How the Booker Prize Won the Prize 206

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literary Awards 2018

Baileys Women’s Prize for Fiction The Golden Man Booker Home Fire (winner) 2018 marked the 50th year of the Man Kamila Shamsie Booker Prize for fiction. Of all the winning Isma, Aneeka and Parvaiz are novels over the years, one from each decade siblings from an immigrant was nominated for the shortlist. family in the UK. After their In a Free State (1971) by V.S. Naipul mother’s death Isma looked Moon Tiger (1987) by Penelope Lively after her brother and sister. The English Patient (1992) by Michael Now free to pursue her own Ondaatje dreams she can’t stop worrying about her Wolf Hall (2009) by Hilary Mantel sister who she left behind, or her brother Lincoln in the Bardo (2017) by George who has fled to pursue the jihadist legacy of Saunders a father they never knew. st From the shortlist, readers voted The English Sing, Unburied, Sing (finalist) Patient as their favourite. Jesmyn Ward The English Patient (winner) This is a novel of how far the bonds of family Michael Ondaatje stretch, particularly when they are tested by 1 Four lives cross paths in an poverty, drugs and race. With Italian villa at the end of a loving but mostly absent the Second World War. A mother, Jojo is a 13 year old boy looking for a role model. 2018 nurse, a soldier and a thief are all troubled by the past While he finds one in his of the English patient, a grandfather where does his man who has been burnt father, about to be released Literary beyond recognition who from prison, fit in? lies in the upstairs bedroom. -

Reflections on Some Recent Australian Novels ELIZABETH WEBBY

Books and Covers: Reflections on Some Recent Australian Novels ELIZABETH WEBBY For the 2002 Miles Franklin Award, given to the best Australian novel of the year, my fellow judges and I ended up with a short list of five novels. Three happened to come from the same publishing house – Pan Macmillan Australia – and we could not help remarking that much more time and money had been spent on the production of two of the titles than on the third. These two, by leading writers Tim Winton and Richard Flanagan, were hardbacks with full colour dust jackets and superior paper stock. Flanagan’s Gould’s Book of Fish (2001) also featured colour illustrations of the fish painted by Tasmanian convict artist W. B. Gould, the initial inspiration for the novel, at the beginning of each chapter, as well as changes in type colour to reflect the notion that Gould was writing his manuscript in whatever he could find to use as ink. The third book, Joan London’s Gilgamesh (2001), was a first novel, though by an author who had already published two prize- winning collections of short stories. It, however, was published in paperback, with a monochrome and far from eye-catching photographic cover that revealed little about the work’s content. One of the other judges – the former leading Australian publisher Hilary McPhee – was later quoted in a newspaper article on the Award, reflecting on what she described as the “under publishing” of many recent Australian novels. This in turn drew a response from the publisher of another of the short- listed novels, horrified that our reading of the novels submitted for the Miles Franklin Award might have been influenced in any way by a book’s production values. -

The Best According To

Books | The best according to... http://books.guardian.co.uk/print/0,,32972479299819,00.html The best according to... Interviews by Stephen Moss Friday February 23, 2007 Guardian Andrew Motion Poet laureate Choosing the greatest living writer is a harmless parlour game, but it might prove more than that if it provokes people into reading whoever gets the call. What makes a great writer? Philosophical depth, quality of writing, range, ability to move between registers, and the power to influence other writers and the age in which we live. Amis is a wonderful writer and incredibly influential. Whatever people feel about his work, they must surely be impressed by its ambition and concentration. But in terms of calling him a "great" writer, let's look again in 20 years. It would be invidious for me to choose one name, but Harold Pinter, VS Naipaul, Doris Lessing, Michael Longley, John Berger and Tom Stoppard would all be in the frame. AS Byatt Novelist Greatness lies in either (or both) saying something that nobody has said before, or saying it in a way that no one has said it. You need to be able to do something with the English language that no one else does. A great writer tells you something that appears to you to be new, but then you realise that you always knew it. Great writing should make you rethink the world, not reflect current reality. Amis writes wonderful sentences, but he writes too many wonderful sentences one after another. I met a taxi driver the other day who thought that. -

{PDF EPUB} the Bone People by Keri Hulme the Bone People by Keri Hulme

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Bone People by Keri Hulme The Bone People by Keri Hulme. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 6601033f381f1782 • Your IP : 116.202.236.252 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. The Bone People by Keri Hulme. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. -

From Alignment to Commitment: the Early Work of James Kelman

From Alignment to Commitment: The Early Work of James Kelman Terence Patrick Murphy James Kelman (© BBC, 2002) Abstract In Marxism and Literature (1977), Raymond Williams argues that writing is in an important sense always aligned. This sense of alignment, however, may be distinguished from a sense of chosen commitment,which is “conscious, active, and open.” Through a close analysis of the early work of the Scottish working-class writer James Kelman, this essay examines how an ideologically committed writer learned to refashion the dominant forms of novelistic discourse for his own political purposes. For Kelman, commitment in writing involves the recognition of the “distinction between dialogue and narrative as a summation of the political system.” This distinction was “simply another method of exclusion, of marginalizing and disenfranchising different peoples, cultures and communities,” Political commitment thus required Kelman to break successfully with the tradition of “‘working class authors’ who allowed ‘the voice’ of higher authority to control narrative, the place where the psychological drama occurred.” Copyright © 2007 by Terence Patrick Murphy and Cultural Logic, ISSN 1097-3087 Terence Patrick Murphy 2 . the relation between the language of the novelist — always in some measure an educated language, as it has to be if the full account is to be given, and the language of these newly described men and women — a familiar language, steeped in a place and in work; often different in profound as well as simple ways — and to the novelist consciously different — from the habits of education: the class, the method, the underlying sensibility. It isn’t only a matter of relating disparate idioms, though that technicality is how it often appears. -

Teaching the Novel BEFORE, During After

97 U NIT P LAN: T EACHING T HE B ROTHERS K ARAMAZOV Chapter / Pages Teaching strategy / Learning activity AP AUDIT ELEMENT(S): KNOWLEDGE What students should know actively: What students should be able to recognize: SKILLS What students should be able to do: HABITS What students should do habitually: 98 Works Appearing on Suggestion Lists for “Question 3” Advanced Placement English Literature & Composition Examination: 1971-2011 26 7 The Little Foxes Invisible Man All the King’s Men Middlemarch 22 All the Pretty Horses Pygmalion Wuthering Heights Candide A Tale of Two Cities The Crucible To the Lighthouse 18 Cry Beloved Country Twelfth Night Crime and Punishment Equus Typical American Jane Eyre Lord Jim The Women of Brewster Place 17 Madame Bovary 3 The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn The Mayor of Casterbridge Alias Grace Great Expectations The Portrait of a Lady An American Tragedy Heart of Darkness The Sound and the Fury The American The Tempest 16 The Bluest Eye King Lear Waiting for Godot The Bonesetter's Daughter Moby-Dick Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The Catcher in the Rye Daisy Miller 15 6 David Copperfield The Great Gatsby Bless Me, Ultima Emma A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man The Cherry Orchard A Farewell to Arms The Scarlet Letter Ethan Frome Gulliver’s Travels Going After Cacciato 14 Hamlet The Handmaid’s Tale The Awakening Hedda Gabler Hard Times 13 Macbeth Henry IV, Part I Their Eyes Were Watching God Major Barbara House Made of Dawn Medea The House of Mirth 12 The Merchant of Venice To Kill a Mockingbird Beloved Moll Flanders The Kite Runner Catch-22 Mrs Dalloway Long Day’s Journey into Night Light in August Murder in the Cathedral Lord of the Flies 11 The Piano Lesson Mansfield Park As I Lay Dying Pride and Prejudice Master Harold” . -

An Analysis of Racial Discrimination Potrayed in Peter Carey's Novel

AN ANALYSIS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION POTRAYED IN PETER CAREY’S NOVEL : A LONG WAY FROM HOME A THESIS BY ANNISA FITRI REG.NO 160721002 DEPARTEMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN2019 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AN ANALYSIS OF RACIAL DISCRIMINATION POTRAYED IN PETER CAREY’S NOVEL : A LONG WAY FROM HOME A THESIS BY ANNISA FITRI REG. NO. 160721002 SUPERVISOR CO-SUPERVISOR Dr.Siti Norma Nasution, M.Hum Dra. Diah Rahayu Pratma, M.Pd NIP. 195707201983032001 NIP. 195612141986012001 Submitted to Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Medan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sarjana Sastra From Department of English. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2019 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Accepted by the Board of Examiners in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of SarjanaSastra from the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara. The examination is held in Department of English Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara on. Dean of Faculty of Cultural Studies University of Sumatera Utara Dr. Budi Agustono, M.S. NIP. 19600805 198703 1 001 Board of Examiners Dr.Siti Norma Nasution, M.Hum ____________________ Rahmadsyah Rangkuti,MA.,Ph.D. ____________________ Dra. Hj. Swesana Mardia Lubis, M.Hum ____________________ UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA Approved by the Department of English, Faculty of Cultural Studies, University of Sumatera Utara (USU) Medan as thesis for The Sarjana Sastra Examination. Head, Secretary, Prof. T. SilvanaSinar, M.A., Ph.D. Rahmadsyah Rangkuti, M.A., Ph.D. NIP. 195409161980032003 NIP. 197502092008121002 UNIVERSITAS SUMATERA UTARA AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I,ANNISA FITRI, DECLARE THAT I AM THE SOLE AUTHOR OF THIS THESIS EXCEPT WHERE REFERENCE IS MADE IN THE TEXT OF THIS THESIS. -

Faculty and Staff Best Books of 2014

Faculty and Staff Best Books of 2014 The “rules” of the game were to answer the following question: What was the best book you read in 2014? It could be a new book, an old book, a re-read, or anything that fits the bill. Not all contributors explained their selections, but for those who did, their reasons for choosing the book are included here. Some contributed several of their favorites since choosing just one is too difficult. Books chosen by multiple faculty or staff members have been bolded. Many books are available through the Durham Tech Library, either on our shelves or through interlibrary loan. Just ask a library staff member for help requesting a book that we don’t currently have on the shelves. How can I find this book through Book Title/Author the Durham Tech library? Describe your book or what made it your best read… Request this title through OCLC Siege 13 / Tamas Dobozy interlibrary loan A re-read. Mind control, surveillance, oligarchy, and diminishing 1984 / George Orwell PR 6029 .R8 N5 1961 freedoms….need I say more? I listened to the book CD on my way back and forth to work, then A Beautiful Mind / Sylvia Nasar QA 29 .N25 N37 1998 watched the movie. (The movie wasn’t as good as the book) A Grown-Up Kind of Pretty / Joshilyn Jackson PS 3610 .A3525 G76 2012 A Stolen Life / Jaycee Dugard HV 6574 .U6 D84 2011 A super heavy read... This is an important novel about the immigrant experience in the U.S. -

KS4 Book Recommendations

KS4 Book Recommendations Young Adult Books The Art of Being Normal – Lisa Williamson The Book Thief – Marcus Zusak Mary’s Monster – Lita Judge The Sun is Also a Star – Nicola Yoon A Witch Alone – Ruth Warburton Moonrise – Sarah Crossan Scat – Carl Hiasson Where Monsters Lie – Polly Ho Yen Water Born – Rachel Ward Numbers – Rachel Ward Contagion – Teri Terry Satellite – Nick Lake 7 Days – Eve Ainsworth Piecing Me Together – Renee Watson If You Find Me – Emily Murdoch Simon vs the Homosapien Agenda – Becky Albertalli Saint Death – Marcus Sedgwick The Gender Game – Bella Forrest Pure – Julianna Baggott Indigo Donut – Patrice Lawrence At the Sign of the Sugared Plum – Mary Hooper Scythe – Neal Shusterman The Hate U Give – Angie Thomas How I Live Now – Meg Rosoff Reunion – Fred Uhlman KS4 Book Recommendations Adult Books The Poisonwood Bible – Barbara Kingsolver Small Island – Andrea Levy The English Patient – Michael Ondaatje Return of the Soldier – Rebecca West Never Let Me Go – Kazuo Ishiguro The Life of Pi – Yann Martel Bel Canto - Ann Patchett Room – Emma Donaghue The White Tiger – Aravind Adiga White Teeth – Zadie Smith Vernon God Little – D. B. C. Pierre Paddy Clark Ha Ha Ha – Roddy Doyle Things Fall Apart – Chinua Achebe A Thousand Splendid Suns/The Kite Runner/And the Mountains Echoed - Khaled Hosseini The Shock of the Fall – Nathan Filer The Tenderness of Wolves – Stef Penney The Help – Kathryn Stockett A Mercy – Toni Morrison Oranges are Not the Only Fruit – Jeanette Winterston A Short History of Tractors in Ukrainian – Marina Lewycka -

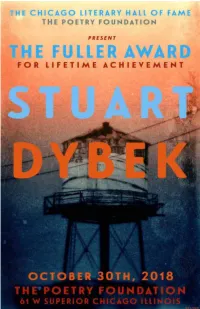

Stuartdybekprogram.Pdf

1 Genius did not announce itself readily, or convincingly, in the Little Village of says. “I met every kind of person I was going to meet by the time I was 12.” the early 1950s, when the first vaguely artistic churnings were taking place in Stuart’s family lived on the first floor of the six-flat, which his father the mind of a young Stuart Dybek. As the young Stu's pencil plopped through endlessly repaired and upgraded, often with Stuart at his side. Stuart’s bedroom the surface scum into what local kids called the Insanitary Canal, he would have was decorated with the Picasso wallpaper he had requested, and from there he no idea he would someday draw comparisons to Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood peeked out at Kashka Mariska’s wreck of a house, replete with chickens and Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Nelson Algren, James T. Farrell, Saul Bellow, dogs running all over the place. and just about every other master of “That kind of immersion early on kind of makes everything in later life the blue-collar, neighborhood-driven boring,” he says. “If you could survive it, it was kind of a gift that you didn’t growing story. Nor would the young Stu have even know you were getting.” even an inkling that his genius, as it Stuart, consciously or not, was being drawn into the world of stories. He in place were, was wrapped up right there, in recognizes that his Little Village had what Southern writers often refer to as by donald g. evans that mucky water, in the prison just a storytelling culture. -

Lincoln in the Bardo

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com Lincoln in the Bardo INTRODUCTION RELATED LITERARY WORKS Lincoln in the Bardo borrows the term “Bardo” from The Bardo BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF GEORGE SAUNDERS Thodol, a Tibetan text more widely known as The Tibetan Book of . Tibetan Buddhists use the word “Bardo” to refer to George Saunders was born in 1958 in Amarillo, Texas, but he the Dead grew up in Chicago. When he was eighteen, he attended the any transitional period, including life itself, since life is simply a Colorado School of Mines, where he graduated with a transitional state that takes place after a person’s birth and geophysical engineering degree in 1981. Upon graduation, he before their death. Written in the fourteenth century, The worked as a field geophysicist in the oil-fields of Sumatra, an Bardo Thodol is supposed to guide souls through the bardo that island in Southeast Asia. Perhaps because the closest town was exists between death and either reincarnation or the only accessible by helicopter, Saunders started reading attainment of nirvana. In addition, Lincoln in the Bardo voraciously while working in the oil-fields. A eary and a half sometimes resembles Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, since later, he got sick after swimming in a feces-contaminated river, Saunders’s deceased characters deliver long monologues so he returned to the United States. During this time, he reminiscent of the self-interested speeches uttered by worked a number of hourly jobs before attending Syracuse condemned sinners in The Inferno. Taken together, these two University, where he earned his Master’s in Creative Writing. -

European Book Suggestions from Joanneke Elliott, African Studies and West European Studies Librarian, UNC-CH, with Additions from Various Sources

European Book Suggestions from Joanneke Elliott, African Studies and West European Studies Librarian, UNC-CH, with additions from various sources Albania Three Elegies for Kosovo by Ismail Kadare Summary: This slim volume tells the tale of a band of singers on the infamous Field of Blackbirds as the medieval Serbian state is defeated by the Ottoman army. Belgium Het moois dat we delen (not yet translated) by Ish Ait Hamou. Summary: Soumia and Luc live in the same neighborhood, but they don't know each other. She is desperately trying to leave the past behind. He lives in and with the past. When they get to know each other by chance, they are faced with difficult decisions. Mevrouw Verona daalt de heuvel af/Madame Verona Comes Down the Hill by Dimitri Verhulst. Summary: Years ago, Madame Verona and her husband built a home for themselves on a hill in a forest above a small village. There they lived in isolation, practicing their music, and chopping wood to see them through the cold winters. When Mr. Verona died, the locals might have expected that the legendary beauty would return to the village, but Madame Verona had enough wood to keep her warm during the years it would take to make a cello—the instrument her husband loved—and in the meantime she had her dogs for company. And then one cold February morning, when the last log has burned, Madame Verona sets off down the village path, with her cello and her memories, knowing that she will have no strength to climb the hill again.