Alexander Hamilton & Isaac Ledyard, Pamphlet War on the Postwar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plutarch's 'Lives' and the Critical Reader

Plutarch's 'Lives' and the critical reader Book or Report Section Published Version Duff, T. (2011) Plutarch's 'Lives' and the critical reader. In: Roskam, G. and Van der Stockt, L. (eds.) Virtues for the people: aspects of Plutarch's ethics. Plutarchea Hypomnemata (4). Leuven University Press, Leuven, pp. 59-82. ISBN 9789058678584 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/24388/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: Leuven University Press All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Reprint from Virtues for the People. Aspects of Plutarchan Ethics - ISBN 978 90 5867 858 4 - Leuven University Press virtues for the people aspects of plutarchan ethics Reprint from Virtues for the People. Aspects of Plutarchan Ethics - ISBN 978 90 5867 858 4 - Leuven University Press PLUTARCHEA HYPOMNEMATA Editorial Board Jan Opsomer (K.U.Leuven) Geert Roskam (K.U.Leuven) Frances Titchener (Utah State University, Logan) Luc Van der Stockt (K.U.Leuven) Advisory Board F. Alesse (ILIESI-CNR, Roma) M. Beck (University of South Carolina, Columbia) J. Beneker (University of Wisconsin, Madison) H.-G. Ingenkamp (Universität Bonn) A.G. Nikolaidis (University of Crete, Rethymno) Chr. Pelling (Christ Church, Oxford) A. Pérez Jiménez (Universidad de Málaga) Th. -

Marathon 2,500 Years Edited by Christopher Carey & Michael Edwards

MARATHON 2,500 YEARS EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS BULLETIN OF THE INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SUPPLEMENT 124 DIRECTOR & GENERAL EDITOR: JOHN NORTH DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATIONS: RICHARD SIMPSON MARATHON – 2,500 YEARS PROCEEDINGS OF THE MARATHON CONFERENCE 2010 EDITED BY CHRISTOPHER CAREY & MICHAEL EDWARDS INSTITUTE OF CLASSICAL STUDIES SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON 2013 The cover image shows Persian warriors at Ishtar Gate, from before the fourth century BC. Pergamon Museum/Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin. Photo Mohammed Shamma (2003). Used under CC‐BY terms. All rights reserved. This PDF edition published in 2019 First published in print in 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives (CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN: 978-1-905670-81-9 (2019 PDF edition) DOI: 10.14296/1019.9781905670819 ISBN: 978-1-905670-52-9 (2013 paperback edition) ©2013 Institute of Classical Studies, University of London The right of contributors to be identified as the authors of the work published here has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Designed and typeset at the Institute of Classical Studies TABLE OF CONTENTS Introductory note 1 P. J. Rhodes The battle of Marathon and modern scholarship 3 Christopher Pelling Herodotus’ Marathon 23 Peter Krentz Marathon and the development of the exclusive hoplite phalanx 35 Andrej Petrovic The battle of Marathon in pre-Herodotean sources: on Marathon verse-inscriptions (IG I3 503/504; Seg Lvi 430) 45 V. -

The Federalist Era Lesson 1 the First President

NAME _____________________________________________ DATE __________________ CLASS ____________ The Federalist Era Lesson 1 The First President ESSENTIAL QUESTION Terms to Know precedent something done or said that becomes What are the characteristics of an example for others to follow a leader? cabinet a group of advisers to a president bond certificate that promises to repay borrowed GUIDING QUESTIONS money in the future—plus an additional amount of 1. What decisions did Washington and the new money, called interest Congress have to make about the new government? 2. How did the economy develop under the guidance of Alexander Hamilton? Where in the world? P o t o m MARYLAND a c R . WASHINGTON, D.C. White U.S. Supreme House Court U.S. Capitol VIRGINIA N c a W E m o t o S P Notes: per the screenshot of the map as placed in pages, the size of the map has been changed from 39p6 to 25p6, and labelsWhen resized todid comply it with happen? the approved styles DOPA (Discovering our Past - American History) 1780 1785 1790 1795 1800 RESG Chapter 08 George Washington 1789–1797 John Adams 1797–1801 Map Title: The Nation’s Capital File Name: C8_RESG_L2_01A_B.ai Map Size: 25p6 wide x 23p0 deep 1789 Washington 1800 Congress Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education. Permission is granted to reproduce for classroom use. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education. Permission 1795 Nation’s first chief Date/Proof: March 3, 2011 - 5th Proof 1791 Bill of Rights 2016 Font Update: February 20, 2015 becomes first justice, John Jay, retires meets in Capitol for president, Judiciary added to Constitution from Supreme Court first time Act passes You Are Here in 1798 Alien and Sedition Acts History pass, XYZ affair 113 NAME _____________________________________________ DATE __________________ CLASS ____________ The Federalist Era Lesson 1 The First President, Continued Washington Takes Office George Washington was the first president of the United States. -

The American Revolution Chapter 6 99

APTE CH R NGSSS SS.8.A.3.3 Recognize the contributions THE AMERICAN of the Founding Fathers (John Adams, Sam Adams, Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, Alexander 6 Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, James REVOLUTION Madison, George Mason, George Washington) during American Revolutionary efforts. ESSENTIAL QUESTION Why does conflict develop? The Revolutionary War was not George Washington’s first “The time is now near at hand time going into battle. During the French and Indian War, which must probably determine two horses were shot out from under him. He knew his whether Americans are to be troops would need to be brave. freemen or slaves; whether they are to have any property they can call their own…The fate of unborn millions will now depend, under God, on the courage and conduct of this army. GENERAL ORDERS,” 2 JULY 1776, IN J. C. FITZPATRICK ED. WRITINGS OF PHOTO: PHOTO: SuperStock/Getty Images GEORGE WASHINGTON VOL. 5 1932 [INSERT ART C00_000P_00000] fate of unborn millions What was Washington trying to say about the action of his men by using this phrase? In this speech, Washington was addressing the Continental Army. What do you think Copyright © by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. was the purpose of his speech? DBQ BREAKING IT DOWN George Washington chose the words of his speech carefully. Imagine that you are an American general writing to inspire troops to go into battle today. What words would you use to make your troops feel inspired? In the space, write your own speech. netw rksTM There’s More Online! The American Revolution Chapter 6 99 099_120_DOPA_WB_C06_661734.indd 99 3/30/11 3:34 PM NGSSS SS.8.A.3.3 Recognize the ON contributions of the Founding S Fathers (John Adams, Sam Adams, S E Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, L THE WAR FOR Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, George Mason, George Washington) during American INDEPENDENCE Revolutionary efforts. -

Mercenaries, Poleis, and Empires in the Fourth Century Bce

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts ALL THE KING’S GREEKS: MERCENARIES, POLEIS, AND EMPIRES IN THE FOURTH CENTURY BCE A Dissertation in History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies by Jeffrey Rop © 2013 Jeffrey Rop Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 ii The dissertation of Jeffrey Rop was reviewed and approved* by the following: Mark Munn Professor of Ancient Greek History and Greek Archaeology, Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Gary N. Knoppers Edwin Erle Sparks Professor of Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies, Religious Studies, and Jewish Studies Garrett G. Fagan Professor of Ancient History and Classics and Ancient Mediterranean Studies Kenneth Hirth Professor of Anthropology Carol Reardon George Winfree Professor of American History David Atwill Associate Professor of History and Asian Studies Graduate Program Director for the Department of History *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School iii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines Greek mercenary service in the Near East from 401- 330 BCE. Traditionally, the employment of Greek soldiers by the Persian Achaemenid Empire and the Kingdom of Egypt during this period has been understood to indicate the military weakness of these polities and the superiority of Greek hoplites over their Near Eastern counterparts. I demonstrate that the purported superiority of Greek heavy infantry has been exaggerated by Greco-Roman authors. Furthermore, close examination of Greek mercenary service reveals that the recruitment of Greek soldiers was not the purpose of Achaemenid foreign policy in Greece and the Aegean, but was instead an indication of the political subordination of prominent Greek citizens and poleis, conducted through the social institution of xenia, to Persian satraps and kings. -

Henry Knox and the Forging of Bureaucratic Autonomy

Henry Knox and the Forging of Bureaucratic Autonomy Stephen J. Rockwell As the Officer who is at the head of that [War] department is a branch of the Executive, and called to its Councils upon interesting questions of National importance[,] he ought to be a man, not only of competent skill in the science of War, but possessing a general knowledge of political subjects, of known attachment to the Government we have chosen, and of proved integrity. 1 So wrote President George Washington to Charles Cotesworth Pinckney in January 1794. Washington was expecting the resignation of his trusted former artillery commander and longtime secretary of war, Henry Knox, who had shepherded the War Department through the Confederation government, across the gap between the Confederation and government under the Constitution, and through tense negotiations and major military Secretary of War Henry Knox losses with Indian nations in the South and the Old Northwest. In writing to Pinckney, Washington emphasized how complex the job of a department head had become, just a few years into the new government. The successful department head required policy expertise, political acumen, general wisdom, networked loyalty to the government and its other officials, and personal integrity. Stephen J. Rockwell is a professor of Political Science at St. Joseph’s College, Patchogue, New York. This essay is based on a paper given at the annual conference of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic, Philadelphia, PA, July 2017. He wishes to thank Lindsay Chervinsky, Joanne Freeman, Gautham Rao, Kate Brown, Jerry Landry, and Benjamin Guterman for their questions, comments, and suggestions. -

Counterintelligence

ch5.qxd 10/18/1999 2:14 PM Page 190 Chapter 5 Counterintelligence As the shield is a practical response to the spear, so counterintelligence is to intelligence. Just as it is in the interest of a state to enhance its ability to in›uence events through the use of intelligence, it is in its interest to deny a similar ability to its opponents. The measures taken to accomplish this end fall within the nebulous boundaries of the discipline now known as counterintelligence.1 Was such a shield employed by the ancients? In general, yes— although, as with intelligence, this response must be quali‹ed in degree according to state, circumstance, and era. Assessments are, however, somewhat complicated by the use of stereotypes and propaganda by the ancients. Members of democratic states (i.e., the Athenians, who have left us a lion’s share of evidence) tended then—and still tend—to wish to conceive of their societies as open and free and of subjects of other forms of government as liable to scrutiny and censorship. In his funeral oration, Pericles declared that the Athenians “hold our city open to all and never withhold, by the use of expulsion decrees, any fact or sight that might be exposed to the sight and pro‹t of an enemy. For on the whole we trust in our own courage and readiness to the task, rather than in contrivance and deception.”2 Demosthenes similarly characterized the Athenians: “You think that freedom of speech, in every other case, ought to be shared by everyone in the polis, to such an extent that you grant it even to foreigners and slaves, and one might see many servants among us able to say whatever they wish with more freedom than citizens in some other 1. -

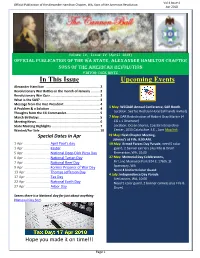

In This Issue Upcoming Events Alexander Hamilton

Vol 4 Issue 4 Official Publication of the Alexander Hamilton Chapter, WA, Sons of the American Revolution Apr 2018 Volume IV, Issue IV (April 2018) Official Publication of the WA State, Alexander Hamilton Chapter Sons of the American Revolution Editor: dick motz In This Issue Upcoming Events Alexander Hamilton ....................................................... 2 Revolutionary War Battles in the month of January ......... 2 Revolutionary War Quiz .................................................. 2 What is the SAR? ............................................................. 3 Message from the Vice President ..................................... 4 A Problem & a Solution ................................................... 4 5 May: WSSDAR Annual Conference, SAR Booth. Thoughts from the CG Commander .................................. 5 Location: SeaTac Red Lion Hotel (all hands invited) March Birthdays .............................................................. 5 7 May: DAR Rededication of Robert Gray Marker (4 Meeting News ................................................................. 6 CG + 1 Drummer) State Meeting Highlights ................................................. 7 Location: Ocean Shores, Coastal Interpretive Wanted/For Sale ............................................................. 10 Center, 1033 Catala Ave. S.E., 1pm Map link Special Dates in Apr 19 May: Next Chapter Meeting, Johnny’s at Fife, 9:00 AM. 1 Apr ........................... April Fool’s day 19 May: Armed Forces Day Parade, need 5 color 1 Apr .......................... -

Poetica, Retorica E Comunicazione Nella Tradizione Classica ADOLF M

LEXIS Poetica, retorica e comunicazione nella tradizione classica 33.2015 ADOLF M. HAKKERT EDITORE Direzione VITTORIO CITTI PAOLO MASTANDREA ENRICO MEDDA Redazione STEFANO AMENDOLA, GUIDO AVEZZÙ, FEDERICO BOSCHETTI, CLAUDIA CASALI, LIA DE FINIS, CARLO FRANCO, ALESSANDRO FRANZOI, MASSIMO MANCA, STEFANO MASO, LUCA MONDIN, GABRIELLA MORETTI, MARIA ANTONIETTA NENCINI, PIETRO NOVELLI, STEFANO NOVELLI, GIOVANNA PACE, ANTONIO PISTELLATO, RENATA RACCANELLI, GIOVANNI RAVENNA, ANDREA RODIGHIERO, GIANCARLO SCARPA, PAOLO SCATTOLIN, LINDA SPINAZZÈ, MATTEO TAUFER Comitato scientifico MARIA GRAZIA BONANNO, ANGELO CASANOVA, ALBERTO CAVARZERE, GENNARO D’IPPOLITO, LOWELL EDMUNDS, PAOLO FEDELI, ENRICO FLORES, PAOLO GATTI, MAURIZIO GIANGIULIO, GIAN FRANCO GIANOTTI, PIERRE JUDET DE LA COMBE, MARIE MADELEINE MACTOUX, GIUSEPPE MASTROMARCO, GIANCARLO MAZZOLI, GIAN FRANCO NIEDDU, CARLO ODO PAVESE, WOLFGANG RÖSLER, PAOLO VALESIO, MARIO VEGETTI, PAOLA VOLPE CACCIATORE, BERNHARD ZIMMERMANN LEXIS – Poetica, retorica e comunicazione nella tradizione classica http://www.lexisonline.eu/ [email protected], [email protected] Direzione e Redazione: Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici Palazzo Malcanton Marcorà – Dorsoduro 3484/D I-30123 Venezia Vittorio Citti [email protected] Paolo Mastandrea [email protected] Enrico Medda [email protected] Pubblicato con il contributo di: Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici (Università degli Studi di Salerno) Copyright by Vittorio Citti ISSN 2210-8823 ISBN 978-90-256-1300-6 Lexis, in accordo ai principi internazionali di trasparenza in sede di pubblicazioni di carattere scientifico, sottopone tutti i testi che giungono in redazione a un processo di doppia lettura anonima (double-blind peer review, ovvero refereeing) affidato a specialisti di Università o altri Enti italiani ed esteri. -

Lesson Title: Hamilton's

Lesson Title: Hamilton’s War Grade Levels : 9-12 Time Allotment: Three 45-minute class periods Overview: This high school lesson plan uses video clips from REDISCOVERING ALEXANDER HAMILTON and a website featuring interactive animations of Revolutionary War battles to explore Alexander Hamilton’s military career in three different engagements: The Battle for New York The Battle of Princeton, and the Siege of Yorktown. The Introductory Activity dispels the common misconception that the Revolution was primarily fought by “minutemen” militiamen using guerilla tactics against the British, and establishes the primary role of the Continental Army in the American war effort. The Learning Activities uses student organizers to focus students’ online exploration of the battles of New York, Princeton, and Yorktown, focusing on Alexander Hamilton’s role. The Culminating Activity challenges students to create their own organizer for a different Revolutionary War battle. This lesson is best used during a unit on the American Revolution, after the key causes for the conflict have been established. Subject Matter: History Learning Objectives: Students will be able to: • Distinguish between “irregular” and “regular” military forces in the 18 th century and outline their relative merits • Explain the context and consequences for the battles of New York, Princeton, and Yorktown • Describe the general course of events in each of these actions, noting key turning points • Discuss how historical fact can sometimes be distorted or embellished for effect • Outline -

Lessons from the Musical “Hamilton” Shanedra Nowell, Oklahoma

The Ten-Dollar Founding Father & The American Revolution: Lessons from the musical “Hamilton” Shanedra Nowell, Oklahoma State University ([email protected]) & Lauren Reddout, Edmond Sequoyah Middle School ([email protected]) Resources Websites: https://oeta.pbslearningmedia.org/collection/hamiltons-america/#.WcKUqciGPIU http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/episodes/hamiltons-america/ https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-by-era/hamilton http://www.slj.com/2016/05/resources/teaching-with-hamilton/#_ http://www.newsweek.com/2016/02/19/hamilton-biggest-thing-broadway-being-taug ht-classrooms-all-over-424212.html http://larryferlazzo.edublogs.org/2016/02/15/the-best-teachinglearning-resources-on-t he-musical-hamilton/ http://www.mountvernon.org/education/educational-resources-and-hamilton/ (sources for each song) https://learning.blogs.nytimes.com/2016/03/24/the-ten-dollar-founding-father-witho ut-a-father-teaching-and-learning-with-hamilton/?mcubz=0 (primary sources also paired with songs) https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/08/04/education/edlife/high-school-hami lton-quiz.html?mcubz=0 https://www.loc.gov/rr/program/bib/hamilton/memory.html (Library of Congress Alexander Hamilton collection of primary sources) Yorktown- Nathional Park Service https://www.nps.gov/york/index.htm & https://www.nps.gov/york/learn/historyculture/hamiltonbio.htm Videos: Top 10 Best Hamilton Songs: https://youtu.be/bhwv5-tFUJM The Rap on 'Hamilton': American History Meets Hip Hop: https://youtu.be/zh8rIcRoMp8 Rapping, deconstructed: -

ATINER's Conference Paper Proceedings Series LIT2017-0021

ATINER CONFERENCE PRESENTATION SERIES No: LIT2017-0021 ATINER’s Conference Paper Proceedings Series LIT2017-0021 Athens, 22 August 2017 Themistocles' Hetairai in a Fragment of Idomeneus of Lampsacus: A Small Commentary Marina Pelluci Duarte Mortoza Athens Institute for Education and Research 8 Valaoritou Street, Kolonaki, 10683 Athens, Greece ATINER’s conference paper proceedings series are circulated to promote dialogue among academic scholars. All papers of this series have been blind reviewed and accepted for presentation at one of ATINER’s annual conferences according to its acceptance policies (http://www.atiner.gr/acceptance). © All rights reserved by authors. 1 ATINER CONFERENCE PRESENTATION SERIES No: LIT2017-0021 ATINER’s Conference Paper Proceedings Series LIT2017-0021 Athens, 24 August 2017 ISSN: 2529-167X Marina Pelluci Duarte Mortoza, Independent Researcher, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil Themistocles' Hetairai in a Fragment of Idomeneus of Lampsacus: A Small Commentary1 ABSTRACT This paper aims to be a small commentary on a fragment cited by Athenaeus of Naucratis (2nd-3rd AD) in his Deipnosophistai. This is his only surviving work, which was composed in 15 books, and verses on many different subjects. It is an enormous amount of information of all kinds, mostly linked to dining, but also on music, dance, games, and all sorts of activities. On Book 13, Athenaeus puts the guests of the banquet talking about erotic matters, and one of them cites this fragment in which Idomeneus of Lampsacus (ca. 325-270 BCE) talks about the entrance of the great Themistocles in the Agora of Athens: in a car full of hetairai. Not much is known about Idomeneus, only that he wrote books on historical and philosophical matters, and that nothing he wrote survived.