Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waltz from the Sleeping Beauty

Teacher Workbook TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from Jessica Nalbone .................................................................................2 Director of Education, North Carolina Symphony Information about the 2012/13 Education Concert Program ............................3 North Carolina Symphony Education Programs .................................................4 Author Biographies ..............................................................................................6 Carl Nielsen (1865-1931) .......................................................................................7 Oriental Festival March from Aladdin Suite, Op. 34 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) ..........................................................15 Symphony No. 39 in E-flat Major, K.543, Mvt. I or III (Movements will alternate throughout season) Claude Debussy (1862-1918) ..............................................................................28 “Golliwogg’s Cakewalk” from Children’s Corner, Suite for Orchestra Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893) ..................................................................33 Waltz from The Sleeping Beauty Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) ...............................................................................44 “Dance of the Young Girls” from The Rite of Spring Loonis McGlohon (1921-2002) & Charles Kuralt (1924-1997) ..........................52 “North Carolina Is My Home” Richard Wagner (1813-1883) ..............................................................................61 Overture to Rienzi -

The Transformation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin Into Tchaikovsky's Opera

THE TRANSFORMATION OF PUSHKIN'S EUGENE ONEGIN INTO TCHAIKOVSKY'S OPERA Molly C. Doran A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Megan Rancier © 2012 Molly Doran All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Since receiving its first performance in 1879, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s fifth opera, Eugene Onegin (1877-1878), has garnered much attention from both music scholars and prominent figures in Russian literature. Despite its largely enthusiastic reception in musical circles, it almost immediately became the target of negative criticism by Russian authors who viewed the opera as a trivial and overly romanticized embarrassment to Pushkin’s novel. Criticism of the opera often revolves around the fact that the novel’s most significant feature—its self-conscious narrator—does not exist in the opera, thus completely changing one of the story’s defining attributes. Scholarship in defense of the opera began to appear in abundance during the 1990s with the work of Alexander Poznansky, Caryl Emerson, Byron Nelson, and Richard Taruskin. These authors have all sought to demonstrate that the opera stands as more than a work of overly personalized emotionalism. In my thesis I review the relationship between the novel and the opera in greater depth by explaining what distinguishes the two works from each other, but also by looking further into the argument that Tchaikovsky’s music represents the novel well by cleverly incorporating ironic elements as a means of capturing the literary narrator’s sardonic voice. -

Tchaikovsky Caprice Italien - "Eugene Onegin": Introduction & Waltz and Polonaise - Theme and Variations from Suite No

Tchaikovsky Caprice Italien - "Eugene Onegin": Introduction & Waltz And Polonaise - Theme And Variations From Suite No. 3 In G mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Caprice Italien - "Eugene Onegin": Introduction & Waltz And Polonaise - Theme And Variations From Suite No. 3 In G Country: UK Released: 1961 MP3 version RAR size: 1418 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1935 mb WMA version RAR size: 1899 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 172 Other Formats: MP1 VOC ASF MOD AA AU DTS Tracklist A1 Caprice Italien, Op. 45 A2 Introduction And Waltz (From Eugene Onegin, Act 2) B1 Polonaise (From Eugene Onegin, Act 3) B2 Theme And Variations (From Suite No. 3 In G Major, Op. 55) Companies, etc. Record Company – E.M.I. Records Limited Printed By – Garrod & Lofthouse Credits Composed By – Tchaikovsky* Conductor – Lovro Von Matacic Notes Recorded in co-operation with "E. A. Teatro alla Scala, Milan" Title on Spine "Caprice Italien etc." Title on Coverfront: "In collaboazione con l'ente autonomo del Teatro alla Scala - Tchaikovsky - Caprice Italien - Introduction And Waltz from "Eugene Onegin" - Polonaise from "Eugene Onegin" - Theme And Variations from Suite No.3 in G Major" Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Tchaikovsky*, The Orchestra Of La Scala, Tchaikovsky*, The Milan*, Lovro Von Matacic Orchestra Of La SAX 2418, - Caprice Italien - "Eugene Columbia, SAX 2418, Scala, Milan*, UK 1961 33CX 1772 Onegin": Introduction & Columbia 33CX 1772 Lovro Von Waltz And Polonaise - Matacic Theme And Variations From Suite No. 3 In G (LP) Related Music albums to Caprice Italien - "Eugene Onegin": Introduction & Waltz And Polonaise - Theme And Variations From Suite No. -

Download This Composer Profile Here

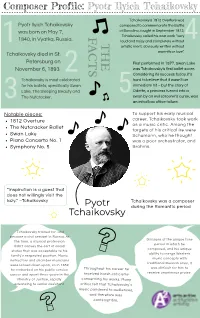

Composer Profile: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture was Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky composed to commemorate the Battle was born on May 7, of Borodino, fought in September 1812, F Tchaikovsky called his own work “very 1840, in Vyatka, Russia. loud and noisy and completely without THE A 4 1 artistic merit, obviously written without Tchaikovsky died in St. CTS warmth or love”. Petersburg on First performed in 1877, Swan Lake November 6, 1893. was Tchaikovsky’s first ballet score. 2 Considering its success today, it's Tchaikovsky is most celebrated hard to believe that it wasn’t an for his ballets, specifically Swan immediate hit – but the story of Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and Odette, a princess turned into a The Nutcracker. 5 swan by an evil sorcerer's curse, was 3 an initial box office failure. Notable pieces: To support his early musical 1812 Overture career, Tchaikovsky took work as a music critic. Among the The Nutcracker Ballet targets of his critical ire were Swan Lake Schumann, who he thought Piano Concerto No. 1 was a poor orchestrator, and Symphony No. 5 Brahms. “Inspiration is a guest that does not willingly visit the lazy.” –Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky was a composer I'mPy oOtrne! during the Romantic period Tchaikovsky Tchaikovsky trained for, and became a civil servant in Russia. At Because of the unique time the time, a musical profession period in which he didn’t convey the sort of social composed, and his unique status that was acceptable to his ability to merge Western family’s respected position. Music music concepts with instructors and chamber musicians traditional Russian ones, it were looked down upon, so in 1859 was difficult for him to he embarked on his public service Throughout his career he receive unanimous praise. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

Alexander Glazunov

Call & Response 2011 Music With Exotic Influences Glazunov, Schulhoff, Bloch, Debussy & Jeffery Cotton Listener’s Guide Join us for a performance of music inspired by the Exotic Call & Response 2011 Concert May 5, 2011, Herbst Theatre, San Francisco Details inside… Call & Response 2011: Music with exotic influences Concert Thursday, May 5, 2011 Herbst Theatre at the San Francisco War Memorial 401 Van Ness Avenue at McAllister Street San Francisco, CA 7:15pm Pre-Performance Lecture by composer Jeffery Cotton 8:00pm Performance Buy tickets online at: www.cityboxoffice .com or by calling City Box Office: 415-392-4400 Page Contents 3 The Concept: evolution of music over time and across cultures 4 Jeffery Cotton 6 Alexander Glazunov 8 Erwin Schulhoff 10 Ernest Bloch 12 Claude Debussy 2 Call & Response: The Concept Have you ever wondered how composers, modern composers at that, come up with their ideas? How do composers and other artists create new work? Our Call & Response program was born out of the Cypress String Quartet’s commitment to sharing with you and your community this process in music and all kinds of other artwork. We present newly created music based on earlier composed pieces. Why “Call & Response”? We usually associate the term “call & response” with jazz and gospel music, the idea being that the musician plays a musical “call” to which another musician “responds,”—a way of creating a new sound relating in some way to the original. In this program, the “call” is that of Cypress String Quartet searching for connections across musical, historical, and social boundaries. -

Rachmaninoff's Early Piano Works and the Traces of Chopin's Influence

Rachmaninoff’s Early Piano works and the Traces of Chopin’s Influence: The Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 & The Moments Musicaux, Op.16 A document submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Division of Keyboard Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music by Sanghie Lee P.D., Indiana University, 2011 B.M., M.M., Yonsei University, Korea, 2007 Committee Chair: Jonathan Kregor, Ph.D. Abstract This document examines two of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s early piano works, Morceaux de Fantaisie, Op.3 (1892) and Moments Musicaux, Opus 16 (1896), as they relate to the piano works of Frédéric Chopin. The five short pieces that comprise Morceaux de Fantaisie and the six Moments Musicaux are reminiscent of many of Chopin’s piano works; even as the sets broadly build on his character genres such as the nocturne, barcarolle, etude, prelude, waltz, and berceuse, they also frequently are modeled on or reference specific Chopin pieces. This document identifies how Rachmaninoff’s sets specifically and generally show the influence of Chopin’s style and works, while exploring how Rachmaninoff used Chopin’s models to create and present his unique compositional identity. Through this investigation, performers can better understand Chopin’s influence on Rachmaninoff’s piano works, and therefore improve their interpretations of his music. ii Copyright © 2018 by Sanghie Lee All rights reserved iii Acknowledgements I cannot express my heartfelt gratitude enough to my dear teacher James Tocco, who gave me devoted guidance and inspirational teaching for years. -

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director

PROGRAM ONE HUNDRED TWENTY-FOURTH SEASON Chicago Symphony Orchestra Riccardo Muti Zell Music Director Pierre Boulez Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo Ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, October 2, 2014, at 8:00 Friday, October 3, 2014, at 1:30 Saturday, October 4, 2014, at 8:30 Riccardo Muti Conductor Christopher Martin Trumpet Panufnik Concerto in modo antico (In one movement) CHRISTOPHER MARTIN First Chicago Symphony Orchestra performances Performed in honor of the centennial of Panufnik’s birth Stravinsky Suite from The Firebird Introduction and Dance of the Firebird Dance of the Princesses Infernal Dance of King Kashchei Berceuse— Finale INTERMISSION Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 3 in D Major, Op. 29 (Polish) Introduction and Allegro—Moderato assai (Tempo marcia funebre) Alla tedesca: Allegro moderato e semplice Andante elegiaco Scherzo: Allegro vivo Finale: Allegro con fuoco (Tempo di polacca) The performance of Panufnik’s Concerto in modo antico is generously supported by the Adam Mickiewicz Institute as part of the Polska Music program. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher Andrzej Panufnik Born September 24, 1914, Warsaw, Poland. Died October 27, 1991, London, England. Concerto in modo antico This music grew out of opus 1.” After graduation from the conserva- Andrzej Panufnik’s tory in 1936, Panufnik continued his studies in response to the rebirth of Vienna—he was eager to hear the works of the Warsaw, his birthplace, Second Viennese School there, but found to his which had been devas- dismay that not one work by Schoenberg, Berg, tated during the uprising or Webern was played during his first year in at the end of the Second the city—and then in Paris and London. -

4802170-Ccf435-053479213624.Pdf

1 Suite for Viola and Piano, Op. 8 - Varvara Gaigerova (1903-1944) 1. I. Allegro agitato 2:36 2. II. Andantino 3:06 3. III. Scherzo: Prest 4:25 4. IV. Moderato 4:47 Two Pieces for Viola and Piano, Op.31 - Alexander Winkler (1865-1935) 5. I. Méditation élégiaque (Andante mesto poco mosso) 4:22 6. II. La toupie: scène d’enfant: Scherzino (Allegro vivace) 2:44 Sonata in D Major for Viola and Piano, Op. 15 - Paul Juon (1872-1940) 7. I. Moderato 7:09 8. II. Adagio assai e molto cantabile 6:13 9. III. Allegro moderato 6:50 Sonata in C minor for Viola and Piano, Op. 10 - Alexander Winkler (1865-1935) 10. Moderato 9:59 11. Allegro agitato 6:28 12. L’istesso tempo ma poco rubato 4:24 Variations sur un air breton 13. Thème: Andante 1:06 14. Variation 1: L’istesso tempo poco rubato 1:39 15. Variation 2: Allegretto 1:06 16. Variation 3: Allegro patetico 1:10 17. Variation 4: Andante molto espressivo 1:23 18. Variation 5: Allegro con fuoco 1:18 19. Variation 6: Andante sostenuto 1:47 1 20. Variation 7: Fuga (Allegro moderato) 1:50 21. Coda: Poco più animato - Maestoso pesante 1:05 Total Time 71:02 In the early 20th century, composers Varvara Gaigerova, Alexander Winkler, and Paul Juon, reflect different aspects of Russian music at this historic time of intense social and political revolution. The Russian Revolution of 1905, the February and October Revolutions of 1917, in concert with the complex dynamics involved in the two great World Wars, created instability and hardship for most. -

Tchaikovsky.Pdf

Tchaikovsky CD 1 1 Orchestrion It wasn’t unusual, in the middle of the 19th century, to hear sounds like that coming from the drawing rooms of comfortable, middle-class families. The Orchestrion, one of the first and grandest of mass-produced mechanical music-makers, was one of the precursors of the 20th century gramophone. It brought music into homes where otherwise it might never have been heard, except through the stumbling fingers of children, enduring, or in some cases actually enjoying, their obligatory half-hour of practice time. In most families the Orchestrion was a source of pleasure. But in one Russian household, it seems to have been rather more. It afforded a small boy named Piotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky some of his earliest glimpses into a world, and a language, which was to become (in more senses then one), his lifeline. One evening his French governess, Fanny Dürbach, went into the nursery and found the tiny child sitting up in bed, crying. ‘What’s the matter?’ she asked – and his answer surprised her. ‘This music’ he wailed, ‘this music!’ She listened. The house was quiet. ‘No. It’s here,’ cried the boy – he pointed to his head. ‘It’s here, and I can’t make it go away. It won’t leave me.’ And of course it never did. ‘His sensitivity knew no bounds and so one had to deal with him very carefully. Every little trifle could upset or wound him. He was a child of glass. As for reproofs and admonitions (with him there could be no question of punishments), what would have been water off a duck’s back to other children affected him deeply, and if the degree of severity was increased only the slightest, it would upset him alarmingly.’ Despite his outwardly happy appearance, peace of mind is something Tchaikovsky rarely knew, from childhood to his dying day. -

Nikolai Tcherepnin UNDER the CANOPY of MY LIFE Artistic, Creative, Musical Pedagogy, Public and Private

Nikolai Tcherepnin UNDER THE CANOPY OF MY LIFE Artistic, creative, musical pedagogy, public and private Translated by John Ranck But1 you are getting old, pick Flowers, growing on the graves And with them renew your heart. Nekrasov2 And ethereally brightening-within-me Beloved shadows arose in the Argentine mist Balmont3 The Tcherepnins are from the vicinity of Izborsk, an ancient Russian town in the Pskov province. If I remember correctly, my aged aunts lived on an estate there which had been passed down to them by their fathers and grandfathers. Our lineage is not of the old aristocracy, and judging by excerpts from the book of Records of the Nobility of the Pskov province, the first mention of the family appears only in the early 19th century. I was born on May 3, 1873 in St. Petersburg. My father, a doctor, was lively and very gifted. His large practice drew from all social strata and included literary luminaries with whom he collaborated as medical consultant for the gazette, “The Voice” that was published by Kraevsky.4 Some of the leading writers and poets of the day were among its editors. It was my father’s sorrowful duty to serve as Dostoevsky’s doctor during the writer’s last illness. Social activities also played a large role in my father’s life. He was an active participant in various medical societies and frequently served as chairman. He also counted among his patients several leading musical and theatrical figures. My father was introduced to the “Mussorgsky cult” at the hospitable “Tuesdays” that were hosted by his colleague, Dr.