Part One: 'Science Fiction Versus Mundane Culture', 'The Overlap Between Science Fiction and Other Genres' and 'Horror Motifs' Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teacher's Notes

Teacher’s Notes: The Maximus Black Files The Only Game in the Galaxy By Paul Collins Synopsis The Only Game in the Galaxy is the final book in the series The Maximus Black Files . The trilogy includes the previously published and very successful, Mole Hunt as well as the intriguing Dyson’s Drop. Author Paul Collins imbues his characters and settings with detailed descriptions of futuristic worlds. The story is set in a far away galaxy in a time where life on earth is a distant memory. Maximus Black is a Special Agent for RIM, an intergalactic law enforcement agency. Previously, he had set out to kill Anneke Longshadow who was his sworn enemy and also an agent at RIM. She is just as smart, just as talented, and also prepared to do just about anything to survive. Unlike Maximus however, she is loyal to RIM. She survives Max’s attempt on her life but suffers a strange type of amnesia. Whilst Max curses about her survival he is determined to ‘use’ her on a dangerous mission that should lead her to a hapless death. These main characters, Maximus Black and his nemesis, Anneke Longshadow, continue their rampant dislike of each other. However, this story also includes events where they are dependent upon each other not only for their own survival but also the protection of their family and future. They travel back in time encountering strange and dangerous virus-infected planets, grossly fierce and ugly beings, as well as attempting to solve the code that will fulfil their destiny. -

Rose Gardner Mysteries

JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. Est. 1994 RIGHTS CATALOG 2019 JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. 49 W. 45th St., 12th Floor, New York, NY 10036-4603 Phone: +1-917-388-3010 Fax: +1-917-388-2998 Joshua Bilmes, President [email protected] Adriana Funke Karen Bourne International Rights Director Foreign Rights Assistant [email protected] [email protected] Follow us on Twitter: @awfulagent @jabberworld For the latest news, reviews, and updated rights information, visit us at: www.awfulagent.com The information in this catalog is accurate as of [DATE]. Clients, titles, and availability should be confirmed. Table of Contents Table of Contents Author/Section Genre Page # Author/Section Genre Page # Tim Akers ....................... Fantasy..........................................................................22 Ellery Queen ................... Mystery.........................................................................64 Robert Asprin ................. Fantasy..........................................................................68 Brandon Sanderson ........ New York Times Bestseller.......................................51-60 Marie Brennan ............... Fantasy..........................................................................8-9 Jon Sprunk ..................... Fantasy..........................................................................36 Peter V. Brett .................. Fantasy.....................................................................16-17 Michael J. Sullivan ......... Fantasy.....................................................................26-27 -

Fictionality and the Empirical Study of Literature

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 18 (2016) Issue 2 Article 3 Fictionality and the Empirical Study of Literature Torsten Pettersson University of Uppsala Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters -

Popular Fiction: Some Theoretical Perspectives

http://www.epitomejournals.com Vol. 4, Issue 7, July 2018, ISSN: 2395-6968 POPULAR FICTION: SOME THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES Mangrule Toufik Maheboob, Ph.D. in English, Mahatma Gandhi Mahavidyalaya, Ahmedpur, Dist.-Latur (MS). ABSTRACT Popular fiction is a very significant area of literature and literary studies. At the same time it is very complicated to be defined as it is the part of ever-pervading popular culture. The field of popular fiction is a very notable part of popular culture. As popular culture is widespread and ever-pervading, popular fiction is also very vast and wide. As there is no clear boundary between the culture and popular culture, it is also very difficult to define popular fiction due to its all-pervading nature. Popular fiction is always seen and defined in contrast with literary fiction. However, many books of literary fiction share the elements of popular fiction. Similarly, many books of popular fiction include the elements of literary fiction. Hence, there is not a clear boundary between literary fiction and popular fiction. Due to this, it becomes very difficult to define the field of popular fiction and distinguish it from literary fiction. However, this difficult task of defining popular fiction can be made something easy with the help of the theory of popular fiction as proposed by some critics who have tried to define popular fiction as a special kind of cultural practice. The present study 37 Impact Factor = 3.656 Dr. Pramod Ambadasrao Pawar, Editor-in-Chief ©EIJMR All rights reserved. http://www.epitomejournals.com Vol. 4, Issue 7, July 2018, ISSN: 2395-6968 incorporates the theory of popular fiction in the light of the perspectives of some of the prominent critics, Ken Gelder, Thomas Roberts and Victor Neuburg. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

The Media Assemblage: the Twentieth-Century Novel in Dialogue with Film, Television, and New Media

THE MEDIA ASSEMBLAGE: THE TWENTIETH-CENTURY NOVEL IN DIALOGUE WITH FILM, TELEVISION, AND NEW MEDIA BY PAUL STEWART HACKMAN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Robert Markley Associate Professor Jim Hansen Associate Professor Ramona Curry ABSTRACT At several moments during the twentieth-century, novelists have been made acutely aware of the novel as a medium due to declarations of the death of the novel. Novelists, at these moments, have found it necessary to define what differentiates the novel from other media and what makes the novel a viable form of art and communication in the age of images. At the same time, writers have expanded the novel form by borrowing conventions from these newer media. I describe this process of differentiation and interaction between the novel and other media as a “media assemblage” and argue that our understanding of the development of the novel in the twentieth century is incomplete if we isolate literature from the other media forms that compete with and influence it. The concept of an assemblage describes a historical situation in which two or more autonomous fields interact and influence one another. On the one hand, an assemblage is composed of physical objects such as TV sets, film cameras, personal computers, and publishing companies, while, on the other hand, it contains enunciations about those objects such as claims about the artistic merit of television, beliefs about the typical audience of a Hollywood blockbuster, or academic discussions about canonicity. -

Introduction to First Project

THE TECHNOLOGY OF CONSENT: AMERICAN SCIENCE FICTION AND CULTURAL CRISIS IN THE 1980s A Dissertation Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Science TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada (c) Copyright by Chad Andrews 2016 Cultural Studies Ph.D. Graduate Program May 2016 ABSTRACT The Technology of Consent: American Science Fiction and Cultural Crisis in the 1980s Chad Andrews The 1980s in the United States have come into focus as years of extensive ideological and socioeconomic fracture. A conservative movement arose to counter the progressive gains of previous decades, neoliberalism became the nation’s economic mantra, and détente was jettisoned in favour of military build-up. Such developments materialized out of a multitude of conflicts, a cultural crisis of ideas, perspectives, and words competing to maintain or rework the nation’s core structures. In this dissertation I argue that alongside these conflicts, a crisis over technology and its ramifications played a crucial role as well, with the American public grasping for ways to comprehend a nascent technoculture. Borrowing from Andrew Feenberg, I define three broad categories of popular conceptualization used to comprehend a decade of mass technical and social transformations: the instrumental view, construing technology as a range of efficient tools; the substantive view, insisting technology is an environment that determines its subjects; and a critical approach, -

Science Fiction Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette English Faculty Research and Publications English, Department of 1-1-2016 Science Fiction Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. "Science Fiction," in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature, David McCooey. Oxford University Press, 2016. DOI. © 2016 Oxford University Press. Used with permission. Science Fiction Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature Science Fiction Gerry Canavan Subject: American Literature, British, Irish, Scottish, and Welsh Literatures, English Language Literatures (Other Than American and British) Online Publication Date: Mar 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.136 Summary and Keywords Science fiction (SF) emerges as a distinct literary and cultural genre out of a familiar set of world-famous texts ranging from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) to Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek (1966–) to the Marvel Cinematic Universe (2008–) that have, in aggregate, generated a colossal, communal archive of alternate worlds and possible future histories. SF’s dialectical interplay between utopian optimism and apocalyptic pessimism can be felt across the genre’s now centuries-long history, only intensifying in the 20th century as the clash between humankind’s growing technological capabilities and its ability to use those powers safely or wisely has reached existential-threat propositions, not simply for human beings but for all life on the planet. In the early 21st century, as in earlier cultural moments, the writers and critics of SF use the genre’s articulation of different societies and different possible futures as the occasion to reflect on our own present, in ways that range from full-throated defense of the status quo to the ruthless denunciation of all institutions that currently exist in the name of some other, better world. -

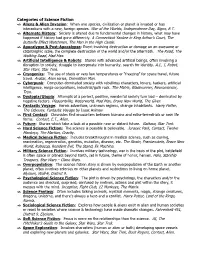

Categories of Science Fiction Aliens & Alien Invasion: When One Species, Civilization Or Planet Is Invaded Or Has Interactions with a New, Foreign Species

Categories of Science Fiction Aliens & Alien Invasion: When one species, civilization or planet is invaded or has interactions with a new, foreign species. War of the Worlds, Independence Day, Signs, E.T. Alternate History: Society is altered due to fundamental changes in history, what may have happened if history had gone differently. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, The Butterfly Effect Watchmen, The Man in the High Castle. Apocalypse & Post-Apocalypse: Event involving destruction or damage on an awesome or catastrophic scale, the complete destruction of the world and/or the aftermath. The Road, The Walking Dead, Mad Max. Artificial Intelligence & Robots: Stories with advanced artificial beings, often involving a disruption to society, struggle to incorporate into humanity, search for identity. A.I., I, Robot, Star Wars, Star Trek. Cryogenics: The use of stasis or very low temperatures or “freezing” for space travel, future travel. Avatar, Alien series, Demolition Man. Cyberpunk: Computer-dominated society with rebellious characters, loners, hackers, artificial intelligence, mega-corporations, industrial/goth rock. The Matrix, Bladerunner, Neuromancer, Tron. Dystopia/Utopia: Attempts at a perfect, positive, wonderful society turn bad – dominated by negative factors. Pleasantville, Waterworld, Mad Max, Brave New World, The Giver. Fantastic Voyage: Heroic adventure, unknown regions, strange inhabitants. Harry Potter, The Odyssey, Fantastic Voyage by Isaac Asimov First Contact: Chronicles first encounters between humans and extra-terrestrials or new life forms. Contact, E.T., Alien. Future: Stories which take a look at a possible near or distant future. Gattaca, Star Trek. Hard Science Fiction: The science is possible & believable. Jurassic Park, Contact, Twelve Monkeys, The Martian, Gravity. -

Social Science Fiction from the Sixties to the Present Instructor: Joseph Shack [email protected] Office Hours: to Be Announced

Social Science Fiction from the Sixties to the Present Instructor: Joseph Shack [email protected] Office Hours: To be announced Course Description The label “social science fiction,” initially coined by Isaac Asimov in 1953 as a broad category to describe narratives focusing on the effects of novel technologies and scientific advances on society, became a pejorative leveled at a new group of authors that rose to prominence during the sixties and seventies. These writers, who became associated with “New Wave” science fiction movement, differentiated themselves from their predecessors by consciously turning their backs on the pulpy adventure stories and tales of technological optimism of their predecessors in order to produce experimental, literary fiction. Rather than concerning themselves with “hard” science, social science fiction written by authors such as Ursula K. Le Guin and Samuel Delany focused on speculative societies (whether dystopian, alien, futuristic, etc.) and their effects on individual characters. In this junior tutorial you’ll receive a crash course in the groundbreaking science fiction of the sixties and seventies (with a few brief excursions to the eighties and nineties) through various mediums, including the experimental short stories, landmark novels, and innovative films that characterize the period. Responding to the social and political upheavals they were experiencing, each of our authors leverages particular sub-genres of science fiction to provide a pointed critique of their contemporary society. During the first eight weeks of the course, as a complement to the social science fiction we’ll be reading, students will familiarize themselves with various theoretical and critical methods that approach literature as a reflection of the social institutions from which it originates, including Marxist literary critique, queer theory, feminism, critical race theory, and postmodernism. -

Golden Fantasy: an Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing Zechariah James Morrison Seattle Pacific Nu Iversity

Seattle aP cific nivU ersity Digital Commons @ SPU Honors Projects University Scholars Spring June 3rd, 2016 Golden Fantasy: An Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing Zechariah James Morrison Seattle Pacific nU iversity Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Morrison, Zechariah James, "Golden Fantasy: An Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing" (2016). Honors Projects. 50. https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects/50 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the University Scholars at Digital Commons @ SPU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SPU. Golden Fantasy By Zechariah James Morrison Faculty Advisor, Owen Ewald Second Reader, Doug Thorpe A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University Scholars Program Seattle Pacific University 2016 2 Walk into any bookstore and you can easily find a section with the title “Fantasy” hoisted above it, and you would probably find the greater half of the books there to be full of vast rural landscapes, hackneyed elves, made-up Latinate or Greek words, and a small-town hero, (usually male) destined to stop a physically absent overlord associated with darkness, nihilism, or/and industrialization. With this predictability in mind, critics have condemned fantasy as escapist, childish, fake, and dependent upon familiar tropes. Many a great fantasy author, such as the giants Ursula K. Le Guin, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis and others, has recognized this, and either agreed or disagreed as the particulars are debated. -

Introduction to Fiction and Poetry Form, Genre, and Beyond Section Number: CRWRI-UA.815.003 Schedule: MW: 11AM - 12:15PM

Introduction to Fiction and Poetry Form, Genre, and Beyond Section number: CRWRI-UA.815.003 Schedule: MW: 11AM - 12:15PM Instructor: Charis Caputo Email: [email protected] Phone: (773) 996-4416 Texts: The Making of a Poem: The Norton Anthology of Poetic Forms, Mark Strand and Eaven Boland, eds. Autobiography of Red, Anne Carson There Are More Beautiful Things than Beyoncé, Morgan Parker American Innovations, Rivka Galchen All other reading will be distributed as handouts and/or PDFs Objective and Methods: “Genre is a minimum-security prison” --David Shields “New ideas…often emerge in the process of negotiating the charged space between what is inherited and what is known.” -- Mark Strand and Eaven Boland What is fiction, and how is it different from poetry? How is it different from nonfiction? What is a narrative? What is “realism” and how much does it differ from “genre fiction”? Can a poem be anything and can anything be a poem? Why do poetic “forms” exist, and are they outdated? Some of these might seem like obvious questions, but in fact, they’re all questions worth discussing, questions without straightforward answers. The process of becoming better writers, of exploring the possibilities of our own creativity, involves striving to discern both how and why we write, both as individuals and as participants in a culture with certain demands, assumptions, and inherited traditions. In this class, we will write, edit, and critique each other’s work, and as a necessary part of learning how to do so, we will also have readings and discussions about the craft of poetry and fiction.