Introduction to First Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teacher's Notes

Teacher’s Notes: The Maximus Black Files The Only Game in the Galaxy By Paul Collins Synopsis The Only Game in the Galaxy is the final book in the series The Maximus Black Files . The trilogy includes the previously published and very successful, Mole Hunt as well as the intriguing Dyson’s Drop. Author Paul Collins imbues his characters and settings with detailed descriptions of futuristic worlds. The story is set in a far away galaxy in a time where life on earth is a distant memory. Maximus Black is a Special Agent for RIM, an intergalactic law enforcement agency. Previously, he had set out to kill Anneke Longshadow who was his sworn enemy and also an agent at RIM. She is just as smart, just as talented, and also prepared to do just about anything to survive. Unlike Maximus however, she is loyal to RIM. She survives Max’s attempt on her life but suffers a strange type of amnesia. Whilst Max curses about her survival he is determined to ‘use’ her on a dangerous mission that should lead her to a hapless death. These main characters, Maximus Black and his nemesis, Anneke Longshadow, continue their rampant dislike of each other. However, this story also includes events where they are dependent upon each other not only for their own survival but also the protection of their family and future. They travel back in time encountering strange and dangerous virus-infected planets, grossly fierce and ugly beings, as well as attempting to solve the code that will fulfil their destiny. -

Tor.Com, Which Averages 1 Million Unique Visitors and 3 Million Pageviews Per Month, with

TORDOTCOM JULY 2021 A Psalm for the Wild-Built Becky Chambers Just when the world needs it comes a story of kindness and hope from one of the masters of Hopepunk Hugo Award-winner Becky Chambers's delightful new series gives us hope for the future. It's been centuries since the robots of Panga gained self-awareness and laid down their tools; centuries since they wandered, en masse, into the wilderness, never to be seen again; centuries since they faded into myth and urban legend. One day, the life of a tea monk is upended by the arrival of a robot, there to honor the old promise of checking in. The robot cannot go back until the question of "what do people need?" is answered. FICTION / SCIENCE FICTION / ACTION & ADVENTURE But the answer to that question depends on who you ask, and how. Tordotcom | 7/13/2021 They're going to need to ask it a lot. 9781250236210 | $20.99 / $28.99 Can. Hardcover with dust jacket | 160 pages | Carton Qty: 28 8 in H | 5 in W Becky Chambers's new series asks: in a world where people have what they Other Available Formats: want, does having more matter? Ebook ISBN: 9781250236227 Audio ISBN: 9781250807748 PRAISE "This was an optimistic vision of a lush, beautiful world that came back from the brink of disaster. Exploring it with the two main characters was a fun and MARKETING -Long-term support for Hugo Award fascinating experience.” —Martha Wells winner Becky Chambers’ Monk & Robot series, including consumer & industry mailings & advertising targeting existing "I'm the world's biggest fan of odd couple buddy road trips in science fiction, and fans & readers of hopeful science fiction this odd couple buddy road trip is a delight: funny, thoughtful, touching, sweet, and one of the most humane books I've read in a long time. -

Part One: 'Science Fiction Versus Mundane Culture', 'The Overlap Between Science Fiction and Other Genres' and 'Horror Motifs' Transcript

Part One: 'Science Fiction versus Mundane Culture', 'The overlap between Science Fiction and other genres' and 'Horror Motifs' Transcript Date: Thursday, 8 May 2008 - 11:00AM Location: Royal College of Surgeons SCIENCE FICTION VERSUS MUNDANE CULTURE Neal Stephenson When the Gresham Professors Michael Mainelli and Tim Connell did me the honour of inviting me to this Symposium, I cautioned them that I would have to attend as a sort of Idiot Savant: an idiot because I am not a scholar or even a particularly accomplished reader of SF, and a Savant because I get paid to write it. So if this were a lecture, the purpose of which is to impart erudition, I would have to decline. Instead though, it is a seminar, which feels more like a conversation, and all I suppose I need to do is to get people talking, which is almost easier for an idiot than for a Savant. I am going to come back to this Idiot Savant theme in part three of this four-part, forty minute talk, when I speak about the distinction between vegging out and geeking out, two quintessentially modern ways of spending ones time. 1. The Standard Model If you don't run with this crowd, you might assume that when I say 'SF', I am using an abbreviation of 'Science Fiction', but here, it means Speculative Fiction. The coinage is a way to cope with the problem that Science Fiction is mysteriously and inextricably joined with the seemingly unrelated literature of Fantasy. Many who are fond of one are fond of the other, to the point where they perceive them as the same thing, in spite of the fact that they seem quite different to non-fans. -

S67-00097-N210-1994-03 04.Pdf

SFRA Reriew'210, MarchI April 1994 BFRAREVIEW laauB #210. march/Aprll1BB~ II THIIIIIUE: IFlllmlnll IFFIIII: President's Message (Mead) SFRA Executive Committee Meeting Minutes (Gordon) New Members & Changes of Address "And Those Who Can't Teach.. ." (Zehner) Editorial (Mallett) IEnEIll mIICEWn!l: Forthcoming Books (BarronlMallett) News & Information (BarronlMallett) FEITUREI: Feature Article: "Animation-Reference. History. Biography" (Klossner) Feature Review: Zaki. Hoda M. Phoenix Renewed: The Survival and Mutation of Utopian ThouFdlt in North American Science Fiction, 1965- 1982. Revised Edition. (Williams) An Interview with A E. van Vogt (Mallett/Slusser) REVIEWS: Fledll: Acres. Mark. Dragonspawn. (Mallett) Card. Orson Scott. Future on Fire. (Collings) Card. Orson Scott. Xenoclde. (Brizzi) Cassutt. Michael. Dragon Season. (Herrin) Chalker. Jack L. The Run to Chaos Keep. (Runk) Chappell. Fred. More Shapes Than One. (Marx) Clarke. Arthur C. & Gentry Lee. The Garden ofRama. (Runk) Cohen. Daniel. Railway Ghosts and Highway Horrors. (Sherman) Cole. Damaris. Token ofDraqonsblood. (Becker) Constantine. Storm. Aleph. (Morgan) Constantine. Storm. Hermetech. (Morf¥in) Cooper. Louise. The Pretender. (Gardmer-Scott) Cooper. Louise. Troika. (Gardiner-Scott) Cooper. Louise. Troika. (Morgan) Dahl. Roald. The Minpins. (Spivack) Danvers. Dennis. Wilderness. (Anon.) De Haven. Tom. The End-of-Everything Man. (Anon.) Deitz. Tom. Soulsmith. (posner) Deitz. Tom. Stoneskin's Revenge. (Levy) SFRA Review 1210, MarchI Apm 1994 Denning. Troy. The Verdant Passage. (Dudley) Denton. Bradley. Buddy HoDy ~ Ahire and WeD on Ganymede. (Carper) Disch. Tom. Dark Ver.s-es & Light. (Lindow) Drake. David. The Jungle. (Stevens) Duane. Diane & Peter Morwood. Space Cops Mindblast. (Gardiner-Scon) Emshwiller. Carol. The Start ofthe End oflt AU. (Bogstad) Emshwiller. Carol. The Start ofthe End oflt AU. -

Rose Gardner Mysteries

JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. Est. 1994 RIGHTS CATALOG 2019 JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. 49 W. 45th St., 12th Floor, New York, NY 10036-4603 Phone: +1-917-388-3010 Fax: +1-917-388-2998 Joshua Bilmes, President [email protected] Adriana Funke Karen Bourne International Rights Director Foreign Rights Assistant [email protected] [email protected] Follow us on Twitter: @awfulagent @jabberworld For the latest news, reviews, and updated rights information, visit us at: www.awfulagent.com The information in this catalog is accurate as of [DATE]. Clients, titles, and availability should be confirmed. Table of Contents Table of Contents Author/Section Genre Page # Author/Section Genre Page # Tim Akers ....................... Fantasy..........................................................................22 Ellery Queen ................... Mystery.........................................................................64 Robert Asprin ................. Fantasy..........................................................................68 Brandon Sanderson ........ New York Times Bestseller.......................................51-60 Marie Brennan ............... Fantasy..........................................................................8-9 Jon Sprunk ..................... Fantasy..........................................................................36 Peter V. Brett .................. Fantasy.....................................................................16-17 Michael J. Sullivan ......... Fantasy.....................................................................26-27 -

Spring 2021 Tor.Com Catalog (PDF)

21S Macm TOR.com Page 1 of 12 A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers In A Psalm for the Wild-Built, Hugo Award-winner Becky Chambers's delightful new Monk & Robot series gives us hope for the future. It's been centuries since the robots of Earth gained self-awareness and laid down their tools; centuries since they wandered, en masse, into the wilderness, never to be seen again; centuries since they faded into myth and urban legend. One day, the life of a tea monk is upended by the arrival of a robot, there to honor the old promise of checking in. The robot cannot go back until the question of what do people need?" is answered. But the answer to that question depends on who you ask, and how. They're going to need to ask it a lot. Tor Becky Chambers's new series asks: in a world where people have what they On Sale: Jul 13/21 want, does having more matter? 5 x 8 • 160 pages " 9781250236210 • $28.50 • CL - With dust jacket Fiction / Science Fiction / Adventure This was an optimistic vision of a lush, beautiful world that came back from Series: Monk & Robot the brink of disaster. Exploring it with the two main characters was a fun and fascinating experience." - Martha Wells Notes "I'm the world's biggest fan of odd couple buddy road trips in science fiction, and this odd couple buddy road trip is a delight: funny, thoughtful, touching, Promotion sweet, and one of the most humane books I've read in a long time. -

Bill Fawcett______24951 Middle Fork Road Barrington, Illinois 60010 U.S.A

Bill Fawcett___________________________________________________ 24951 Middle Fork Road Barrington, Illinois 60010 U.S.A. 8472779686 [email protected] Bill has been a professor, teacher, corporate executive, and college dean. His entire life has been spent in the creative fields and managing other creative individuals. He is one of the founders of Mayfair Games, a board and role play gaming company. As an author Bill has written or coauthored over a dozen books and dozens of articles and short stories. As a book packager, a person who prepares series of books from concept to production for major publishers, his company Bill Fawcett & Associates has packaged over 250 titles for virtually every major publisher. He founded, and later sold, what is now the largest hobby shop in Northern Illinois. Bill’s first commercial writing appeared as articles in the Dragon Magazine and include some of the earliest appearances of classes and monster types for dungeons and Dragons. With Mayfair Games created, wrote, and edited many of the over 50 “Role Aides” Role Playing Game modules and supplements released by Mayfair in the 1970s and 1980s. During this period he also designed almost a dozen board games, including several Charles Roberts Award (Gaming's Emmy) winners such as Empire Builder and Sanctuary. Bill Fawcett continues to develop new internet projects. His novl writing began with the juvenile series, Swordquest for Ace Penguin Putnam Publishing. He wrote or cowrote four fantasy novels, beginning with the Lord of Cragsclaw. The Fleet series he created with David Drake has become a classic of military science fiction. -

SFRA Newsletter

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 8-1-1989 SFRA ewN sletter 169 Science Fiction Research Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Science Fiction Research Association, "SFRA eN wsletter 169 " (1989). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 114. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/114 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The SFRA Newsletter Publislled ten times a year for Tile Science Fiction Researcll Association by Alan Newcomer, Hypatia Press, Eugene, Oregon. Copyright @ 1989 by the SFRA. E-Mail: [email protected]. Editorial correspondence: SFRA Newsletter, Englisll Dept., Florida Atlantic U, Boca Raton, FL 33431 (Tel. 407-367-3838). Editor: Rol)ert A. Collins; Associate Editor: Catherine Fischer; Review Editor.' Rol) Latham; Film Editor: Teel Krulik; Book News Editor: Martin A. Sclllleider; Editorial Assistant: Jeanette Lawson. Send changes of address to tile Secretary, enquiries concerning subscriptions to the Treasurer, listed below. Past Presidents of SFRA Tilomas D. Clareson (1970-76) Arthur O. Lewis, Jr. (1977-78) SFRA Executive Joe De Bolt (19.79-80) James Gunn (1981-82) Committee Patricia S. Warrick (1983-84) Donalel M. Hassler (1985-86) President Past Editors of the Newsletter Elizabeth Anne Hull Fred Lerner (1971-74) Liberal Arts Division Beverly Friend (1974-78) William Rahley Harper College Roald Tweet (1978-81) Palatine, Illinois 60067 Elizabeth Anne Hull (1981-84) Richard W. -

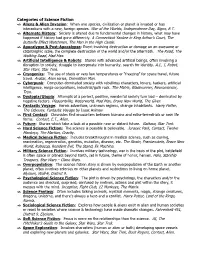

Categories of Science Fiction Aliens & Alien Invasion: When One Species, Civilization Or Planet Is Invaded Or Has Interactions with a New, Foreign Species

Categories of Science Fiction Aliens & Alien Invasion: When one species, civilization or planet is invaded or has interactions with a new, foreign species. War of the Worlds, Independence Day, Signs, E.T. Alternate History: Society is altered due to fundamental changes in history, what may have happened if history had gone differently. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, The Butterfly Effect Watchmen, The Man in the High Castle. Apocalypse & Post-Apocalypse: Event involving destruction or damage on an awesome or catastrophic scale, the complete destruction of the world and/or the aftermath. The Road, The Walking Dead, Mad Max. Artificial Intelligence & Robots: Stories with advanced artificial beings, often involving a disruption to society, struggle to incorporate into humanity, search for identity. A.I., I, Robot, Star Wars, Star Trek. Cryogenics: The use of stasis or very low temperatures or “freezing” for space travel, future travel. Avatar, Alien series, Demolition Man. Cyberpunk: Computer-dominated society with rebellious characters, loners, hackers, artificial intelligence, mega-corporations, industrial/goth rock. The Matrix, Bladerunner, Neuromancer, Tron. Dystopia/Utopia: Attempts at a perfect, positive, wonderful society turn bad – dominated by negative factors. Pleasantville, Waterworld, Mad Max, Brave New World, The Giver. Fantastic Voyage: Heroic adventure, unknown regions, strange inhabitants. Harry Potter, The Odyssey, Fantastic Voyage by Isaac Asimov First Contact: Chronicles first encounters between humans and extra-terrestrials or new life forms. Contact, E.T., Alien. Future: Stories which take a look at a possible near or distant future. Gattaca, Star Trek. Hard Science Fiction: The science is possible & believable. Jurassic Park, Contact, Twelve Monkeys, The Martian, Gravity. -

Imperial Radch Trilogy

“I Might As Well Be Human. But I’m Not.” Focalization and Narration in Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch Trilogy Roosa Töyrylä Master’s Thesis Master’s Programme in English Studies Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki May 2020 Tiedekunta – Fakultet – Faculty Koulutusohjelma – Utbildningsprogram – Degree Programme Humanistinen tiedekunta Englannin kielen ja kirjallisuuden maisteriohjelma Opintosuunta – Studieinriktning – Study Track Tekijä – Författare – Author Roosa Töyrylä Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title “I Might As Well Be Human. But I’m Not.”: Focalization and Narration in Ann Leckie’s Imperial Radch Trilogy Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu -tutkielma Toukokuu 2020 59 Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Tutkielmani käsittelee fokalisaatiota ja kerrontaa Ann Leckien Imperial Radch -trilogiassa. Trilogia on lajityypiltään tieteiskirjallisuutta ja avaruusoopperaa, ja sen päähenkilö Breq, joka toimii myös kertojana ja fokalisoijana, on ihmiskehoon istutettu tekoäly. Erityisesti keskityn tutkielmassani siihen, miten teosten muodolliset ominaisuudet liittyvät yhteen päähenkilön identiteetin kehityksen kanssa. Analyysini lähtökohtana toimii Brian McHalen huomio, että spekulatiivinen fiktio voi kirjaimellistaa narratologiassa käytettyjä käsitteitä. Lisäksi hyödynnän Monika Fludernikin luomaa kokemuksellisuuden käsitettä eli ajatusta siitä, että fiktiivisen teoksen tapahtumat eivät ainoastaan tapahdu vaan myös koetaan. Kuvaan teosten fokalisaatiota ja kerrontaa pitkälti -

Science Fiction Time Travel • Catherine Asaro • Richard K

Upcoming Releases for Summer 2021 Boundless by Jack Campbell In the 12th book of the Lost Fleet: Outlands series, the inhabitants of S’hudon wonder who their ruling Mother will assign to be in charge of Earth, while Peter tries to rescue his sister Kait and Chloe tries to revive her acting career with the help of the princeling Treble Publication Date: June 15, 2021 Girl One by Sara Flannery Murphy A dark ode to power and femininity, about a young woman whose search for her missing mother reveals the secrets of her past--including her time spent on the Homestead as one of nine babies born via parthenogenesis Publication Date: June 1, 2021 A Psalm for the Wild-Built by Becky Chambers It's been centuries since the robots of Panga gained self- awareness and laid down their tools; centuries since they wandered, en masse, into the wilderness, never to be seen again; centuries since they faded into myth and urban legend. One day, the life of a tea monk is upended by the arrival of a robot, there to honor the old promise of checking in. The robot cannot go back until the question of "what do people need?" is answered. But the answer to that question depends on who you ask, and how. Publication Date: July 13, 2021 Try These Authors: Space Operas Military • Poul Anderson • Peter F. Hamilton • Jack Campbell • Elizabeth Moon • Isaac Asimov • Frank Herbert • William Dietz • Michael Resnick • Iain Banks • Elizabeth Moon • Ian Douglas • John Ringo • Greg Bear • Larry Niven • David Drake • Fred Saberhagen • David Brin • Frederik Pohl • Joe Haldeman • Robert Sawyer • Lois McMaster Bujold • Alastair Reynolds • Robert Heinlein • Michael Stackpole • Orson Scott Card • John Scalzi • Brian Herbert • David Weber • Arthur C. -

Spring 2021 Tor Catalog (PDF)

21S Macm TOR Page 1 of 41 The Blacktongue Thief by Christopher Buehlman Set in a world of goblin wars, stag-sized battle ravens, and assassins who kill with deadly tattoos, Christopher Buehlman's The Blacktongue Thief begins a 'dazzling' (Robin Hobb) fantasy adventure unlike any other. Kinch Na Shannack owes the Takers Guild a small fortune for his education as a thief, which includes (but is not limited to) lock-picking, knife-fighting, wall-scaling, fall-breaking, lie-weaving, trap-making, plus a few small magics. His debt has driven him to lie in wait by the old forest road, planning to rob the next traveler that crosses his path. But today, Kinch Na Shannack has picked the wrong mark. Galva is a knight, a survivor of the brutal goblin wars, and handmaiden of the goddess of death. She is searching for her queen, missing since a distant northern city fell to giants. Tor On Sale: May 25/21 Unsuccessful in his robbery and lucky to escape with his life, Kinch now finds 5.38 x 8.25 • 416 pages his fate entangled with Galva's. Common enemies and uncommon dangers 9781250621191 • $34.99 • CL - With dust jacket force thief and knight on an epic journey where goblins hunger for human Fiction / Fantasy / Epic flesh, krakens hunt in dark waters, and honor is a luxury few can afford. Notes The Blacktongue Thief is fast and fun and filled with crazy magic. I can't wait to see what Christopher Buehlman does next." - Brent Weeks, New York Times bestselling author of the Lightbringer series Promotion " National print and online publicity campaign Dazzling.