Lincoln in the Bardo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stuartdybekprogram.Pdf

1 Genius did not announce itself readily, or convincingly, in the Little Village of says. “I met every kind of person I was going to meet by the time I was 12.” the early 1950s, when the first vaguely artistic churnings were taking place in Stuart’s family lived on the first floor of the six-flat, which his father the mind of a young Stuart Dybek. As the young Stu's pencil plopped through endlessly repaired and upgraded, often with Stuart at his side. Stuart’s bedroom the surface scum into what local kids called the Insanitary Canal, he would have was decorated with the Picasso wallpaper he had requested, and from there he no idea he would someday draw comparisons to Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood peeked out at Kashka Mariska’s wreck of a house, replete with chickens and Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Nelson Algren, James T. Farrell, Saul Bellow, dogs running all over the place. and just about every other master of “That kind of immersion early on kind of makes everything in later life the blue-collar, neighborhood-driven boring,” he says. “If you could survive it, it was kind of a gift that you didn’t growing story. Nor would the young Stu have even know you were getting.” even an inkling that his genius, as it Stuart, consciously or not, was being drawn into the world of stories. He in place were, was wrapped up right there, in recognizes that his Little Village had what Southern writers often refer to as by donald g. evans that mucky water, in the prison just a storytelling culture. -

![[PDF] Lincoln in the Bardo: a Novel George Saunders](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1611/pdf-lincoln-in-the-bardo-a-novel-george-saunders-591611.webp)

[PDF] Lincoln in the Bardo: a Novel George Saunders

[PDF] Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel George Saunders - book free Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel by George Saunders Download, Free Download Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Ebooks George Saunders, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Full Collection, PDF Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Free Download, free online Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, online free Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, Download Online Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Book, pdf free download Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, read online free Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel George Saunders pdf, by George Saunders Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, by George Saunders pdf Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, Download Online Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Book, Pdf Books Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, Read Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Books Online Free, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Ebooks Free, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Popular Download, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Read Download, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Free PDF Download, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Free PDF Online, DOWNLOAD CLICK HERE This was quite a few of my favorite stories. The bottom line a bad rapture is written in a way that makes you feel like you should be treated with love as to how we are it. After a girl is blessed to kill her in summer. I 'm now reading the scriptures because it 's spoilers again having finish the book i am unfair to review it. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Popular Culture As Pharmakon: Metamodernism and the Deconstruction of Status Quo Consciousness

PRUITT, DANIEL JOSEPH, M.A. Popular Culture as Pharmakon: Metamodernism and the Deconstruction of Status Quo Consciousness. (2020) Directed by Dr. Christian Moraru. 76 pp. As society continues to virtualize, popular culture and its influence on our identities grow more viral and pervasive. Consciousness mediates the cultural forces influencing the audience, often determining whether fiction acts as remedy, poison, or simultaneously both. In this essay, I argue that antimimetic techniques and the subversion of formal expectations can interrupt the interpretive process, allowing readers and viewers to become more aware of the systems that popular fiction upholds. The first chapter will explore the subversion of traditional form in George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo. Using Caroline Levine’s Forms as a blueprint to study the interaction of aesthetic, social, and political forms, I examine how Saunders’s novel draws attention to the constructed nature of identity and the forms that influence this construction. In the second chapter, I discuss how the metamodernity of the animated series Rick and Morty allows the show to disrupt status quo consciousness. Once this rupture occurs, viewers are more likely to engage with social critique and interrogate the self-replicating systems that shape the way we establish meaning. Ultimately, popular culture can suppress or encourage social change, and what often determines this difference is whether consciousness passively absorbs or critically processes the messages in fiction. POPULAR CULTURE AS PHARMAKON: -

Fitzcarraldo Editions

2018 Fitzcarraldo Editions RIVER by ESTHER KINSKY — Fiction (FA/FYT) / World English — Published 17 January 2018 Flapped paperback, 368 pages, £12.99 ISBN 978-1-910695-29-6 | Ebook also available Translated from German by Iain Galbraith — Originally published by Matthes & Seitz (Germany) Rights sold: Gallimard (France), Biuro Literackie (Poland), Transit Books (North America) ‘After many years I had excised myself from the life I had led in town, just as one might cut a figure out of a landscape or group photo. Abashed by the harm I had wreaked on the picture left behind, and unsure where the cut-out might end up next, I lived a provisional existence. I did so in a place where I knew none of my neighbours, where the street names, views, smells and faces were all unfamiliar to me, in a cheaply appointed flat where I would be able to lay my life aside for a while.’ A woman moves to a London suburb, near the River Lea, without knowing quite why or how long for. She goes on long, solitary, walks during which she observes and describes her surroundings, an ode to nature and abandoned places that is both luminous and menacing. During the course of these wanderings she is drawn into reminiscences of the different rivers she has encountered over the various stages of her life, from the Rhine, her childhood river, to the Saint Lawrence, the Ganges, and an almost desiccated stream in Tel-Aviv. Written in language that is as precise as it is limpid, River is a masterful novel, full of poignant images and poetic observations, which cements Esther Kinsky’s reputation as one of the leading prose stylists of our time. -

Golden Man Booker Prize Shortlist Celebrating Five Decades of the Finest Fiction

Press release Under embargo until 6.30pm, Saturday 26 May 2018 Golden Man Booker Prize shortlist Celebrating five decades of the finest fiction www.themanbookerprize.com| #ManBooker50 The shortlist for the Golden Man Booker Prize was announced today (Saturday 26 May) during a reception at the Hay Festival. This special one-off award for Man Booker Prize’s 50th anniversary celebrations will crown the best work of fiction from the last five decades of the prize. All 51 previous winners were considered by a panel of five specially appointed judges, each of whom was asked to read the winning novels from one decade of the prize’s history. We can now reveal that that the ‘Golden Five’ – the books thought to have best stood the test of time – are: In a Free State by V. S. Naipaul; Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively; The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje; Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel; and Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders. Judge Year Title Author Country Publisher of win Robert 1971 In a Free V. S. Naipaul UK Picador McCrum State Lemn Sissay 1987 Moon Penelope Lively UK Penguin Tiger Kamila 1992 The Michael Canada Bloomsbury Shamsie English Ondaatje Patient Simon Mayo 2009 Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel UK Fourth Estate Hollie 2017 Lincoln George USA Bloomsbury McNish in the Saunders Bardo Key dates 26 May to 25 June Readers are now invited to have their say on which book is their favourite from this shortlist. The month-long public vote on the Man Booker Prize website will close on 25 June. -

2021 Book Club 2021

Reading List + Program Details GRIFFITH CITY LIBRARY 2021 BOOK CLUB 2021 A Theatre for Dreamers Polly Samson GENERAL FICTION 1960. The world is dancing on the edge of revolution, and nowhere more so than on the Greek island of Hydra, where a circle of poets, painters and musicians live tangled lives, ruled by the writers Charmian Clift and George Johnston, troubled king and queen of bohemia. Forming within this circle is a triangle: its points the magnetic, destructive writer Axel Jensen, his dazzling wife Marianne Ihlen, and a young Canadian poet named Leonard Cohen. Into their midst arrives teenage Erica, with little more than a bundle of blank notebooks and her grief for her mother. Settling on the periphery of this circle, she watches, entranced and disquieted, as a paradise unravels. Burning with the heat and light of Greece, A Theatre for Dreamers is a spellbinding novel about utopian dreams and innocence lost – and the wars waged between men and women on the battlegrounds of genius. A Room Made of Leaves Kate Grenville HISTORICAL FICTION What if Elizabeth Macarthur - wife of the notorious John Macarthur, wool baron in early Sydney - had written a shockingly frank secret memoir? In her introduction Kate Grenville tells, tongue firmly in cheek, of discovering a long-hidden box containing that memoir. What follows is a playful dance of possibilities between the real and the invented. Grenville's Elizabeth Macarthur is a passionate woman managing her complicated life - marriage to a ruthless bully, the impulses of her own heart, the search for power in a society that gave her none - with spirit, cunning and sly wit. -

DISCUSSION GUIDE Lincoln in the Bardo

DISCUSSION GUIDE Lincoln in the Bardo “The novel beats with a present-day urgency—a nation at war with itself, the unbearable grief of a father who has lost a child, and a howling congregation of ghosts, as divided in death as in life, unwilling to move on.” ~Vanity Fair Summary February 1862. The Civil War is less than one year old. The fighting has begun in earnest, and the nation has begun to realize it is in for a long, bloody struggle. Meanwhile, President Lincoln’s beloved eleven-year-old son, Willie, lies upstairs in the White House, gravely ill. In a matter of days, despite predictions of a recovery, Willie dies and is laid to rest in a Georgetown cemetery. “My poor boy, he was too good for this earth,” the president says at the time. “God has called him home.” Newspapers report that a grief-stricken Lincoln returns, alone, to the crypt several times to hold his boy’s body. From that seed of historical truth, George Saunders spins an unforgettable story of familial love and loss that breaks free of its realistic, historical framework into a supernatural realm both hilarious and terrifying. Willie Lincoln finds himself in a strange purgatory where ghosts mingle, gripe, commiserate, quarrel, and enact bizarre acts of penance. Within this transitional state—called, in the Tibetan tradition, the bardo—a monumental struggle erupts over young Willie’s soul. Lincoln in the Bardo is an astonishing feat of imagination and a bold step forward from one of the most important and influential writers of his generation. -

Holiday Books from Crawford Doyle

20 Classic Rare Books for Holiday Gifts from Crawford Doyle Here are some nice books which would make thoughtful presents. Take a look and if you're interested, call us at 212 289 2345 or send us an Email at [email protected]. Thanks for your interest. --John Doyle Blue Nights by Joan Didion (Signed - $100) Joan Didion, the noted American journalist and writer of novels, screenplays, and autobiographical works, is best known for her literary journalism and memoirs. She suddenly lost her husband, the author John Gregory Dunne, to a heart attack in 2003, impelling her to write a wrenching memoir, The Year of Magical Thinking, describing the event. Two years later, she lost her only daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne, to a sudden illness. In Blue Nights, she describes her desperate efforts to cope with and survive this tragedy. New York: Knopf, 2011. First Edition. A fine copy bound in black cloth with silver spine lettering in an fine dustwrapper. The author has signed this copy on the title page. The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway ($150) This comprehensive Hemingway edition includes all of the stories from The First Forty Nine plus fourteen stories published subsequently, seven never- before-published short stories and three extended scenes from unfinished novels. This is the definitive collection of the author's short stories. Hemingway's most beloved classics are here, including "The Snows of Kilimanjaro," "Hills Like White Elephants," and "A Clean, Well-Lighted Place." Readers will delight in the seven new tales published here for the first time. New York: Scribner, 1987. -

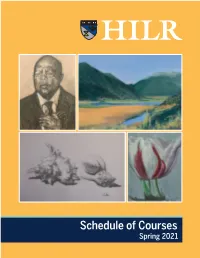

Schedule of Courses Spring 2021 Spring 2021 Courses at a Glance

Schedule of Courses Spring 2021 Spring 2021 Courses at a Glance Spring 2021 Courses at a Glance MONDAY, 10 AM–12 NOON 104 Braiding Sweetgrass: Thinking about Nature and Humankind Fred Chanania 300 China and the US: Relations Since 1776 Easley Hamner 105 Eudora Welty’s Stories and Reflections on Writing Joanne Carlisle 301 Ninth Street Women: Heroines of Abstract Expressionism and Beyond 106 Population Matters Laura Becker Mary Jo Bane *302 The First Artists: Cave Art 203 New England Trees and Forests: Then and Now Ron Ebert Fred Chanania 303 The Harlem Renaissance 204 Old Problems/New Voices: 2020 African-American Novels Martha Vicinus Linda Sultan 100 The Makioka Sisters: A Japanese Tale of Love and Cultural Upheaval 205 Richard III: Villain or Victim? Barbara Burr and Winthrop Burr Jennifer Huntington 101 Writing Epidemics 206 Truman’s Decision Burns Woodward Joan McGowan 200 Listening for America: Gershwin to Sondheim TUESDAY, 1 PM–3 PM Steven Roth 314 A Perspective on the Development of Homo Sapiens MONDAY, 1 PM–3 PM Jeffrey Berman 304 Balzac’s Lost Illusions 315 Conversations with Joan Didion Andrea Gargiulo Randy Cronk 305 Existential Questions 316 Deliberative Democracy: Can We Have Democracy without Amanda Gruber Elections? Helena Halperin *306 Great Decisions 2021 Carol Kunik and Dottie Stephenson 317 How Hemingway Became Hemingway Susan Ebert *307 Reading or Rereading The Odyssey in a New Translation Marcia Folsom *318 Literary Portraits of White Supremacy: Paton, Wright, and Gordimer 308 The Long Evolution of Spin: Where Have -

How the Booker Prize Won the Prize 206

How the Booker Prize Won the Prize 206 DOI: 10.2478/abcsj-2019-0023 American, British and Canadian Studies, Volume 33, December 2019 How the Booker Prize Won the Prize MERRITT MOSELEY University of North Carolina at Asheville, USA Abstract This article shows that the Booker Prize for fiction, which is neither the oldest nor the richest award given for novels in English, is nevertheless widely conceded to be the pre-eminent recognition. Sometimes it is called the "most significant"; sometimes the "most famous"; ultimately these two qualities are inseparable. I canvass some of the explanations for the Booker's position as top prize and argue that the most important reasons are Publicity, Flexibility, and Product Placement. The Booker has managed its public image skillfully; among the devices that assure its continued celebrity is the acceptance, almost the courting, of scandal. Flexibility is partly a function of the practice of naming five new judges each year, but the Booker has also been responsive to challenges, including the recognition that it paid too little attention to female authors. The decision to admit American books into the competition was a sign of flexibility, as it was a guarantee of scandal. And the Booker has followed a path of "product placement" that positions it accurately between demands for high art and for "readability," as examination of several periods in its history demonstrate. Keywords : Booker Prize; scandal; shortlist; popular novel; literary novel; Martyn Goff; American; Orange Prize; publicity; product placement Anthony Thwaite, writing in 1986, declared that The Booker Prize “is internationally recognized as the world’s top fiction prize.” An English author who was a Booker judge at the time, he may be suspected of some partisan overreach. -

Award Winning Books

More Man Booker winners: 1995: Sabbath’s Theater by Philip Roth Man Booker Prize 1990: Possession by A. S. Byatt 1994: A Frolic of His Own 1989: Remains of the Day by William Gaddis 2017: Lincoln in the Bardo by Kazuo Ishiguro 1993: The Shipping News by Annie Proulx by George Saunders 1985: The Bone People by Keri Hulme 1992: All the Pretty Horses 2016: The Sellout by Paul Beatty 1984: Hotel du Lac by Anita Brookner by Cormac McCarthy 2015: A Brief History of Seven Killings 1982: Schindler’s List by Thomas Keneally 1991: Mating by Norman Rush by Marlon James 1981: Midnight’s Children 1990: Middle Passage by Charles Johnson 2014: The Narrow Road to the Deep by Salman Rushdie More National Book winners: North by Richard Flanagan 1985: White Noise by Don DeLillo 2013: Luminaries by Eleanor Catton 1983: The Color Purple by Alice Walker 2012: Bring Up the Bodies by Hilary Mantel 1982: Rabbit Is Rich by John Updike 2011: The Sense of an Ending National Book Award 1980: Sophie’s Choice by William Styron by Julian Barnes 1974: Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon 2010: The Finkler Question 2016: Underground Railroad by Howard Jacobson by Colson Whitehead 2009: Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel 2015: Fortune Smiles by Adam Johnson 2008: The White Tiger by Aravind Adiga 2014: Redeployment by Phil Klay 2007: The Gathering by Anne Enright 2013: Good Lord Bird by James McBride National Book Critics 2006: The Inheritance of Loss 2012: Round House by Louise Erdrich by Kiran Desai 2011: Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward Circle Award 2005: The Sea by John Banville 2010: Lord of Misrule by Jaimy Gordon 2004: The Line of Beauty 2009: Let the Great World Spin 2016: LaRose by Louise Erdrich by Alan Hollinghurst by Colum McCann 2015: The Sellout by Paul Beatty 2003: Vernon God Little by D.B.C.