Copyright by Mariana Estrada 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travel Give Into Your Wanderlust 广告

广告 July 2020 Plus: A Beijing Family Scavenger Hunt Insider Knowledge: Put Your Trust in Beijing’s Best Local Tour Guides and Really Explore The City You Call Home Travel Give Into Your Wanderlust 广告 July 2020 Plus: A Beijing Family Scavenger Hunt Insider Knowledge: Put Your Trust in Beijing’s Best Local Tour Guides and Really Explore The City You Call Home Travel Give Into Your Wanderlust WOMEN OF CHINA WOMEN July 2020 PRICE: RMB¥10.00 US$10 Plus: A Beijing Family Scavenger O Hunt 《中国妇女》 Insider Knowledge: Put Your Trust in Beijing’s Beijing’s essential international family resource resource family international essential Beijing’s Best Local Tour Guides and Really Explore The City You Call Home 国际标准刊号:ISSN 1000-9388 国内统一刊号:CN 11-1704/C July 2020 July Travel Give Into Your Wanderlust 广告 广告 WOMEN OF CHINA English Monthly Editors 编辑 Advertising 广告 《中 国 妇 女》英 文 月 刊 GU WENTONG 顾文同 LIU BINGBING 刘兵兵 WANG SHASHA 王莎莎 HE QIUJU 何秋菊 编辑顾问 Sponsored and administrated by Editorial Consultant Program 项目 All-China Women's Federation ROBERT MILLER(Canada) ZHANG GUANFANG 张冠芳 罗 伯 特·米 勒( 加 拿 大) 中华全国妇女联合会主管/主办 Published by Layout 设计 ACWF Internet Information and Deputy Director of Reporting Department FANG HAIBING 方海兵 Communication Center (Women's Foreign 信息采集部(记者部)副主任 Language Publications of China) LI WENJIE 李文杰 Legal Adviser 法律顾问 全国妇联网络信息传播中心 Reporters 记者 HUANG XIANYONG 黄显勇 (中 国 妇 女 外 文 期 刊 社)出 版 ZHANG JIAMIN 张佳敏 YE SHAN 叶珊 Publishing Date: July 15, 2020 International Distribution 国外发行 FAN WENJUN 樊文军 本期出版时间:2020年7月15日 China International Book Trading Corporation -

Best for Kids in Beijing"

"Best for Kids in Beijing" Créé par: Cityseeker 25 Emplacements marqués Forbidden City Concert Hall "Music for All" Forbidden City Concert Hall, located at the Zhongshan Park, is a veritable haven for lovers of eclectic music. Home to a wealth of classical concerts, music dos, live performances, orchestras, vocal, instrumental, solos and group performances, it is also called the Zhongshan Park Music Hall. It can easily seat a crowd of 1,400 and charms a huge number of patrons by Gene Zhang into admiring its blend of tradition and modernity. Brilliant acoustics and an even more brilliant line-up of live performances makes this a must visit while in the city. The concert hall organizes an annual two-month-long children arts festival called Open the Door to Art. +86 10 6559 8285 Donghuamen Road, Zhongshan Park, Xicheng, Pékin Hotel Kapok "Bon emplacement" Cet hôtel est situé à quelques minutes de la gare de Pékin et d'autres attractions populaires sur la rue Donghuamen. Cet hôtel quatre étoiles a été conçu par un architecte Chinois de renom, Pei Zhu. Que vous soyez là pour le plaisir ou pour les affaires, cet hôtel vous offre un environnement confortable pour encourager votre visite dans la ville. Pour la cuisine by Booking.com occidental dinez au restaurant Shuxiangmendi situé à l'hôtel. C'est un bel endroit avec beaucoup de facilités, un service amical et d'autres qualités qui vous laisseront un souvenir mémorable. Il y a aussi pas mal d'attractions dans le coin. +86 10 6525 9988 www.kapokhotelbeijing.com/ 16 Donghuamen Street, Pékin National Center for the Performing Arts "l'œuf est ouvert" Le Centre National de performances de la Chine, après six ans de construction et 400 millions en dépenses, a ouvert en Juin 2007. -

On Huang Yong Ping

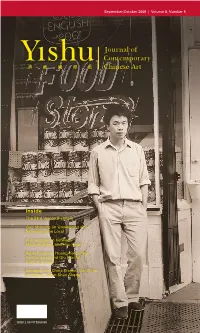

September/October 2009 | Volume 8, Number 5 Inside The 53rd Venice Biennale Gao Shiming on Unweaving and Rebuilding the Local A Conversation between Michael Zheng and Hou Hanru Artist Features: Huang Yong Ping, Hu Xiaoyuan and Qiu Xiaofei, Chen Hui-chiao Reviews: The China Project, Qiu Zhijie, Ai Weiwei, Shan Shan Sheng US$12.00 NT$350.00 Ryan Holmberg The Snake and the Duck: On Huang Yong Ping “ lay sculpture is a term now used to describe an idea Isamu Huang Yong Ping, Tower Snake, 2009, aluminum, Noguchi began experimenting with in the late 930s: to use the bamboo, steel, 660 x 1189 x 1128 cm. Courtesy of the artist modernist vocabulary of sculptural form within the context of and Barbara Gladstone Gallery, P New York. leisure, recreation, and purposeless play. Most of what he designed was for children’s playgrounds and included angular swing sets in primary colors, cubistic climbing blocks, and biomorphic landscaping. At the same time, a fair number of these projects, none of which were realized in full before the 970s, have an atavistic subtext, from references to monuments of the ancient world to almost protozoan biological structures. As if to suggest that to play like a child is to reincarnate the most archaic forms of human civilization and the most primordial forms of life on earth. The same conceit resonates strongly in Tower Snake (2009), the newest work by Huang Yong Ping. First exhibited at Gladstone Gallery in New York in the summer of 2009, Tower Snake can be seen as a kind of “play sculpture” that links interactive amusement to ultimately atavistic fantasies. -

On Huang Yong Ping 69 Ryan Holmberg

: septemb / octob 9 September/October 2009 | Volume 8, Number 5 Inside The 53rd Venice Biennale Gao Shiming on Unweaving and Rebuilding the Local A Conversation between Michael Zheng and Hou Hanru Artist Features: Huang Yong Ping, Hu Xiaoyuan and Qiu Xiaofei, Chen Hui-chiao Reviews: The China Project, Qiu Zhijie, Ai Weiwei, Shan Shan Sheng US$12.00 NT$350.00 6 VOLUME 8, NUMBER 5, SEPTember/OCTober 2009 CONTENTS 2 Editor’s Note 47 4 Contributors 6 Making Worlds: The 53rd Venice Biennale Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker 29 A Be-Coming Future: The Unweaving and Rebuilding of the Local Gao Shiming 38 The Snake and the Duck: On Huang Yong Ping 69 Ryan Holmberg 47 Objectivity, Absurdity, and Social Critique: A Conversation with Hou Hanru Michael Zheng 62 A Conversation with Hu Xiaoyuan and Qiu Xiaofei Danielle Shang 69 Dreaming through Art: On Chen Hui-chiao 75 Chia Chi Jason Wang 75 The China Project Inga Walton 89 Qiu Zhijie at Chambers Fine Art Jonathan Goodman 95 The Visual Roots of a Public Intellectual’s Social Conscience: Ai Weiwei’s New York Photographs Maya Kóvskaya 89 0 Shan Shan Sheng’s Open Wall Inhee Iris Moon 06 Chinese Name Index 95 Cover: Ai Weiwei, Williamsburg, Brooklyn (detail), 1983, silver gelation print, © Ai Weiwei. Courtesy of Three Shadows Photography Art Center, Beijing. Editor’s Note YISHU: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art president Katy Hsiu-chih Chien The first four texts inYishu 34 tackle different r Ken Lum topics and concerns, yet it is striking how certain r Keith Wallace issues—the postcolonial, cultural hybridity, the n r Zheng Shengtian Chinese diaspora, and the ongoing negotiation i Julie Grundvig between the local and global—resonate Kate Steinmann among them. -

Tour Code : Cdg (Gv2)

TOUR CODE : CDG (GV2) Special Meal ~ Muslim Dumplings, Xingjiang Dance Dinner Show, Tianjin Mutton in Hot Pot Day 1 Kuala Lumpur / Beijing (L/D) Tian An Men Square ~ largest city square in the world, bordered by the Great Hall of the People and Chairman Mao’s Mausoleum Forbidden City ~ the complex of imperial palace, which was home to the Emperors for over 500 years. Grand halls and courts gradually give way to more intimate domestic quarters, giving an insight into the pampered isolation of the emperors Niujie Mosque ~ is the oldest Mosque with over one thousand year’s history Muslim Super Market ~ is the biggest Muslim Super market in Beijing and has varies Islamic food Acrobatics Show ~ World Famous Chinese Acrobatics, give you newer, harder and more magic experiences, Masculine Springboard, Rings and Balance Skills; Graceful Silk hangs, Jujustu; Smart diabolo, Water Meteor; Incredible Chinese Traditional Face Changing and etc Day 2 Beijing (B/L/D) Juyongguan Great Wall of China ~ First built in the Warring States period (475-221BC) as a series of earthworks erected by individual kingdoms as a defense against each other as well as from invasions from the north, the wall we see in the present day was left from the Ming Dynasty Wang Fu Jing Shopping Street &Night Food Market ~ where you will see a collection of Halal snacks Outside Olympic Stadiums ~ the prestigious Bird’s Nest & Water Cube Day 3 Beijing (B/L/D) Summer Palace ~ being the largest imperial garden in China, the Summer Palace was first built in the Qing emperor Qianlong’s time in 1751 and burned down in1860 by the French and British army and restored by the Dowager empress Cixi for her own enjoyment. -

Four Asian Filmmakers Visualize the Transnational Imaginary Stephen Edward Spence University of New Mexico

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository American Studies ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 4-17-2017 "Revealing Reality": Four Asian Filmmakers Visualize the Transnational Imaginary Stephen Edward Spence University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds Part of the American Studies Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Recommended Citation Spence, Stephen Edward. ""Revealing Reality": Four Asian Filmmakers Visualize the Transnational Imaginary." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/amst_etds/54 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Studies ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Stephen Edward Spence Candidate American Studies Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Rebecca Schreiber, Chairperson Alyosha Goldstein Susan Dever Luisela Alvaray ii "REVEALING REALITY": FOUR ASIAN FILMMAKERS VISUALIZE THE TRANSNATIONAL IMAGINARY by STEPHEN EDWARD SPENCE B.A., English, University of New Mexico, 1995 M.A., Comparative Literature & Cultural Studies, University of New Mexico, 2002 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy American Studies The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2017 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project has been long in the making, and therefore requires substantial acknowledgments of gratitude and recognition. First, I would like to thank my fellow students in the American Studies Graduate cohort of 2003 (and several years following) who always offered support and friendship in the earliest years of this project. -

Absences and Excesses in Cinematic Representations of Beijing

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Absences and Excesses in Cinematic Representations of Beijing Yinghong Li “Reality is a mess in China”–Jia Zhangke Social reality of postsocialist China can only be described in polysemic terms bearing contradictory or at least conflicting connotations. The phantasmagoric na- ture and the immeasurable dimension of this historical condition make it an infinitely challenging object of study for anyone interested in any aspect of contem- porary China.1) The past three decades or so brought drastic changes to China that have fundamentally altered formations of the social structure and the individual’s position and function in this structure, forcing Chinese people to re-orient them- selves in the way they experience the world and interact with each other. The tri- umph of global capitalism at “the end of history” brings China an enormous explo- sion of energy with which the ordinary Chinese have marched forward toward accumulating greater amount of wealth and experiencing greater satisfactions of pleasure. It has also impacted essential moral, ethical standards and thinking hon- ored by conventional wisdom and habit, ushered in different sets of values, beliefs and practices, many of which are potentially more problematic than beneficial. In this paper I would like to examine postsocialist China from two important as- pects, namely the family in disintegration and the workings of the body politics that exploit the weak and encourage the return of many repressed desires of the previous regime. By using cinematic lens as a tool and Beijing as focus, this paper intends to ask pertinent questions regarding how the human subject struggles to re-define the meaning of moral agency and re-negotiate various power relations in order to make sense of a tumultuous and mundane interiority, and an equally devastating exterior formed in sharp contrast between polished, smooth industrial steel and concrete and pathetic, cast-away grey bricks. -

View / Download 3.7 Mb

The People’s Republic of Capitalism: The Making of the New Middle Class in Post-Socialist China, 1978-Present by Ka Man Calvin Hui Program in Literature Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Rey Chow, Supervisor ___________________________ Michael Hardt, Supervisor ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Robyn Wiegman ___________________________ Leo Ching Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program in Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2013 i v ABSTRACT The People’s Republic of Capitalism: The Making of the New Middle Class in Post-Socialist China, 1978-Present by Ka Man Calvin Hui Program in Literature Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Rey Chow, Supervisor ___________________________ Michael Hardt, Supervisor ___________________________ Fredric Jameson ___________________________ Robyn Wiegman ___________________________ Leo Ching An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Program in Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2013 Copyright by Ka Man Calvin Hui 2013 Abstract My dissertation, “The People’s Republic of Capitalism: The Making of the New Middle Class in Post-Socialist China, 1978-Present,” draws on a range of visual cultural forms – cinema, documentary, and fashion – to track the cultural dimension of the emergence -

What About You?

THE TOXIC TERROR OF TOYS P8 WHAT ABOUT YOU? ECOLOGICAL ECONOMY CN 53-1197/F ISSN1673-0178 WIN VALENTINE'SDINNERSP12 JANUARY 02 Beijing Folk: A wedding emcee with heart CITY SCENE Going Underground: Wangfujing, Line 1 Scene & Heard: Movers and shakers … plus your chance to win great prizes ECOLOGICAL ECONOMY 08 生态经济(英文版) ECOLOGY 主管单位: 云南出版集团公司 Feature: What perils lurk among the playthings of 主办单位: 云南教育出版社 children? And it’s not just toys we have to watch 出版: 生态经济杂志社 out for. 社长: 李安泰 主编: 高晓铃 13 地址: 昆明市环城西路609号云南新闻出版大楼4楼 Beijing, how do we love thee? There are seven types 邮政编码: 650034 COVER FEATURE of love, as it happens, and we’re overflowing with 国内统一刊号: CN53-1197/F ideas. 国际标准刊号: ISSN1673 – 0178 Editorial Planning Manager Jonathan White 19 Deputy Editorial Planning Manager Iain Shaw What’s New: Bianyifang, Temple Restaurant Beijing, Style and Living Editorial Planner Tiffany Wang Dining Haney Restaurant, Pho La La, Thai Express, WasPark Music Editorial Planner Michelle Dai Feature: Coffee gets serious Arts & Culture Editorial Planner Marilyn Mai Taste Test: Chocolate bars Explore Editorial Planner Lauren McCarthy A Taste of Home: South Korea Dining Editorial Assistant Susan Sheng 31 Contributing Editor Tom O’Malley What’s New: The Drive-Thru, Doron, Wu and Twilo Copy Editor Lilly Chow BARS & CLUBS Party Like A: Newspaper classifieds Visual Planning Joey Guo Clubhouse: M.Ross Contributors Aika Ashimova, Mary Dennis, Mastermind: Mike Bromley, 12SQM George Ding, Kyle Mullin, John Pullman, Edward Ragg, Lou Waterstone 37 Advertising Agency -

Must Visit Attractions in Beijing"

"Must Visit Attractions in Beijing" Gecreëerd door : Cityseeker 9 Locaties in uw favorieten Tiananmen Gate "Symbool Voor Oud en Nieuw China" Bezoekers die op het platform staan van de Gate of Heavenly Peace hebben een panoramisch uitzicht over Tiananmen Square. Gebouwd in 1417 bestaat dit 34 meter (110 foot) hoge gebouw uit een terras en een toren. Vroeger werd deze plek gebruikt voor grote ceremonies in de Ming en Qing dynastieën. Het is vier keer gerenoveerd in de laatste 50 jaar en by Bernt Rostad is heropend voor publiek op 1 juli 988. Tiananmen, de poort aan de voorkant van de Verboden Stad, wordt het centrum van Beijing beschouwd. english.visitbeijing.com.cn/ 4 West Chan'an Avenue, Peking Meridian Gate "South Gate Entrance to the Forbidden City" Helping to ease the flow of visitors to the Forbidden City, the Meridian Gate acts as its primary entrance. Visitors travel from the south to north as the explore this vast complex. This particular gate features five distinct arches and is the largest structure in the entire complex towering 37 meters (125 feet) into the air. Historically, the gate offered five different by niceguy_eddie doors, one for the emperor, three for the top scholars of the era and one for ministers and officials. The gate and entire complex was believed to be built along the Meridian, because the emperor's believed themselves to be the sons of the universe and therefore should live at the center of it. +86 10 8500 7427 (Tourist Information) 4 Jing Shan Qian Jie, Peking Verboden Stad "Het Grootste Keizerlijke Paleis van China" De Verboden Stad, ook bekend als het Voormalig Paleis was de keizerlijke residentie van de Ming (1368-1644) en Qing (1644-1911) Dynastie. -

2012 CHINESE FILM LIST a Guide for American Viewers

Carolyn Bloomer’s 2012 CHINESE FILM LIST A Guide for American Viewers © Carolyn M Bloomer, Ph.D. Ringling College of Art and Design Sarasota, Florida Distributed by US-China Peoples Friendship Association – Southern Region (USCPFA) ©2012 Carolyn M Bloomer, Ph.D. Carolyn Bloomer’s 2012 Chinese Film List: A Guide for American Viewers is fully protected intellectual property covered by US copyright and international treaties regarding protection of intellectual property (IP). Permission is granted for reproduction or quotation of whole or parts, providing the usage meets all the following conditions: 1) authorship and copyright are clearly indicated; 2) the usage is for non-commercial purposes (e.g. private, educational, research, or review use); 3) USCPFA – Southern Region is credited as authorized distributor; 4) any editing or ellipsis must be clearly indicated in accordance with standard academic practice. Any other usage or appropriation in the absence of written permission from the author is not allowed and may be prosecuted pursuant to the applicable law. All questions or communications concerning Carolyn Bloomer’s 2012 Chinese Film List: A Guide for American Viewers should be addressed to: Carolyn M Bloomer, Ph.D. Ringling College of Art and Design 2700 N Tamiami Train Sarasota, Florida 34234 or [email protected] www.carolynbloomer.com Acknowledgements Thanks go first of all to Peggy Roney, President of the US-China Peoples Friendship Association – Southern Region, for her unwavering support and enthusiasm for this project. Peggy was the first person to ask if I would share information and resources about films I had been showing in Sarasota, as part of a project she is creating for the Southern Region chapters and for USCPFA-National for chapters nationwide, to develop chapter membership and retention. -

RHA 12 Integral.Pdf

Crise N.º 1 2 2015 issn 1646-1762 issn faculdade de ciências sociais e humanas – nova Crise N.º 12 2015 Instituto de História da Arte Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas Universidade Nova de Lisboa Edição Instituto de História da Arte abreviaturas ACSL Arquivo do Cabido da Sé de Lisboa ADP Arquivo Distrital do Porto AHTC Arquivo Histórico do Tribunal de Contas AISS Arquivo da Irmandade do Santíssimo Sacramento AMCB Arxiu Municipal Contemporani de Barcelona AML Arquivo Municipal de Lisboa ANBA Academia Nacional de Belas-Artes ANSL/AHIL Archivio de Nossa Senhora di Loreto AOS Arquivo Oliveira Salazar APL Arquivo do Patriarcado de Lisboa ASV Archivio Segreto Vaticano BNRJ Biblioteca Nacional do Rio de Janeiro BNUT Biblioteca Nazionale Universitaria di Torino CESEM Centro de Estudos de Sociologia e Estética Musical CML Câmara Municipal de Lisboa CNL Cartórios Notariais de Lisboa DGEMN Direcção Geral dos Edifícios e Monumentos Nacionais DGLAB/TT Direcção Geral do Livro, dos Arquivos e das Bibliotecas / Torre do Tombo DGPC Direcção Geral do Património Cultural FCSH/UNL Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa FCG Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian FCT Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia Fig. Figura FLUL Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa GEAEM-DIE Gabinete de Estudos Arqueológicos de Engenharia Militar da Direcção de Infra-Estruturas IHA Instituto de História da Arte IHC Instituto de História Contemporânea IHRU nstituto da Habitação e da Reabilitação Urbana IPPAR Instituto Português do Património Arquitectónico