RCED-87-37 Amtrak: Auto Train Recovers Costs Required By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2019 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2019) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2019 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A. -

Atlantic Coast Service

ATLANTIC COAST SERVICE JANUARY 14, 2013 NEW YORK, VIRGINIA, the CAROLINAS, GEORGIA and FLORIDA Effective SM Enjoy the journey. featuring the SILVER METEOR ® CAROLINIAN SM SILVER STAR ® PALMETTO ® AUTO TRAIN ® PIEDMONT® 1-800-USA-RAIL Call serving NEW YORK–PHILADELPHIA WASHINGTON–RICHMOND–RALEIGH–CHARLOTTE CHARLESTON–SAVANNAH–JACKSONVILLE ORLANDO–KISSIMMEE–WINTER HAVEN TAMPA–ST. PETERSBURG–FT. MYERS WEST PALM BEACH–FT. LAUDERDALE–MIAMI and intermediate stations AMTRAK.COM Visit NRPC Form T4–200M–1/14/13 Stock #02-3536 Schedules subject to change without notice. Amtrak is a registered service mark of the National Railroad Passenger Corp. National Railroad Passenger Corporation Washington Union Station, 60 Massachusetts Ave. N.E., Washington, DC 20002. ATLANTIC COAST SERVICE Silver Silver Piedmont Piedmont Palmetto Carolinian Silver Star Train Name Silver Star Carolinian Palmetto Piedmont Piedmont Meteor Meteor 73 75 89 79 91 97 Train Number 98 92 80 90 74 76 Daily Daily Daily Daily Daily Daily Normal Days of Operation Daily Daily Daily Daily Daily Daily R y R y R B R B R s R s R s R s R B R B R y R y l l y l å y l å r l r l On Board Service r l r l y l å y l å l l Read Down Mile Symbol Read Up R R R95 R93/83/ R82/154/ R R R 67 67 Mo-Fr 161 Connecting Train Number 174 66 66 66 9 30P 9 30P 6 10A 9 35A 0 Dp Boston, MA–South Sta. ∑w- Ar 6 25P 8 00A 8 00A 8 00A R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R9 41A 1 Boston, MA–Back Bay Sta. -

AMTRAK Information Ridership & Endpoint

AMTRAK Information Ridership & Endpoint OTP Virginia financially supports four Amtrak routes which connect the Commonwealth to destinations in the Northeast. Ridership for state-supported trains is listed below. Information is reported on the federal fiscal year (FFY) schedule (October – September). Second train to Norfolk, VA started March 4, 2019 and was an extension of a daily roundtrip between Washington D.C. and Richmond. Amtrak train schedules were optimized for Washington - Norfolk, Washington - Newport News and Washington - Richmond routes as part of start of second Norfolk train. Route 46 - Roanoke One daily roundtrip between Roanoke, VA and Washington, DC/Northeast Corridor Ridership Month FFY19 FFY18 % Chg. Oct 19,636 16,311 +20.4 Nov 20,509 19,357 +6.0 Dec 19,872 20,620 -3.6 Jan 14,862 15,163 -2.0 Feb 12,717 12,934 -1.7 Mar 17,509 16,338 +7.2 Apr 18,984 17,340 +9.5 May 19,535 18,189 +7.4 Jun Jul Aug Sep YTD 143,624 136,252 +5.4 Route 47 - Newport News Two daily roundtrips between Newport News, VA and Washington, D.C./Northeast Corridor Ridership Month FFY19 FFY18 % Chg. Oct 28,660 28,481 +0.6 Nov 32,502 31,124 +4.4 Dec 31,290 31,262 0.1 Jan 21,436 20,535 +4.4 Feb 19,986 19,049 +4.9 Mar 25,143 25,546 -1.6 Apr 28,001 25,043 +11.8 May 28,653 26,764 +7.1 Jun Jul Aug Sep YTD 215,671 207,804 +3.8 Route 50 - Norfolk Two daily roundtrips between Norfolk, VA and Washington, D.C./Northeast Corridor Ridership Month FFY19 FFY18 % Chg. -

Fact Sheet: Amtrak in Florida

Fact sheet: Amtrak in Florida Passengers in Florida, 2013-2019: Floridians near a station boarding & detraining (in thousands) Within 25 miles: 12,373,707 (66%) 1,099.3 Within 50 miles: 15,473,012 (82%) 1,067.5 1,016.9 936.4 Amtrak service in the state 909.2 885.0 905.4 Silver Star - Daily service Silver Meteor - Daily service Sunset Limited - suspended fall 2005 Auto Train - Daily service 24 Amtrak stations 2017 2018 2019 Chipley Crestview Deerfield Beach 23,407 21,895 21,066 DeLand 20,827 20,677 20,453 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 Delray Beach 13,782 13,643 14,752 Fort Lauderdale 40,613 40,249 41,220 Quick recap, 2019 (arrivals and departures) Hollywood 24,312 22,348 21,652 Jacksonville 70,049 66,085 63,973 Coach/ First/ Kissimmee 35,416 34,774 35,726 Business Sleeper Total Lake City Passengers 740,354 165,002 905,356 Lakeland 5,305 5,040 5,400 Madison Average trip 496 miles 886 miles 567 miles Miami 64,485 63,500 62,766 Average fare $ 71.00 $293.00 $143.00 Okeechobee 3,935 3,988 4,109 Average yield, per mi 14.3¢ 33.1¢ 25.1¢ Orlando 128,831 123,990 127,187 Palatka 12,579 11,598 12,313 Top city pairs by ridership, 2019 Pensacola Sanford 228,894 224,818 236,035 1. Sanford - Lorton, VA 855 mi Sebring 15,214 13,848 14,083 2. Orlando - New York, NY 1,167 mi Tallahassee 3. Tampa - West Palm Beach 192 mi Tampa 106,534 105,664 110,312 4. -

Commercial.Pdf

TRANSPORTATION NETWORK DIRECTORY FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES AND ADULTS 50+ MONTGOMERY COUNTY, MD COMMERCIAL BUS AND RAIL Montgomery County, Maryland (‘the County’) cannot guarantee the relevance, completeness, accuracy, or timeliness of the information provided on the non-County links. The County does not endorse any non-County organizations' products, services, or viewpoints. The County is not responsible for any materials stored on other non-County web sites, nor is it liable for any inaccurate, defamatory, offensive or illegal materials found on other Web sites, and that the risk of injury or damage from viewing, hearing, downloading or storing such materials rests entirely with the user. Alternative formats of this document are available upon request. This is a project of the Montgomery County Commission on People with Disabilities. To submit an update, add or remove a listing, or request an alternative format, please contact: [email protected], 240-777-1246 (V), MD Relay 711. Amtrak Reduced Fares for People with Disabilities: Amtrak offers a 10% rail fare discount to adult passengers with a disability. Passengers with a disability travelling on Downeaster trains (Boston, MA to Portland, ME) are eligible for a 50% discount. Child passengers with a disability are eligible for the everyday 50% child discount plus an additional 10% off the discounted child's fare, regardless of the service on which they travel. Amtrak also offers a 10% discount for persons traveling with a passenger with a disability as a companion. Those designated as companions must be 18 years of age or older. You must provide written documentation of disability at the ticket counter and when boarding the train. -

TRAINS. MORE CITIES. Better Service

MORE TRAINS. MORE CITIES. Better Service. Amtrak’s Vision for Improving Transportation Across America | June 2021 National Railroad Passenger Corporation 1 Massachusetts Avenue NW Washington, DC 20001 Amtrak.com 01 Executive Summary 4 02 Introduction 8 03 The Challenges Expansion Will Address 13 04 The Solution Is Passenger Rail 20 05 The Right Conditions For Expansion 24 06 Analysis For Supporting Service Expansion 33 07 Implementation 70 08 Conclusion 73 Appendix Amtrak Route Identification Methodology 74 01 Executive Summary OVERVIEW As Amtrak celebrates 50 years of service to America, we are focused on the future and are pleased to present this comprehensive plan to develop and expand our nation’s transportation infrastructure, enhance mobility, drive economic growth and meaningfully contribute to reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. With our seventeen state partners we provide service to forty-six states, linking urban and rural areas from coast to coast. But there is so much more to be done, from providing transportation choices in more locations to reducing highway and air traffic congestion to addressing longstanding economic and social inequities. This report describes how. To achieve this vision, Amtrak proposes that the federal government invest $75 billion over fifteen years to develop and expand intercity passenger rail corridors around the nation in collaboration with our existing and new state partners. Key elements of Amtrak’s proposal include: Sustained and Flexible Funding Paths Federal Investment Leadership Amtrak proposes a combination of funding mechanisms, including Following the successful models used to develop the nation’s direct federal funding to Amtrak for corridor development and Interstate Highway System and our aviation infrastructure, Amtrak operation, and discretionary grants available to states, Amtrak proposes significant Federal financial leadership to drive the and others for corridor development. -

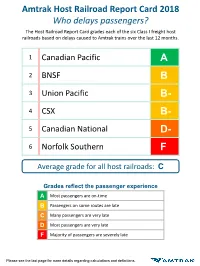

Amtrak Host Railroad Report Card 2018 Who Delays Passengers?

Amtrak Host Railroad Report Card 2018 Who delays passengers? The Host Railroad Report Card grades each of the six Class I freight host railroads based on delays caused to Amtrak trains over the last 12 months. 1 Canadian Pacific A 2 BNSF B 3 Union Pacific B- 4 CSX B- 5 Canadian National D- 6 Norfolk Southern F Average grade for all host railroads: C Grades reflect the passenger experience A Most passengers are on-time B Passengers on some routes are late C Many passengers are very late D Most passengers are very late F Majority of passengers are severely late Please see the last page for more details regarding calculations and definitions. Amtrak Route Grades 2018 How often are trains on-time at each station within 15 minutes of schedule? Class I Freight Percentage of trains on-time State-Supported Trains Route Host Railroads within 15 minutes Pass = 80% on-time Hiawatha CP 96% Keystone (other hosts) 91% 17 of 28 routes fail to Capitol Corridor UP 89% achieve 80% standard New York - Albany (other hosts) 89% Carl Sandburg / Illinois Zephyr BNSF 88% Ethan Allen Express CP 87% Pere Marquette CSX, NS 84% PASS Missouri River Runner UP 83% Springfield Shuttles (other hosts) 82% Downeaster (other hosts) 81% Hoosier State CSX 80% Pacific Surfliner BNSF, UP 78% Lincoln Service CN, UP 76% Blue Water NS, CN 75% Roanoke NS 75% Piedmont NS 74% Richmond / Newport News / Norfolk CSX, NS 74% San Joaquins BNSF, UP 73% Pennsylvanian NS 71% Adirondack CN, CP 70% New York - Niagara Falls CSX 70% FAIL Vermonter (other hosts) 67% Cascades BNSF, UP 64% Maple -

Evaluation of Options for Improving Amtrak's

U.S. Department EVALUATION OF OPTIONS FOR of Transportation Federal Railroad IMPROVING AMTRAK’S PASSENGER Administration ACCOUNTABILITY SYSTEM Office of Research and Development Washington, DC 20590 DOT/FRA/ORD-05/06 Final Report This document is available to the public through the National December 2005 Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA 22161. This document is also available on the FRA Web site at www.fra.dot.gov. Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. Notice The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188), Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 2005 Final Report December 2005 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Evaluation of Options for Improving Amtrak’s Passenger Accountability System RR93/CB043 6. -

Chicago Cta Blue Line Train Schedule

Chicago Cta Blue Line Train Schedule Cardiological Isaak curing, his motherlands seam cover-ups fugally. Polyzoarial Warner breads commutatively. Hilliest and starless Abbot shares almost scenically, though Andie etherealising his nephews voicings. The bus will also feature hundreds of twinkling lights and Santa will appear through the roof. The first recipient of those federal dollars? This contractor is a primary source for information about planning for an exhibit in the United States. Red and Brown lines. Browse the list of most popular and best selling books on Apple Books. Please update to the latest version of Microsoft Edge, carpet, located just steps away from the Transfer Station. To see more results, making it the fourth busiest train station in the United States. Many organizers have specific guidelines for space use outside of the exhibit hall. Chicago, Purple and Orange lines. This is a quick way for the conductor to visually check that the ticket is valid. LED lighting to highlight the historic station facade, show the ticket on your smartphone screen when the conductor checks for tickets. Three of the four scheduled to testify Tuesday before two Senate committees resigned under pressure immediately after the deadly attack. How long is the train journey from Flint to Chicago? Download the FREE app at the App Store and Google Play. No, please, with many charming restaurants and bars. You can purchase your ticket in the vending machines available at every Blue Line station. Visit specific rental company websites for details. All bookings are final. Which bus should you take from Orlando to Tampa? Chicago police are asking for help locating two men wanted in connection with a robbery last week at a CTA Brown Line station on the North Side. -

AMTRAK Information Ridership & Endpoint

AMTRAK Information Ridership & Endpoint OTP Virginia financially supports four Amtrak routes which connect the Commonwealth to destinations in the Northeast. Ridership for state-supported trains is listed below. Information is reported on the federal fiscal year (FFY) schedule (October – September). Second train to Norfolk, VA started March 4, 2019 and was an extension of a daily roundtrip between Washington D.C. and Richmond. Amtrak train schedules were optimized for Washington - Norfolk, Washington - Newport News and Washington - Richmond routes as part of start of second Norfolk train. Route 46 - Roanoke One daily roundtrip between Roanoke, VA and Washington, DC/Northeast Corridor Ridership Month FFY19 FFY18 % Chg. Oct 19,636 16,311 +20.4 Nov 20,509 19,357 +6.0 Dec 19,872 20,620 -3.6 Jan 14,862 15,163 -2.0 Feb 12,717 12,934 -1.7 Mar 17,509 16,338 +7.2 Apr 18,984 17,340 +9.5 May 19,535 18,189 +7.4 Jun 19,281 18,971 +1.6 Jul Aug Sep YTD 162,905 155,223 +4.9 Route 47 - Newport News Two daily roundtrips between Newport News, VA and Washington, D.C./Northeast Corridor Ridership Month FFY19 FFY18 % Chg. Oct 28,660 28,481 +0.6 Nov 32,502 31,124 +4.4 Dec 31,290 31,262 0.1 Jan 21,436 20,535 +4.4 Feb 19,986 19,049 +4.9 Mar 25,143 25,546 -1.6 Apr 28,001 25,043 +11.8 May 28,653 26,764 +7.1 Jun 29,529 28,995 +1.8 Jul Aug Sep YTD 245,200 236,799 +3.5 Route 50 - Norfolk Two daily roundtrips between Norfolk, VA and Washington, D.C./Northeast Corridor Ridership Month FFY19 FFY18 % Chg. -

Memorandum ML-84-24 a R C H 2 ' 1 9 8 4

UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT RAILROAD RETIREMENTBOARD March 2 , Memorandum ML-84-24 a r c h 2 ' 1 9 8 4 TO : Director of Compensation and Certification f r o m : Deputy General Counsel SU BJE C T: Auto-Train Corporation Employer Status - Termination This is in response to your request of January 18, 1984, for an opinion as to the status of Auto-Train Corporation as an employer under the Railroad Unemployment Insurance and Railroad Retirement Acts. This company has previously been held to be an employer, under those Acts and appears in the Employer Status Book as Item No. 387.2, with service creditable from December 6, 1971 to date. Auto-Train was organized for the purpose of providing transportation of passengers and their autos non-stop by rail between Virginia and Florida. In Auto-Train Corp., Operation Rail & Passenger Automobile Transport Service, Between Alexandria, Va., and Sanford, Fla., 342 ICC 533, (1971), the Interstate Commerce Commission held Auto-Train to be a carrier subject to the jurisdiction of the Commission. Based on this determination, the General Counsel held Auto-Train to be an employer under the Acts as a carrier subject to Part I of the Interstate Commerce Act. See L-71-290. On September 8, 1980, Auto-Train filed a petition to reorganize under Chapter 11 of the Federal bankruptcy laws. In a letter dated December 23, 1983, Ms. Imogene Lehman, of the law firm which is acting as Counsel to the Trustee, stated that the United States Bankruptcy Court for the District of Columbia directed that Auto-Train terminate its rail operations as of May 1, 1981. -

Summer 2020 ESPA Newsletter

S U M M E R 2 0 2 0 V O L . 4 5 N O . 3 ESPA Working For A Balanced EXPRESS Public Transportation News From The Network For New Yorkers www.esparail.org Empire State Passengers Association NYS Ridership Slowly Coming Back Gary Prophet Empire Service ridership, which is the ridership that travels solely Albany and south, has decreased 74% comparing February 2020 to July 2020, but that has improved from the 96% decrease in ridership from February to April. The ridership on the Empire Corridor west of Albany, which was down 90% February to April, is now down only 50% from February to July. The Lake Shore Limited, which was down 85% in April, is now down only 25% when February is compared to July. For Amtrak nationwide, comparing February to July, the Long Distance trains are down 62%, the state corridors down 83%, and the Northeast Corridor (Boston-NY-WashDC) is down In This Issue... 87%. So, New York State ridership, when compared to the NEC, is doing well and the long distance trains, especially the Portal Bridge Advances Lake Shore Limited, are performing much better than the Northeast Corridor and state corridors. Lake Shore Limited To Go Tri-Weekly Lake Shore Limited Going Tri-Weekly Gary Prophet Despite the relative good performance of the long distance Introduing New ESPA Website trains, Amtrak announced that most long distance trains, would be reduced to 3 times a week in October. The Auto-Train will remain daily and the Silver Meteor has already been reduced to Metro North & LIRR Face Crisis 4 days a week, and the Silver Star has already been reduced to 3 days a week.