finland. His father (a doctor) died when Jean For Tchaikovsky, the was three. After his father’s death, the family Violin Concerto came on had to live with a variety of relatives and it was Jean’s aunt who taught him to read music and the heels of his “year of play the piano. In his teen years, Jean learned the hell” that included his disas- violin and was a quick study. He formed a trio trous marriage. It was also with his sister older Linda (piano) and his younger brother Christian (cello) and also start- the only concerto he would ed composing, primarily for family. When Jean write for the violin. was ready to attend university, most of his fami- Jean Sibelius ly (Christian stayed behind) moved to Helsinki For Sibelius, his final where Jean enrolled in law symphony became a chal- school but also took classes at the Helsinksi Music In- stitute. Sibelius quickly became known as a skilled vio- lenge to synthesize the tra- linist as well as composer. He then spent the next few ditional symphonic form years in Berlin and Vienna gaining more experience as a composer and upon his return to Helsinki in 1892, he with a tone poem. -

Prokofiev Shostakovich Tchaikovsky

Prokofiev £3 Shostakovich Tchaikovsky PROGRAMME MICHAEL FOYLE VIOLIN MIHAI RITIVOIU PIANO MICHAEL COLLINS CONDUCTOR WEDNESDAY ENGLISH 16TH MAY CHAMBER 7.30PM ORCHESTRA CADOGAN HALL Programme welcome Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 1 in D major Shostakovich Piano Concerto No. 2 in F major Welcome to the Cadogan Chekhov or Tolstoy in our Hall for what I am sure theatres or an exhibition will be a thrilling evening, such as that which has combining one of the just finished at the Royal Interval world’s great chamber Academy. We celebrate orchestras with two brilliant this amidst the turmoil young soloists and the of international relations. Tchaikovsky well-established conductor/ clarinettist Michael Collins. Thank you to the several Symphony No. 4 in F minor groups who are supporting We are celebrating three this event – not least the ‘debuts’ this evening. International Business Mihai Ritivoiu piano Michael has been a soloist and Diplomatic Exchange Michael Foyle violin with the English Chamber (IBDE) whose advisory Orchestra and tonight board I have the privilege Michael Collins conductor conducts them for the to chair, and the first time. And CMF artists, City Music Foundation. violinist Michael Foyle English Chamber Orchestra and pianist Mihai Ritivoiu May I also express our Sir Roger Gifford play with the ECO for the grateful thanks to an English Chamber Orchestra first time in their rapidly anonymous donor and Music Society developing careers. and the members of Founder, City Music Foundation Winckworth Sherwood LLP The music tonight reflects for their assistance in the the enormous contribution conception and promotion made by Russian arts to of this event. -

Read the Program

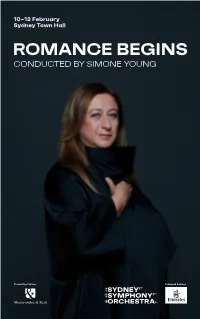

10–13 February Sydney Town Hall ROMANCE BEGINS CONDUCTED BY SIMONE YOUNG Presenting Partner Principal Partner 2021 CONCERT SEASON Wednesday 10 February, 8pm SYDNEY SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ABERCROMBIE & KENT MASTERS SERIES Thursday 11 February, 7pm Friday 12 February, 8pm Saturday 13 February, 8pm PATRON Her Excellency The Honourable Margaret Beazley AC QC Sydney Town Hall Founded in 1932 by the Australian Broadcasting Commission, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra has evolved into one of the world’s finest orchestras as Sydney has become one of the world’s great cities. Resident at the iconic Sydney Opera House, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra also performs in venues throughout Sydney and regional New South Wales, and international tours to Europe, Asia and the USA have earned the Orchestra worldwide recognition for artistic excellence. The Orchestra’s first chief conductor was Sir Eugene Goossens, appointed in 1947; ROMANCE he was followed by Nicolai Malko, Dean Dixon, Moshe Atzmon, Willem van Otterloo, Louis Frémaux, Sir Charles Mackerras, Zdenêk Mácal, Stuart Challender, Edo de Waart and Gianluigi Gelmetti. Vladimir Ashkenazy was Principal Conductor from BEGINS 2009 to 2013, followed by David Robertson as Chief Conductor from 2014 to 2019. CONDUCTED BY SIMONE YOUNG Australia-born Simone Young has been the Orchestra’s Chief Conductor Designate since 2020. She commences her role as Chief Conductor in 2022 as the Orchestra returns to the renewed Concert Hall of the Sydney Opera House. The Sydney Symphony Orchestra's concerts encompass masterpieces from the classical repertoire, music by some of the finest living composers, and collaborations SIMONE YOUNG conductor ESTIMATED DURATIONS with guest artists from all genres, reflecting the Orchestra's versatility and diverse DANIEL RÖHN violin 33 minutes, interval 20 appeal. -

Manfred Symphony

PETER ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY MANFRED SYMPHONY Sit back and enjoy Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky The redemption of himself to this and to its eponymous The Manfred Symphony: an experienced before his death at only Manfred Symphony, Op. 58 hero with zeal, and seemed to unrestrained self-portrait 36 years of age, was enough to cover Manfred even somewhat transform himself Romantic poet surrounded by several lifetimes: inheriting a title 1. Lento lugubre – Moderato con moto – Andante 17.27 into Manfred during the intensive scandal and strife-torn hero – the at 10 years old, entering the House 2. Vivace con spirito 9.57 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Manfred is period of work. After all, he was literary model of Lords when he came of age; 3. Andante con moto 11.24 a hermaphrodite – at least, as far as also suffering from inner torment. Had George Gordon Noel Byron early travels to the Mediterranean 4. Allegro con fuoco 20.21 the music is concerned. For although And this can be heard in the music, lived in the present day, then the and further onwards to Asia Minor; the work (dating from 1885) was which appears to be full of inner abundant major and minor scandals instantaneous literary fame thanks 59.29 indeed dubbed by its creator as a conflict. Nowadays, Manfred that surrounded him would almost to Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage; social symphony, it still did not receive is rarely heard in the concert certainly have given the ever-hungry scandals following relationships a number alongside Tchaikovsky’s hall. Perhaps due to its rather tabloid press something to feast on. -

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto in D Major, Op

23 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, September 20, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, September 21, at 2:00 Saturday, September 22, Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor at 8:00 Lisa Batiashvili Violin Berwald Symphony No. 3 in C major (“Sinfonie singulière”) I. Allegro fuocoso II. Adagio III. Finale: Presto First Philadelphia Orchestra performances Sibelius Symphony No. 7, Op. 105 (In one movement) Intermission Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35 I. Allegro moderato—Moderato assai II. Canzonetta: Andante— III. Allegro vivacissimo This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. LiveNote® 2.0, the Orchestra’s interactive concert guide for mobile devices, will be enabled for these performances. The September 20 concert is sponsored by Mrs. Lyn M. Ross in memory of George M. Ross. The September 21 concert is sponsored by Edith R. Dixon. The September 22 concert is sponsored by David Haas. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. ® Getting Started with LiveNote 2.0 » Please silence your phone ringer. » Make sure you are connected to the internet via a Wi-Fi or cellular connection. » Download the Philadelphia Orchestra app from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store. » Once downloaded open the Philadelphia Orchestra app. » Select the LiveNote tab in the bottom left corner. » Tap “OPEN” on the Philadelphia Orchestra concert you are attending. » Tap the “LIVE” red circle. The app will now automatically advance slides as the live concert progresses. -

Season 2013-2014

23 Season 2013-2014 Thursday, January 23, at 8:00 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, January 24, at 8:00 Tugan Sokhiev Conductor Vadim Gluzman Violin Rimsky-Korsakov “Battle of Kerzhenets,” from The Legend of the Invisible City of Kitezh and the Maiden Fevroniya Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35 I. Allegro moderato—Moderato assai II. Canzonetta: Andante— III. Allegro vivacissimo Intermission Musorgsky/ Pictures from an Exhibition orch. Ravel Promenade— I. Gnomus Promenade— II. The Old Castle Promenade— III. Tuileries IV. Bydlo Promenade— V. Ballet of the Chicks in their Shells VI. “Samuel” Goldenberg and “Schmuÿle” VII. Limoges: The Market— VIII. Catacombs: Sepulcrum romanum—Cum mortuis in lingua mortua IX. The Hut on Fowl’s Legs (Baba Yaga)— X. The Great Gate at Kiev This program runs approximately 1 hour, 40 minutes. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 224 Story Title The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra community itself. His concerts to perform in China, in 1973 is one of the preeminent of diverse repertoire attract at the request of President orchestras in the world, sold-out houses, and he has Nixon, today The Philadelphia renowned for its distinctive established a regular forum Orchestra boasts a new sound, desired for its for connecting with concert- partnership with the National keen ability to capture the goers through Post-Concert Centre for the Performing hearts and imaginations of Conversations. Arts in Beijing. The Orchestra audiences, and admired for annually performs at Under Yannick’s leadership a legacy of innovation in Carnegie Hall while also the Orchestra returns to music-making. -

P. I. Tchaikovsky Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 35

P. I. Tchaikovsky Concerto for violin and orchestra, op. 35 By Marina Popovic Supervisor Per Kjetil Farstad This Master’s Thesis is carried out as a part of the education at the University of Agder and is therefore approved as a part of this education. However, this does not imply that the University answers for the methods that are used or the conclusions that are drawn. University of Agder, 2012 Faculty of Fine Arts Department of Music 2 Acknowledgments I have to admit that studying in Norway was tough occasionally, but I fill the need to express special thanks to persons that made it much possible. I use this opportunity to thank my parents for the longest support in my carrier. Even though I owe gratitude to all my teachers and professors; special thanks go to my professors at University of Agder: Per Kjetil Farstad, Tønsberg, Knut, Adam Grüchot, Terje Howard Mathisen, Tellef Juva, Bård Monsen and Trygve Trædal. Also, I want to express thankfulness to my fellow students Rade Zivanovic, Jelena Adamovic, Stevan Sretenovic, Nikola Markovic, Svetlana Jelic and Andrej Miletic for both critics and support during our mutual work. Last, but of the significant importance my acknowledgment goes to libraries of University of Agder and Faculty of Music, Belgrade. 3 Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 3 Contents .............................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction -

Tchaikovsky Research Bulletin No. 1

"Klin, near Moscow, was the home of one of the busiest of men…" Previously unknown or unidentified letters by Tchaikovsky to correspondents from Russia, Europe and the USA Presented by Luis Sundkvist and Brett Langston Contents Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 2 I. Russia (Milii Balakirev, Adolph Brodsky, Mariia Klimentova-Muromtseva, Ekaterina Laroche, Iurii Messer, Vasilii Sapel'nikov) .. .. .. 5 II. Austria (Anton Door, Albert Gutmann) .. .. .. .. .. 15 III. Belgium (Désirée Artôt-Padilla, Joseph Dupont, Jean-Théodore Radoux, Józef Wieniawski) .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 19 IV. Czech Republic (Adolf Čech, unidentified) .. .. .. .. .. 25 V. France (Édouard Colonne, Eugénie Vergin Colonne, Louis Diémer, Louis Gallet, Lucien Guitry, Jules Massenet, Pauline Viardot-García, three unidentified) .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 29 VI. Germany (Robert Bignell, Hugo Bock, Hans von Bülow, Paul Cossmann, Mathilde Cossmann, Aline Friede, Julius Laube, Sophie Menter, Selma Rahter, Friedrich Sieger, two unidentified) .. .. .. .. 55 VII. Great Britain (George Bainton, George Henschel, Francis Arthur Jones, Ethel Smyth, unidentified) .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 69 VIII. Poland (Édouard Bergson, unidentified) .. .. .. .. .. 85 IX. United States (E. Elias, W.S.B. Mathews, Marie Reno) .. .. .. 89 New locations for previously published letters .. .. .. .. .. 95 Chronological list of the 55 letters by Tchaikovsky presented in this article .. 96 Acknowledgements .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. 101 Introduction Apart from their authorship, the only thing that most of the -

The History of Tchaikovsky's Variations on a Rococo Theme and The

THE HISTORY OF TCHAIKOVSKY’S VARIATIONS ON A ROCOCO THEME AND THE COLLABORATION WITH FITZENHAGEN Table of Contents • Introduction • Revisiting the Variations’ history: • a chronology of the editorial and critical correspondence • The Variations in the context of their title and style • Conclusion • APPENDIX I • APPENDIX II • Endnotes Sergei Istomin Sergei Istomin is in demand as soloist and chamber musician, with an extensive recording career. His repertoire includes baroque, classical, romantic and contemporary music on both period and modern instruments. Istomin currently teaches viola da gamba and violoncello at the Ghent Conservatory (KASK) in Belgium. by Sergei Istomin Music & Practice, Volume 4 Scientific Introduction Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Variations on a Rococo theme, op. 33, were dedicated to the cellist Karl Friedrich Wilhelm Fitzenhagen, who premiered this masterpiece in Moscow in 1877.[1]Fitzenhagen’s role in the compositional process has frequently been discussed by musicologists and performance practice specialists. In this article, we aim to re-assess Fitzenhagen’s involvement with the Variations with regard to ‘Texttreue’ – in other words, the performer’s fidelity to the text of a work – and re-evaluate Fitzenhagen’s own arrangement of the Variations with regard to the most recent musicological publications.[2] In the field of today’s performance practice, our task is to shine a much-needed light on Fitzenhagen’s contribution to the Variations’ editorial and publishing processes. In the first part of this article, the chronological history of the editorial and critical correspondence in the history of the Variations will be treated in detail. The two distinct versions of the Variations, which co-exist already in the original manuscripts, are of central significance to the subject matter. -

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

May 5 Program Notes: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky following his own path by blending discovery of Édouard Lalo’s violin- steps back from the emotional (1840-1893) national Russian elements with centric Symphonie espagnole (much turbulence and soul-searching techniques and forms he learned from as his enthusiasm for Carmen, which attitude of the contemporaneous Concerto for Violin in D Western tradition. While the Mighty he encountered in 1876, left its Fourth Symphony, though it exhibits major, Op. 35 Five prized do-it-yourselfness and mark on the Fourth Symphony). an extroverted theatricality of its scorned professional What Tchaikovsky admired in the own. Born on May 7, 1840, in Votkinsk, training, Tchaikovsky attended Lalo piece, he wrote, was the focus Russia; died on November 6, 1893, in St. Tchaikovsky integrates a considerable the conservatory and began to prepare on “musical beauty” instead of the Petersburg, Russia. arsenal of technical challenges for routines of “established traditions.” his career methodically. the soloist with a juicy, unhurried Tchaikovsky composed the Violin Concerto But all his careful planning could As it happened, the young violinist lyricism that somehow also manages in 1878. First performance: December 4, not have prepared the composer for who brought Lalo’s score to his to touch on the epic. Although darker 1881, in Vienna, with Adolph Brodsky as the events of 1877 and the turmoil they attention, a recent student of undercurrents occasionally intrude, the soloist and Hans Richter conducting. In would cause. Tchaikovsky named Iosif Kotek, the stereotype of the hyper-emotive, addition to solo violin, Tchaikovsky’s Violin provided a further impetus. -

Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto in D Major

“Inside Masterworks” Be Transformed MARCH 2016 Masterworks #6: Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto in D Major: An emotional drama that gave birth to a masterpiece. In the early winter of 1877, 37-year old Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was found neck-deep in the icy water of the River Neva, trying to commit suicide by freezing himself to death. Just months earlier, Tchaikovsky had married Antonina Milyukova but, in truth, the marriage was doomed before it began. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Letters to his younger brother Modest in late 1876 and marriage, Tchaikovsky made an unsuccessful suicide early 1877 revealed Tchaikovsky’s ambivalent feelings attempt in the icy river and fled Moscow. i on the subject of his sexuality and marriage. The letters referenced three recent homosexual encounters and a In early 1878, Tchaikovsky was with Kotek in v growing passionate love for Iosif Kotek, his student from Switzerland, recovering from his emotional breakdown. the Moscow Conservatory. Writing of his deep love for At Kotek’s urging, Kotek, Tchaikovsky’s described his emotional pull to Iosif Tchaikovsky began as an “unimaginable force”: composing the Violin Concerto, and quickly “My only need is for him to know that I love him became so carried away endlessly... It is impossible for me to hide my that he abandoned work feelings for him, although I tried hard to do so on his Grand Sonata, at first. Yesterday I made a total confession of love, which was already in ii vi begging him not to be angry…” progress. Kotek assisted Tchaikovsky, playing By the Spring of 1877, Tchaikovsky’s intense infatuation portions to iron out details with Kotek had cooled, but they remained devotedly close while offering his own vii friends.