Analysis of Cost Savings on Amtrak's Long-Distance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GAO-02-398 Intercity Passenger Rail: Amtrak Needs to Improve Its

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Honorable Ron Wyden GAO U.S. Senate April 2002 INTERCITY PASSENGER RAIL Amtrak Needs to Improve Its Decisionmaking Process for Its Route and Service Proposals GAO-02-398 Contents Letter 1 Results in Brief 2 Background 3 Status of the Growth Strategy 6 Amtrak Overestimated Expected Mail and Express Revenue 7 Amtrak Encountered Substantial Difficulties in Expanding Service Over Freight Railroad Tracks 9 Conclusions 13 Recommendation for Executive Action 13 Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 13 Scope and Methodology 16 Appendix I Financial Performance of Amtrak’s Routes, Fiscal Year 2001 18 Appendix II Amtrak Route Actions, January 1995 Through December 2001 20 Appendix III Planned Route and Service Actions Included in the Network Growth Strategy 22 Appendix IV Amtrak’s Process for Evaluating Route and Service Proposals 23 Amtrak’s Consideration of Operating Revenue and Direct Costs 23 Consideration of Capital Costs and Other Financial Issues 24 Appendix V Market-Based Network Analysis Models Used to Estimate Ridership, Revenues, and Costs 26 Models Used to Estimate Ridership and Revenue 26 Models Used to Estimate Costs 27 Page i GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking Appendix VI Comments from the National Railroad Passenger Corporation 28 GAO’s Evaluation 37 Tables Table 1: Status of Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions, as of December 31, 2001 7 Table 2: Operating Profit (Loss), Operating Ratio, and Profit (Loss) per Passenger of Each Amtrak Route, Fiscal Year 2001, Ranked by Profit (Loss) 18 Table 3: Planned Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions 22 Figure Figure 1: Amtrak’s Route System, as of December 2001 4 Page ii GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking United States General Accounting Office Washington, DC 20548 April 12, 2002 The Honorable Ron Wyden United States Senate Dear Senator Wyden: The National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) is the nation’s intercity passenger rail operator. -

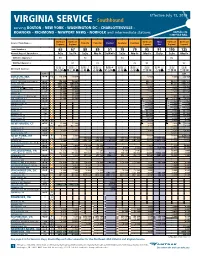

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

The ESPA EXPRESS NEWS from the EMPIRE STATE PASSENGERS ASSOCIATION

The ESPA EXPRESS NEWS FROM THE EMPIRE STATE PASSENGERS ASSOCIATION http://www.esparail.org WORKING FOR A MORE BALANCED TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM Vol. 35 No. 6 November/December 2011 Amtrak to Lease 85 Miles of Empire possibly changing the Lake Shore Limited schedule by departing Corridor from CSX Chicago 3 hours earlier and also departing New York about an hour earlier. One improvement considered would extend the In an extremely welcomed announcement, it was confirmed hours of the Diner to encourage more purchases, and to make on October 18 that Amtrak intends to enter into a long-term the Diner cashless (Debit/Credit cards only), which would save lease with CSX to gain full operational control of the 85 route time counting and tracking cash. Forty seven percent of the miles of the Empire Corridor between Control Point 75 north Diner guests are coach passengers, which is very high compared of Poughkeepsie (the north end of Metro-North territory) and to other Amtrak routes. Upgrading the food in the lounge car CP 160 at the Schenectady station. Amtrak already controls the also will be considered. Of interest in the report was that 62% 9 mile segment west of Schenectady to Hoffmans at CP 169 of the Lake Shore’s passengers are female and that 61% of where the CSX freight line from Selkirk Yard joins the main passengers are traveling alone. The top three city pairs on the line heading west. CSX will retain full freight rights on the Lake Shore Limited are: New York-Chicago, Buffalo-Chicago, leased line. and Syracuse-Chicago. -

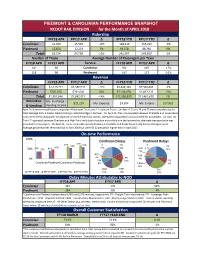

Piedmont and Carolinian Performance Snapshot

PIEDMONT & CAROLINIAN PERFORMANCE SNAPSHOT NCDOT RAIL DIVISION for the Month of APRIL 2018 Ridership FFY18 APR FFY17 APR Δ FFY18 YTD FFY17 YTD Δ Carolinian 21,060 25,525 -17% 148,219 155,219 -5% Piedmont 12,654 12,233 3% 93,378 88,284 6% Total 33,714 37,758 -11% 241,597 243,503 -1% Number of Trains Average Number of Passengers per Train FFY18 APR FFY17 APRService FFY18 APR FFY17 APR Δ 60 60 Carolinian 351 425 -17% 118 96 Piedmont 107 127 -16% Revenue FFY18 APR FFY17 APR Δ FFY18 YTD FFY17 YTD Δ Carolinian $1,310,771 $1,586,931 -17% $9,442,344 $9,564,446 -1% Piedmont $287,075 $261,040 10% $2,144,476 $1,897,232 13% Total $1,597,846 $1,847,971 -14% $11,586,820 $11,461,678 1% Amenities Mo. Surcharge + $21,214 Mo. Expense $3,304 Mo. Surplus $17,910 & Vending Vending Income April 2018 service modifications impacted 4 Piedmont Trains and 2 Carolinian Trains. On April 4, Trains 74 and 75 were cancelled due to track damage from a tractor trailer striking a railroad bridge in Durham. On April 15, Train 76 operated between Charlotte and Greensboro only due to trees and powerlines downed across the tracks by storms; alternate transportation was provided for passengers. On April 18, Train 74 operated between Charlotte and High Point only due to traction motor failure in the locomotive; alternate transportation was provided for passengers. On April 22, Trains 79 and 80 operated between Charlotte and Rocky Mount only due to CSX signal work. -

Equipment Roster

Location 3400 NE Grand Blvd. Oklahoma City, OK 73111 (405) 424-8222 Conveniently located just a half mile west of Interstate 35 off Exit 131 (NE 36th Street), on historic Grand Boulevard. - Half-mile east of Martin Luther King Boulevard - Just south of Lincoln Park Golf Course - 1 mile south of the Oklahoma City Zoo Oklahoma Railway Museum 3400 NE Grand Blvd. Oklahoma City, OK 73111 (405) 424-8222 www.oklahomarailwaymuseum.org EQUIPMENT ROSTER 40 1 Oklahoma Railway Museum The Oklahoma Railway Museum, Ltd. Bridge Logos (ORM) offers 35-minute excursion trains on the first and third Saturdays of each month for the public from 10 am until 4 pm starting the first Saturday in April. The trains leave the historic Oakwood Depot at 9:15, 11:15, 1:15 and 3:15 The Museum itself is open Thursday - Saturday from 9 am to 4 pm and there is no admission charge to tour the grounds. Train rides are free for children under the age of 3, $5 for children 3 years to 12 years, and These Frisco and Rock Island Railroad $12 for those 13 years and older. In heralds were displayed for almost 80 years addition to the train ride, railroad (1931-2010) on Oklahoma City’s South equipment, including motor cars, Robinson Street Bridge. The bridge was locomotives and passenger cars, are on located approximately a half mile east of display. A display car contains permanent Union Station and allowed both railroads to exhibits of railroad memorabilia. pass above Robinson to access to the station. The bridge was torn down to make Oakwood Station way for a new bridge with the rerouting of the I-40 crosstown expressway. -

40Thanniv Ersary

Spring 2011 • $7 95 FSharing tihe exr periencste of Fastest railways past and present & rsary nive 40th An Things Were Not the Same after May 1, 1971 by George E. Kanary D-Day for Amtrak 5We certainly did not see Turboliners in regular service in Chicago before Amtrak. This train is In mid April, 1971, I was returning from headed for St. Louis in August 1977. —All photos by the author except as noted Seattle, Washington on my favorite train to the Pacific Northwest, the NORTH back into freight service or retire. The what I considered to be an inauspicious COAST LIMITED. For nearly 70 years, friendly stewardess-nurses would find other beginning to the new service. Even the the flagship train of the Northern Pacific employment. The locomotives and cars new name, AMTRAK, was a disappoint - RR, one of the oldest named trains in the would go into the AMTRAK fleet and be ment to me, since I preferred the classier country, had closely followed the route of dispersed country wide, some even winding sounding RAILPAX, which was eliminat - the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804, up running on the other side of the river on ed at nearly the last moment. and was definitely the super scenic way to the Milwaukee Road to the Twin Cities. In addition, wasn’t AMTRAK really Seattle and Portland. My first association That was only one example of the serv - being brought into existence to eliminate with the North Coast Limited dated to ices that would be lost with the advent of the passenger train in America? Didn’t 1948, when I took my first long distance AMTRAK on May 1, 1971. -

NORTHEAST CORRIDOR New York - Washington, DC

NORTHEAST CORRIDOR New York - Washington, DC September 5, 2017 NEW YORK and WASHINGTON, DC NEW YORK - NEWARK - TRENTON PHILADELPHIA - WILMINGTON BALTIMORE - WASHINGTON, DC and intermediate stations Acela Express,® Reserved Northeast RegionalSM and Keystone Service® THIS TIMETABLE SHOWS ALL AMTRAK SERVICE FROM BOSTON OR SPRINGFIELD TO POINTS NEW YORK THROUGH WASHINGTON, DC. Also see Timetable Form W04 for complete Boston/Springfield to Washington, DC schedules, and Timetable Form W06 for service to Virginia locations. FALL HOLIDAYS Special Thanksgiving timetables for the period, November 20 through 27, 2017, will appear on Amtrak.com shortly and temporarily supersede these schedules. 1-800-USA-RAIL Amtrak.com Amtrak is a registered service mark of the National Railroad Passenger Corporation. National Railroad Passenger Corporation, Washington Union Station, 60 Massachusetts Ave. N.E., Washington, DC 20002. NRPC Form W2–Internet only–9/5/17. Schedules subject to change without notice. Depart Depart Depart Depart Depart Arrive Depart Depart Depart Depart Depart Arrive Train Name/Number Frequency New York Newark Newark Intl. Air. Metropark Trenton Philadelphia Philadelphia Wilmington Baltimore BWI New Carrollton Washington Northeast Regional 67 Mo-Fr 3 25A 3 45A —— 4 00A 4 25A 4 52A 5 00A 5 22A 6 10A 6 25A 6 40A 7 00A Northeast Regional 151 Mo-Fr 4 40A R4 57A —— 5 12A 5 35A 6 04A 6 07A 6 28A 7 27A 7 40A D7 59A 8 14A Northeast Regional 111 Mo-Fr 5 30A R5 46A —— 6 00A 6 26A 6 53A 6 55A 7 15A 8 00A 8 15A D8 29A 8 50A Acela Express 2103 Mo-Fr -

PRIIA Report

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2020 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2020) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2020 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A. -

CAPITOL LIMITED Train Time Schedule & Line Route

CAPITOL LIMITED train time schedule & line map Capitol Limited View In Website Mode The train line Capitol Limited has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chicago Union Station: 4:05 PM (2) Washington Union Station: 7:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest CAPITOL LIMITED train station near you and ƒnd out when is the next CAPITOL LIMITED train arriving. Direction: Chicago Union Station CAPITOL LIMITED train Time Schedule 16 stops Chicago Union Station Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 4:05 PM Monday 4:05 PM Union Station 50 Massachusetts Avenue Ne, Washington Tuesday 4:05 PM Rockville Amtrak Wednesday 4:05 PM 250 Rockville Pike, Rockville Thursday 4:05 PM Harpers Ferry Amtrak Friday 4:05 PM 182 Potomac St, Harpers Ferry Saturday 4:05 PM Martinsburg Amtrak Station 229 East Martin Street, Berkeley County Cumberland Amtrak Station 200 Park St, Cumberland CAPITOL LIMITED train Info Direction: Chicago Union Station Connellsville Amtrak Stops: 16 Trip Duration: 1060 min Pittsburgh Amtrak Station Line Summary: Union Station, Rockville Amtrak, 1100 Liberty Avenue, Pittsburgh Harpers Ferry Amtrak, Martinsburg Amtrak Station, Cumberland Amtrak Station, Connellsville Amtrak, Alliance Amtrak Pittsburgh Amtrak Station, Alliance Amtrak, Cleveland, Elyria Amtrak, Sandusky Amtrak Station, Cleveland Toledo, Waterloo Amtrak Station, Elkhart Amtrak 200 Cleveland Memorial Shoreway, Cleveland Station, South Bend Amtrak Station, Chicago Union Station Elyria Amtrak 410 East River Road, Elyria Sandusky Amtrak Station -

Bilevel Rail Car - Wikipedia

Bilevel rail car - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bilevel_rail_car Bilevel rail car The bilevel car (American English) or double-decker train (British English and Canadian English) is a type of rail car that has two levels of passenger accommodation, as opposed to one, increasing passenger capacity (in example cases of up to 57% per car).[1] In some countries such vehicles are commonly referred to as dostos, derived from the German Doppelstockwagen. The use of double-decker carriages, where feasible, can resolve capacity problems on a railway, avoiding other options which have an associated infrastructure cost such as longer trains (which require longer station Double-deck rail car operated by Agence métropolitaine de transport platforms), more trains per hour (which the signalling or safety in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The requirements may not allow) or adding extra tracks besides the existing Lucien-L'Allier station is in the back line. ground. Bilevel trains are claimed to be more energy efficient,[2] and may have a lower operating cost per passenger.[3] A bilevel car may carry about twice as many as a normal car, without requiring double the weight to pull or material to build. However, a bilevel train may take longer to exchange passengers at each station, since more people will enter and exit from each car. The increased dwell time makes them most popular on long-distance routes which make fewer stops (and may be popular with passengers for offering a better view).[1] Bilevel cars may not be usable in countries or older railway systems with Bombardier double-deck rail cars in low loading gauges. -

Crescent Corridor Update

Crescent Corridor Update December 21st, 2016 US DOT Talking Freight Norfolk Southern Government Relations Norfolk Southern’s Network • NS operates approximately 20,000 route miles throughout 22 states and the District of Columbia • Engaged in the rail transportation of raw materials, intermediate products, and finished goods • Operates the most extensive intermodal network in the East and is a major transporter of coal and industrial products. • NYSE: NSC 2 NS Intermodal Network Growth Majority of growth has been over Corridors • Norfolk Southern has A Network of Key Corridors employed a “Corridor Albany Boston Detroit Strategy” focusing on four Bethlehem Chicago New York/New Jersey Harrisburg Philadelphia key principles: Columbus Greencastle • Market access Cincinnati • Length of haul Charlotte Memphis • Asset utilization Atlanta Birmingham • Productivity Shreveport New Orleans What is an Intermodal Facility? Intermodal Facility –A rail terminal for transferring freight from one transportation mode to another, either from truck‐to‐rail or rail‐to‐truck for the Crescent Corridor, without the handling of the freight itself when changing modes. NS’ Intermodal Network Norfolk Southern System Intermodal Terminal(s) Market Expansions thru 2010 Market Expansions thru 2012 IM Port Terminal TCS Terminals Total U.S. Intermodal Units (Originated Units) 16,000,000 14,000,000 12,000,000 10,000,000 8,000,000 6,000,000 4,000,000 2,000,000 0 *2016 is Jan-Nov annualized Source: AAR Crescent Corridor Pre-Project Influences • Norfolk Southern – Continued cooperation with long-haul truck carriers – Increase in freight trade between Northeast and South – Infrastructure enhancements for speed and capacity • Key Drivers for Private, Local, State, and Federal Partners – Increased highway congestion and vehicular emissions – Growing vehicle travel miles and congestion on I-81, I- 40, I-85, I-20, and I-76. -

Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2019 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2019) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2019 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A.