Scoping the Past to Reach the Future – a Personal Account

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Māori Land and Land Tenure in New Zealand: 150 Years of the Māori Land Court

77 MĀORI LAND AND LAND TENURE IN NEW ZEALAND: 150 YEARS OF THE MĀORI LAND COURT R P Boast* This is a general historical survey of New Zealand's Native/Māori Land Court written for those without a specialist background in Māori land law or New Zealand legal history. The Court was established in its present form in 1865, and is still in operation today as the Māori Land Court. This Court is one of the most important judicial institutions in New Zealand and is the subject of an extensive literature, nearly all of it very critical. There have been many changes to Māori land law in New Zealand since 1865, but the Māori Land Court, responsible for investigating titles, partitioning land blocks, and various other functions (some of which have later been transferred to other bodies) has always been a central part of the Māori land system. The article assesses the extent to which shifts in ideologies relating to land tenure, indigenous cultures, and customary law affected the development of the law in New Zealand. The article concludes with a brief discussion of the current Māori Land Bill, which had as one of its main goals a significant reduction of the powers of the Māori Land Court. Recent political developments in New Zealand, to some extent caused by the government's and the New Zealand Māori Party's support for the 2017 Bill, have meant that the Bill will not be enacted in its 2017 form. Current developments show once again the importance of Māori land issues in New Zealand political life. -

Māori and Aboriginal Women in the Public Eye

MĀORI AND ABORIGINAL WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE REPRESENTING DIFFERENCE, 1950–2000 MĀORI AND ABORIGINAL WOMEN IN THE PUBLIC EYE REPRESENTING DIFFERENCE, 1950–2000 KAREN FOX THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Fox, Karen. Title: Māori and Aboriginal women in the public eye : representing difference, 1950-2000 / Karen Fox. ISBN: 9781921862618 (pbk.) 9781921862625 (ebook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Women, Māori--New Zealand--History. Women, Aboriginal Australian--Australia--History. Women, Māori--New Zealand--Social conditions. Women, Aboriginal Australian--Australia--Social conditions. Indigenous women--New Zealand--Public opinion. Indigenous women--Australia--Public opinion. Women in popular culture--New Zealand. Women in popular culture--Australia. Indigenous peoples in popular culture--New Zealand. Indigenous peoples in popular culture--Australia. Dewey Number: 305.4880099442 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover image: ‘Maori guide Rangi at Whakarewarewa, New Zealand, 1935’, PIC/8725/635 LOC Album 1056/D. National Library of Australia, Canberra. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Abbreviations . ix Illustrations . xi Glossary of Māori Words . xiii Note on Usage . xv Introduction . 1 Chapter One . -

Defending the High Ground

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. i ‘Defending the High Ground’ The transformation of the discipline of history into a senior secondary school subject in the late 20th century: A New Zealand curriculum debate A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Education Massey University (Palmerston North) New Zealand (William) Mark Sheehan 2008 ii One might characterise the curriculum reform … as a sort of tidal wave. Everywhere the waves created turbulence and activity but they only engulfed a few small islands; more substantial landmasses were hardly touched at all [and]…the high ground remained completely untouched. Ivor F. Goodson (1994, 17) iii Abstract This thesis examines the development of the New Zealand secondary school history curriculum in the late 20th century and is a case study of the transformation of an academic discipline into a senior secondary school subject. It is concerned with the nature of state control in the development of the history curriculum at this level as well as the extent to which dominant elites within the history teaching community influenced the process. This thesis provides a historical perspective on recent developments in the history curriculum (2005-2008) and argues New Zealand stands apart from international trends in regards to history education. Internationally, curriculum developers have typically prioritised a narrative of the nation-state but in New Zealand the history teaching community has, by and large, been reluctant to engage with a national past and chosen to prioritise English history. -

Internal Assessment Resource History for Achievement Standard 91002

Exemplar for internal assessment resource History for Achievement Standard 91002 Exemplar for Internal Achievement Standard History Level 1 This exemplar supports assessment against: Achievement Standard 91002 Demonstrate understanding of an historical event, or place, of significance to New Zealanders An annotated exemplar is an extract of student evidence, with a commentary, to explain key aspects of the standard. These will assist teachers to make assessment judgements at the grade boundaries. New Zealand Qualification Authority To support internal assessment from 2014 © NZQA 2014 Exemplar for internal assessment resource History for Achievement Standard 91002 Grade Boundary: Low Excellence For Excellence, the student needs to demonstrate comprehensive understanding of an 1. historical event, or place, of significance to New Zealanders. This involves including a depth and breadth of understanding using extensive supporting evidence, to show links between the event, the people concerned and its significance to New Zealanders. In this student’s evidence about the Maori Land Hikoi of 1975, some comprehensive understanding is demonstrated in comments, such as why the wider Maori community became involved (3) and how and when the prime minister took action against the tent embassy (6). Breadth of understanding is demonstrated in the wide range of matters that are considered (e.g. the social background to the march, the nature of the march, and the description of a good range of ways in which the march was significant to New Zealanders). Extensive supporting evidence is provided regarding the march details (4) and the use of specific numbers (5) (7) (8). To reach Excellence more securely, the student could ensure that: • the relevance of some evidence is better explained (1) (2), or omitted if it is not relevant • the story of the hikoi is covered in a more complete way. -

Peter Feeney and Family Explore the Off-Season Pleasures of the Hokianga

+ Travel View across Hokianga Harbour from Omapere. upe, the Polynesian navigator who discovered New Zealand, parcelled out the rest of the country K but was careful to keep the jewel in the crown, the Hokianga, to himself. Kupe journeyed from the legendary Hawaiki, and hats off to him, because come Friday night the three-and-a-half-hour drive there can feel a trifle daunting to your average work-worn Aucklander. It’s a trip best saved, as my wife and three children did, for a long weekend. The route to get there is via Dargaville, which takes you off the beaten track. From the Brynderwyn turn-off, traffic evaporates and a scenic drive commences through a small towns-and-countryside landscape that reminds me of the New Zealand I grew up in. We set off gamely one Friday morning with Edith Piaf’s “Je ne regrette rien” blaring on the car stereo, our four-year-old’s choice (lest Frankie be accused of a cultural sophistication beyond her years, it must be said that the tune is from the movie Madagascar III). But somewhere around that darn wrong turn near Dargaville, the patience of our one-year-old, Tilly, finally snapped, along with our nerves. By then Piaf’s signature tune, looped for the hundredth time, began to lose some of its shine. Midway through the gut-churning bends of the Waipoua Forest, Tane Mahuta, our tallest tree, appeared just in time for a pit-stop that saved us from internal familial combustion, and provoked six-year-old Arlo’s comment that he’d certainly seen bigger trees, only This Way he couldn’t quite remember where… Our home for the next four days was my sister Margaret’s stately house, where she enjoys multimillion-dollar views over the harbour in return for a laughable (by Auckland standards) rent. -

Wai 2700 the CHIEF HISTORIAN's PRE-CASEBOOK

Wai 2700, #6.2.1 Wai 2700 THE CHIEF HISTORIAN’S PRE-CASEBOOK DISCUSSION PAPER FOR THE MANA WĀHINE INQUIRY Kesaia Walker Principal Research Analyst Waitangi Tribunal Unit July 2020 Author Kesaia Walker is currently a Principal Research Analyst in the Waitangi Tribunal Unit and has completed this paper on delegation and with the advice of the Chief Historian. Kesaia has wide experience of Tribunal inquiries having worked for the Waitangi Tribunal Unit since January 2010. Her commissioned research includes reports for Te Rohe Pōtae (Wai 898) and Porirua ki Manawatū (Wai 2200) district inquiries, and the Military Veterans’ (Wai 2500) and Health Services and Outcomes (Wai 2575) kaupapa inquiries. Acknowledgements Several people provided assistance and support during the preparation of this paper, including Sarsha-Leigh Douglas, Max Nichol, Tui MacDonald and Therese Crocker of the Research Services Team, and Lucy Reid and Jenna-Faith Allan of the Inquiry Facilitation Team. Thanks are also due to Cathy Marr, Chief Historian, for her oversight and review of this paper. 2 Contents Purpose of the Chief Historian’s pre-casebook research discussion paper (‘exploratory scoping report’) .................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 4 The Mana Wāhine Inquiry (Wai 2700) ................................................................................. 7 -

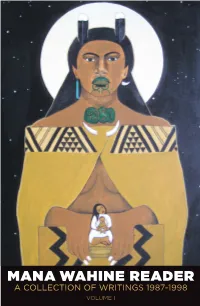

MANA WAHINE READER a COLLECTION of WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader a Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I

MANA WAHINE READER A COLLECTION OF WRITINGS 1987-1998 2 VOLUME I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I I First Published 2019 by Te Kotahi Research Institute Hamilton, Aotearoa/ New Zealand ISBN: 978-0-9941217-6-9 Education Research Monograph 3 © Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Design Te Kotahi Research Institute Cover illustration by Robyn Kahukiwa Print Waikato Print – Gravitas Media The Mana Wahine Publication was supported by: Disclaimer: The editors and publisher gratefully acknowledge the permission granted to reproduce the material within this reader. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information in this book is correct and that articles are as provided in their original publications. To check any details please refer to the original publication. II Mana Wahine Reader | A Collection of Writings 1987-1998, Volume I Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987-1998 Volume I Edited by: Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama and Kirsten Gabel III Table of contents Poem Don’t Mess with the Māori Woman - Linda Tuhiwai Smith 01 Article 01 To Us the Dreamers are Important - Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere 04 Article 02 He Aha Te Mea Nui? - Waerete Norman 13 Article 03 He Whiriwhiri Wahine: Framing Women’s Studies for Aotearoa Ngahuia Te Awekotuku 19 Article 04 Kia Mau, Kia Manawanui -

Level 2 History (91231) 2015

91231R 2 Level 2 History, 2015 91231 Examine sources of an historical event that is of significance to New Zealanders 9.30 a.m. Friday 20 November 2015 Credits: Four RESOURCE BOOKLET Refer to this booklet to answer the questions for History 91231. Check that this booklet has pages 2 – 10 in the correct order and that none of these pages is blank. YOU MAY KEEP THIS BOOKLET AT THE END OF THE EXAMINATION. For copyright reasons, the resources in this booklet cannot be reproduced here. © New Zealand Qualifications Authority, 2015. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced by any means without the prior permission of the New Zealand QualificationsAuthority. 2 THE 1975 MĀORI LAND MARCH INTRODUCTION Early in 1975, representatives of iwi with land grievances attended a hui at Māngere Marae convened by former president of the Māori Women’s Welfare League, Whina Cooper. … After the march, separate groups formed to campaign for the return of the Raglan Golf Course to Māori ownership, and for the return of Bastion Point in Auckland to Ngāti Whātua ownership. Adapted from Ranginui J. Walker ‘Māori People since 1950’ in Geoffrey W. Rice (ed.) The Oxford History of New Zealand, Second Edition (Auckland: Oxford University Press, 1992) pp. 512–513. 3 SOURCE A Source A(i): Māori land loss, 1800–1996 Land in Māori ownership Graeme Ball, Inside New Zealand, Māori–Pakeha Race Relations in the 20th Century (Auckland: New House, 2005), p. 73. Source A(ii): Māori living in cities, 1926–1986 Paul Meredith, ‘Urban Māori – Urbanisation’, Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/graph/3571/maori -urbanisation-1926-86 4 SOURCE B: Whina Cooper and Te Rōpū o te Matakite In 1975, Whina Cooper found herself at the right place at the right time. -

Kura Marie Teira Taylor Te Atiawa Paake Reflections on the Playgrounds of My Life

KURA MARIE TEIRA TAYLOR TE ATIAWA PAAKE REFLECTIONS ON THE PLAYGROUNDS OF MY LIFE Kura Marie Teira Taylor A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Stout Research Centre for New Zealand Studies Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Victoria University of Wellington, 2018 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to: My parents, the late Mouti Erueti Mira Teira Taylor and the late Gracey Nora Skelton Taylor My son Adrian Taylor and wife Susan (nee Darney) My three mokopuna, grandsons: the late Michael Mouti Taylor, B Phys Ed, B Physio (partial), Otago (1 December 1988 – 17 June 2013) Moe moe ra taku mokopuna ataahua John Erueti Taylor, B Sc (Geology), Otago and Anthony Adrian Taylor, Building and Construction, New Plymouth Ma te wa, taku mokopuna, Kia kaha, kia manawanui, kia tau te rangimarie. ii ABSTRACT This thesis is about constructing an indigenous autobiographical narrative of my life as an Aotearoa/New Zealand Te Atiawa Iwi Paake, adult, Maori woman teacher, claiming Maori/Pakeha identity. Three Maori theoretical approaches underpin the thesis: Kaupapa Maori; Mana Wahine, Maori Feminism; and Aitanga. Kaupapa Maori takes for granted being Maori; Maori language, te reo Maori; and tikanga, Maori cultural practices. Whakapapa, Maori descent lines and Pakeha genealogy connect with Maori/Pakeha identity. Mana Wahine, Maori Feminism, is about how Maori women live their lives and view their worlds. Aitanga relates to the distribution of power and Maori as active participants in social relationships. Eight decades of problematic, complex, multi-layered, multi-sited, multi-faceted life experiences of one Maori woman teacher are explored. -

(Canterbury University, NZ) Dip Teaching (Christchurch Secondary Teachers College) Māori Land Protests Hikoi and Bastion Point

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES BLURB: Duration of resource: 27 Minutes The 1970s was a period of great social and political upheaval around the world, including the push for indigenous equality Year of Production: 2013 and land rights. The M āori protest movement was the result of a culmination of grievances dating back to the signing of Stock code: VEA12029 the treaty of Waitangi in 1840. This documentary style program explores: the reasons for the 1970s M āori protest movement; the 1975 Hikoi – protest march; the Occupation of Bastion Point in 1977; and how Aotearoa-New Zealand has changed since the protests. There are interviews with New Zealand historians Claudia Orange, Dr Benjamin Pittman (Great-Great Grandson of Maori Chief Patuone) and Mark Derby. Suitable for New Zealand history, culture related and indigenous rights studies at the senior secondary and further education level, it provides a great overview of the key protests and their enduring significance. Resource written by: Patricia Moore Qualifications B.A. (Canterbury University, NZ) Dip Teaching (Christchurch Secondary Teachers College) Māori Land Protests Hikoi and Bastion Point For Teachers Introduction Māori are Tangata Whenua, the original people of Aotearoa New Zealand. The struggle for their taonga (resources) and tino rangatiratanga (sovereignty) over them began in the early 19 th century. The Hikoi and the Bastion Point protests of the 1970s marked the beginning of the end of that struggle. This program links to the key concept of change. Its aim is to show how change can be effected in societies by direct protest action. It examines the alienation of Māori land in the 19 th and 20 th centuries. -

Black Power and Mana Motuhake." the Black Pacific: Anti-Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections

Shilliam, Robbie. "Black Power and Mana Motuhake." The Black Pacific: Anti-Colonial Struggles and Oceanic Connections. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015. 35–50. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 1 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474218788.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 1 October 2021, 20:29 UTC. Copyright © Robbie Shilliam 2015. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 Black Power and Mana Motuhake Introduction In the decade immediately following the Second World War, the percentage of Māori living in urban areas – as opposed to their mainly rural tūrangawaewae (places of belonging) – rose dramatically from approximately 35 per cent to over 60 per cent. The Hunn report of 1961, written for the Department of Māori Affairs, announced the official thinking on this development. The report recognized that the Māori population, long considered moribund, was now growing and urban- izing at a rate that was outstripping extant infrastructures. At the same time, however, the report actively promoted urbanization by encouraging Crown purchase of Māori land to facilitate development programmes, even while acknowledging that employment for Māori would be a future problem. The report proposed in a distinctly colonial-racial language that the ‘integration’ of Māori into predominantly Pākehā (settler European) urban areas had a modernizing effect on those who were ‘complacently living a backward life in primitive conditions’.1 Complicating but in many ways intensifying this confluence of urbanization, racism and assimi- lation was the migration of Tangata Pasifika (peoples of Oceania) over the same time period. -

Pakanae Koutu Tasman Sea Did You Know: in 1900, the Busy Kauri

To Kaitaia Find more at northlandjourneys.co.nz 10 Journey route Food Scenic views Motukaraka KOHUKOHU Gravel road Cafe Photo stop 13 11 1 12 Car Ferry Point of interest Shop Local favourite Panguru Motuti RAWENE Swimming Petrol station Don’t miss 9 Did you know: In 1900, the busy Kauri milling Rawene Cemetery township of Kohukohu had a NORTHLAND d R population of almost 2,000 people. NZ st e a Mitimiti W st C o r Kaitaia u Rawene 44KM o Omapere 68KM b Waipoua 99KM r Whangarei 14 a Enter and leave buildings H Taheke a and property respectfully, Mitimiti Urupa g Red Gateway n closing doors and gates Auckland a i Te Pouahi – ‘the post k 8 behind you. o Please respect sacred of fire’ is the first H Koutu 12 landing place of the urupā and cemeteries by great Polynesian not eating, drinking or Tasman Sea Kupe explorer Kupe, smoking there, and Pakanae named for the washing your hands way the light when you leave. Journey - Coast to Coast’ Ara of Islands via ‘Te Bay Kaikohe, To strikes the shore. 7 OPONONI & OMAPERE According to Maori mythology, the two Niniwa entrance headlands are 6 Old Wharf Road taniwha named Arai Te Uru (Taniwha) 3 in the south, and Niniwa in 5 Arai Waiotemarama the north, who guard the Te Uru harbour entrance. Reserve Arai Te Uru 15 Km (Taniwha) Waimamaku 4 W a SS Ventnor ip o 28 October 1902 u a All over Aotearoa F o New Zealand, when r e s a tree is felled, t thanks is given to 2 Tāne Mahuta for The Hokianga is known by three names: giving up one of his Tāne Mahuta • Hokianga Whakapau Karakia - ‘Hokianga expend karakia’ children.