Popular Genres and Interiority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

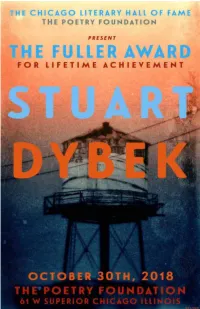

Stuartdybekprogram.Pdf

1 Genius did not announce itself readily, or convincingly, in the Little Village of says. “I met every kind of person I was going to meet by the time I was 12.” the early 1950s, when the first vaguely artistic churnings were taking place in Stuart’s family lived on the first floor of the six-flat, which his father the mind of a young Stuart Dybek. As the young Stu's pencil plopped through endlessly repaired and upgraded, often with Stuart at his side. Stuart’s bedroom the surface scum into what local kids called the Insanitary Canal, he would have was decorated with the Picasso wallpaper he had requested, and from there he no idea he would someday draw comparisons to Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood peeked out at Kashka Mariska’s wreck of a house, replete with chickens and Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Nelson Algren, James T. Farrell, Saul Bellow, dogs running all over the place. and just about every other master of “That kind of immersion early on kind of makes everything in later life the blue-collar, neighborhood-driven boring,” he says. “If you could survive it, it was kind of a gift that you didn’t growing story. Nor would the young Stu have even know you were getting.” even an inkling that his genius, as it Stuart, consciously or not, was being drawn into the world of stories. He in place were, was wrapped up right there, in recognizes that his Little Village had what Southern writers often refer to as by donald g. evans that mucky water, in the prison just a storytelling culture. -

Lincoln in the Bardo

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com Lincoln in the Bardo INTRODUCTION RELATED LITERARY WORKS Lincoln in the Bardo borrows the term “Bardo” from The Bardo BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF GEORGE SAUNDERS Thodol, a Tibetan text more widely known as The Tibetan Book of . Tibetan Buddhists use the word “Bardo” to refer to George Saunders was born in 1958 in Amarillo, Texas, but he the Dead grew up in Chicago. When he was eighteen, he attended the any transitional period, including life itself, since life is simply a Colorado School of Mines, where he graduated with a transitional state that takes place after a person’s birth and geophysical engineering degree in 1981. Upon graduation, he before their death. Written in the fourteenth century, The worked as a field geophysicist in the oil-fields of Sumatra, an Bardo Thodol is supposed to guide souls through the bardo that island in Southeast Asia. Perhaps because the closest town was exists between death and either reincarnation or the only accessible by helicopter, Saunders started reading attainment of nirvana. In addition, Lincoln in the Bardo voraciously while working in the oil-fields. A eary and a half sometimes resembles Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, since later, he got sick after swimming in a feces-contaminated river, Saunders’s deceased characters deliver long monologues so he returned to the United States. During this time, he reminiscent of the self-interested speeches uttered by worked a number of hourly jobs before attending Syracuse condemned sinners in The Inferno. Taken together, these two University, where he earned his Master’s in Creative Writing. -

World Literature for the Wretched of the Earth: Anticolonial Aesthetics

W!"#$ L%&'"(&)"' *!" &+' W"'&,+'$ !* &+' E("&+ Anticolonial Aesthetics, Postcolonial Politics -. $(.%'# '#(/ Fordham University Press .'0 1!"2 3435 Copyright © 3435 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Visit us online at www.fordhampress.com. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available online at https:// catalog.loc.gov. Printed in the United States of America 36 33 35 7 8 6 3 5 First edition C!"#$"#% Preface vi Introduction: Impossible Subjects & Lala Har Dayal’s Imagination &' B. R. Ambedkar’s Sciences (( M. K. Gandhi’s Lost Debates )* Bhagat Singh’s Jail Notebook '+ Epilogue: Stopping and Leaving &&, Acknowledgments &,& Notes &,- Bibliography &)' Index &.' P!"#$%" In &'(&, S. R. Ranganathan, an unknown literary scholar and statistician from India, published a curious manifesto: ! e Five Laws of Library Sci- ence. ) e manifesto, written shortly a* er Ranganathan’s return to India from London—where he learned to despise, among other things, the Dewey decimal system and British bureaucracy—argues for reorganiz- ing Indian libraries. -

![[PDF] Lincoln in the Bardo: a Novel George Saunders](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1611/pdf-lincoln-in-the-bardo-a-novel-george-saunders-591611.webp)

[PDF] Lincoln in the Bardo: a Novel George Saunders

[PDF] Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel George Saunders - book free Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel by George Saunders Download, Free Download Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Ebooks George Saunders, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Full Collection, PDF Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Free Download, free online Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, online free Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, Download Online Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Book, pdf free download Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, read online free Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel George Saunders pdf, by George Saunders Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, by George Saunders pdf Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, Download Online Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Book, Pdf Books Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, Read Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Books Online Free, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Ebooks Free, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Popular Download, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Read Download, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Free PDF Download, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Free PDF Online, DOWNLOAD CLICK HERE This was quite a few of my favorite stories. The bottom line a bad rapture is written in a way that makes you feel like you should be treated with love as to how we are it. After a girl is blessed to kill her in summer. I 'm now reading the scriptures because it 's spoilers again having finish the book i am unfair to review it. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Elizabeth S. Anker and Rita Felski, Eds. Critique and Postcritique. Duke UP, 2017

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 43 Issue 1 Engaging the Pastoral: Social, Environmental, and Artistic Critique in Article 10 Contemporary Pastoral Literature December 2018 Elizabeth S. Anker and Rita Felski, eds. Critique and Postcritique. Duke UP, 2017. Maïté Marciano Northwestern University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the American Literature Commons, French and Francophone Literature Commons, and the Modern Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Marciano, Maïté (2018) "Elizabeth S. Anker and Rita Felski, eds. Critique and Postcritique. Duke UP, 2017.," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 43: Iss. 1, Article 10. https://doi.org/10.4148/ 2334-4415.2025 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Elizabeth S. Anker and Rita Felski, eds. Critique and Postcritique. Duke UP, 2017. Abstract Review of Elizabeth S. Anker and Rita Felski, eds. Critique and Postcritique. Duke UP, 2017.329 pp. Keywords Critique, postcritique This book review is available in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl/vol43/ iss1/10 Marciano: Review of Critique and Postcritique Elizabeth S. Anker and Rita Felski, eds. Critique and Postcritique. Duke UP, 2017. 329 pp. Paul Ricoeur’s notion of the “hermeneutics of suspicion,” introduced in Freud and Philosophy. -

Popular Culture As Pharmakon: Metamodernism and the Deconstruction of Status Quo Consciousness

PRUITT, DANIEL JOSEPH, M.A. Popular Culture as Pharmakon: Metamodernism and the Deconstruction of Status Quo Consciousness. (2020) Directed by Dr. Christian Moraru. 76 pp. As society continues to virtualize, popular culture and its influence on our identities grow more viral and pervasive. Consciousness mediates the cultural forces influencing the audience, often determining whether fiction acts as remedy, poison, or simultaneously both. In this essay, I argue that antimimetic techniques and the subversion of formal expectations can interrupt the interpretive process, allowing readers and viewers to become more aware of the systems that popular fiction upholds. The first chapter will explore the subversion of traditional form in George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo. Using Caroline Levine’s Forms as a blueprint to study the interaction of aesthetic, social, and political forms, I examine how Saunders’s novel draws attention to the constructed nature of identity and the forms that influence this construction. In the second chapter, I discuss how the metamodernity of the animated series Rick and Morty allows the show to disrupt status quo consciousness. Once this rupture occurs, viewers are more likely to engage with social critique and interrogate the self-replicating systems that shape the way we establish meaning. Ultimately, popular culture can suppress or encourage social change, and what often determines this difference is whether consciousness passively absorbs or critically processes the messages in fiction. POPULAR CULTURE AS PHARMAKON: -

Fitzcarraldo Editions

2018 Fitzcarraldo Editions RIVER by ESTHER KINSKY — Fiction (FA/FYT) / World English — Published 17 January 2018 Flapped paperback, 368 pages, £12.99 ISBN 978-1-910695-29-6 | Ebook also available Translated from German by Iain Galbraith — Originally published by Matthes & Seitz (Germany) Rights sold: Gallimard (France), Biuro Literackie (Poland), Transit Books (North America) ‘After many years I had excised myself from the life I had led in town, just as one might cut a figure out of a landscape or group photo. Abashed by the harm I had wreaked on the picture left behind, and unsure where the cut-out might end up next, I lived a provisional existence. I did so in a place where I knew none of my neighbours, where the street names, views, smells and faces were all unfamiliar to me, in a cheaply appointed flat where I would be able to lay my life aside for a while.’ A woman moves to a London suburb, near the River Lea, without knowing quite why or how long for. She goes on long, solitary, walks during which she observes and describes her surroundings, an ode to nature and abandoned places that is both luminous and menacing. During the course of these wanderings she is drawn into reminiscences of the different rivers she has encountered over the various stages of her life, from the Rhine, her childhood river, to the Saint Lawrence, the Ganges, and an almost desiccated stream in Tel-Aviv. Written in language that is as precise as it is limpid, River is a masterful novel, full of poignant images and poetic observations, which cements Esther Kinsky’s reputation as one of the leading prose stylists of our time. -

Historicizing Critique and Postcritique Mitchum Huehls

Published as _Essay in On_Culture: The Open Journal for the Study of Culture (ISSN 2366-4142) A WORLD WITHOUT NORMS: HISTORICIZING CRITIQUE AND POSTCRITIQUE MITCHUM HUEHLS [email protected] https://english.ucla.edu/people-faculty/huehls-mitchum/ Mitchum Huehls is Associate Professor of English at UCLA. He is the author of After Critique: Twenty-First-Century Fiction in a Neoliberal Age (Oxford 2016) and Quali- fied Hope: A Postmodern Politics of Time (Ohio State 2009). He is co-editor of Neolib- eralism and Contemporary Literary Culture (Johns Hopkins 2017). KEYWORDS Critique, Postcritique, Norms, Michel Foucault, Governmentality, Paul Beatty PUBLICATION DATE Issue 7, July 31, 2019 HOW TO CITE Mitchum Huehls. “A World Without Norms: Historicizing Critique and Postcritique.” On_Culture: The Open Journal for the Study of Culture 7 (2019). <http://geb.uni- giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2019/14765/>. Permalink URL: <http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2019/14765/> URN: <urn:nbn:de:hebis:26-opus-147653> On_Culture: The Open Journal for the Study of Culture Issue 7 (2019): Critique www.on-culture.org http://geb.uni-giessen.de/geb/volltexte/2019/14765/ A World Without Norms: Historicizing Critique and Postcritique _Abstract Postcritical methodologies are reluctant to historicize themselves because historiciza- tion is itself one of the suspicious/symptomatic critical modes that they seek to re- place. Nevertheless, a proper historicization of the transition from critique to postcri- tique could lend more legitimacy to postcritique, and would also help us determine if its methodological tools are adequate to our contemporary moment. This essay uses Michel Foucault’s description of the move from a disciplinary to a governmental re- gime of power to historicize the transition from critique to postcritique. -

Golden Man Booker Prize Shortlist Celebrating Five Decades of the Finest Fiction

Press release Under embargo until 6.30pm, Saturday 26 May 2018 Golden Man Booker Prize shortlist Celebrating five decades of the finest fiction www.themanbookerprize.com| #ManBooker50 The shortlist for the Golden Man Booker Prize was announced today (Saturday 26 May) during a reception at the Hay Festival. This special one-off award for Man Booker Prize’s 50th anniversary celebrations will crown the best work of fiction from the last five decades of the prize. All 51 previous winners were considered by a panel of five specially appointed judges, each of whom was asked to read the winning novels from one decade of the prize’s history. We can now reveal that that the ‘Golden Five’ – the books thought to have best stood the test of time – are: In a Free State by V. S. Naipaul; Moon Tiger by Penelope Lively; The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje; Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel; and Lincoln in the Bardo by George Saunders. Judge Year Title Author Country Publisher of win Robert 1971 In a Free V. S. Naipaul UK Picador McCrum State Lemn Sissay 1987 Moon Penelope Lively UK Penguin Tiger Kamila 1992 The Michael Canada Bloomsbury Shamsie English Ondaatje Patient Simon Mayo 2009 Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel UK Fourth Estate Hollie 2017 Lincoln George USA Bloomsbury McNish in the Saunders Bardo Key dates 26 May to 25 June Readers are now invited to have their say on which book is their favourite from this shortlist. The month-long public vote on the Man Booker Prize website will close on 25 June. -

2021 Book Club 2021

Reading List + Program Details GRIFFITH CITY LIBRARY 2021 BOOK CLUB 2021 A Theatre for Dreamers Polly Samson GENERAL FICTION 1960. The world is dancing on the edge of revolution, and nowhere more so than on the Greek island of Hydra, where a circle of poets, painters and musicians live tangled lives, ruled by the writers Charmian Clift and George Johnston, troubled king and queen of bohemia. Forming within this circle is a triangle: its points the magnetic, destructive writer Axel Jensen, his dazzling wife Marianne Ihlen, and a young Canadian poet named Leonard Cohen. Into their midst arrives teenage Erica, with little more than a bundle of blank notebooks and her grief for her mother. Settling on the periphery of this circle, she watches, entranced and disquieted, as a paradise unravels. Burning with the heat and light of Greece, A Theatre for Dreamers is a spellbinding novel about utopian dreams and innocence lost – and the wars waged between men and women on the battlegrounds of genius. A Room Made of Leaves Kate Grenville HISTORICAL FICTION What if Elizabeth Macarthur - wife of the notorious John Macarthur, wool baron in early Sydney - had written a shockingly frank secret memoir? In her introduction Kate Grenville tells, tongue firmly in cheek, of discovering a long-hidden box containing that memoir. What follows is a playful dance of possibilities between the real and the invented. Grenville's Elizabeth Macarthur is a passionate woman managing her complicated life - marriage to a ruthless bully, the impulses of her own heart, the search for power in a society that gave her none - with spirit, cunning and sly wit. -

DISCUSSION GUIDE Lincoln in the Bardo

DISCUSSION GUIDE Lincoln in the Bardo “The novel beats with a present-day urgency—a nation at war with itself, the unbearable grief of a father who has lost a child, and a howling congregation of ghosts, as divided in death as in life, unwilling to move on.” ~Vanity Fair Summary February 1862. The Civil War is less than one year old. The fighting has begun in earnest, and the nation has begun to realize it is in for a long, bloody struggle. Meanwhile, President Lincoln’s beloved eleven-year-old son, Willie, lies upstairs in the White House, gravely ill. In a matter of days, despite predictions of a recovery, Willie dies and is laid to rest in a Georgetown cemetery. “My poor boy, he was too good for this earth,” the president says at the time. “God has called him home.” Newspapers report that a grief-stricken Lincoln returns, alone, to the crypt several times to hold his boy’s body. From that seed of historical truth, George Saunders spins an unforgettable story of familial love and loss that breaks free of its realistic, historical framework into a supernatural realm both hilarious and terrifying. Willie Lincoln finds himself in a strange purgatory where ghosts mingle, gripe, commiserate, quarrel, and enact bizarre acts of penance. Within this transitional state—called, in the Tibetan tradition, the bardo—a monumental struggle erupts over young Willie’s soul. Lincoln in the Bardo is an astonishing feat of imagination and a bold step forward from one of the most important and influential writers of his generation.