The First Century of Seleucid Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

Antiochus I Soter

Antiochus I Soter home : ancient Persia : ancient Greece : Seleucids : index : article by Jona Lendering Antiochus I Soter Antiochus I Soter ('the savior'): name of a Seleucid king, ruled from 281 to 261. Successor of: Seleucus I Nicator Relatives: Father: Seleucus I Nicator Coin of Antiochus I Soter Mother: Apame I, daughter of Spitamenes (Museum of Anatolian Wife: Stratonice I (his stepmother), daughter of Demetrius Civilizations, Ankara) Poliorcetes Children: Seleucus Laodice Apame II (married to Magas of Cyrene) Stratonice II (married to Demetrius II of Macedonia) Antiochus II Theos Main deeds: 301: Present during the Battle of Ipsus 294/293: marriage with his father's wife Stratonice I 292: made co-regent and satrap of Bactria (perhaps Seleucus was thinking of the ancient Achaemenid office of mathišta) Stay in Babylon (on several occasions?), where he showed an interest in the cults of Sin and Marduk, and in the rebuilding of the Esagila and Etemenanki September 281: death of Seleucus (more...); accession of Antiochus; Philetaerus of Pergamon buys back Seleucus' corpse 280-279: Brief war against Ptolemy II Philadelphus (First Syrian War, first part); Cappadocia becomes independent when its leader Ariarathes II and his ally Orontes III of Armenia defeat the Seleucid general Amyntas 279: Intervention in Greece: soldiers sent to Thermopylae to fight against the Galatians; they are defeated 275 Successful "Elephant Battle" against the Galatians; they enter his army as mercenaries; Antiochus is called Soter, 'victor' 274-271: Unsuccessful war against Ptolemy (First Syrian War, second part) 268: Stay in Babylonia; rebuilding of the Ezida in Borsippa 266: Execution of his son Seleucus 263: Eumenes I of Pergamon, successor of Philetaerus, declares himself independent 262: Antiochus defeated by Eumenes Page 1 Antiochus I Soter 262: Antiochus defeated by Eumenes Dies 2 June 261 Succeeded by: Antiochus II Theos Sources: During Antiochus' years as crown prince, he played a large role in Babylonian policy. -

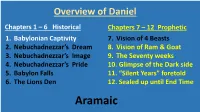

Aramaic Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8

Overview of Daniel Chapters 1 – 6 Historical Chapters 7 – 12 Prophetic 1. Babylonian Captivity 7. Vision of 4 Beasts 2. Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream 8. Vision of Ram & Goat 3. Nebuchadnezzar’s Image 9. The Seventy weeks 4. Nebuchadnezzar’s Pride 10. Glimpse of the Dark side 5. Babylon Falls 11. “Silent Years” foretold 6. The Lions Den 12. Sealed up until End Time Aramaic Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Babylon Medo- Persia Greece Rome Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Persians Medes Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 8 Greek Empire Alexander The Great Lysimachus Cassander Ptolemy Seleucus Greek Empire Chapter 8 Alexander The Great King of the South King of the North 1. Ptolemy I Soter 1. Seleucus I Nicator 2. Antiochus I Soter 2. Ptolemy II Philadelphus 3. Antiochus II Theos 3. Ptolemy III Euergetes 4. Seleucus II Callinicus 5. Seleucus III Ceraunus 4. Ptolemy IV Philopator 6. Antiochus III Great 5. Ptolemy V Epiphanes 7. Seleucus IV Philopator 6. Ptolemy VI Philometor 8. Antiochus IV Epiphanes The account in 1 Maccabees continues: “Mothers who had allowed their babies to be circumcised were put to death in accordance with the king’s decree. Their babies were hung around their necks, and their families and those who had circumcised them were put to death” (1:60, TEV). ROME 10 11 8 D.T. BEAST 10 HORNS LITTLE HORN ANTI-CHRIST 3 FELL EYES & MOUTH LARGER THAN ASSOCIATES How Long? 2300 evenings & mornings = 167 BC 164 BC Antiochus Antiochus dies sacrificed a pig on the altar Start of Temple Maccabean Rededicated / Revolt cleansed He who has an ear, let him hear what the Spirit says to the churches.‘ Rev 2:7 Rev 2:11 Rev 2:17 Rev 2:29 Rev 3:6 Rev 3:13 Rev 3:22 To Gorsley in 2011 The Lord is sharpening the focus of the church and wants you to respond: with prayer and fasting and repentance and have ears to hear what the Spirit is saying and hearts and wills to respond to His leading and directing. -

A Literary Sources

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-82860-4 — The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest 2nd Edition Index More Information Index A Literary sources Livy XXVI.24.7–15: 77 (a); XXIX.12.11–16: 80; XXXI.44.2–9: 11 Aeschines III.132–4: 82; XXXIII.38: 195; XXXVII.40–1: Appian, Syrian Wars 52–5, 57–8, 62–3: 203; XXXVIII.34: 87; 57 XXXIX.24.1–4: 89; XLI.20: 209 (b); ‘Aristeas to Philocrates’ I.9–11 and XLII.29–30.7: 92; XLII.51: 94; 261 V.35–40: XLV.29.3–30 and 32.1–7: 96 15 [Aristotle] Oeconomica II.2.33: I Maccabees 1.1–9: 24; 1.10–25 and 5 7 Arrian, Alexander I.17: ; II.14: ; 41–56: 217; 15.1–9: 221 8 9 III.1.5–2.2: (a); III.3–4: ; II Maccabees 3.1–3: 216 12 13 IV.10.5–12.5: ; V.28–29.1: ; Memnon, FGrH 434 F 11 §§5.7–11: 159 14 20 V1.27.3–5: ; VII.1.1–4: ; Menander, The Sicyonian lines 3–15: 104 17 18 VII.4.4–5: ; VII.8–9 and 11: Menecles of Barca FGrHist 270F9:322 26 Arrian, FGrH 156 F 1, §§1–8: (a); F 9, Pausanias I.7: 254; I.9.4: 254; I.9.5–10: 30 §§34–8: 56; I.25.3–6: 28; VII.16.7–17.1: Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae V.201b–f, 100 258 43 202f–203e: ; VI.253b–f: Plutarch, Agis 5–6.1 and 7.5–8: 69 23 Augustine, City of God 4.4: Alexander 10.6–11: 3 (a); 15: 4 (a); Demetrius of Phalerum, FGrH 228 F 39: 26.3–10: 8 (b); 68.3: cf. -

A Chronological Particular Timeline of Near East and Europe History

Introduction This compilation was begun merely to be a synthesized, occasional source for other writings, primarily for familiarization with European world development. Gradually, however, it was forced to come to grips with the elephantine amount of historical detail in certain classical sources. Recording the numbers of reported war deaths in previous history (many thousands, here and there!) initially was done with little contemplation but eventually, with the near‐exponential number of Humankind battles (not just major ones; inter‐tribal, dynastic, and inter‐regional), mind was caused to pause and ask itself, “Why?” Awed by the numbers killed in battles over recorded time, one falls subject to believing the very occupation in war was a naturally occurring ancient inclination, no longer possessed by ‘enlightened’ Humankind. In our synthesized histories, however, details are confined to generals, geography, battle strategies and formations, victories and defeats, with precious little revealed of the highly complicated and combined subjective forces that generate and fuel war. Two territories of human existence are involved: material and psychological. Material includes land, resources, and freedom to maintain a life to which one feels entitled. It fuels war by emotions arising from either deprivation or conditioned expectations. Psychological embraces Egalitarian and Egoistical arenas. Egalitarian is fueled by emotions arising from either a need to improve conditions or defend what it has. To that category also belongs the individual for whom revenge becomes an end in itself. Egoistical is fueled by emotions arising from material possessiveness and self‐aggrandizations. To that category also belongs the individual for whom worldly power is an end in itself. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

Greek Cities & Islands of Asia Minor

MASTER NEGATIVE NO. 93-81605- Y MICROFILMED 1 993 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES/NEW YORK / as part of the "Foundations of Western Civilization Preservation Project'' Funded by the NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES Reproductions may not be made without permission from Columbia University Library COPYRIGHT STATEMENT The copyright law of the United States - Title 17, United photocopies or States Code - concerns the making of other reproductions of copyrighted material. and Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries or other archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy the reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that for any photocopy or other reproduction is not to be "used purpose other than private study, scholarship, or for, or later uses, a research." If a user makes a request photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of fair infringement. use," that user may be liable for copyright a This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept fulfillment of the order copy order if, in its judgement, would involve violation of the copyright law. AUTHOR: VAUX, WILLIAM SANDYS WRIGHT TITLE: GREEK CITIES ISLANDS OF ASIA MINOR PLACE: LONDON DA TE: 1877 ' Master Negative # COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES PRESERVATION DEPARTMENT BIBLIOGRAPHIC MTCROFORM TAR^FT Original Material as Filmed - Existing Bibliographic Record m^m i» 884.7 !! V46 Vaux, V7aiion Sandys Wright, 1818-1885. ' Ancient history from the monuments. Greek cities I i and islands of Asia Minor, by W. S. W. Vaux... ' ,' London, Society for promoting Christian knowledce." ! 1877. 188. p. plate illus. 17 cm. ^iH2n KJ Restrictions on Use: TECHNICAL MICROFORM DATA i? FILM SIZE: 3 S'^y^/"^ REDUCTION IMAGE RATIO: J^/ PLACEMENT: lA UA) iB . -

Antiochus IV Rome

Chapter 22 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 11 & 12 Babylon Medo- 445BC 4 Persian Kings Persia Alex the Great Greece N&S Kings Antiochus IV Rome Gap of Time Time of the Gentiles 1wk 3 ½ years Opposing king. Greek Empire Chapter 8 Alexander The Great King of the South King of the North 1. Ptolemy I Soter 1. Seleucus I Nicator 2. Antiochus I Soter 2. Ptolemy II Philadelphus 3. Antiochus II Theos 3. Ptolemy III Euergetes 4. Seleucus II Callinicus 5. Seleucus III Ceraunus 4. Ptolemy IV Philopator 6. Antiochus III Great 5. Ptolemy V Epiphanes 7. Seleucus IV Philopator 6. Ptolemy VI Philometor 8. Antiochus IV Epiphanes Daniel 9:27 The 70th Week 1 Week = 7 years 3 ½ years 3 ½ years Apostasy Make a covenant Stop to Temple sacrifice with the many Stop to grain offering Abomination of Desolation Crush the elect (Jews) Jacob’s Distress Jacob’s Trouble Tribulation Daniel 11:35 Some of those who have insight will fall, in order to refine, purge and make them pure until the end time; because it is still to come at the appointed time 1 John 3:2-3 2 Beloved, now we are children of God, and it has not appeared as yet what we will be. We know that when He appears, we will be like Him, because we will see Him just as He is. 3 And everyone who has his hope fixed on Him purifies himself, just as He is pure. Zechariah 13:7-9 8 “It will come about in all the land,” Declares the LORD, “That two parts in it will be cut off and perish; But the third will be left in it. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Note : Geographical landmarks are listed under the proper name itself: for “Cape Sepias” or “Mt. Athos” see “Sepias” or “Athos.” When a people and a toponym share the same base, see under the toponym: for “Thessalians” see “Thessaly.” Romans are listed according to the nomen, i.e. C. Julius Caesar. With places or people mentioned once only, discretion has been used. Abdera 278 Aeaces II 110, 147 Abydus 222, 231 A egae 272–273 Acanthus 85, 207–208, 246 Aegina 101, 152, 157–158, 187–189, Acarnania 15, 189, 202, 204, 206, 251, 191, 200 347, 391, 393 Aegium 377, 389 Achaia 43, 54, 64 ; Peloponnesian Aegospotami 7, 220, 224, 228 Achaia, Achaian League 9–10, 12–13, Aemilius Paullus, L. 399, 404 54–56, 63, 70, 90, 250, 265, 283, 371, Aeolis 16–17, 55, 63, 145, 233 375–380, 388–390, 393, 397–399, 404, Aeschines 281, 285, 288 410 ; Phthiotic Achaia 16, 54, 279, Aeschylus 156, 163, 179 286 Aetoli Erxadieis 98–101 Achaian War 410 Aetolia, Aetolian League 12, 15, 70, Achaius 382–383, 385, 401 204, 250, 325, 329, 342, 347–348, Acilius Glabrio, M. 402 376, 378–380, 387, 390–391, 393, Acragas 119, COPYRIGHTED165, 259–261, 263, 266, 39MATERIAL6–397, 401–404 352–354, 358–359 Agariste 113, 117 Acrocorinth 377, 388–389 Agathocles (Lysimachus ’ son) 343, 345 ; Acrotatus 352, 355 (King of Sicily) 352–355, 358–359; Actium 410, 425 (King of Bactria) 413–414 Ada 297 Agelaus 391, 410 A History of Greece: 1300 to 30 BC, First Edition. Victor Parker. -

Hellenistic Central Asia: Current Research, New Directions

Hellenistic Central Asia: Current Research, New Directions Inaugural Colloquium of the Hellenistic Central Asia Research Network (HCARN) Department of Classics, University of Reading (UK) 15-17 April 2016 ABSTRACTS All conference sessions will be held in Lecture Room G 15, Henley Business School, University of Reading Whiteknights Campus. Baralay, Supratik (University of Oxford) The Arsakids between the Seleucids and the Achaemenids Abstract pending. Bordeaux, Olivier (Paris-Sorbonne) Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek numismatics: Methodologies, new research and limits Numismatics is one of the leading fields in Hellenistic Central Asia studies, since it has enabled historians to identify 45 different Graeco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kings, while written sources only speak of 10. The coins struck by the Greek kings are often remarkable, both because of their quality and the multiple innovations some of them show: Indian iconography, local language (Brahmi or Kharoshthi), new weight system, etc. Yet, broad studies by properly trained numismatists still remained scarce, while new coins mainly find their origin on the art market rather than archaeological digs. The current situation in Central Asia, especially in Afghanistan and Pakistan, does not help archaeologists to broaden their fieldwork. Die-studies are more and more often the methodology followed by the numismatists in the last decade, so as to draw as much data as possible from large corpora. During our PhD research, we focused on six kings: Diodotus I and II, Euthydemus I, Eucratides I, Menander I and Hippostratus. Beyond individual results and hypothesis, we tried to ascertain this particular methodology regarding Central Asia Greek coinages. Generally, our die-studies provided good outcomes, while most of our attempts to geographically locate mints or even borders remain quite fragile, in the lack of archaeological data. -

Chapter 8 Antiochus I, Antiochus IV And

Dodd, Rebecca (2009) Coinage and conflict: the manipulation of Seleucid political imagery. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/938/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Coinage and Conflict: The Manipulation of Seleucid Political Imagery Rebecca Dodd University of Glasgow Department of Classics Degree of PhD Table of Contents Abstract Introduction………………………………………………………………….………..…4 Chapter 1 Civic Autonomy and the Seleucid Kings: The Numismatic Evidence ………14 Chapter 2 Alexander’s Influence on Seleucid Portraiture ……………………………...49 Chapter 3 Warfare and Seleucid Coinage ………………………………………...…….57 Chapter 4 Coinages of the Seleucid Usurpers …………………………………...……..65 Chapter 5 Variation in Seleucid Portraiture: Politics, War, Usurpation, and Local Autonomy ………………………………………………………………………….……121 Chapter 6 Parthians, Apotheosis and political unrest: the beards of Seleucus II and Demetrius II ……………………………………………………………………….……131 Chapter 7 Antiochus III and Antiochus -

THE HELLENISTIC RULERS and THEIR POETS. SILENCING DANGEROUS CRITICS?* I the Beginning of the Reign of Ptolemy VII Euergetes II I

Originalveröffentlichung in: Ancient society 29.1998-99 (1998), S. 147-174 THE HELLENISTIC RULERS AND THEIR POETS. SILENCING DANGEROUS CRITICS?* i The beginning of the reign of Ptolemy VII Euergetes II in the year 145 bc following the death of his brother Ptolemy VI Philometor was described in a very negative way by ancient authors1. According to Athenaeus Ptolemy who ruled over Egypt... received from the Alexandrians appropriately the name of Malefactor. For he murdered many of the Alexandrians; not a few he sent into exile, and filled the islands and towns with men who had grown up with his brother — philologians, philosophers, mathematicians, musicians, painters, athletic trainers, physicians, and many other men of skill in their profession2. It is true that anecdotal tradition, as we find it here, is mostly of tenden tious origin, «but the course of the events suggests that the gossip-mon- * This article is the expanded version of a paper given on 2 November 1995, at the University of St Andrews, and — in a slightly changed version — on 3 November 1995, during the «Leeds Latin Seminar* on «Epigrams and Politics*. I would like to thank my colleagues there very much, especially Michael Whitby (now Warwick), for their invita tion, their hospitality, and stimulating discussions. Moreover, I would like to thank Jurgen Malitz (Eichstatt), Doris Meyer and Eckhard Wirbelauer (both Freiburg/Brsg.) for numer ous suggestions, Joachim Mathieu (Eichstatt/Atlanta) for the translation, and Roland G. Mayer (London) for his support in preparing the paper. 1 For biographical details cf. H. V olkmann , art. Ptolemaios VIII.