Queen Regency in the Seleucid Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alexander the Great and Hephaestion

2019-3337-AJHIS-HIS 1 Alexander the Great and Hephaestion: 2 Censorship and Bisexual Erasure in Post-Macedonian 3 Society 4 5 6 Same-sex relations were common in ancient Greece and having both male and female 7 physical relationships was a cultural norm. However, Alexander the Great is almost 8 always portrayed in modern depictions as heterosexual, and the disappearance of his 9 life-partner Hephaestion is all but complete in ancient literature. Five full primary 10 source biographies of Alexander have survived from antiquity, making it possible to 11 observe the way scholars, popular writers and filmmakers from the Victorian era 12 forward have interpreted this evidence. This research borrows an approach from 13 gender studies, using the phenomenon of bisexual erasure to contribute a new 14 understanding for missing information regarding the relationship between Alexander 15 and his life-partner Hephaestion. In Greek and Macedonian society, pederasty was the 16 norm, and boys and men did not have relations with others of the same age because 17 there was almost always a financial and power difference. Hephaestion was taller and 18 more handsome than Alexander, so it might have appeared that he held the power in 19 their relationship. The hypothesis put forward here suggests that writers have erased 20 the sexual partnership between Alexander and Hephaestion because their relationship 21 did not fit the norm of acceptable pederasty as practiced in Greek and Macedonian 22 culture or was no longer socially acceptable in the Roman contexts of the ancient 23 historians. Ancient biographers may have conducted censorship to conceal any 24 implication of femininity or submissiveness in this relationship. -

Chapter 4, Section 1

Hellenistic Civilization 324 - 100 BC Philip II of Macedonia . The Macedonians were viewed as barbarians. By the 5th century BC, the Macedonians had emerged as a powerful kingdom in the north. In 359 BC, Philip II became king, and he turned Macedonia into the chief power in the Greek world. Philip II Philip II of Macedonia . The Macedonians were viewed as barbarians. By the 5th century BC, the Macedonians had emerged as a powerful kingdom in the north. In 359 BC, Philip II became king, and he turned Macedonia into the chief power in the Greek world. Philip was a great admirer of Greek culture, and he wanted to unite all of Greece under Macedonian rule. Fearing Philip, Athens allied with a number of other Greek city-states to fight the Macedonians. In 338, the Macedonians crushed the Greeks. After quickly gaining control over most of the Greek city-states, Philip turned to Sparta. He sent them a message, "You are advised to submit without further delay, for if I bring my army into your land, I will destroy your farms, slay your people, and raze your city." . Their reply was “if", both Philip and his son, Alexander, would leave the Spartans alone. By 336 BC, Philip was preparing to invade the Persian Empire when he was assassinated. The murder occurred during the celebration of his daughter’s marriage, while the king was entering the theater, he was killed by the captain his bodyguards. Alexander the Great . Alexander III was born in 356 BC. When Alexander was 13, his father Philip chose Aristotle as his tutor, and in return for teaching Alexander, Philip agreed to rebuild Aristotle's hometown which Philip had razed. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion Milns, R D Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1966; 7, 2; Proquest Pg

Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion Milns, R D Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1966; 7, 2; ProQuest pg. 159 Alexander's Seventh Phalanx Battalion R. D. Milns SOME TIME between the battle of Gaugamela and the battle of A the Hydaspes the number of battalions in the Macedonian phalanx was raised from six to seven.1 This much is clear; what is not certain is when the new formation came into being. Berve2 believes that the introduction took place at Susa in 331 B.C. He bases his belief on two facts: (a) the arrival of 6,000 Macedonian infantry and 500 Macedonian cavalry under Amyntas, son of Andromenes, when the King was either near or at Susa;3 (b) the appearance of Philotas (not the son of Parmenion) as a battalion leader shortly afterwards at the Persian Gates.4 Tarn, in his discussion of the phalanx,5 believes that the seventh battalion was not created until 328/7, when Alexander was at Bactra, the new battalion being that of Cleitus "the White".6 Berve is re jected on the grounds: (a) that Arrian (3.16.11) says that Amyntas' reinforcements were "inserted into the existing (six) battalions KC1:TCt. e8vr(; (b) that Philotas has in fact taken over the command of Perdiccas' battalion, Perdiccas having been "promoted to the Staff ... doubtless after the battle" (i.e. Gaugamela).7 The seventh battalion was formed, he believes, from reinforcements from Macedonia who reached Alexander at Nautaca.8 Now all of Tarn's arguments are open to objection; and I shall treat them in the order they are presented above. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-10444-0 — Rome and the Third Macedonian War Paul J

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-10444-0 — Rome and the Third Macedonian War Paul J. Burton Index More Information Index Abdera, Greek city on the h racian coast, 15n. second year 41 , 60 , 174 political disruption sparked by Roman h ird Macedonian War embassy, 143 second year troubles with Sparta, 13 , 82n. 23 brutalized by Hortensius, 140 Acilius Glabrio, M’. (cos. 191), 44 , 59n. 12 embassy to Rome, 140 Aetolian War s.c. de Abderitis issued, 140 , see also second year Appendix C passim given (unsolicited) strategic advice by Abrupolis, king of the h racian Sapaei, 15n. 41 Flamininus, 42 attacks Macedonia (179), 58 , 81 Syrian and Aetolian Wars Acarnania, Acarnanians, 14 second year deprived of the city of Leucas (167), 177 Battle of h ermopylae, 36 – 37 First Macedonian War recovers some cities in h essaly, 36 Roman operations in (211), 25 Aelius Ligus, P. (cos. 172), 112 politicians exiled to Italy (167), 177 Aemilius Lepidus, M. (ambassador) h ird Macedonian War embassy to Philip V at Abydus (200), 28 , second year 28n. 53 political disruption sparked by Roman Aenus and Maronea, Greek cities on the embassy, 143 h racian coast, 40 , 60 , 140 , 174 two executed by the Athenians (201), 28n. 53 declared free by the senate, 46 – 47 Achaean League, Achaeans, 12 – 13 dispute between Philip V and Rome over, Achaean War (146), 194 44 – 45 , 55 , 86 , 92 , 180 Archon- Callicrates debate (175), 61 , 61n. 29 , embassy to Rome from Maronean exiles (186/ 62n. 30 , 94 – 96 5), 45 congratulated by Rome for resisting Perseus Maronean exiles address senatorial (173), 66 , 117 commission (185), 46 conquest of the Peloponnese, 13 , 82n. -

Antiochus I Soter

Antiochus I Soter home : ancient Persia : ancient Greece : Seleucids : index : article by Jona Lendering Antiochus I Soter Antiochus I Soter ('the savior'): name of a Seleucid king, ruled from 281 to 261. Successor of: Seleucus I Nicator Relatives: Father: Seleucus I Nicator Coin of Antiochus I Soter Mother: Apame I, daughter of Spitamenes (Museum of Anatolian Wife: Stratonice I (his stepmother), daughter of Demetrius Civilizations, Ankara) Poliorcetes Children: Seleucus Laodice Apame II (married to Magas of Cyrene) Stratonice II (married to Demetrius II of Macedonia) Antiochus II Theos Main deeds: 301: Present during the Battle of Ipsus 294/293: marriage with his father's wife Stratonice I 292: made co-regent and satrap of Bactria (perhaps Seleucus was thinking of the ancient Achaemenid office of mathišta) Stay in Babylon (on several occasions?), where he showed an interest in the cults of Sin and Marduk, and in the rebuilding of the Esagila and Etemenanki September 281: death of Seleucus (more...); accession of Antiochus; Philetaerus of Pergamon buys back Seleucus' corpse 280-279: Brief war against Ptolemy II Philadelphus (First Syrian War, first part); Cappadocia becomes independent when its leader Ariarathes II and his ally Orontes III of Armenia defeat the Seleucid general Amyntas 279: Intervention in Greece: soldiers sent to Thermopylae to fight against the Galatians; they are defeated 275 Successful "Elephant Battle" against the Galatians; they enter his army as mercenaries; Antiochus is called Soter, 'victor' 274-271: Unsuccessful war against Ptolemy (First Syrian War, second part) 268: Stay in Babylonia; rebuilding of the Ezida in Borsippa 266: Execution of his son Seleucus 263: Eumenes I of Pergamon, successor of Philetaerus, declares himself independent 262: Antiochus defeated by Eumenes Page 1 Antiochus I Soter 262: Antiochus defeated by Eumenes Dies 2 June 261 Succeeded by: Antiochus II Theos Sources: During Antiochus' years as crown prince, he played a large role in Babylonian policy. -

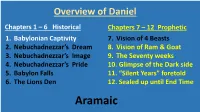

Aramaic Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8

Overview of Daniel Chapters 1 – 6 Historical Chapters 7 – 12 Prophetic 1. Babylonian Captivity 7. Vision of 4 Beasts 2. Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream 8. Vision of Ram & Goat 3. Nebuchadnezzar’s Image 9. The Seventy weeks 4. Nebuchadnezzar’s Pride 10. Glimpse of the Dark side 5. Babylon Falls 11. “Silent Years” foretold 6. The Lions Den 12. Sealed up until End Time Aramaic Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Babylon Medo- Persia Greece Rome Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Persians Medes Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 8 Greek Empire Alexander The Great Lysimachus Cassander Ptolemy Seleucus Greek Empire Chapter 8 Alexander The Great King of the South King of the North 1. Ptolemy I Soter 1. Seleucus I Nicator 2. Antiochus I Soter 2. Ptolemy II Philadelphus 3. Antiochus II Theos 3. Ptolemy III Euergetes 4. Seleucus II Callinicus 5. Seleucus III Ceraunus 4. Ptolemy IV Philopator 6. Antiochus III Great 5. Ptolemy V Epiphanes 7. Seleucus IV Philopator 6. Ptolemy VI Philometor 8. Antiochus IV Epiphanes The account in 1 Maccabees continues: “Mothers who had allowed their babies to be circumcised were put to death in accordance with the king’s decree. Their babies were hung around their necks, and their families and those who had circumcised them were put to death” (1:60, TEV). ROME 10 11 8 D.T. BEAST 10 HORNS LITTLE HORN ANTI-CHRIST 3 FELL EYES & MOUTH LARGER THAN ASSOCIATES How Long? 2300 evenings & mornings = 167 BC 164 BC Antiochus Antiochus dies sacrificed a pig on the altar Start of Temple Maccabean Rededicated / Revolt cleansed He who has an ear, let him hear what the Spirit says to the churches.‘ Rev 2:7 Rev 2:11 Rev 2:17 Rev 2:29 Rev 3:6 Rev 3:13 Rev 3:22 To Gorsley in 2011 The Lord is sharpening the focus of the church and wants you to respond: with prayer and fasting and repentance and have ears to hear what the Spirit is saying and hearts and wills to respond to His leading and directing. -

A Literary Sources

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82860-4 — The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 2nd Edition Index More Information Index A Literary sources Livy XXVI.24.7–15: 77 (a); XXIX.12.11–16: 80; XXXI.44.2–9: 11 Aeschines III.132–4: 82; XXXIII.38: 195; XXXVII.40–1: Appian, Syrian Wars 52–5, 57–8, 62–3: 203; XXXVIII.34: 87; 57 XXXIX.24.1–4: 89; XLI.20: 209 (b); ‘Aristeas to Philocrates’ I.9–11 and XLII.29–30.7: 92; XLII.51: 94; 261 V.35–40: XLV.29.3–30 and 32.1–7: 96 15 [Aristotle] Oeconomica II.2.33: I Maccabees 1.1–9: 24; 1.10–25 and 5 7 Arrian, Alexander I.17: ; II.14: ; 41–56: 217; 15.1–9: 221 8 9 III.1.5–2.2: (a); III.3–4: ; II Maccabees 3.1–3: 216 12 13 IV.10.5–12.5: ; V.28–29.1: ; Memnon, FGrH 434 F 11 §§5.7–11: 159 14 20 V1.27.3–5: ; VII.1.1–4: ; Menander, The Sicyonian lines 3–15: 104 17 18 VII.4.4–5: ; VII.8–9 and 11: Menecles of Barca FGrHist 270F9:322 26 Arrian, FGrH 156 F 1, §§1–8: (a); F 9, Pausanias I.7: 254; I.9.4: 254; I.9.5–10: 30 §§34–8: 56; I.25.3–6: 28; VII.16.7–17.1: Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae V.201b–f, 100 258 43 202f–203e: ; VI.253b–f: Plutarch, Agis 5–6.1 and 7.5–8: 69 23 Augustine, City of God 4.4: Alexander 10.6–11: 3 (a); 15: 4 (a); Demetrius of Phalerum, FGrH 228 F 39: 26.3–10: 8 (b); 68.3: cf. -

2 the Assyrian Empire, the Conquest of Israel, and the Colonization of Judah 37 I

ISRAEL AND EMPIRE ii ISRAEL AND EMPIRE A Postcolonial History of Israel and Early Judaism Leo G. Perdue and Warren Carter Edited by Coleman A. Baker LONDON • NEW DELHI • NEW YORK • SYDNEY 1 Bloomsbury T&T Clark An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Imprint previously known as T&T Clark 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com Bloomsbury, T&T Clark and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Leo G. Perdue, Warren Carter and Coleman A. Baker have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Authors of this work. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the authors. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-0-56705-409-8 PB: 978-0-56724-328-7 ePDF: 978-0-56728-051-0 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset by Forthcoming Publications (www.forthpub.com) 1 Contents Abbreviations vii Preface ix Introduction: Empires, Colonies, and Postcolonial Interpretation 1 I. -

My Frends Are Animals Study Guide

STUDY GUIDE This Study Guide includes suggestions about preparing your students for a live theatre performance in order to help them take more from the experience. Included is information and ideas on how to use the performance to enhance aspects of your education curriculum: with exercises that respond to the themes presented in the performance and the dramatic elements. Please copy and distribute this guide to your fellow teachers. BOOKING INFORMATION Please contact the Booking Coordinator for more information. Local: 604 669 0631 Toll Free: 1 866 294 7943 Email: [email protected] CONTENTS Synopsis 3 Origins of the Story 3 About Babelle Theatre 3 Themes 4 Curriculum Connections: Arts Education 4 Social Studies 5 English Language Arts 6 Activities: Pre-Performance 7 Post-Performance 8 About Axis 11 Appendix 12 Characters 12 Vocabulary 12 Pantomime 15 CREDITS » Written by James Gordon King » Directed by Marie Farsi » Dramaturgy by Chris McGregor » Production Design by Jessica Oostergo » Puppets Design by Jeny Cassady » Lighting Design by Mimi Abrahams » Sound Design by Patrick Boudreau » Production Design Assistant Megan Veaudry » Stage Management by Aidan Hammond » Performed by Caitlin McFarlane, Meaghan Chenosky, Sabrina Vellani, Tyrone Savage Babelle Theatre Company ~ Axis Theatre Company 1. SYNOPSIS An all-ages romp from the city into the wild A bear wanders from the mountains into the city and the natural boundaries are flipped! Suddenly, we’re in a dream-like world where a misfit teenager named Jo becomes a ‘wild human’ – having to outrun mobs of agitated animals and escape human conservation officers in order to find her way home. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

The Coins from the Necropolis "Metlata" Near the Village of Rupite

margarita ANDONOVA the coins from the necropolis "metlata" near the village of rupite... THE COINS FROM THE NECROPOLIS METLATA NEAR THE VILLAGE "OF RUPITE" (F. MULETAROVO), MUNICIPALITY OF PETRICH by Margarita ANDONOVA, Regional Museum of History– Blagoevgrad This article sets to describe and introduce known as Charon's fee was registered through the in scholarly debate the numismatic data findspots of the coins on the skeleton; specifically, generated during the 1985-1988 archaeological these coins were found near the head, the pelvis, excavations at one of the necropoleis situated in the left arm and the legs. In cremations in situ, the locality "Metlata" near the village of Rupite. coins were placed either inside the grave or in The necropolis belongs to the long-known urns made of stone or clay, as well as in bowls "urban settlement" situated on the southern placed next to them. It is noteworthy that out of slopes of Kozhuh hill, at the confluence of 167 graves, coins were registered only in 52, thus the Strumeshnitsa and Struma Rivers, and accounting for less than 50%. The absence of now identified with Heraclea Sintica. The coins in some graves can probably be attributed archaeological excavations were conducted by to the fact that "in Greek society, there was no Yulia Bozhinova from the Regional Museum of established dogma about the way in which the History, Blagoevgrad. souls of the dead travelled to the realm of Hades" The graves number 167 and are located (Зубарь 1982, 108). According to written sources, within an area of 750 m². Coins were found mainly Euripides, it is clear that the deceased in 52 graves, both Hellenistic and Roman, may be accompanied to the underworld not only and 10 coins originate from areas (squares) by Charon, but also by Hermes or Thanatos.