B. Background of Molson Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America CANADA

North America CANADA Gallons Guzzled 17.49 Gal Per Person Per Year Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Alberta Calgary Big Rock Brewery McNally's Ale Dec-01 15.5 5.0% Gary B. www.bigrockbeer.com Cold Cock Winter Porter May-09 17.0 Gary B. Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site British Columbia Pacific Western Brewing Prince George Bulldog Canadian Lager May-09 16.0 Helen B. Company Vancouver Molson Breweries Molson Canadian Lager May-05 17.0 5.0% Helen B. Vancouver Island Brewing Vancouver Piper's Pale Ale May-09 16.0 Helen B. Company Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Manitoba Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site New Brunswick Saint John Moosehead Brewery Moosehead Lager Jul-01 17.0 5.1% Gary B. Moosehead Light Lager Sep-09 15.0 4.8% Maurice S. Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site New Foundland St. John's Labatt Brewing Company Budweiser Lager Sep-02 18.0 5.0% Gary B. Bud Light Lager Sep-02 16.0 4.0% Gary B. St. John's Molson Brewery L.T.D. Black Horse Lager Sep-02 18.5 5.0% Gary B. Molson Canadian Lager Sep-09 17.5 5.0% Maurice S. Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Northwest Territories Country/State/City Brewery Beer Date Rating Alc.% Thanks Web Site Nova Scotia Halifax Labatt Brewing Company Labatt's Blue Pilsner Set-02 16.0 4.3% Maurice S. -

Calgary City 1973 Jun M

234 Lukas—Lynch Lundgren J 7-4610 40AvSW 249-9574 Lust Leah 3109 38StSW 242-4768 LuU Wilf SlOSMaryvaleDrNE 272-(8C Lnndgren J 0 2630 13AvSE 272-3728 Lust Phltip ll-300BowValleyLd9S 262-2833 Lutz Wilfred H 3212ExshawRdNW 289-3C.< Lukjs Manfred C 3215CoiiradCr 289-5207 Lundgren R F 1314 42StSE 272-5177 Lust W J Sr 6324BowwoodDrNW 288-2060 Lutz William 1713 42StSE 272-3U Lulcas Tony 102-1222 ISAvSW 245-2634 Lundie J D 2025 42AvSW 243-4819 Lust William E 4723VanguardPINW .. .288-4370 Lutzko Ed 207 64AvNW 274-MM Uiicas Victor 132MarwoodC1rcleNE ....272-2390 Lundln Leroy 413 36Avt(W 276-2469 Lustig A 428 40StSW 242-2187 Luvlsotto John 7420 7StSW 253-lME Lntee A 1136 ISAvSW 244-3574 Limdman R A 2216 36StSW 249-2602 Lustig J 205-1830 llAvSW 244-4241 Lux Donald E 8512AshwDrthRdSE 2S5-6C1 Luke G P 919 20A»NW 289-2475 Lundman T 35HaiieyRd 255-6549 LusUg VIckl 101-1815 l6aStSW 245-5806 Lux H 208-2010UlsterRdlMW 282-6aP Luke Mrs Louise 502-1901 19StNE ...277-9592 Lundmarit Martin 400BVincentPlaceNW 288-8736 LutcJiman M 347 94AvSE 253-2489 Lux Windows 65llBownessRdNW 286-77r; Lukeman Jotm 726 OakhlllPlaceSW ....281-2124 Lundmark Nels 1917 21AvNW 289-1524 Lirteitach A 528CantarburyDrSW 281-4850 Luxford D E 91BakerCr 282-2r* Lukenblll A 103-1225 14AvSW 245-5416 Lundqulst A 0317-4020 37StSW 249-1175 Luterbach Norman Vincent Luxford Mrs E 0 810 24AvSE 265-lW Lukenbill Cecil STWilteOakCrSW 242-1548 Lundqidst Mrs A«a M lORundleLdg 266-1773 5003BrisebolsDrNW. .282-2287 LUXFORD DR E W PAUL Oral Surgy Lokenbill Durward L 124 l49AvSE ...271-0650 Lundqulst Carl C 23HarvardStNW 289-8069 Lutes R 4007 25AVSW 242-6223 628 12AVSW. -

2009-2012 Barrie Advance Ca

COLLECTIVE AGREEMENT between METROLAND MEDIA GROUP LTD. - and - COMMUNICATIONS, ENERGY AND PAPERWORKERS UNION OF CANADA SOUTHERN ONTARIO NEWSMEDIA GUILD LOCAL 87-M BARRIE ADVERTISING SALES DEPARTMENTS Ratified February 8, 2010 August 31, 2009 to August 31, 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS LOCAL HISTORY 5 PREAMBLE 10 ARTICLE 1 – RELATIONSHIP 10 1.01 Recognition 10 1.02 Union Membership 10 1.03 Deduction of Union Dues 10 ARTICLE 2 – MANAGEMENT RIGHTS 10 ARTICLE 3 – NEW EMPLOYEES 11 3.01 Probationary Period 11 ARTICLE 4 – PART-TIME & TEMPORARY EMPLOYEES 11 4.01 Part-time Employees 11 4.02 Excluded Clauses 11 4.03 Part-time Benefits 11 4.04 Working Full-time Hours 12 4.05 Part-time Wages 12 4.06 Temporary Employees 12 4.07 Excluded Clauses 12 4.08 Temporary Seniority 12 ARTICLE 5 – INFORMATION 12 ARTICLE 6 – NO STRIKE OR LOCK-0UT 13 ARTICLE 7 – NO DISCRIMINATION 13 ARTICLE 8 – STEWARDS 13 ARTICLE 9 – GRIEVANCE PROCEDURE 13 ARTICLE 10 – ARBITRATION 15 ARTICLE 11 – HEALTH & SAFETY 16 ARTICLE 12 – JOB POSTINGS 16 12.01 Posting and Selection 16 12.02 Trial Period 16 ARTICLE 13 – DISCIPLINE & DISCHARGE 17 2 13.01 Just Cause 17 13.02 Discharge Grievance 17 13.03 Employee Files 17 ARTICLE 14 – TERMINATION 17 14.01 Continuity of Service 17 14.02 Notice 17 ARTICLE 15 – SENIORITY & SECURITY 17 15.01 Seniority 17 15.02 Layoffs 18 15.03 Severance Pay 18 15.04 Benefit Continuance 18 15.05 Vacancies 18 ARTICLE 16 – HOURS OF WORK 18 16.01 Work Week 18 16.02 Overtime 18 ARTICLE 17 – CLASSIFICATIONS AND WAGES 19 17.01 Weekly Salaries 19 17.02 Weekly Pay 19 17.03 Experience -

The Mitre .V 4

■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ I .-BBBBBBBBBBBBB ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■■■ ■ ■ ■ ■ i V . V ana l ■■■■■ BB BBB b aW." a a ■ a .V a ■ a b ■ ■ ■ b ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ b b b b b b b b b bI bBB a ■B aB_B al BB_B § _BBBBaaaai ■ B B B B BB B B B B B B BBBB B B B B b b a b b b ana a a AE V b ■a _ a " S _B_B B_B .W B l " A t THE MITRE .V 4 .V¥ c & l i b r a r y : M OT T O 3 2 T A K E N AWAY Published by the Students of the University of Bishop’s College Lennoxville/ Quebec Volume 41, Number 3 February, 1934 W■ BBBBBBBB .V A ".V ,V"-.V -- - JV■JjV aVaVaVa,aVaVBVBVaVBVaVB,BlV jjV V V V lB B B B *B B B, B B. BJ« THE MITRE, February , 1934 UNIVERSITY OF BISHOP'S COLLEGE LENNOXVILLE, P. Q. Founded 1843 R oyal C harter 18 53 THE ONLY COLLEGE IN CANADA FOLLOWING THE OXFORD AND CAMBRIDGE PLAN OF THREE LONG ACADEMIC YEARS FOR THE B.A. DEGREE Complete courses in Arts and Divinity. Post-graduate couises in Education leading to High School Diploma. Residential College for men. Women students admitted to lectures and degrees. Valuable Scholarships and Exhibitions. The Col lege is beautifully situated at the junction of the St. Francis and Massawippi Rivers. Excellent buildings and equipment. All forms of recreation including tennis, badminton, and skiing. Private golf course. Lennoxville is within easy motoring dis tance of Quebec and Montreal, and has good railway connections. -

The Canadian Brewing Industry's Response to Prohibition, 1874-1920

The Canadian Brewing Industry’s Response to Prohibition, 1874-1920 Matthew J Bellamy The prohibitionist are putting us out of terms of the nation-forming British North business, so that we have lost heavily.1 America Act of 1867, the provinces had the constitutional power to prohibit the A.E. Cross, Calgary Brewing and retail sale of intoxicating drink. This vast Malting Co., 1916 power was first exercised by Canada's smallest province, Prince Edward Island; At the dawn of the twentieth century, its prohibition period lasted the longest - prohibition became part of a broader from 1901 to 1948. Nova Scotia was impulse in North American and Nordic the next Canadian province to jump countries to regulate the production and aboard the wagon (1916 to 1930), then consumption of alcoholic beverages. In came Ontario (1916 to 1927), Alberta some nations the ‘noble experiment’ last- (1916 to 1924), Manitoba (1916 to 1923), ed longer than in others. For instance, in Saskatchewan, (1917-1925), New the Russian Empire and Soviet Union Brunswick (1917 to 1927), British prohibition existed from 1914 to 1925; in Columbia (1917 to 1921), and the Yukon Iceland it lasted from 1915 to 1922; in Territory (1918-1921). Newfoundland, Norway it remained a sobering fact of life which was not part of Canada at that for eleven years (1916-1927); in Finland time, imposed prohibition in 1917 and prohibition was enforced from 1919 to repealed it in 1924. Quebec's experiment 1932 - thirteen long years, the same with banning the sale of all alcoholic amount of time that it existed in the drinks, in 1919, lasted only a few months. -

Visions of Canada: Photographs and History in a Museum, 1921-1967

Visions of Canada: Photographs and History in a Museum, 1921-1967 Heather McNabb A Thesis In the Department of History Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada May 2015 © Heather McNabb 2015 ii iii ABSTRACT Visions of Canada: Photographs and History in a Museum, 1921-1967 Heather McNabb, PhD. Concordia University, 2015 This dissertation is an exploration of the changing role of photographs used in the dissemination of history by a twentieth-century Canadian history museum. Based on archival research, the study focuses on some of the changes that occurred in museum practice over four and a half decades at Montreal’s McCord Museum. The McCord was in many ways typical of other small history museums of its time, and this work illuminates some of the transformations undergone by other similar organizations in an era of professionalization of many fields, including those of academic and public history. Much has been written in recent scholarly literature on the subject of photographs and the past. Many of these works, however, have tended to examine the original context in which the photographic material was taken, as well as its initial use(s). Instead, this study takes as its starting point the way in which historic photographs were employed over time, after they had arrived within the space of the museum. Archival research for this dissertation suggests that photographs, initially considered useful primarily for reference purposes at the McCord Museum in the early twentieth century, gradually gained acceptance as historical objects to be exhibited in their own right, depicting specific moments from the past to visitors. -

From Waterloo Snack Start-Up to Multinational in 4

LAST TUESDAYS WEATHER: Sunny and High of 5°C MOON: Waxing half Friday, March 22, 2002 Issue 88.7 WWW.MATHNEWS.UWATERLOO.CA Everything you UPDATED didnt want to know about BIWEEKLY math. PRETZEL THOUSANDS KILLED IN SASKATCHEWAN REGINA Thousands of ground-hogs have been killed in a cross-province hunting derby. Wildlife groups are encouraging farmers to shoot the animals instead of using a chemical SHOP poison or other method of pest con- trol. Yet, other wildlife groups are concerned about the possibility of too many groundhogs being killed, putting groundhogs on the endan- gered species list. CLONES CLONE CLONES CLONE HELSINKI Cloned Finnish scientists BUYS have succeeded in becoming the first clones to create a clone of a clones clone. The mouse, a clone of a mouse cloned in Hawaii last year, is not ad- justing well to the clone lifestyle. Cheezor, as the clonologists call her, has difficulty walking, eating, CN and not crawling over the side of tables. The cloned scientists, al- though proud of their achievement, regret not having watched Multiplic- From Waterloo snack ity before beginning their work. start-up to multinational INDONESIAN ISLANDS STOLEN JAKARTA Police have no idea how in 4 months: Page 23 over 200 Indonesian islands could have disappeared. We know they havent been gone long, said one inspector, I just went to Mataram on West Nusa Tenggara to visit relatives last week. Their only suspect is a woman in red travelling under the name Carmen SanDiego. Wed bring her in for questioning, but we dont know where in the world she is now, police reported. -

The Kent Brewery Building at 197 Ann Street

Evaluation of Cultural Heritage Value or Interest: The Kent Brewery building at 197 Ann Street 1.0 Background 1.1 Property Location The property at 197 Ann Street is located on the south side of Ann Street east of St. George Street (Appendix A). The property at 197 Ann St. consists of a two-storey main building (the Kent Brewery building), the adjoining one-storey brewery washhouse, a side garage, and three storage/garage outposts that extend to the back of the property. 1.2 Cultural Heritage Status The property at 197 Ann Street was added to the Inventory of Heritage Resources in 1997. In 2007, the Inventory of Heritage Resources was adopted in its entirety as the Register pursuant to Section 27 of the Ontario Heritage Act by Municipal Council. The property at 197 Ann Street is a potential cultural heritage resource. 1.3 Description The Old Kent Brewery at 197 Ann St is a two-storey former industrial building built for purpose as a proto-industrial mid-19th century brewery (Appendix B). It has the simple spare lines and square form of the Georgian style which was eminently suited to its utilitarian and vernacular function. It adheres to the Georgian style with its simplicity: the flat planes of its façade and side walls and the symmetry in the placement of the windows. The symmetry of the façade is broken by the side placement of the front door which allowed more space inside for production activities. This building is clad in locally-sourced London buff brick and an Italianate influence can be seen in the construction of an elaborate and corbelled brick cornice above. -

®°Ra, NFL • Pg 21 Careers & 0Pp0rt — - "Pportun|T|Es the Meliorist | Thursday, 2 December 2004 Page 02 Careers and Opportunities 29Ijinujioqqobfi6 219916)

Student Newspaper of The University of Lethbridge < Volume 38 Issue 13 < www.themeliorist.com < Thursday, 2 December, 2004 Check out some of this week's main n JmmmmWT mis! -mmmmmm features i % /m ojrA- J HL; '. Free Food i Pg-6 j m fa*,/ Art Gallery Pi V^ Pg-11 */jj^ * • • * / / I 1 -iV Artist Showcase Pg-17 '1 in Laden Slain in Calg ary Horns B-ball Pg-20 See related article on page 12 Index News • Pg 4 Entertainment • Pg 9 ^jjSgBfijaiBffiSS Sports-Pg 19 Maude Barlow - Pg 4 Futon Contest Winner Pg 14 ®°ra, NFL • Pg 21 Careers & 0pp0rt — - "pPOrtun|t|es The Meliorist | Thursday, 2 December 2004 Page 02 careers and opportunities 29iJinuJioqqobfi6 219916) in our office. Keep in mind the following arc just the ones scut Area (Jan. 15th) JOBS, JOBS, JOBS!!! specifically to our office. There arc many more on the Web site. - AB Sustainable Resource Development - Junior Forest Ran» Program: Crew Supervisors (Jan. 31st); Cooks (March 31st); Where did the semester go?? Only one week left of classes! DEADLINES are in brackets. ASAP means they may Participants (April 5th) But we'll be here until Dec. 24th. If you need any help with your hire the first qualified person who applies - DON'T - Federal Student Work Experience Program (FSWEP), across job search or career planning, be sure to come in and see us. Canada. Summer positions. Some excellent positions have WAIT! deadlines! Go to the Web site: jobs.gc.ca Career & Employment Services is a student service office ON-CAMPUS RECRUITING (OCR) dedicated to assist you in your job search and career planning. -

Fifty Years Young, with a Rich Future Ahead

Article from: The Actuary Magazine April / May 2015 – Volume 12, Issue 2 The Canadian Institute of Actuaries FIFTY YEARS YOUNG, WITH A RICH FUTURE AHEAD BY JACQUES TREMBLAY 1965 WAS A very interesting year. The Beatles’ “Eight Days a Week” topped Billboard’s Hot 100 in March. The most popular movie was “The Sound of Music.” Sean Connery was still James Bond. Actuaries used slide rules (and slide rule Actuarial thought and practice have a While Senator McCutcheon’s bill was being holsters!) as the microchip revolution long history in Canada. The beginning debated, there were approximately 300 was years away. Lester B. Pearson was of the actuarial profession in Canada fellows and 150 associates in Canada. The Canada’s prime minister and introduced can be dated in 1847, when the vast majority of these professionals were the country’s controversial new flag. The Canada Life Insurance Company was trained through the educational facilities of Source by James Michener was the best- founded in Hamilton, Ontario, by American actuarial organizations. Today more selling book that year. Hugh Baker, who became a Fellow than 4,800 members are proud to hold the of the Institute of Actuaries in 1852. FCIA and ACIA designations. In terms of the Not exciting enough? On March 18, 1965, The federal Department of Insurance Society of Actuaries (SOA), 4,377 FCIA and federal Senate Bill S-45 was given Royal was established in 1875 and shortly ACIA holders also carry SOA designations: Assent, thus creating the Canadian Institute thereafter recruited actuaries to its ACIA and ASA, 939; ACIA and FSA, 140; FCIA of Actuaries (CIA). -

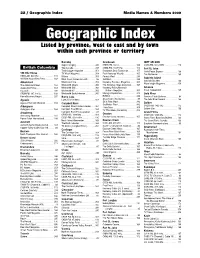

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm: a History of Corporate Ownership in Canada

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: A History of Corporate Governance around the World: Family Business Groups to Professional Managers Volume Author/Editor: Randall K. Morck, editor Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-53680-7 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/morc05-1 Conference Date: June 21-22, 2003 Publication Date: November 2005 Title: The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm: A History of Corporate Ownership in Canada Author: Randall Morck, Michael Percy, Gloria Tian, Bernard Yeung URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10268 1 The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm A History of Corporate Ownership in Canada Randall K. Morck, Michael Percy, Gloria Y. Tian, and Bernard Yeung 1.1 Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century, large pyramidal corporate groups, controlled by wealthy families or individuals, dominated Canada’s large corporate sector, as in modern continental European countries. Over several decades, a large stock market, high taxes on inherited income, a sound institutional environment, and capital account openness accompa- nied the rise of widely held firms. At mid-century, the Canadian large cor- porate sector was primarily freestanding widely held firms, as in the mod- ern large corporate sectors of the United States and United Kingdom. Then, in the last third of the century, a series of institutional changes took place. These included a more bank-based financial system, a sharp abate- Randall K. Morck is Stephen A. Jarislowsky Distinguished Professor of Finance at the University of Alberta School of Business and a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research.