25 CHAPTER 1 Breaking the Canon? Critical Reflections on “Other”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part One: 'Science Fiction Versus Mundane Culture', 'The Overlap Between Science Fiction and Other Genres' and 'Horror Motifs' Transcript

Part One: 'Science Fiction versus Mundane Culture', 'The overlap between Science Fiction and other genres' and 'Horror Motifs' Transcript Date: Thursday, 8 May 2008 - 11:00AM Location: Royal College of Surgeons SCIENCE FICTION VERSUS MUNDANE CULTURE Neal Stephenson When the Gresham Professors Michael Mainelli and Tim Connell did me the honour of inviting me to this Symposium, I cautioned them that I would have to attend as a sort of Idiot Savant: an idiot because I am not a scholar or even a particularly accomplished reader of SF, and a Savant because I get paid to write it. So if this were a lecture, the purpose of which is to impart erudition, I would have to decline. Instead though, it is a seminar, which feels more like a conversation, and all I suppose I need to do is to get people talking, which is almost easier for an idiot than for a Savant. I am going to come back to this Idiot Savant theme in part three of this four-part, forty minute talk, when I speak about the distinction between vegging out and geeking out, two quintessentially modern ways of spending ones time. 1. The Standard Model If you don't run with this crowd, you might assume that when I say 'SF', I am using an abbreviation of 'Science Fiction', but here, it means Speculative Fiction. The coinage is a way to cope with the problem that Science Fiction is mysteriously and inextricably joined with the seemingly unrelated literature of Fantasy. Many who are fond of one are fond of the other, to the point where they perceive them as the same thing, in spite of the fact that they seem quite different to non-fans. -

Fictionality and the Empirical Study of Literature

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 18 (2016) Issue 2 Article 3 Fictionality and the Empirical Study of Literature Torsten Pettersson University of Uppsala Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters -

Popular Fiction: Some Theoretical Perspectives

http://www.epitomejournals.com Vol. 4, Issue 7, July 2018, ISSN: 2395-6968 POPULAR FICTION: SOME THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES Mangrule Toufik Maheboob, Ph.D. in English, Mahatma Gandhi Mahavidyalaya, Ahmedpur, Dist.-Latur (MS). ABSTRACT Popular fiction is a very significant area of literature and literary studies. At the same time it is very complicated to be defined as it is the part of ever-pervading popular culture. The field of popular fiction is a very notable part of popular culture. As popular culture is widespread and ever-pervading, popular fiction is also very vast and wide. As there is no clear boundary between the culture and popular culture, it is also very difficult to define popular fiction due to its all-pervading nature. Popular fiction is always seen and defined in contrast with literary fiction. However, many books of literary fiction share the elements of popular fiction. Similarly, many books of popular fiction include the elements of literary fiction. Hence, there is not a clear boundary between literary fiction and popular fiction. Due to this, it becomes very difficult to define the field of popular fiction and distinguish it from literary fiction. However, this difficult task of defining popular fiction can be made something easy with the help of the theory of popular fiction as proposed by some critics who have tried to define popular fiction as a special kind of cultural practice. The present study 37 Impact Factor = 3.656 Dr. Pramod Ambadasrao Pawar, Editor-in-Chief ©EIJMR All rights reserved. http://www.epitomejournals.com Vol. 4, Issue 7, July 2018, ISSN: 2395-6968 incorporates the theory of popular fiction in the light of the perspectives of some of the prominent critics, Ken Gelder, Thomas Roberts and Victor Neuburg. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

Science Fiction Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette English Faculty Research and Publications English, Department of 1-1-2016 Science Fiction Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. "Science Fiction," in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature, David McCooey. Oxford University Press, 2016. DOI. © 2016 Oxford University Press. Used with permission. Science Fiction Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature Science Fiction Gerry Canavan Subject: American Literature, British, Irish, Scottish, and Welsh Literatures, English Language Literatures (Other Than American and British) Online Publication Date: Mar 2017 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.136 Summary and Keywords Science fiction (SF) emerges as a distinct literary and cultural genre out of a familiar set of world-famous texts ranging from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) to Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek (1966–) to the Marvel Cinematic Universe (2008–) that have, in aggregate, generated a colossal, communal archive of alternate worlds and possible future histories. SF’s dialectical interplay between utopian optimism and apocalyptic pessimism can be felt across the genre’s now centuries-long history, only intensifying in the 20th century as the clash between humankind’s growing technological capabilities and its ability to use those powers safely or wisely has reached existential-threat propositions, not simply for human beings but for all life on the planet. In the early 21st century, as in earlier cultural moments, the writers and critics of SF use the genre’s articulation of different societies and different possible futures as the occasion to reflect on our own present, in ways that range from full-throated defense of the status quo to the ruthless denunciation of all institutions that currently exist in the name of some other, better world. -

Social Science Fiction from the Sixties to the Present Instructor: Joseph Shack [email protected] Office Hours: to Be Announced

Social Science Fiction from the Sixties to the Present Instructor: Joseph Shack [email protected] Office Hours: To be announced Course Description The label “social science fiction,” initially coined by Isaac Asimov in 1953 as a broad category to describe narratives focusing on the effects of novel technologies and scientific advances on society, became a pejorative leveled at a new group of authors that rose to prominence during the sixties and seventies. These writers, who became associated with “New Wave” science fiction movement, differentiated themselves from their predecessors by consciously turning their backs on the pulpy adventure stories and tales of technological optimism of their predecessors in order to produce experimental, literary fiction. Rather than concerning themselves with “hard” science, social science fiction written by authors such as Ursula K. Le Guin and Samuel Delany focused on speculative societies (whether dystopian, alien, futuristic, etc.) and their effects on individual characters. In this junior tutorial you’ll receive a crash course in the groundbreaking science fiction of the sixties and seventies (with a few brief excursions to the eighties and nineties) through various mediums, including the experimental short stories, landmark novels, and innovative films that characterize the period. Responding to the social and political upheavals they were experiencing, each of our authors leverages particular sub-genres of science fiction to provide a pointed critique of their contemporary society. During the first eight weeks of the course, as a complement to the social science fiction we’ll be reading, students will familiarize themselves with various theoretical and critical methods that approach literature as a reflection of the social institutions from which it originates, including Marxist literary critique, queer theory, feminism, critical race theory, and postmodernism. -

Golden Fantasy: an Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing Zechariah James Morrison Seattle Pacific Nu Iversity

Seattle aP cific nivU ersity Digital Commons @ SPU Honors Projects University Scholars Spring June 3rd, 2016 Golden Fantasy: An Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing Zechariah James Morrison Seattle Pacific nU iversity Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Morrison, Zechariah James, "Golden Fantasy: An Examination of Generic & Literary Fantasy in Popular Writing" (2016). Honors Projects. 50. https://digitalcommons.spu.edu/honorsprojects/50 This Honors Project is brought to you for free and open access by the University Scholars at Digital Commons @ SPU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SPU. Golden Fantasy By Zechariah James Morrison Faculty Advisor, Owen Ewald Second Reader, Doug Thorpe A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University Scholars Program Seattle Pacific University 2016 2 Walk into any bookstore and you can easily find a section with the title “Fantasy” hoisted above it, and you would probably find the greater half of the books there to be full of vast rural landscapes, hackneyed elves, made-up Latinate or Greek words, and a small-town hero, (usually male) destined to stop a physically absent overlord associated with darkness, nihilism, or/and industrialization. With this predictability in mind, critics have condemned fantasy as escapist, childish, fake, and dependent upon familiar tropes. Many a great fantasy author, such as the giants Ursula K. Le Guin, J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis and others, has recognized this, and either agreed or disagreed as the particulars are debated. -

Literary Fiction

CLOSE-UP: LIT ERARY FICTION Glimmer Train Close-ups are single-topic, e-doc publications specifically for writers, from the editors of Glimmer Train Stories and Writers Ask. BENJAMIN PERCY, interviewed by Andrew McFadyen-Ketchum: Your stories move quickly beyond their telling and into the more complex realm of literary fiction. Peter Straub put it best when he said, “Benjamin Percy moves instinctively toward the molten center of contemporary writing, the place where genre fiction, in this case horror, overflows its boundaries and becomes something dark and grand and percipient. These stories (Refresh, Refresh) contain a brutal power and are radiant with pain—only a writer of surpassing honesty and directness could lead us here.” Yeah, that meant a lot to me, Peter’s blurb. He’s been a kind of invisible mentor—I started reading his books in middle school—so he’s been with me all along, hovering over my shoulder like a ghost, whispering in my year. And now we’re pals, which feels a little sur- real. I’m definitely following his tracks in the mud, trying to write stories that some have called “liter- ary horror,” (thinking of horror as an emotion more than a genre). Some writers, especially in the academic circuit, turn their back on genre. That snobbishness pisses Submission Calendar me off. If you look at the worst of genre fiction, CLOSE-UP: LITERARY FICTION © Glimmer Train Press • glimmertrain.org 1 sure, the characters are cardboard cut-outs, the language is transparent, but if you look at the worst of literary fiction—which has become a genre of its own—there’s plenty to complain about, too: the wankiness of the purple prose, the high boredom of the material, etc. -

Film Study Lecture on Boyz N the Hood (1991) Compiled by Jay Seller

Film Study lecture on Boyz N The Hood (1991) Compiled by Jay Seller Boys N the Hood, (1991) Directed by John Singleton, 113 Minutes Columbia Pictures Incorporated R-Rated Cast Furious Styles Larry Fishburne Doughboy Ice Cube Tre Styles Cuba Gooding, Jr. Brandi Nia Long Ricky Baker Morris Chestnut Mrs. Baker Tyra Ferrell Reva Styles Angela Bassett Tre age 10 Desi Arnez Hines, II Chris Redge Green Dooky Dedrick D. Gobert Credits Writer-Director John Singleton Editor Bruce Cannon Producer Steve Nicolaides Original Music score Stanley Clarke Director of Photography Charles Mills Casting Jaki Brown Art Direction Bruce Bellamy Awards for Boyz N the Hood 1992 Academy Awards, Nominated for Best Director, Best Writing, Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen John Singleton 1992 BMI Film and TV Awards, Stanley Clarke 1993 Image Award, Outstanding Motion Picture 1992 MTV Movie Awards, Best New Filmmaker, John Singleton 1992 MTV Movie Awards, Nominated, Best Movie 2002 National Film Preservation Board, USA, National Film Registry 1991 New York Film Critics Circle Award, Best New Director, John Singleton 1992 Political Film Society, USA, Peace Award 1992 Political Film Society, USA, Nominated for the Expose & Human Rights Award 1992 Writer Guild of America, USA, Best Screenplay Written Directly for the Screen, john Singleton 1992 Young Artist Awards, Outstanding Young Ensemble Cast in a Motion Picture Chapter 1: Start 1991 Biography for John Singleton Date of birth (location) 6 January 1968, Los Angeles, CA Birth name John Daniel Singleton Height 5' 6" Mini biography Son of mortgage broker Danny Singleton and pharmaceutical company sales executive Sheila Ward and raised in separate households by his unmarried parents, John Singleton attended the Filmic Writing Program at USC after graduating from high school in 1986. -

Literature in the 21St Century

Literature in the 21st Century: Understanding Models of Support for Literary Fiction Literature in the 21st Century: Understanding Models of Support for Literary Fiction Contents Executive Summary 3 Notes on Goals and Methodology 5 1. Data analysis 6 2. Interviews 7 3. Survey 7 4. Other research 8 Arts Council England Funding for Literature 9 Part I – The Context 10 1. The Market 10 2. Publishers, Prizes and Marketing 21 3. Ebooks and Digital Technology 29 4. Barriers to entry 33 Recap 37 Part II – Models of Support 38 1. Advances 38 2. Other Commercial Models 42 3. Grants and Not-For-Profit Support 46 4. Emerging Models of Support 48 Conclusion 52 Appendices 53 I – Limitations to the data 53 II – Interviewees and questions 53 III – About the Authors and Arts Council England 54 IV – Suggested and Further Reading 55 Trade Press 55 Journals 55 Books 58 Canelo / Arts Council England | 2 Literature in the 21st Century: Understanding Models of Support for Literary Fiction Executive Summary It’s easy to believe there was once a Golden Age for literary fiction, but the history of publishing tells us otherwise. It has rarely, if ever, been easy to support literary writing. Our current environment presents unique challenges, but also some opportunities. Changing technology, an historic shift in the markets for cultural and entertainment goods, and rapidly evolving consumer preferences all mean the assumption that literary fiction is in a precarious place must be explored in depth. This report, which was commissioned and funded by Arts Council England and prepared by Canelo, looks at the position of literary fiction today. -

Eclipsed.Pdf

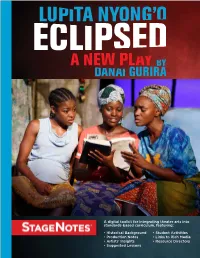

A digital toolkit for integrating theater arts into standards-based curriculum, featuring: • Historical Background • Student Activities • Production Notes • Links to Rich Media • Artists’ Insights • Resource Directory • Suggested Lessons STEPHEN C. BYRD ALIA JONES-HARVEY PAULA MARIE BLACK CAROLE SHORENSTEIN HAYS ALANI LALA ANTHONY MICHAEL MAGERS KENNY OZOUDE WILLETTE KLAUSNER DAVELLE DOMINION PICTURES EMANON PRODUCTIONS FG PRODUCTIONS THE FORSTALLS MA THEATRICALS PRESENT THE PUBLIC THEATER OSKAR EUSTIS, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR PATRICK WILLINGHAM, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR PRODUCTION OF LUPITA NYONG'O IN BY DANAI GURIRA PASCALE ARMAND AKOSUA BUSIA ZAINAB JAH SAYCON SENGBLOH JONIECE ABBOTT-PRATT AYESHA JORDAN ADEOLA ROLE SCENIC & COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN ORIGINAL MUSIC & SOUND DESIGN CLINT RAMOS JEN SCHRIEVER BROKEN CHORD CASTING FIGHT DIRECTORS VOICE & DIALECT COACH HAIR, WIG & MAKE-UP DESIGN JORDAN THALER, CSA HEIDI GRIFFITHS, CSA RICK SORDELET & BETH MCGUIRE COOKIE JORDAN LAURA SCHUTZEL, CSA CHRISTIAN KELLEY-SORDELET PRESS ADVERTISING MARKETING & SOCIAL MEDIA IN ASSOCIATION WITH ASSOCIATE PRODUCER DKC/O&M SPOTCO THE PEKOE GROUP RANDOLPH STURRUP MARVET BRITTO PRODUCTION MANAGEMENT PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER COMPANY MANAGER GENERAL MANAGER AURORA PRODUCTIONS DIANE DIVITA JENNIFER GRAVES 101 PRODUCTIONS, LTD. TECH PRODUCTION SERVICES DIRECTED BY LIESL TOMMY This production of ECLIPSED was first presented in New York on October 14, 2015 by The Public Theater. The producers wish to express their appreciation to the Theatre Development Fund for its support of this production. TABLE OF CONTENTS A timeline and short history of Liberia ... 6 Women and peacebuilding activities ............. 11 Interview with playwright and director ... 3 Historical background activities ...... 8 Resources ........................ 13 The creators ....................... 5 Cultural studies activities ............. 9 Cover photo by Joan Marcus 2 FROM THE EDITOR Eclipsed is making history. -

Menelik Shabazz • Havana, Rotterdain Filin Festivals L.A

Menelik Shabazz • Havana, RotterdaIn FilIn Festivals L.A. FilInInakers • Latin-African Cooperation $2.25 o 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 a 00000000000000 DOD 0 000 000 000 0 0 000 BL_- K LM BII IIlW o 0000000000000 000 0000000000000000000 000 0 0 Vol. 2 No.2 Published Quarterly Spring 1986 POSITIVE PRODU TIONSJ I -s BY OFFERING THREE SEPERATE OPPORTUNITIES TO SEE NEW FILMS BY AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN FI~KERSJ TAKE WORKSHOPS IN DIRECTING AND SCRIPTWRITING AND HEARING PANEL DISCUSSIONS ON AFRICAN AND AFRICAN AMERICAN FIUMMAKING EVENTS AFRlCAN·FtLM.M1NI SERIES FoURTH ANNUAL BENEFIT FILM BIOGRAPH HEATRE FESTIVAL MARCH 3-6 SLM1ER OF 1986 "BRIDGES -A RETROSPECTIVE OF AFRICAN AND AFRICAN PMERICAN CINEMA" - FALL 1986 PMER lCAN FI I..M INST IlUTE FOR MORE INFORMATION CALL 529-0220 African and African American MYPHED UHF ILM 8 1 INC. filmmakers are struggling to make their points of view known o African-American families are struggling to find media relevent to their own experiences s We are working to bring thes~ two groups togethero We distribute films nationally and internationally (members of the Committee of African Cineaste: For the Defense of African Filmmakers)o Our newest arrivals include thirteen new titles made by African film makers o For brochures contact: MYPHEDUH FILMS, INC o 48 Q Street NGE o Washington DoC. 20002 (202)529-0220 p_ln.TIlE DlSlRJCJ Of COL1JIB1I 3 BLACK FILM. REVIEW 110 SSt. NW washington, DC 20001 Editor and Publisher Contents David Nicholson Goings On Consulting Editor Independent films at the Rotterdam Festival; actors' unions meet on Tony Gittens (Black Film Insti employment issues.