Ejagham Bakume2002 O.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ekoid: Bantoid Languages of the Nigeria-Cameroun Borderland

EKOID: BANTOID LANGUAGES OF THE NIGERIA-CAMEROUN BORDERLAND Roger Blench DRAFT ONLY NOT TO BE QUOTED WITHOUT PERMISSION Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. The Ekoid-Mbe languages: Overview ....................................................................................................... 1 2. Classification................................................................................................................................................ 3 2.1 External.................................................................................................................................................. 3 2.2 Internal................................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Phonology..................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. Morphology.................................................................................................................................................. 6 5. Conclusions .................................................................................................................................................. 7 References....................................................................................................................................................... -

![XXXLC..QX...XNX ,Xjxm0.]X...!XX](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8756/xxxlc-qx-xnx-xjxm0-x-xx-1728756.webp)

XXXLC..QX...XNX ,Xjxm0.]X...!XX

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON See over for Abstract of Thesis notes on completion Author (ful] names) Title of thesis ...ID.X.X ihT.X+lfe X H o K ) 0 L O Q 1 ...... XXXLC..QX....XNX ,XjXM0.]X...!XX...^...Lk.X7y^.... ....................................................................... Degree X .U l> .3X tX D U N & l This thesis investigates the forms, functions and behaviour of tone in the phonology, lexicon, morphosyntax and the phonology-grammar interfaces in Ikaan (Benue-Congo, Nigeria). The analysis is based on an annotated audio corpus of recordings from 29 speakers collected during ten months of fieldwork complemented with participant observation and informally collected data. The study demonstrates that tone operates at a wide range of levels of linguistic analysis in Ikaan. As phonemes, tones distinguish meaning in minimal pairs and are subject to phonological rules. As morphemes, tones and tonal melodies bear meaning in inflection, derivation and reduplication. In the syntax, tones mark phrase boundaries. At the phonology-semantics interface, construction-specific constraints on tonal representation distinguish between predicating and referential nominal modifiers. Combined with intonation and voicing, tones distinguish between statements and morphosyntactically identical yes/no questions. The research identifies a range of unusual tonal behaviours in Ikaan. The two tones H and L follow markedly different phonologies. In the association of lexical and grammatical tonal melodies, H must be realised whereas non-associated L are deleted. Formerly associated but de-linked L however are not deleted but remain floating. The OCP is found to apply to L but not to H. H is downstepped after floating L b.ut not after overt L. -

Denya Phonology

DENYA PHONOLOGY by Tanyi Eyong Mbuagbaw Cameroon Bible Translation Association (CABTA) B.P 1299, Yaounde, Cameroon 1996 ABBREVIATIONS AND SYMBOLS [ ] phonetic data / / phonemicised data V vowel cons. consonant cont. continuant sg. singular pl. plural lat. lateral cor. coronal strid. strident nas. nasal ant. anterior U.F. Underlying form DS Downstep H High L Low Del. Rel. Delayed Release N. Syllabic Nasal n. cl Noun class A.M Associative Marker T Tone T Floating Tone # Morpheme boundary 2 SP Soft Palate σ Syllable node R Rhyme O Onset C Coda x Segment V. ass. Vowel Assimilation V. Ct. Vowel Contraction V. El. Vowel Elision NP Noun Phrase VP Verb Phrase DET Determiner SPE Sound Pattern of English 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The data used for the analysis was first collected during the Christmas week of December 1993. More than 2000 words were collected from pastor Ncha Gabriel Bessong and Lucas Ettamambui. The data was corrected and expanded in July 1995 by the above two persons and also by some members of the Denya language committee. They are namely: Daniel Eta Akwo, and Mr. Robinson Tambi. All of them were prepared to give any assistance to see this work completed. I am indeed very grateful to them. I am very grateful to my wife who was always patient with me during the long period devoted to this work especially working long periods at night. I am also very grateful to Dr. Steven Bird and Dr. Jim Roberts for their input in this Phonology. I am very greatful to Dr. Keith Snider whose insight in African languages has helped me to complete this work. -

East Benue-Congo

East Benue-Congo Nouns, pronouns, and verbs Edited by John R. Watters language Niger-Congo Comparative Studies 1 science press Niger-Congo Comparative Studies Chief Editor: Valentin Vydrin (INALCO – LLACAN, CNRS, Paris) Editors: Larry Hyman (University of California, Berkeley), Konstantin Pozdniakov (INALCO – LLACAN, CNRS, Paris), Guillaume Segerer (LLACAN, CNRS, Paris), John Watters (SIL International, Dallas, Texas). In this series: 1. Watters, John R. (ed.). East Benue-Congo: Nouns, pronouns, and verbs. 2. Pozdniakov, Konstantin. The numeral system of Proto-Niger-Congo: A step-by-step reconstruction. East Benue-Congo Nouns, pronouns, and verbs Edited by John R. Watters language science press John R. Watters (ed.). 2018. East Benue-Congo: Nouns, pronouns, and verbs (Niger-Congo Comparative Studies 1). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/190 © 2018, the authors Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-96110-100-9 (Digital) 978-3-96110-101-6 (Hardcover) DOI:10.5281/zenodo.1314306 Source code available from www.github.com/langsci/190 Collaborative reading: paperhive.org/documents/remote?type=langsci&id=190 Cover and concept of design: Ulrike Harbort Typesetting: Sebastian Nordhoff, John R. Watters Illustration: Sebastian Nordhoff Proofreading: Ahmet Bilal Özdemir, Andrew Spencer, Felix Hoberg, Jeroen van de Weijer, Jean Nitzke, Kate Bellamy, Martin Haspelmath, Prisca Jerono, Richard Griscom, Steven Kaye, Sune Gregersen, Fonts: Linux Libertine, Libertinus Math, Arimo, DejaVu Sans Mono Typesetting software:Ǝ X LATEX Language Science Press Unter den Linden 6 10099 Berlin, Germany langsci-press.org Storage and cataloguing done by FU Berlin Contents Preface iii 1 East Benue-Congo John R. -

The Acoustic Correlates of Atr Harmony in Seven- and Nine

THE ACOUSTIC CORRELATES OF ATR HARMONY IN SEVEN- AND NINE- VOWEL AFRICAN LANGUAGES: A PHONETIC INQUIRY INTO PHONOLOGICAL STRUCTURE by COLEEN GRACE ANDERSON STARWALT Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2008 Copyright © by Coleen G. A. Starwalt 2008 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To Dad who told me I could become whatever I set my mind to (May 6, 1927 – April 17, 2008) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Where does one begin to acknowledge those who have walked alongside one on a long and often lonely journey to the completion of a dissertation? My journey begins more than ten years ago while at a “paper writing” workshop in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. I was consulting with Rod Casali on a paper about Ikposo [ATR] harmony when I casually mentioned my desire to do an advanced degree in missiology. Rod in his calm and gentle way asked, “Have you ever considered a Ph.D. in linguistics?” I was stunned, but quickly recoverd with a quip: “Linguistics!? That’s for smart people!” Rod reassured me that I had what it takes to be a linguist. And so I am grateful for those, like Rod, who have seen in me things that I could not see for myself and helped to draw them out. Then the One Who Directs My Steps led me back to the University of Texas at Arlington where I found in David Silva a reflection of the adage “deep calls to deep.” For David, more than anyone else during my time at UTA, has drawn out the deep things and helped me to give them shape and meaning. -

Clarep Journal of English and Linguistics Academic Writing for Africa: the Journal Article 2

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339300631 A case for Nominalised Focus in Yorùbá Article · February 2020 CITATIONS READS 0 293 1 author: Francis Adefabi University of Benin 4 PUBLICATIONS 1 CITATION SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Split-Focus Constructions in Ṣúpárè View project All content following this page was uploaded by Francis Adefabi on 17 February 2020. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336832444 CLAREP JOURNAL OF ENGLISH AND LINGUISTICS ACADEMIC WRITING FOR AFRICA: THE JOURNAL ARTICLE 2 Article · October 2019 CITATIONS READS 0 105 1 author: Mayowa Akinlotan University of Texas at Austin 21 PUBLICATIONS 16 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Noun phrase in New Englishes; the case of Nigerian English View project Corpus approach to the analysis of meaning View project All content following this page was uploaded by Mayowa Akinlotan on 26 October 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. CLAREP JOURNAL OF ENGLISH AND LINGUISTICS C-JEL VOLUME 1, 2019 ACADEMIC WRITING FOR AFRICA: THE JOURNAL ARTICLE 2 CLAREP Journal of English and Linguistics (C-JEL) is a publication of the Centre for Language Research and English Proficiency. CLAREP JOURNAL OF ENGLISH AND LINGUISTICS C-JEL VOLUME 1, 2019 Edited by Alexandra Esimaje and Josef Schmied GALDA VERLAG2019 Clarep Journal of English and Linguistics (C-JEL) is an annual journal of the Cen- tre for Language Research and English Proficiency. -

Sorting out the Position of Bantu Languages in Bantoid

WOCAL 7 7th World Congress of African Linguistics August 20-24, 2012, Buea, Cameroon SORTING OUT THE POSITION OF BANTU LANGUAGES IN BANTOID Rebecca Grollemund, Jean-Marie Hombert Laboratoire Dynamique du Langage, Lyon, France [email protected] [email protected] Williamson & Blench 2000; Schadeberg 2003 Adapted from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bantoid_languages Bantoid languages • « Bantoid » Krause 1895 – Guthrie (1948): « Bantoid » « Semi-Bantu » – Greenberg (1963): « Bantoid » = genetic unit • Classification widely debated: – Williamson (1971) : “Wide Bantu” versus “Narrow Bantu” – Division Northern versus Southern Bantoid (Watters, 1989) • Northern Bantoid (Hedinger, 1989) • Southern Bantoid (Watters and Leroy, 1989) Simplified classification of Bantoid languages Bantoid Northern Hedinger (1989) Southern Watters (1989); Watters and Leroy (1989) Dakoid Mambiloid Fam Tiba Non-Narrow Narrow Bantu Bantu Jarawan Tivoid Beboid Ekoid Grassfields Nyang NW Other South-Bantoid and Bantu languages (1) • New classification of South-Bantoid and Bantu languages • Links between South-Bantoid and Bantu languages (exact delimitation?) – Linguistic frontier between South-Bantoid and Bantu languages? • Relationships between Bantu and other Southern Bantoid groups South-Bantoid and Bantu languages (2) • Focus on North-Western Bantu languages (A and B10-20-30), closer to some Southern Bantoid languages. – Degree of these affinities – Special attention to Mbam-Bubi (A40-60+A31) languages – Special focus on Jarawan languages -

The Diffusion of Cassava in Africa: Lexical and Other Evidence

The diffusion of cassava in Africa: lexical and other evidence Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Ans 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7847-495590 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm This printout: June 13, 2014 Roger Blench Cassava in Africa: the evidence of vernacular names. Circulation draft TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction........................................................................................................................................................i 2. Cassava in the Americas.................................................................................................................................. ii 3. Cassava in the Africa: historical documentation .......................................................................................... ii 4. Cassava in the Africa: linguistic evidence .................................................................................................... iii 4.1 Data sources................................................................................................................................................ iii 4.2 Analysis .......................................................................................................................................................iv I. Mandioka.....................................................................................................................................................v II. Rogo..........................................................................................................................................................vi -

The Bendi Languages

THE BENDI LANGUAGES: MORE LOST BANTU LANGUAGES? 32nd Annual Conference on African Linguistics: Benue-Congo Workshop Berkeley, 26-27th March, 2001 N.B. a shortened version of this paper was submitted to the proceedings of the above workshop but it has never appeared. [DRAFT CIRCULATED FOR COMMENT -NOT FOR CITATION WITHOUT REFERENCE TO THE AUTHOR Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm Cambridge, 22 November, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................................................................1 2. BACKGROUND INFORMATION...........................................................................................................2 2.1 Bendi populations 2 2.2 Data sources on Bendi languages 2 2.3 Transcriptions 3 3. DATASHEETS AND ANALYSES ............................................................................................................3 4. EVALUATING THE COMPETING CLAIMS .....................................................................................22 5. CONCLUSIONS .......................................................................................................................................23 TABLES TABLE 1. THE BENDI LANGUAGES ....................................................................................................................2 -

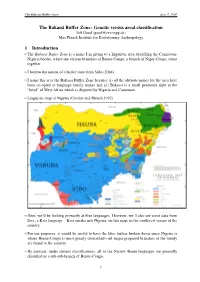

The Bakassi Buffer Zone June 7, 2005

The Bakassi Buffer Zone June 7, 2005 The Bakassi Buffer Zone: Genetic versus areal classification Jeff Good ([email protected]) Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology 1 Introduction [1] The Bakassi Buffer Zone is a name I’m giving to a linguistic area straddling the Cameroon- Nigeria border, where the various branches of Benue-Congo, a branch of Niger-Congo, come together. [2] I borrow the notion of a buffer zone from Stilo (2004). [3] I name this area the Bakassi Buffer Zone because (i) all the obvious names for the area have been co-opted as language family names and (ii) Bakassi is a small peninsula right at the “bend” of West Africa which is disputed by Nigeria and Cameroon. [4] Linguistic map of Nigeria (Crozier and Blench 1992) [5] Here, we’ll be looking primarily at blue languages. However, we’ll also see some data from Ewe, a Kwa language—Kwa sneaks into Nigeria, on this map, in the southwest corner of the country. [6] For our purposes, it would be useful to have the blue further broken down since Nigeria is where Benue-Congo is most greatly diversified—all major proposed branches of the family are found in the country. [7] By contrast, under current classifications, all of the Narrow Bantu languages are generally classified as a sub-sub-branch of Benue-Congo. 1 The Bakassi Buffer Zone June 7, 2005 [8] Linguistic map of Cameroon (Dieu and Renaud 1983:369) [9] Cameroon shows considerably less diversity than Nigeria in terms of containing different branches of Niger-Congo. -

The Ukaan Language

THE UKAAN LANGUAGE: BANTU IN SOUTH-WESTERN NIGERIA? Revised Version of Paper given at the Hamburg Conference ‘Trends in the Historical Study of African Languages’ Hamburg 3-7th September, 1994 Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://homepage.ntlworld.com/roger_blench/RBOP.htm Printed out: December 8, 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction.................................................................................................................................................... 1 2. Phonology and Noun-class pairings ............................................................................................................. 1 3. Comparative Ukaan wordlist........................................................................................................................ 2 4. The Classification of Ukaan.......................................................................................................................... 8 1. Introduction The Ukaan languages, are spoken around Auga and Kakumo, directly south of Kabba near the Niger-Benue Confluence in Nigeria (Map 1). Ukaan has until recently been known only from a wordlist given in Jungraithmayr (1973). However, two unpublished papers give substantially more lexicon and some morphological information (Abiodun, 1989 and Ohiri-Aniche 1999). This paper1 presents some of this lexical data together with an analysis of the possible sources and -

The Bantoid Languages

THE BANTOID LANGUAGES Roger Blench DRAFT ONLY NOT TO BE QUOTED WITHOUT PERMISSION Roger Blench Kay Williamson Educational Foundation 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/ Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 Mobile worldwide (00-44)-(0)7967-696804 E-mail [email protected] http://www.rogerblench.info/RBOP.htm The Bantoid languages: a monograph Draft not for circulation. Front matter TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................................... 1 2. THEORIES AND METHODS................................................................................................................... 1 2.1 Lexicostatistics and other mathematical methods ..............................................................................................1 2.2 Shared innovations ................................................................................................................................................2 2.3 Historical reconstruction.......................................................................................................................................3 3. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW...................................................................................................................... 3 4. [EAST] BENUE-CONGO........................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Overview.................................................................................................................................................................8