Artisan Cooperatives in Oaxaca, Mexico a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intro Alebrije.Pdf

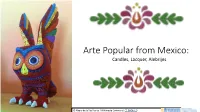

Arte Popular from Mexico: Candles, Lacquer, Alebrijes © Alvaro de la Paz Franco / Wikimedia Commons/ CC BY-SA 4.0 What is arte popular? Arte Popular is a Spanish term that translates to Popular Art in English. Another word for Arte Popular is artesanias. These can be arts like paintings and pottery, but they also include food, dance, and clothes. These arts are unique to Mexico and the communities that live in it. After the Mexican Revolution of the 1910s, focus was turned to Native Amerindian and farming communities. These communities were creating works of art but they had been ignored. But, after the revolution, Mexico needed something that could unite the people of Mexico. They decided to use the traditional arts of its people. Arte popular/artesanias became the heart of Mexico. You can go to Mexico now and visit artists’ workshops and © Thelmadatter / Edgar Adalberto Franco Martinez Ayotoxco De Guerrero, Puebla at see how they create their beautiful art. the Encuentro de las Colecciones de Arte Popular Valoración y Retos at the Franz Mayer Museum in Mexico City / Wikimedia Commons/ CC BY-SA 4.0 Arte popular/artesanias are traditions of many years within their communities. It is this community aspect that has provided Mexico with an art that focuses on the everyday people. It is why the word ‘popular’ is used to label these kinds of arts. The amazing objects they create, whether it is ceramic bowls or painted chests, are all unique and specific to the communities This is why there is so much variety in Mexico, because it is a large country. -

Movements of Diverse Inquiries As Critical Teaching Practices Among Charros, Tlacuaches and Mapaches Stephen T

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 9-2012 Movements of Diverse Inquiries as Critical Teaching Practices Among Charros, Tlacuaches and Mapaches Stephen T. Sadlier University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Sadlier, Stephen T., "Movements of Diverse Inquiries as Critical Teaching Practices Among Charros, Tlacuaches and Mapaches" (2012). Open Access Dissertations. 664. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/664 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MOVEMENTS OF DIVERSE INQUIRIES AS CRITICAL TEACHING PRACTICES AMONG CHARROS, TLACUACHES AND MAPACHES A Dissertation Presented by STEPHEN T. SADLIER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION September 2012 School of Education Language, Literacy, and Culture © Copyright by Stephen T. Sadlier 2012 All Rights Reserved MOVEMENTS OF DIVERSE INQUIRIES AS CRITICAL TEACHING PRACTICES AMONG CHARROS,1 TLACUACHES2 AND MAPACHES3 A Dissertation Presented By STEPHEN T. SADLIER Approved as to style and content -

Descargue El Catálogo De Zonas Económicas Del Gobierno Federal

S H SUBSECRETARIA DE EGRESOS C P DIRECCION GENERAL DE NORMATIVIDAD Y DESARROLLO ADMINISTRATIVO CATALOGO DE ZONAS ECONOMICAS DEL GOBIERNO FEDERAL VIGENTE: A PARTIR DEL16 DE MAYO DE 1996 HOJA 1 DE 57 ENTIDAD CODIGO FEDERATIVA CLAVE I I CLAVE I I I MUNICIPIOS 01 AGUASCALIENTES B 001 AGUASCALIENTES 002 ASIENTOS 003 CALVILLO 004 COSIO 005 JESUS MARIA 006 PABELLON DE ARTEAGA 007 RINCON DE ROMOS 008 SAN JOSE DE GRACIA 009 TEPEZALA 010 LLANO, EL 011 SAN FRANCISCO DE LOS ROMO 02 BAJA CALIFORNIA B MUNICIPIOS 001 ENSENADA 002 MEXICALI 003 TECATE 004 TIJUANA 005 PLAYAS DE ROSARITO 03 BAJA CALIFORNIA SUR B MUNICIPIOS 001 COMONDU 002 MULEGE 003 PAZ, LA 004 CABOS, LOS 005 LORETO 04 CAMPECHE B MUNICIPIOS 001 CALKINI 002 CAMPECHE 003 CARMEN 004 CHAMPOTON 005 HECELCHAKAN 006 HOPELCHEN 007 PALIZADA 008 TENABO 009 ESCARCEGA 05 COAHUILA B MUNICIPIOS B MUNICIPIOS 004 ARTEAGA 001 ABASOLO 009 FRANCISCO I. MADERO 002 ACUÑA ZONIFICADOR-1996 D: CLAVE: A: POBLACIONES B: MUNICIPIOS S H SUBSECRETARIA DE EGRESOS C P DIRECCION GENERAL DE NORMATIVIDAD Y DESARROLLO ADMINISTRATIVO CATALOGO DE ZONAS ECONOMICAS DEL GOBIERNO FEDERAL VIGENTE: A PARTIR DEL16 DE MAYO DE 1996 HOJA 2 DE 57 ENTIDAD CODIGO FEDERATIVA CLAVE I I CLAVE I I I 05 COAHUILA B MUNICIPIOS B MUNICIPIOS 017 MATAMOROS 003 ALLENDE 024 PARRAS 005 CANDELA 030 SALTILLO 006 CASTAÑOS 033 SAN PEDRO 007 CUATROCIENEGAS 035 TORREON 008 ESCOBEDO 036 VIESCA 010 FRONTERA 011 GENERAL CEPEDA 012 GUERRERO 013 HIDALGO 014 JIMENEZ 015 JUAREZ 016 LAMADRID 018 MONCLOVA 019 MORELOS 020 MUZQUIZ 021 NADADORES 022 NAVA 023 OCAMPO -

Mexico NEI-App

APPENDIX C ADDITIONAL AREA SOURCE DATA • Area Source Category Forms SOURCE TYPE: Area SOURCE CATEGORY: Industrial Fuel Combustion – Distillate DESCRIPTION: Industrial consumption of distillate fuel. Emission sources include boilers, furnaces, heaters, IC engines, etc. POLLUTANTS: NOx, SOx, VOC, CO, PM10, and PM2.5 METHOD: Emission factors ACTIVITY DATA: • National level distillate fuel usage in the industrial sector (ERG, 2003d; PEMEX, 2003a; SENER, 2000a; SENER, 2001a; SENER, 2002a) • National and state level employee statistics for the industrial sector (CMAP 20-39) (INEGI, 1999a) EMISSION FACTORS: • NOx – 2.88 kg/1,000 liters (U.S. EPA, 1995 [Section 1.3 – Updated September 1998]) • SOx – 0.716 kg/1,000 liters (U.S. EPA, 1995 [Section 1.3 – Updated September 1998]) • VOC – 0.024 kg/1,000 liters (U.S. EPA, 1995 [Section 1.3 – Updated September 1998]) • CO – 0.6 kg/1,000 liters (U.S. EPA, 1995 [Section 1.3 – Updated September 1998]) • PM – 0.24 kg/1,000 liters (U.S. EPA, 1995 [Section 1.3 – Updated September 1998]) NOTES AND ASSUMPTIONS: • Specific fuel type is industrial diesel (PEMEX, 2003a; ERG, 2003d). • Bulk terminal-weighted average sulfur content of distillate fuel was calculated to be 0.038% (PEMEX, 2003d). • Particle size fraction for PM10 is assumed to be 50% of total PM (U.S. EPA, 1995 [Section 1.3 – Updated September 1998]). • Particle size fraction for PM2.5 is assumed to be 12% of total PM (U.S. EPA, 1995 [Section 1.3 – Updated September 1998]). • Industrial area source distillate quantities were reconciled with the industrial point source inventory by subtracting point source inventory distillate quantities from the area source distillate quantities. -

Finding Aid for the Lola Alvarez Bravo Archive, 1901-1994 AG 154

Center for Creative Photography The University of Arizona 1030 N. Olive Rd. P.O. Box 210103 Tucson, AZ 85721 Phone: 520-621-6273 Fax: 520-621-9444 Email: [email protected] URL: http://creativephotography.org Finding aid for the Lola Alvarez Bravo Archive, 1901-1994 AG 154 Finding aid updated by Meghan Jordan, June 2016 AG 154: Lola Alvarez Bravo Archive, 1901-1994 - page 2 Lola Alvarez Bravo Archive, 1901-1994 AG 154 Creator Bravo, Lola Alvarez Abstract Photographic materials (1920s-1989) of the Mexican photographer Lola Alvarez Bravo (1903 [sometimes birth date is recorded as 1907] -1993). Includes extensive files of negatives from throughout her career. A small amount of biographical materials, clippings, and publications (1901-1994) are included. The collection has been fully processed. A complete inventory is available. Quantity/ Extent 32 linear feet Language of Materials Spanish English Biographical Note Lola Álvarez Bravo was born Dolores Martínez de Anda in 1903 in Lagos de Moreno, a small city in Jalisco on Mexico's Pacific coast. She moved to Mexico City as a young child, after her mother left the family under mysterious circumstances. Her father died when she was a young teenager, and she was then sent to live with the family of her half brother. It was here that she met the young Manuel Alvarez Bravo, a neighbor. They married in 1925 and moved to Oaxaca where Manuel was an accountant for the federal government. Manuel had taken up photography as an adolescent; he taught Lola and they took pictures together in Oaxaca. Manuel also taught Lola how to develop film and make prints in the darkroom. -

Craft Traditions of Oaxaca with Cabot's Pueblo Museum

Craft Traditions of Oaxaca with Cabot’s Pueblo Museum Oaxaca CRAFT TRADITIONS September 14-21. 2018 Duration: 8 Days / 7 Nights Cultural Journeys Mexico | Colombia | Guatemala www.tiastephanietours.com | (734) 769 7839 Craft Traditions of Oaxaca with Cabot’s Pueblo Museum Oaxaca CRAFT TRADITIONS Join us on an extraordinary journey with Cabot’s Pueblo Museum to explore the culture, arts and crafts of Oaxaca. Based in Oaxaca City, we’ll visit communities of the Central Valleys, where we’ll meet the wonderful artisans featured here at the Museum! In San Bartolo Coyotepec, known for its black pottery, we’ll join Magdalena Pedro Martinez, to see how the soil from the region is masterfully transformed into beautiful pots and sculptures. In San Martin Tilcajete and San Antonio Arrazola, known for whimsical carved wood animals and “alebrijes”, we’ll join Julia Fuentes, Eleazar Morales and Mario Castellanos. In Teotitlan del Valle, the legendary “tapestry” weaving town, we’ll visit the family of recognized artisan, Porfirio Gutierrez, who recently has been recognized by the Smithson- ian Institution for his work with his ancient family and Zapotec community traditions of using natural dyes in their weavings. We’ll meet Yesenia Salgado Tellez too, who will help us understand the historic craft of filigree jewelry. Join us on this very special opportunity to travel with Cabot’s Pueblo Museum to explore the craft traditions and meet the arti- sans of Oaxaca! Program Highlights • Oaxaca City Tour • Tlacolula Market, Afternoon with Porfirio Gutierrez and Family. • Monte Alban, Arrazola and Atzompa, LOCATION Lunch at La Capilla. • Ocotlan and the Southern Craft Route. -

Travel-Guide-Oaxaca.Pdf

IHOW TO USE THIS BROCHURE Tap this to move to any topic in the Guide. Tap this to go to the Table of Contents or the related map. Índex Map Tap any logo or ad space for immediate access to Make a reservation by clicking here. more information. RESERVATION Déjanos mostrarte los colores y la magia de Oaxaca Con una ubicación estratégica que te permitirá disfrutar los puntos de interés más importantes de Oaxaca y con un servicio que te hará vivir todo el arte de la hospitalidad, el Hotel Misión Oaxaca es el lugar ideal para el viaje de placer y los eventos sociales. hotelesmision.com Tap any number on the maps and go to the website Subscribe to DESTINATIONS MEXICO PROGRAM of the hotel, travel agent. and enjoy all its benefits. 1 SUBSCRIPTION FORM Weather conditions and weather forecast Walk along the site with Street View Enjoy the best vídeos and potos. Come and join us on social media! Find out about our news, special offers, and more. Plan a trip using in-depth tourist attraction information, find the best places to visit, and ideas for an unforgettable travel experience. Be sure to follow us Index 1. Oaxaca. Art & Color. 24. Route to Mitla. 2. Discovering Oaxaca. Tour 1. 25. Route to Mitla. 3. Discovering Oaxaca. Tour 1. Hotel Oaxaca Real. 26. Route to Mitla. Map of Mitla. AMEVH. 4. Discovering Oaxaca. Tour 1. 27. Route to Monte Albán - Zaachila. Oro de Monte Albán (Jewelry). 28. Route to Monte Albán - Zaachila. 5. Discovering Oaxaca. Tour 1. Map of Monte Albán. -

Ceramica: Mexican Pottery of the 20Th Century Ebook

CERAMICA: MEXICAN POTTERY OF THE 20TH CENTURY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Amanda Thompson | 208 pages | 01 Jan 2001 | Schiffer Publishing Ltd | 9780764312489 | English | Atglen, United States CerAmica: Mexican Pottery of the 20th Century PDF Book Garcia Quinones has won prizes for his work since he was a boy and each year for thirty year has sold his wars at the annual Christmas Bazaar at the Deportivo Venustiano Carranza sports facility. A marble vase from the s. They were used to serve first class passengers and are made of white stoneware with the red continental airlin Bjorn Wiinblad for Rosenthal ceramic pitcher and cups. In addition to majolica, two large factories turn out hand painted ceramics of the kaolin type. This permits many artisans to sell directly, cutting out middlemen. By Charles Catteau for Boch Freres. When creating a southwest Mexican rustic home decor, talavera pottery can add a gorgeous finishing touch. The best known forms associated with Metepec are its Trees of Life, mermaids and animals such as lions, horses with or without wings and ox teams. Today, her pieces are part of Atzompa's pottery traditions even though she herself is outsold by younger potters who produce cheaper and better wares. These are Bram and Dosa in the city a Guanajuato and the town of Marfil respectively. Indigenous traditions survive in a few pottery items such as comals , and the addition of indigenous design elements into mostly European motifs. Uh-oh, it looks like your Internet Explorer is out of date. There has also been experimentation with new glaze colors, such as blue and mauve. -

OAXACA PROFUNDO a Memorable Journey Into

OAXACA PROFUNDO A memorable journey into the real Oaxaca March 9-16, 2019 With over 30 years experience taking groups to Oaxaca, organizing conferences there , and making presentations ourselves, Ward and Tot Albro and their Tierra del Sol: Mexico Programs and Services are uniquely qualified to give you the opportunity to share an incredible week learning why Oaxaca is THE PLACE to visit in Mexico. A still active historian who has published widely on Mexican history and culture, Ward Albro has long been identified with Oaxacan history, art, and folk art. His wife, Tot, a public school teacher in San Antonio, brings special expertise in textiles, weavings, and folk art. Her Albros Casa y Garden, the store she operated in Castroville, Texas, for many years, was widely known for the Oaxacan products featured there. Both of them treasure the personal relations they have developed over the years with many artists, artisans, scholars, and just great people in Oaxaca. THE PROGRAM During the week we will be visiting numerous artists and artisans in their homes and workshops and we will also bring experts to visit with us at our bed and breakfast. We will also have several excursions to archeological and historic sites. The program will include, but not be limited, to the following: *Guided visit to the Regional Museum in the Santo Domingo *Guided visit to Monte Alban and Mitla, two of Mexico’s premier archeological sites, with Dr. Pedro Javier Torres Hernandez *Visit to Jacobo and Maria Angeles’s wood carving workshop in San Martin Tilcajete. Jacobo and Maria’s work is world famous. -

Cabot's Museum Oaxaca Craft Sept 8 2017

Tia Stephanie Tours Craft Traditions of Oaxaca Cabot’s Pueblo Museum September 8-15, 2017 (7 Nights) Join us on an extraordinary journey with Cabot's Pueblo Museum to explore the culture, arts and crafts of Oaxaca. Based in Oaxaca City, we’ll visit communities of the Central Valleys, where we'll meet the wonderful artisans featured here at the museum! In San Bartolo Coyotepec, known for its black pottery, we'll join Magdalena Pedro Martinez to see how the soil from the region is masterfully transformed into beautiful pots and sculptures. In San Martin Tilcajete and San Antonio Arrazola, known for whimsical carved wood animals and "alebrijes," we'll join Julia Fuentes, Eleazar Morales and Mario Castellanos. In Teotitlan del Valle, the legendary "tapestry" weaving town, we'll visit the family of recognized artisan, Porfirio Gutierrez, recently awarded by the Smithsonian Institution for his work with his ancient family and Zapotec community in the revival and use of natural dyes in their weavings. We'll meet Yesenia Salgado Tellez too, who will help us understand the historic craft of filigree jewelry. We'll also visit workshops of some extraordinary emerging artisans, explore vibrant markets, experience fabulous regional cuisine and enjoy special museum and gallery tours. Join us on this very special opportunity to travel with Cabot's Pueblo Museum to explore Oaxaca's famous craft traditions and meet the artisans of Oaxaca! Day One: Friday, September 8, Arrive Oaxaca City (D) Transfer to our charming and centrally located hotel. Tonight we enjoy a festive welcome dinner to explore the culinary world of the seven moles at Los Pacos! www.tiastephanietours.com (734) 769-7839 Page 1 Day Two: Saturday, September 9, Oaxaca City Tour: (B, L) • Explore Oaxaca City, UNESCO World Heritage Site, and our home base. -

A Day in Oaxaca"

"A Day in Oaxaca" Created by: Cityseeker 4 Locations Bookmarked Monte Albán "Zapotec Legacy" Wedged between stark elemental features – blue skies and an ochre, parched terra – Monte Albán sits on a flattened promontory, exemplifying nearly 1500 years of pre-Columbian civilization. Monte Albán rises 400 meters (1300 feet) above the valley floor of Oaxaca, and a wave of history, dominated by the cultures of Olmecs, Zapotecs and Mixtecs sweeps by User: (WT-shared) through its pyramidal structures. Shrines, palaces, terraced platforms, Anyludes atwts wikivoyage tombs and mounds are scattered across this significant archaeological site, each pointing to Monte Albán's central role in Mesoamerican civilization. At the core of this complex is the Main Plaza, a monumental structure that is dominated by a series of stairs that amble up its southern platform, while small temples, residences and ballcourts are strewn across its surroundings. Several stone structures indicate that morbid sacrificial activities and ceremonies were conducted here. One of the earliest examples of these structures are the Danzantes, a set of figures that harken to the Olmec culture. A few important stone etchings and carvings found on the site have been encased within an on-site museum. Carretera Oaxaca-Monte Albán, 8 kilometers west of Oaxaca City, Oaxaca Árbol del Tule "Magnificent & Ancient Flora" The Árbol del Tule is a gigantic ahuehuete, or cypress, tree located in the town of Santa Maria del Tule, 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) east of Oaxaca City. This legendary tree measures 36.2 meters around and is anywhere from 1200 to 3000 years old. The tree reportedly grows on a sacred Zapotec site. -

Mexican Folk Art and Culture

Mexican Folk Art Mexican Folk Art Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Based in part by the exhibition Tesoros Escondidos: Hidden Treasures from the Mexican Collections curated by Ira Jacknis, Research Anthropologist, Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. Object Photography: Therese Babineau Intern assistance: Elizabeth Lesch Copyright © 2004. Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology and the Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. This publication was made possible in part by a generous grant from the William Randolph Hearst Foundation. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY TABLE OF CONTENTS Mexico 4 Map 5 Ancient Mexico 6 The Spanish Conquest 8 The Mexican Revolution and Renaissance 10 Folk Art 11 Masks 13 Pottery 17 Laquerware 21 Clothing and Textiles 24 Baskets, Gourds and Glass 28 Female figurine. Made by Teodora Blanco; Toys and Miniatures 30 Santa María Atzompa, Oaxaca. Teodora Paper Arts 33 Blanco (1928-80) was a major Mexican folk artist. While in her late twenties she began Tin and Copper 35 to make her female figurines, for which she is best known. This pot-carrying figure wears Art of the Huichol 36 a Oaxacan shawl around her head. Oaxacan Woodcarving 38 Fireworks 39 Food 40 Day of the Dead 43 Vocabulary 47 Review Questions 48 Bibliography 50 3 MEXICAN FOLK ART PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Mexico Mexico is very diverse geographically. It is made up of fertile valleys, tropical forests, high mountain peaks, deep canyons, and desert landscapes. Clockwise: Pacific coast, south of Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, 1996. Lake Pátzcuaro, as seen from Tzintzuntzan, Michoacán, 1996.