On Huang Yong Ping 69 Ryan Holmberg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Travel Give Into Your Wanderlust 广告

广告 July 2020 Plus: A Beijing Family Scavenger Hunt Insider Knowledge: Put Your Trust in Beijing’s Best Local Tour Guides and Really Explore The City You Call Home Travel Give Into Your Wanderlust 广告 July 2020 Plus: A Beijing Family Scavenger Hunt Insider Knowledge: Put Your Trust in Beijing’s Best Local Tour Guides and Really Explore The City You Call Home Travel Give Into Your Wanderlust WOMEN OF CHINA WOMEN July 2020 PRICE: RMB¥10.00 US$10 Plus: A Beijing Family Scavenger O Hunt 《中国妇女》 Insider Knowledge: Put Your Trust in Beijing’s Beijing’s essential international family resource resource family international essential Beijing’s Best Local Tour Guides and Really Explore The City You Call Home 国际标准刊号:ISSN 1000-9388 国内统一刊号:CN 11-1704/C July 2020 July Travel Give Into Your Wanderlust 广告 广告 WOMEN OF CHINA English Monthly Editors 编辑 Advertising 广告 《中 国 妇 女》英 文 月 刊 GU WENTONG 顾文同 LIU BINGBING 刘兵兵 WANG SHASHA 王莎莎 HE QIUJU 何秋菊 编辑顾问 Sponsored and administrated by Editorial Consultant Program 项目 All-China Women's Federation ROBERT MILLER(Canada) ZHANG GUANFANG 张冠芳 罗 伯 特·米 勒( 加 拿 大) 中华全国妇女联合会主管/主办 Published by Layout 设计 ACWF Internet Information and Deputy Director of Reporting Department FANG HAIBING 方海兵 Communication Center (Women's Foreign 信息采集部(记者部)副主任 Language Publications of China) LI WENJIE 李文杰 Legal Adviser 法律顾问 全国妇联网络信息传播中心 Reporters 记者 HUANG XIANYONG 黄显勇 (中 国 妇 女 外 文 期 刊 社)出 版 ZHANG JIAMIN 张佳敏 YE SHAN 叶珊 Publishing Date: July 15, 2020 International Distribution 国外发行 FAN WENJUN 樊文军 本期出版时间:2020年7月15日 China International Book Trading Corporation -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

不早不晚not Early Not Late

Chen Qiulin Ma Qiusha 陈秋林 马秋莎 Chen Yin-Ju Tse Su-Mei 陈滢如 谢素梅 Hao Jingban Yao Qingmei 郝敬班 姚清妹 Hu Xiaoyuan Yin Xiuzhen 胡晓媛 尹秀珍 Lai Chiu-Han 黎肖娴 Not不早不晚 Early Not Late 2016.08.04 - 2016.09.15 Press Release Pace Beijing is pleased to present Not Early Not Late at of both works. Whether walking or waiting, simple actions 佩斯北京荣幸地宣布暑期档展览“不早不晚”将于 2016 年 8 月 艺术家本人身着军官大衣,义愤填膺地批判着一台代表着资本 4pm on August 4, 2016. This is an exhibition of work by are cycled to create infinite repetition. The artists’ true 4 日下午 4 时向公众开幕。这是继 2014 年影像群展“这个夏天 主义的自动贩售机。这种恰到好处的幽默和荒诞感不仅并未冲 nine artists and focusing on video art once again after We intentions are hided beneath the removal of narrative on 我们爱影像”之后,佩斯北京对于录像艺术的再度呈现。 淡作品的批判性,相反的,它确保了思考这一行为所应保持的 Love Video this Summer in 2014. the surface. The significance of the act itself is opened up 适当距离感。姚清妹的“角色扮演”借用的是社会共享的文化 for the viewer to see, while individual viewers according to The exhibition features nine video works and screens, their own background and experience fill in the “story”. 此次参展的九部作品以屏幕为界,将展览分割出内部与外部的 语境,而黎肖娴的作品则直接挪用了语境中具有典型性的大众 creating into inner and outer space-time, have partitioned 两个时空。单个录像作品自身已构建出完整而独立的内部世界, 影视作品。在她的作品《戏门》中,艺术家单独将“门”这个 the whole site. Each single video itself has already Yao Qingmei directs and stars in works that bring clarity 但与此同时,它在屏幕这一输出设备上的每一次播放又将与当 在影视作品中通常起到场景、情节转换功能的典型道具提取出 established an integrated and independent internal world and completeness to this fragmented choreography. 下的时空、观看者、及其它作品间形成互文关系。而同样带有 来,影像片段原本的叙事功能被人为破坏,彻底成为了单纯的 while output devices, the screens, will form a intertextual By playing typical roles in the social power system, Yao relation with current spaces and spectators when every Qingmei brings her unique brand of humor to bear on a 时间属性的展览标题“不早不晚”则可被视为对所有即将产生 视觉性材料。同样是对经典电影片段的直接挪用,郝敬班在作 time it is playing. -

Best for Kids in Beijing"

"Best for Kids in Beijing" Créé par: Cityseeker 25 Emplacements marqués Forbidden City Concert Hall "Music for All" Forbidden City Concert Hall, located at the Zhongshan Park, is a veritable haven for lovers of eclectic music. Home to a wealth of classical concerts, music dos, live performances, orchestras, vocal, instrumental, solos and group performances, it is also called the Zhongshan Park Music Hall. It can easily seat a crowd of 1,400 and charms a huge number of patrons by Gene Zhang into admiring its blend of tradition and modernity. Brilliant acoustics and an even more brilliant line-up of live performances makes this a must visit while in the city. The concert hall organizes an annual two-month-long children arts festival called Open the Door to Art. +86 10 6559 8285 Donghuamen Road, Zhongshan Park, Xicheng, Pékin Hotel Kapok "Bon emplacement" Cet hôtel est situé à quelques minutes de la gare de Pékin et d'autres attractions populaires sur la rue Donghuamen. Cet hôtel quatre étoiles a été conçu par un architecte Chinois de renom, Pei Zhu. Que vous soyez là pour le plaisir ou pour les affaires, cet hôtel vous offre un environnement confortable pour encourager votre visite dans la ville. Pour la cuisine by Booking.com occidental dinez au restaurant Shuxiangmendi situé à l'hôtel. C'est un bel endroit avec beaucoup de facilités, un service amical et d'autres qualités qui vous laisseront un souvenir mémorable. Il y a aussi pas mal d'attractions dans le coin. +86 10 6525 9988 www.kapokhotelbeijing.com/ 16 Donghuamen Street, Pékin National Center for the Performing Arts "l'œuf est ouvert" Le Centre National de performances de la Chine, après six ans de construction et 400 millions en dépenses, a ouvert en Juin 2007. -

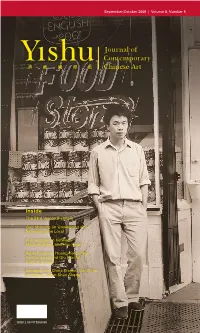

On Huang Yong Ping

September/October 2009 | Volume 8, Number 5 Inside The 53rd Venice Biennale Gao Shiming on Unweaving and Rebuilding the Local A Conversation between Michael Zheng and Hou Hanru Artist Features: Huang Yong Ping, Hu Xiaoyuan and Qiu Xiaofei, Chen Hui-chiao Reviews: The China Project, Qiu Zhijie, Ai Weiwei, Shan Shan Sheng US$12.00 NT$350.00 Ryan Holmberg The Snake and the Duck: On Huang Yong Ping “ lay sculpture is a term now used to describe an idea Isamu Huang Yong Ping, Tower Snake, 2009, aluminum, Noguchi began experimenting with in the late 930s: to use the bamboo, steel, 660 x 1189 x 1128 cm. Courtesy of the artist modernist vocabulary of sculptural form within the context of and Barbara Gladstone Gallery, P New York. leisure, recreation, and purposeless play. Most of what he designed was for children’s playgrounds and included angular swing sets in primary colors, cubistic climbing blocks, and biomorphic landscaping. At the same time, a fair number of these projects, none of which were realized in full before the 970s, have an atavistic subtext, from references to monuments of the ancient world to almost protozoan biological structures. As if to suggest that to play like a child is to reincarnate the most archaic forms of human civilization and the most primordial forms of life on earth. The same conceit resonates strongly in Tower Snake (2009), the newest work by Huang Yong Ping. First exhibited at Gladstone Gallery in New York in the summer of 2009, Tower Snake can be seen as a kind of “play sculpture” that links interactive amusement to ultimately atavistic fantasies. -

Copyright by Mariana Estrada 2009

Copyright by Mariana Estrada 2009 The Thesis Committee for Mariana Estrada Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Jia Zhangke’s Shijie and China’s Changing Global Space APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Chien-hsin Tsai Robert M. Oppenheim Jia Zhangke’s Shijie and China’s Changing Global Space by Mariana Estrada, B.A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2009 Abstract Jia Zhangke’s Shijie and China’s Changing Global Space Mariana Estrada, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2009 Supervisor: Chien-hsin Tsai This paper explores tourism and space-making in modern China through the lens of Sixth Generation Chinese filmmaker Jia Zhangke. His film Shijie (The World) features people whose lives play out in and around a Chinese theme park of the same name. Through its portrayal of theme parks and the social stratum who visit and inhabit them, Shijie depicts both the filmmaker‟s opinion of China‟s modernization project, as well as his evolving status within the Chinese international/national film system. As China‟s interest in its global image is being transformed through its media products, its concept of global and local space is also changing. The Olympic Village created for the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics can be seen as an attempt at physically and symbolically engineering China‟s new global space. This paper will consider Jia Zhangke, The World, and the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games as several points along a continuum that leads toward a new envisioning of global space in China. -

Dossier De Presse

MATT DAMON LE 11 JANVIER 2017 LEGENDARY PICTURES et UNIVERSAL PICTURES présentent une production LEGENDARY PICTURES / ATLAS ENTERTAINMENT (THE GREAT WALL) un film de ZHANG YIMOU avec MATT DAMON JING TIAN PEDRO PASCAL WILLEM DAFOE et ANDY LAU Produit par ERIC HADAYAT, ER YOUNG et ALEX HEDLUND Une histoire de MAX BROOKS, EDWARD ZWICK et MARSHALL HERSKOVITZ Scénario de CARLO BERNARD, DOUG MIRO et TONY GILROY SORTIE LE 11 JANVIER 2017 Durée : 1h44 Matériel disponible sur www.upimedia.com DISTRIBUTION PRESSE Universal Pictures International SYLVIE FORESTIER 21, rue François 1er YOUMALY BA 75008 Paris assistées de COLOMBE SIROT Tél. : 01 40 69 66 56 [email protected] www.lagrandemuraille-lefilm.com SYNOPSIS Entre le courage et l’effroi, l’humanité et la monstruosité, il existe une frontière qui ne doit en aucun cas céder. William Garin (Matt Damon), un mercenaire emprisonné dans les geôles de la Grande Muraille de Chine, découvre la fonction secrète de la plus colossale des merveilles du monde. L’édifice tremble sous les attaques incessantes de créatures monstrueuses, dont l’acharnement n’a d’égal que leur soif d’anéantir l’espèce humaine dans sa totalité. Il rejoint alors ses geôliers, une faction d’élite de l’armée chinoise, dans un ultime affrontement pour la survie de l’humanité. C’est en combattant cette force incommensurable qu’il trouvera sa véritable vocation : l’héroïsme. - 2 - - 3 - NOTES DE PRODUCTION AU CŒUR DE LA MURAILLE : LA TRAME DU FILM L’histoire de LA GRANDE MURAILLE se déroule au nord de la Chine, à une époque très lointaine. -

Memorias Del Club De Cine: Más Allá De La Pantalla 2008-2015

Memorias del Club de Cine: Más allá de la pantalla 2008-2015 MAURICIO LAURENS UNIVERSIDAD EXTERNADO DE COLOMBIA Decanatura Cultural © 2016, UNIVERSIDAD EXTERNADO DE COLOMBIA Calle 12 n.º 1-17 Este, Bogotá Tel. (57 1) 342 0288 [email protected] www.uexternado.edu.co ISSN 2145 9827 Primera edición: octubre del 2016 Diseño de cubierta: Departamento de Publicaciones Composición: Precolombi EU-David Reyes Impresión y encuadernación: Digiprint Editores S.A.S. Tiraje de 1 a 1.200 ejemplares Impreso en Colombia Printed in Colombia Cuadernos culturales n.º 9 Universidad Externado de Colombia Juan Carlos Henao Rector Miguel Méndez Camacho Decano Cultural 7 CONTENIDO Prólogo (1) Más allá de la pantalla –y de su pedagogía– Hugo Chaparro Valderrama 15 Prólogo (2) El cine, una experiencia estética como mediación pedagógica Luz Marina Pava 19 Metodología y presentación 25 Convenciones 29 CUADERNOS CULTURALES N.º 9 8 CAPÍTULOS SEMESTRALES: 2008 - 2015 I. RELATOS NUEVOS Rupturas narrativas 31 I.1 El espejo - I.2 El diablo probablemente - I.3 Padre Padrone - I.4 Vacas - I.5 Escenas frente al mar - I.6 El almuerzo desnudo - I.7 La ciudad de los niños perdidos - I.8 Autopista perdida - I.9 El gran Lebowski - I.10 Japón - I.11 Elephant - I.12 Café y cigarrillos - I.13 2046: los secretos del amor - I.14 Whisky - I.15 Luces al atardecer. II. DEL LIBRO A LA PANTALLA Adaptaciones escénicas y literarias 55 II.1 La bestia humana - II.2 Hamlet - II.3 Trono de sangre (Macbeth) - II.4 El Decamerón - II.5 Muerte en Venecia - II.6 Atrapado sin salida - II.7 El resplandor - II.8 Cóndores no entierran todos los días - II.9 Habitación con vista - II.10 La casa de los espíritus - II.11 Retrato de una dama - II.12 Letras prohibidas - II.13 Las horas. -

Tour Code : Cdg (Gv2)

TOUR CODE : CDG (GV2) Special Meal ~ Muslim Dumplings, Xingjiang Dance Dinner Show, Tianjin Mutton in Hot Pot Day 1 Kuala Lumpur / Beijing (L/D) Tian An Men Square ~ largest city square in the world, bordered by the Great Hall of the People and Chairman Mao’s Mausoleum Forbidden City ~ the complex of imperial palace, which was home to the Emperors for over 500 years. Grand halls and courts gradually give way to more intimate domestic quarters, giving an insight into the pampered isolation of the emperors Niujie Mosque ~ is the oldest Mosque with over one thousand year’s history Muslim Super Market ~ is the biggest Muslim Super market in Beijing and has varies Islamic food Acrobatics Show ~ World Famous Chinese Acrobatics, give you newer, harder and more magic experiences, Masculine Springboard, Rings and Balance Skills; Graceful Silk hangs, Jujustu; Smart diabolo, Water Meteor; Incredible Chinese Traditional Face Changing and etc Day 2 Beijing (B/L/D) Juyongguan Great Wall of China ~ First built in the Warring States period (475-221BC) as a series of earthworks erected by individual kingdoms as a defense against each other as well as from invasions from the north, the wall we see in the present day was left from the Ming Dynasty Wang Fu Jing Shopping Street &Night Food Market ~ where you will see a collection of Halal snacks Outside Olympic Stadiums ~ the prestigious Bird’s Nest & Water Cube Day 3 Beijing (B/L/D) Summer Palace ~ being the largest imperial garden in China, the Summer Palace was first built in the Qing emperor Qianlong’s time in 1751 and burned down in1860 by the French and British army and restored by the Dowager empress Cixi for her own enjoyment. -

Four Asian Filmmakers Visualize the Transnational Imaginary Stephen Edward Spence University of New Mexico

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 4-17-2017 "Revealing Reality": Four Asian Filmmakers Visualize the Transnational Imaginary Stephen Edward Spence University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Part of the American Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Spence, Stephen Edward. ""Revealing Reality": Four Asian Filmmakers Visualize the Transnational Imaginary." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/54 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Stephen Edward Spence Candidate American Studies Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Rebecca Schreiber, Chairperson Alyosha Goldstein Susan Dever Luisela Alvaray ii "REVEALING REALITY": FOUR ASIAN FILMMAKERS VISUALIZE THE TRANSNATIONAL IMAGINARY by STEPHEN EDWARD SPENCE B.A., English, University of New Mexico, 1995 M.A., Comparative Literature & Cultural Studies, University of New Mexico, 2002 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2017 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project has been long in the making, and therefore requires substantial acknowledgments of gratitude and recognition. First, I would like to thank my fellow students in the American Studies Graduate cohort of 2003 (and several years following) who always offered support and friendship in the earliest years of this project. -

Negotiating Transnational Collaborations with the Chinese Film Industry

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 2017+ University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2019 Negotiating Transnational Collaborations with the Chinese Film Industry Kai Ruo Soh University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1 University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Soh, Kai Ruo, Negotiating Transnational Collaborations with the Chinese Film Industry, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of the Arts, English and Media, University of Wollongong, 2019.