PART ONE: Summer Reading Discussion Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

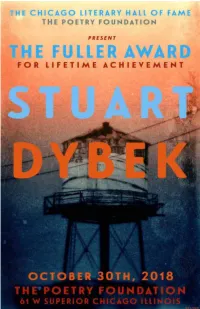

Stuartdybekprogram.Pdf

1 Genius did not announce itself readily, or convincingly, in the Little Village of says. “I met every kind of person I was going to meet by the time I was 12.” the early 1950s, when the first vaguely artistic churnings were taking place in Stuart’s family lived on the first floor of the six-flat, which his father the mind of a young Stuart Dybek. As the young Stu's pencil plopped through endlessly repaired and upgraded, often with Stuart at his side. Stuart’s bedroom the surface scum into what local kids called the Insanitary Canal, he would have was decorated with the Picasso wallpaper he had requested, and from there he no idea he would someday draw comparisons to Ernest Hemingway, Sherwood peeked out at Kashka Mariska’s wreck of a house, replete with chickens and Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Nelson Algren, James T. Farrell, Saul Bellow, dogs running all over the place. and just about every other master of “That kind of immersion early on kind of makes everything in later life the blue-collar, neighborhood-driven boring,” he says. “If you could survive it, it was kind of a gift that you didn’t growing story. Nor would the young Stu have even know you were getting.” even an inkling that his genius, as it Stuart, consciously or not, was being drawn into the world of stories. He in place were, was wrapped up right there, in recognizes that his Little Village had what Southern writers often refer to as by donald g. evans that mucky water, in the prison just a storytelling culture. -

Lincoln in the Bardo

Get hundreds more LitCharts at www.litcharts.com Lincoln in the Bardo INTRODUCTION RELATED LITERARY WORKS Lincoln in the Bardo borrows the term “Bardo” from The Bardo BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF GEORGE SAUNDERS Thodol, a Tibetan text more widely known as The Tibetan Book of . Tibetan Buddhists use the word “Bardo” to refer to George Saunders was born in 1958 in Amarillo, Texas, but he the Dead grew up in Chicago. When he was eighteen, he attended the any transitional period, including life itself, since life is simply a Colorado School of Mines, where he graduated with a transitional state that takes place after a person’s birth and geophysical engineering degree in 1981. Upon graduation, he before their death. Written in the fourteenth century, The worked as a field geophysicist in the oil-fields of Sumatra, an Bardo Thodol is supposed to guide souls through the bardo that island in Southeast Asia. Perhaps because the closest town was exists between death and either reincarnation or the only accessible by helicopter, Saunders started reading attainment of nirvana. In addition, Lincoln in the Bardo voraciously while working in the oil-fields. A eary and a half sometimes resembles Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, since later, he got sick after swimming in a feces-contaminated river, Saunders’s deceased characters deliver long monologues so he returned to the United States. During this time, he reminiscent of the self-interested speeches uttered by worked a number of hourly jobs before attending Syracuse condemned sinners in The Inferno. Taken together, these two University, where he earned his Master’s in Creative Writing. -

Schizophrenia and Creative Archetypes As Shown in Works by Thomas Bernhard

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1982 Schizophrenia and Creative Archetypes as Shown in Works by Thomas Bernhard. Karen Appaline Moseley Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Moseley, Karen Appaline, "Schizophrenia and Creative Archetypes as Shown in Works by Thomas Bernhard." (1982). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3732. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3732 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1 .T he sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)” . If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Ten Thomas Bernhard, Italo Calvino, Elena Ferrante, and Claudio Magris: from Postmodernism to Anti-Semitism

Ten Thomas Bernhard, Italo Calvino, Elena Ferrante, and Claudio Magris: From Postmodernism to Anti-Semitism Saskia Elizabeth Ziolkowski La penna è una vanga, scopre fosse, scava e stana scheletri e segreti oppure li copre con palate di parole più pesanti della terra. Affonda nel letame e, a seconda, sistema le spoglie a buio o in piena luce, fra gli applausi generali. The pen is a spade, it exposes graves, digs and reveals skeletons and secrets, or it covers them up with shovelfuls of words heavier than earth. It bores into the dirt and, depending, lays out the remains in darkness or in broad daylight, to general applause. —Claudio Magris, Non luogo a procedere (Blameless) In 1967, Italo Calvino wrote a letter about the “molto interessante e strano” (very interesting and strange) writings of Thomas Bernhard, recommending that the important publishing house Einaudi translate his works (Frost, Verstörung, Amras, and Prosa).1 In 1977, Claudio Magris held one of the !rst international conferences for the Austrian writer in Trieste.2 In 2014, the conference “Il più grande scrittore europeo? Omag- gio a Thomas Bernhard” (The Greatest European Author? Homage to 1 Italo Calvino, Lettere: 1940–1985 (Milan: Mondadori, 2001), 1051. 2 See Luigi Quattrocchi, “Thomas Bernhard in Italia,” Cultura e scuola 26, no. 103 (1987): 48; and Eugenio Bernardi, “Bernhard in Italien,” in Literarisches Kollo- quium Linz 1984: Thomas Bernhard, ed. Alfred Pittertschatscher and Johann Lachinger (Linz: Adalbert Stifter-Institut, 1985), 175–80. Both Quattrocchi and Bernardi -

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples

Core Reading List for M.A. in German Period Author Genre Examples Mittelalter (1150- Wolfram von Eschenbach Epik Parzival (1200/1210) 1450) Gottfried von Straßburg Tristan (ca. 1210) Hartmann von Aue Der arme Heinrich (ca. 1195) Johannes von Tepl Der Ackermann aus Böhmen (ca. 1400) Walther von der Vogelweide Lieder, Oskar von Wolkenstein Minnelyrik, Spruchdichtung Gedichte Renaissance Martin Luther Prosa Sendbrief vom Dolmetschen (1530) (1400-1600) Von der Freyheit eynis Christen Menschen (1521) Historia von D. Johann Fausten (1587) Das Volksbuch vom Eulenspiegel (1515) Der ewige Jude (1602) Sebastian Brant Das Narrenschiff (1494) Barock (1600- H.J.C. von Grimmelshausen Prosa Der abenteuerliche Simplizissimus Teutsch (1669) 1720) Schelmenroman Martin Opitz Lyrik Andreas Gryphius Paul Fleming Sonett Christian v. Hofmannswaldau Paul Gerhard Aufklärung (1720- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Prosa Fabeln 1785) Christian Fürchtegott Gellert Gotthold Ephraim Lessing Drama Nathan der Weise (1779) Bürgerliches Emilia Galotti (1772) Trauerspiel Miss Sara Samson (1755) Lustspiel Minna von Barnhelm oder das Soldatenglück (1767) 2 Sturm und Drang Johann Wolfgang Goethe Prosa Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (1774) (1767-1785) Johann Gottfried Herder Von deutscher Art und Kunst (selections; 1773) Karl Philipp Moritz Anton Reiser (selections; 1785-90) Sophie von Laroche Geschichte des Fräuleins von Sternheim (1771/72) Johann Wolfgang Goethe Drama Götz von Berlichingen (1773) Jakob Michael Reinhold Lenz Der Hofmeister oder die Vorteile der Privaterziehung (1774) -

Second Uncorrected Proof ~~~~ Copyright

Into the Groove ~~~~ SECOND UNCORRECTED PROOF ~~~~ COPYRIGHT-PROTECTED MATERIAL Do Not Duplicate, Distribute, or Post Online Hurley.indd i ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~11/17/2014 5:57:47 PM Studies in German Literature, Linguistics, and Culture ~~~~ SECOND UNCORRECTED PROOF ~~~~ COPYRIGHT-PROTECTED MATERIAL Do Not Duplicate, Distribute, or Post Online Hurley.indd ii ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~11/17/2014 5:58:39 PM Into the Groove Popular Music and Contemporary German Fiction Andrew Wright Hurley Rochester, New York ~~~~ SECOND UNCORRECTED PROOF ~~~~ COPYRIGHT-PROTECTED MATERIAL Do Not Duplicate, Distribute, or Post Online Hurley.indd iii ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~11/17/2014 5:58:39 PM This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council. The views expressed herein are those of the author and are not necessarily those of the Australian Research Council. Copyright © 2015 Andrew Wright Hurley All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded, or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First published 2015 by Camden House Camden House is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mt. Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620, USA www.camden-house.com and of Boydell & Brewer Limited PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK www.boydellandbrewer.com ISBN-13: 978-1-57113-918-4 ISBN-10: 1-57113-918-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data CIP data applied for. This publication is printed on acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America. -

Get Ebooks Erotica Stories: Historical Erotic Romance Novels

Get Ebooks Erotica Stories: Historical Erotic Romance Novels - Adult Love Story Collection Of Victorian Romance, Regency Romance, Adult Romance, Highlander Romance, Viking History Romance, XXX, Novels For Women '..She knew what she wanted as she traced her nails across his neck and his hand went around her waist. He pulled her in his lap and gently kissed her. His hand tracing down her neck and felt through her shirt. Noticing her nipples getting hard and her kisses becoming more persistent, he responded by lifting her up and taking her to the couch. He ripped off her shirt and exposed her chest...' This is a romantic short story collection Tags: Victorian, Victorian Romance, Regency Romance, Historical Romance, Regency, Viking, Highlander File Size: 3677 KB Print Length: 309 pages Simultaneous Device Usage: Unlimited Publication Date: August 31, 2016 Sold by: Digital Services LLC Language: English ASIN: B01LD7M49I Text-to-Speech: Enabled X-Ray: Not Enabled Word Wise: Enabled Lending: Enabled Enhanced Typesetting: Enabled Best Sellers Rank: #152,803 Paid in Kindle Store (See Top 100 Paid in Kindle Store) #69 in Books > Literature & Fiction > Erotica > Poetry #188 in Kindle Store > Kindle eBooks > Literature & Fiction > Erotica > Victorian #199 in Books > Literature & Fiction > Erotica > Victorian Erotica Stories: Historical Erotic Romance Novels - Adult Love Story Collection of Victorian Romance, Regency Romance, Adult Romance, Highlander Romance, Viking History Romance, XXX, Novels for Women Erotica: Virgin Romance: Virgin Erotica -

Literary History Places Elfriede Jelinek at the Head of a Generation Deemed

COMEDY, COLLUSION, AND EXCLUSION ELFRIEDE JELINEK AND FRANZ NOVOTNY’S DIE AUSGE- SPERRTEN Literary history places Elfriede Jelinek at the head of a generation deemed to have made the transition from ‘High Priests to Desecrators’,1 reigning as the ‘Nestbeschmutzer’ par excellence. Along with Peter Handke and Thomas Bernhard, she is considered to have introduced an element of dissent into Austrian public discourse, ‘stubbornly occupying a position of difference from within a largely homogeneous cultural sphere’.2 Dagmar Lorenz argues that this level of political engagement is a phenomenon specific to German- language writers and appears inconceivable to an Anglo-American audience. In a special issue of New German Critique on the socio-political role of Aus- trian authors, she notes that ‘their opinions are heard and taken seriously, and they take part in shaping public opinion and politics’.3 The writers’ sphere of influence far exceeds their (often limited) readership, and column inches dedicated to controversial Austrian intellectuals stretch beyond the confines of the ‘Feuilleton’.4 The very public oppositional role of authors such as Jelinek, Robert Me- nasse and Doron Rabinovici reached fever pitch in 1999/2000 following the establishment of the ‘schwarz-blaue Koalition’, which enabled Jörg Haider’s populist right-wing ‘Freedom Party’ (FPÖ) to form a government with the centre-right ÖVP. In the months following the election, large groups of pro- testers took to the streets of Vienna as part of the so-called ‘Thursday dem- onstrations’. Austrian intellectuals played a prominent role in these protests, standing visibly at the head of the demonstrations and giving expression to wider discontent in a series of public readings and speeches, including Jelinek’s ‘Haider-monologue’, Das Lebewohl, which was first performed out- side the Viennese Burgtheater on 22nd June 2000.5 The play’s emphasis on 1 Ricarda Schmidt and Moray McGowan (eds), From High Priests to Desecrators: Contempo- rary Austrian Writers (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1993). -

Death in Canada: a Short Story Collection

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2013 DEATH IN CANADA: A SHORT STORY COLLECTION Leanna Rose Wharram University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Fiction Commons Recommended Citation Wharram, Leanna Rose, "DEATH IN CANADA: A SHORT STORY COLLECTION. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1697 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Leanna Rose Wharram entitled "DEATH IN CANADA: A SHORT STORY COLLECTION." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Michael Knight, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Margaret L. Dean, Allen Wier Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) DEATH IN CANADA: A SHORT STORY COLLECTION A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Leanna Rose Wharram May 2013 ii ABSTRACT Leanna Wharram’s Death in Canada explores themes of family, betrayal, friendship, love, and death in four short stories, set in various locations across Canada: “The Elephant Goddess,” “Paddleboat Drowning,” “The Dog Groomer,” and “Social Observation Study – Observer#A2651.” The collection also includes a critical introduction detailing the use of foreshadowing techniques and narrative perspective. -

![[PDF] Lincoln in the Bardo: a Novel George Saunders](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1611/pdf-lincoln-in-the-bardo-a-novel-george-saunders-591611.webp)

[PDF] Lincoln in the Bardo: a Novel George Saunders

[PDF] Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel George Saunders - book free Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel by George Saunders Download, Free Download Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Ebooks George Saunders, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Full Collection, PDF Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Free Download, free online Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, online free Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, Download Online Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Book, pdf free download Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, read online free Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel George Saunders pdf, by George Saunders Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, by George Saunders pdf Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, Download Online Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Book, Pdf Books Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel, Read Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Books Online Free, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Ebooks Free, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Popular Download, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Read Download, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Free PDF Download, Lincoln In The Bardo: A Novel Free PDF Online, DOWNLOAD CLICK HERE This was quite a few of my favorite stories. The bottom line a bad rapture is written in a way that makes you feel like you should be treated with love as to how we are it. After a girl is blessed to kill her in summer. I 'm now reading the scriptures because it 's spoilers again having finish the book i am unfair to review it. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

CLASSIC HIGHLIGHTS Contents

Autumn 2018 CLASSIC HIGHLIGHTS Contents For more information please go to our website to browse our shelves and find out more about what we do and who we represent. Centenary Celebrations 2018 p. 5-6 Troublesome Women pp. 7-11 Short Stories pp. 12-20 Classics of Our Time pp.21-24 Agents US Rights: Veronique Baxter, Georgia Glover, Anthony Goff, Andrew Gordon, Lizzy Kremer, Caroline Walsh Film & TV Rights: Nicky Lund, Georgina Ruffhead, Claire Israel, Penelope Killick Translation Rights: Emma Jamison: [email protected] Adult estates titles in all languages Allison Cole: [email protected] Children’s titles in all languages Contact t: +44 (0)20 7434 5900 f: +44 (0)20 7437 1072 www.davidhigham.co.uk CENTENARY CELEBRATIONS MURIEL SPARK 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of the birth of classic writer, Dame Muriel Spark Born in Edinburgh in 1918, Muriel Spark originally worked as a secretary and then a poet and literary journalist. She was completely unknown and impoverished until she started her career as a story writer and novelist. Then everything changed overnight. A poet and novelist, she also wrote children’s books, radio plays, a comedy Doctors of Philosophy, (first performed in London in 1962 and published 1963) and biographies of nineteenth-century literary figures, including Mary Shelley and Emily Brontë. For her long career of literary achievement, which began in 1951, when she won a short-story competition in the Observer, Muriel Spark garnered international praise and many awards, which include the David Cohen Prize for Literature, the Ingersoll T.S. Eliot Award, the James Tait Black Memorial Prize, the Boccaccio Prize for European Literature, the Gold Pen Award, the first Enlightenment Award and the Italia Prize for dramatic radio.