Mexican Folk Art and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Huichol) of Tateikita, Jalisco, Mexico

ETHNO-NATIONALIST POLITICS AND CULTURAL PRESERVATION: EDUCATION AND BORDERED IDENTITIES AMONG THE WIXARITARI (HUICHOL) OF TATEIKITA, JALISCO, MEXICO By BRAD MORRIS BIGLOW A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2001 Copyright 2001 by Brad Morris Biglow Dedicated to the Wixaritari of Tateikita and the Centro Educativo Tatutsi Maxa Kwaxi (CETMK): For teaching me the true meaning of what it is to follow in the footsteps of Tatutsi, and for allowing this teiwari to experience what you call tame tep+xeinuiwari. My heart will forever remain with you. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee members–Dr. John Moore for being ever- supportive of my work with native peoples; Dr. Allan Burns for instilling in me the interest and drive to engage in Latin American anthropology, and helping me to discover the Huichol; Dr. Gerald Murray for our shared interests in language, culture, and education; Dr. Paul Magnarella for guidance and support in human rights activism, law, and intellectual property; and Dr. Robert Sherman for our mutual love of educational philosophy. Without you, this dissertation would be a mere dream. My life in the Sierra has been filled with countless names and memories. I would like to thank all of my “friends and family” at the CETMK, especially Carlos and Ciela, Marina and Ángel, Agustín, Pablo, Feliciano, Everardo, Amalia, Rodolfo, and Armando, for opening your families and lives to me. In addition, I thank my former students, including los chavos (Benjamín, Salvador, Miguel, and Catarino), las chicas (Sofía, Miguelina, Viviana, and Angélica), and los músicos (Guadalupe and Magdaleno). -

The Reorganization of the Huichol Ceremonial Precinct (Tukipa) of Guadalupe Ocotán, Nayarit, México Translation of the Spanish by Eduardo Williams

FAMSI © 2007: Víctor Manuel Téllez Lozano The Reorganization of the Huichol Ceremonial Precinct (Tukipa) of Guadalupe Ocotán, Nayarit, México Translation of the Spanish by Eduardo Williams Research Year : 2005 Culture : Huichol Chronology : Modern Location : Nayarit, México Site : Guadalupe Ocotán Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Linguistic Note Introduction Architectural Influences The Tukipa District of Xatsitsarie The Revolutionary Period and the Reorganization of the Community The Fragmentation of the Community The Tukipa Precinct of Xatsitsarie Conclusions Acknowledgements Appendix: Ceremonial precincts derived from Xatsitsarie’s Tuki List of Figures Sources Cited Abstract This report summarizes the results of research undertaken in Guadalupe Ocotán, a dependency and agrarian community located in the municipality of La Yesca, Nayarit. This study explores in greater depth the political and ceremonial relations that existed between the ceremonial district of Xatsitsarie and San Andrés Cohamiata , one of three Wixaritari (Huichol) communities in the area of the Chapalagana River, in the northern area of the state of Jalisco ( Figure 1 , shown below). Moreover, it analyzes how the destruction of the Temple ( Tuki ) of Guadalupe Ocotán, together with the modification of the community's territory, determined the collapse of these ceremonial links in the second half of the 20th century. The ceremonial reorganization of this district is analyzed using a diachronic perspective, in which the ethnographic record, which begins with Lumholtz' work in the late 19th century, is contrasted with reports by missionaries and oral history. Similarly, on the basis of ethnographic data and information provided by archaeological studies, this study offers a reinterpretation of certain ethnohistorical sources related to the antecedents of these ceremonial centers. -

What Do People from Other Countries/Cultures Wear? 4-H Clothing and Textiles Project Part of the Family and Consumer Sciences 4-H Project Series

1-2 YEARS IN PROJECT What do People from Other Countries/Cultures Wear? 4-H Clothing and Textiles Project Part of the Family and Consumer Sciences 4-H Project Series Understanding Textiles (Fabric) Project Outcome: Global/ Ethnic- Identify various fabric as belonging to specific ethnic cultures. Project Indicator: Completed exploration of specific items worn in identified countries/cultures, the clothes worn during festivals/celebrations, and fabrics used. Do you know someone from another country? Or have you ever seen, in person or on TV, a festival or celebration from another country? Have you noticed that they wear clothes that are different from what you and I wear? While some of their celebrations are the same as ours, the clothes they wear may be different. It is fun and interesting to learn about what people from other countries wear during their festivals and celebrations. In learning this, you can also learn about the fabrics that they use to make their garments for these festivals. For this activity, you will learn about four different cultures, what they wear, especially for their festivals/celebrations or based on their religion, and what fabrics they make and use for clothing worn. Then you will be asked to do your own research to discover more about the clothing of these and other cultures. First, let’s define the word culture. Culture means: the beliefs and customs of a particular group of people which guides their interaction among themselves and others. A country can contain people from more than one cultural background. They may or may not observe the same celebrations or traditions in the same way. -

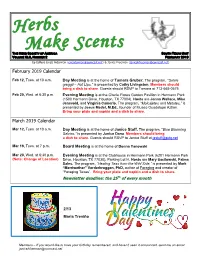

FEBRUARY 2019 Co-Editors Linda Alderman ([email protected]) & Janice Freeman ([email protected])

Herbs Make Scents THE HERB SOCIETY OF AMERICA SOUTH TEXAS UNIT VOLUME XLII, NUMBER 2 FEBRUARY 2019 Co-Editors Linda Alderman ([email protected]) & Janice Freeman ([email protected]) February 2019 Calendar Feb 12, Tues. at 10 a.m. Day Meeting is at the home of Tamara Gruber. The program, “Salvia greggii – Hot Lips,” is presented by Cathy Livingston. Members should bring a dish to share. Guests should RSVP to Tamara at 713-665-0675 Feb 20, Wed. at 6:30 p.m. Evening Meeting is at the Cherie Flores Garden Pavilion in Hermann Park (1500 Hermann Drive, Houston, TX 77004). Hosts are Jenna Wallace, Mike Jensvold, and Virginia Camerlo. The program, “Molcajetes and Metates,” is presented by Jesus Medel, M.Ed., founder of Museo Guadalupe Aztlan. Bring your plate and napkin and a dish to share. March 2019 Calendar Mar 12, Tues. at 10 a.m. Day Meeting is at the home of Janice Stuff. The program, “Blue Blooming Salvias,” is presented by Janice Dana. Members should bring a dish to share. Guests should RSVP to Janice Stuff at [email protected] Mar 19, Tues. at 7 p.m. Board Meeting is at the home of Donna Yanowski Mar 20, Wed. at 6:30 p.m. Evening Meeting is at the Clubhouse in Hermann Park (6201 Hermann Park (Note: Change of Location) Drive, Houston, TX 77030). Parking Lot H. Hosts are Mary Sacilowski, Palma Sales. The program, “Healing Teas from the Wild Side,” is presented by Mark “Merriwether” Vorderbruggen, PhD, author of Foraging and creator of “Foraging Texas”. Bring your plate and napkin and a dish to share. -

Mexican Elites and the Rights of Indians and Blacks in Nineteenth-Century New Mexico

UCLA Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review Title Off-White in an Age of White Supremacy: Mexican Elites and the Rights of Indians and Blacks in Nineteenth-Century New Mexico Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/42d5k043 Journal Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review, 25(1) ISSN 1061-8899 Author Gómez, Laura E. Publication Date 2005 DOI 10.5070/C7251021154 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ARTICLES OFF-WHITE IN AN AGE OF WHITE SUPREMACY: MEXICAN ELITES AND THE RIGHTS OF INDIANS AND BLACKS IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NEW MEXICOt LAURA E. GOMEZ, PH.D.* I. INTRODUCTION In their studies of mid-twentieth-century civil rights litiga- tion involving Chicanos, several scholars have reached the con- clusion that, in this era, Mexican Americans occupied an ambivalent racial niche, being neither Black nor white.1 The Su- preme Court case Hernandez v. Texas,2 decided in 1954 during t This article is dedicated to the current editors of the Chicano-LatinoLaw Review. Founded in 1972 in the midst of the Chicano Movement, the Chicano- Latino Law Review persists today during a period of retrenchment, with shrinking numbers of Latino students attending the only public law school in Southern California. That the journal thrives is a testament to the dedication and hard work of its editors. * Professor of Law & Sociology, UCLA. Ph.D. Stanford (1994), J.D. Stanford (1992), M.A. Stanford (1988), A.B. Harvard (1986). Weatherhead Resident Scholar, School of American Research (2004-2005). The author thanks the following individ- uals for their input: Rick Abel, Kip Bobroff, Tobias Duran, Lawrence Friedman, Carole Goldberg, Gillian Lester, Joel Handler, Ian Haney L6pez, Antonio G6mez, Michael Olivas, Est6van Rael-Gilvez, Leti Volpp, as well as audiences at the School of American Research and the "Hernandez at 50" Conference at the University of Houston Law Center. -

Santa Fe School of Cooking and Market 2005

Santa Fe School of Cooking and Market 2005 santafeschoolofcooking.com Chile Tiles on Back Cover NEW Savor Santa Fe Video— Traditional New Mexican Discover how easy it is to create both red and green chile sauces, enchiladas and the regional food that is indigenous to Santa Fe. Included in the 25-minute video is a full color booklet with photos for the featured recipes: chicken or cheese enchiladas, red and green chile sauce and corn tortillas. In addition, you will receive recipes for pinto beans, posole and bread pudding. After watching this video and creating the food in your own kitchen, you will feel The making of the video with host Nicole like you have visited Santa Fe and the Curtis Ammerman and chef Rocky Durham. School of Cooking. #1 $19.95 FIFTEEN YEARS AND STILL COOKIN!! That’s right. The Santa Fe School of Cooking will be 15 years old in December of 2004. We have seen lots of changes, but the School and Market have the same mission as the day it opened—promoting local agriculture and food products. To spread the word of our great food even further, we recently produced the first of a series of videos touting the glories of Santa Fe and its unique cuisine. Learn the tips and techniques of Southwestern cuisine from the Santa Fe School of Cooking right in your own home. Be sure and check out our great gift ideas for the holidays, birthdays, Father’s and Mother’s days or any day of the year. Our unique gifts are a sure way to send a special gift for a special person. -

Mexico's Indigenous and Folk Art Comes to Chapala

Mexico’s indigenous and folk art comes to Chapala Each year Experience Mex‐ECO Tours promotes a trip which we call the ‘Chapala Artisan Fair’, but this is much more than just a shopping trip; so what’s it really all about? The Feria Maestros del Arte (Masters of Art Fair) is the name given to this annual event in Chapala, and also the name of the non‐profit organization which puts in an incredible amount of work to make it happen. In 2002 an amazing lady called Marianne Carlson came up with the idea of bringing some of the artists and artisans she came across in rural Mexico to Ajijic to sell their high quality traditional work. After a successful first fair, with 13 artists being very well received by the public, Marianne decided to make this an annual event. Providing an outlet for traditional Mexican artists and artisans to sell their work, the Feria Maestros del Arte has provided many families with the opportunity to continue creating Experience Mex‐ECO Tours S.A. de C.V. | www.mex‐ecotours.com | info@mex‐ecotours.com their important cultural representations by allowing them to pursue this as a career, rather than seeking alternative employment. Here is their mission as a non‐profit organization: “To preserve and promote Mexican indigenous and folk art. We help preserve these art forms and the culture that produces them by providing the artists a venue to sell their work to galleries, collectors, museums and corporations. We promote regional and international awareness to the value of these endangered arts.” The efforts made by the Feria committee and its many volunteers mean that the artists and artisans not only have a chance to generate more income in a few days than they may otherwise generate in a year, but also the chance to be recognized by buyers and collectors from around the world. -

The Oppressive Pressures of Globalization and Neoliberalism on Mexican Maquiladora Garment Workers

Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 7 July 2019 The Oppressive Pressures of Globalization and Neoliberalism on Mexican Maquiladora Garment Workers Jenna Demeter The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Business Law, Public Responsibility, and Ethics Commons, Economic History Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Growth and Development Commons, Income Distribution Commons, Industrial Organization Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, International and Comparative Labor Relations Commons, International Economics Commons, International Relations Commons, International Trade Law Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, Labor Economics Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, Law and Economics Commons, Macroeconomics Commons, Political Economy Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Public Economics Commons, Regional Economics Commons, Rural Sociology Commons, Unions Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons Recommended Citation Demeter, Jenna (2019) "The Oppressive Pressures of Globalization and Neoliberalism on Mexican Maquiladora Garment Workers," Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at The University of Tennessee: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/pursuit/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by -

The Cultural Significance of Women's Textile Co Operatives in Guatemala

HECHO A MANO: THE CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF WOMEN’S TEXTILE CO OPERATIVES IN GUATEMALA A* A thesis submitted to the faculty of 'ZQ IB San Francisco State .University M ^ In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Master of Arts In Humanities by Morgan Alex McNees San Francisco, California Summer 2018 Copyright by Morgan Alex McNees 2018 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read Hecho a Mano: The Significance o f Women s Textile Cooperatives in Guatemala by Morgan Alex McNees, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master in Humanities at San Francisco State University. Cristina Ruotolo, Ph.D. Professor of Humanities —^ t y i t u A . to Laura Garci'a-Moreno, Ph.D. Professor of Humanities HECHOAMANO: THE CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE OF WOMEN’S TEXTILE COOPERATIVES IN GUATEMALA Morgan McNees San Francisco, California 2018 After the civil war Mayan women in Guatemala are utilizing their traditional skills, specifically weaving, to rebuild communities and rediscover what it means to be Mayan today. This thesis will explore the impact of the textile market on the social standing of Mayan women and how weaving allows them to be entrepreneurs in their own right. I will also analyze the significance of Mayan textiles as a unifier and symbol of solidarity among the devastated Mayan communities, and the visual narratives depicted in the artwork and their relationship to the preservation of Mayan heritage. This research will focus on several women’s textile cooperatives in Guatemala. -

Elizabeth and Harold Hinds

Elizabeth and Harold Hinds Imholte Hall, University of Minnesota-Morris Imholte Hall, Main Floor Walk-in Display Huichol yarn art. This piece depicts a ceiba tree with a bird. Beside it a man shoots a bow and arrow. Other insect- like forms fly about. These hallucinatory images are traditional for the Huicholes, who used peyote to bring on visions. Originally a traditional art form, yarn paintings became popular as tourist art. This piece was purchased at Tlaquepaque, a town just outside of Guadalajara, in the 1970’s. The story on the back reads: Los Huicholes no conocían el maíz en tiempos antiguos. Una vez un niño se enteró de que había gente allende las montañas “que tienen algo que llaman maíz,” y fue en su busaca. En camino se encontró con un grupo de hombres que le dijeron que (h)iba a comprar maíz y el, confiando, les acompañó. Lo que no sabía es que esa gente eran en realidad hormigas (los insectos en esta ilustración). La Gente Hormiga que ro(b)e todo lo que encuentra. Al llegar la madrugada se despertó. Bajo un gran pino y descubrió que le habían roido (robado) toda la ropa, el cabello e inclusive las cejas, y que solamente le quedaban el arco y las flechas. Oyó que un pájaro se pasaba en un árbol, y le apuntó con una flecha, pues tenía hambre. El pájaro le reveló que era Tatey Kukurú Uimári, Nuestra Madre Paloma Muchacha, la Madre del Maíz. Le dijo que siguiera a su casa, donde le daría maíz. Translation: The Huichol people didn’t know about maize in ancient times. -

Convention United States and Mexico

Convention between the United States and Mexico Equitable Distribution of the Waters of the Rio Grande Signed at Washington, May 21, 1906 Ratification Advised by the Senate, June 26, 1906 Ratified by the President, December 26, 1906 Ratified by Mexico, January 5, 1907 Ratifications Exchanged at Washington, January 16, 1907 Proclaimed, January 16, 1907 [SEAL of the Department of State] By the President of the United States of America A. PROCLAMATION Whereas a Convention between the United States of America and the United States of Mexico, providing for the equitable distribution of the waters of the Rio Grande for irrigation purposes, and to remove all causes of controversy between them in respect thereto, was concluded and signed by their respective Plenipotentiaries at Washington on the twenty-first day of May, one thousand nine hundred and six, the original of which Convention being in the English and Spanish languages, is word for word as follows: The United States of America and the United States of Mexico being desirous to provide for the equitable distribution of the waters of the Rio Grande for irrigation purposes, and to remove all causes of controversy between them in respect thereto, and being moved by considerations of international comity, have resolved to conclude a Convention for these purposes and have named as their Plenipotentiaries: The President of the United States Of America, Elihu Root Secretary of State of the United States; and The President of the United Sates of Mexico, His Excellency Señor Don Joaquin D. Casasus, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the United States Of Mexico at Washington; who, after having exhibited their respective full powers, which were found to be in good and due form, have agreed upon the following articles: Article I. -

Periódico Oficial

PERIÓDICO OFICIAL “TIERRA Y LIBERTAD” ÓRGANO DEL GOBIERNO DEL ESTADO LIBRE Y SOBERANO DE MORELOS Las Leyes y Decretos son obligatorios, por su publicación en este Periódico Director: M. C. Matías Quiroz Medina El Periódico Oficial “Tierra y Libertad” es elaborado en los Talleres de Impresión de la Cuernavaca, Mor., a 15 de junio de 2016 6a. época 5404 Coordinación Estatal de Reinserción Social y la Dirección General de la Industria Penitenciaria del Estado de Morelos. SEGUNDA SECCIÓN Fe de Erratas al Decreto Número Cuatrocientos GOBIERNO DEL ESTADO Cincuenta y Cuatro por el que se adiciona un PODER LEGISLATIVO Capítulo V Bis denominado Suplantación de Acuerdo Parlamentario que autoriza prórroga Identidad y un Artículo 189 bis, todos al Código hasta por treinta (30) días hábiles, a partir del Penal para el Estado de Morelos; mismo que fue vencimiento del término previsto por el artículo 52, publicado en el Periódico Oficial “Tierra y Libertad” de la Ley de Auditoría y Fiscalización para el número 5394, de fecha 04 de mayo del 2016. Estado de Morelos; al Fondo para el Desarrollo y ………………………………Pág. 7 Fortalecimiento Municipal del Estado de Morelos, PODER EJECUTIVO para la entrega de la cuenta pública SECRETARÍA DE LA CONTRALORÍA correspondiente al primer trimestre del ejercicio Acuerdo por el que se establecen los Lineamientos fiscal 2016. ………………………………Pág. 2 para la elaboración e integración de Libros Acuerdo Parlamentario que autoriza prórroga Blancos y de Memorias Documentales. hasta por treinta (30) días hábiles, a partir del ………………………………Pág. 8 vencimiento del término previsto por el artículo 52, ORGANISMOS de la Ley de Auditoría y Fiscalización para el SECRETARÍA DE ECONOMÍA Estado de Morelos; al Sistema de Conservación, FIDEICOMISO EJECUTIVO DEL FONDO DE Agua Potable y Saneamiento del municipio de COMPETITIVIDAD Y PROMOCIÓN DEL Zacatepec, Morelos, para la entrega de la cuenta EMPLEO pública, correspondiente al primer trimestre del Lineamientos para la solicitud, aprobación, ejercicio fiscal 2016.