The Story of the Stars & Stripes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE EAST LOTHIAN FLAG COMPETITION the Recent

THE EAST LOTHIAN FLAG COMPETITION The recent competition held to select a flag for the county of East Lothian, elicited four finalists; three of these were widely criticised for falling short of good design practice, as promoted for several years, by such bodies as the North American Vexillological Association and the Flag Institute. The latter’s Creating Local & Community Flags guide , as recently advertised by the Flag Institute's official Twitter feed on Monday 8th October 2018, states on page 7, that "Designs making it to the shortlist of finalists must meet Flag Institute design guidelines to ensure that all potential winning designs are capable of being registered." and further notes that "Flags are intended to perform a specific, important function. In order to do this there are basic design standards which need to be met." Page 8 of the same guide, also declares, "Before registering a new flag on the UK Flag Registry the Flag Institute will ensure that a flag design: Meets basic graphical standards." This critique demonstrates how the three flags examined, do not meet many of the basic design standards and therefore do not perform the specific and important intended functions. As a result, on its own grounds, none of the three can be registered by the Flag Institute. Flag B Aside from the shortcomings of its design, Flag B fails to meet the Flag Institute's basic requirement that any county flag placed on the UK Flag Registry cannot represent a modern administrative area. The Flag Institute’s previously cited, community flag guide, describes on page 6, the categories of flags that may be registered; "There are three types of flag that might qualify for inclusion in the UK Flag Registry: local community flags (including cities, towns and villages), historic county flags and flags for other types of traditional areas, such as islands or provinces. -

![Scotland [ˈskɑtlənd] (Help·Info) (Gaelic: Alba) Is a Country In](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4036/scotland-sk-tl-nd-help%C2%B7info-gaelic-alba-is-a-country-in-414036.webp)

Scotland [ˈskɑtlənd] (Help·Info) (Gaelic: Alba) Is a Country In

SCOTLAND The national flag of Scotland, known as the Saltire or St. Andrew's Cross, dates (at least in legend) from the 9th century, and is thus the oldest national flag still in use. St Andrew's Day, 30 November, is the national day, although Burns' Night tends to be more widely observed. Tartan Day is a recent innovation from Canada. Scotland is a country in northwest Europe that occupies the northern third of the island of Great Britain. It is part of the United Kingdom, and shares a land border to the south with England. It is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the southwest. In addition to the mainland, Scotland consists of over 790 islands including the Northern Isles and the Hebrides. Scotland contains the most mountainous terrain in Great Britain. Located at the western end of the Grampian Mountains, at an altitude of 1344 m, Ben Nevis is the highest mountain in Scotland and Great Britain. The longest river in Scotland is River Tay, which is 193 km long and the largest lake is Loch Lomond (71.1 km2). However, the most famous lake is Loch Ness, a large, deep, freshwater loch in the Scottish Highlands extending for approximately 37 km southwest of Inverness. Loch Ness is best known for the alleged sightings of the legendary Loch Ness Monster, also known as "Nessie". One of the most iconic images of Nessie is known as the 'Surgeon's Photograph', which many formerly considered to be good evidence of the monster. -

The Colours of the Fleet

THE COLOURS OF THE FLEET TCOF BRITISH & BRITISH DERIVED ENSIGNS ~ THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE WORLDWIDE LIST OF ALL FLAGS AND ENSIGNS, PAST AND PRESENT, WHICH BEAR THE UNION FLAG IN THE CANTON “Build up the highway clear it of stones lift up an ensign over the peoples” Isaiah 62 vv 10 Created and compiled by Malcolm Farrow OBE President of the Flag Institute Edited and updated by David Prothero 15 January 2015 © 1 CONTENTS Chapter 1 Page 3 Introduction Page 5 Definition of an Ensign Page 6 The Development of Modern Ensigns Page 10 Union Flags, Flagstaffs and Crowns Page 13 A Brief Summary Page 13 Reference Sources Page 14 Chronology Page 17 Numerical Summary of Ensigns Chapter 2 British Ensigns and Related Flags in Current Use Page 18 White Ensigns Page 25 Blue Ensigns Page 37 Red Ensigns Page 42 Sky Blue Ensigns Page 43 Ensigns of Other Colours Page 45 Old Flags in Current Use Chapter 3 Special Ensigns of Yacht Clubs and Sailing Associations Page 48 Introduction Page 50 Current Page 62 Obsolete Chapter 4 Obsolete Ensigns and Related Flags Page 68 British Isles Page 81 Commonwealth and Empire Page 112 Unidentified Flags Page 112 Hypothetical Flags Chapter 5 Exclusions. Page 114 Flags similar to Ensigns and Unofficial Ensigns Chapter 6 Proclamations Page 121 A Proclamation Amending Proclamation dated 1st January 1801 declaring what Ensign or Colours shall be borne at sea by Merchant Ships. Page 122 Proclamation dated January 1, 1801 declaring what ensign or colours shall be borne at sea by merchant ships. 2 CHAPTER 1 Introduction The Colours of The Fleet 2013 attempts to fill a gap in the constitutional and historic records of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth by seeking to list all British and British derived ensigns which have ever existed. -

Colonial Flags 1775-1781

THE AMERICAN FLAG IS BORN American Heritage Information Library and Museum about A Revolutionary Experience GRAND UNION BETSY ROSS The first flag of the colonists to have any During the Revolutionary War, several patriots made resemblance to the present Stars and Stripes. It was flags for our new Nation. Among them were Cornelia first flown by ships of the Colonial Fleet on the Bridges, Elizabeth (Betsy) Ross, and Rebecca Young, all Delaware River. On December 3, 1775 it was raised of Pennsylvania, and John Shaw of Annapolis, Maryland. aboard Capt. Esek Hopkin's flagship Alfred by John Although Betsy Ross, the best known of these persons, Paul Jones, then a navy lieutenant. Later the flag was made flags for 50 years, there is no proof that she raised on the liberty pole at Prospect Hill, which was made the first Stars and Stripes. It is known she made near George Washington's headquarters in flags for the Pennsylvania Navy in 1777. The flag Cambridge, MA. It was the unofficial national flag on popularly known as the "Betsy Ross Flag", which July 4, 1776, Independence Day; and it remained the arranged the stars in a circle, did not appear until the unofficial national flag and ensign of the Navy until early 1790's. June 14, 1777 when the Continental Congress Provided as a Public Service authorized the Stars and Stripes. for over 115 Years COLONIAL THIRD MOUNTAIN REGIMENT The necessity of a common national flag had not been thought of until the appointment of a committee composed of Benjamin Franklin, Messrs. -

Saint Andrew's Society of San Francisco

Incoming 2nd VP Welcome Message By Alex Sinclair ince being welcomed to the St. Andrew’s community almost Stwo years ago, I have been filled with the warmth and joy that this society and its members bring to the San Francisco Bay Area. From dance, music, poetry, history, charity, and edu- cation the charity’s past 155 years has celebrated Scottish cul- ture in its contributions to the people of California. I have been grateful to the many friendly faces and experiences I have had since rediscovering the Scottish identity while at the society. I appreciate everyone who has supported my nomination as an officer within the organisation, and I will try my best no matter Francesca McCrossan, President your vote to support your needs as members and of the success November 2020 of the charity at large. President’s Message Being an officer at the society tends to need a wide range of skills and challenges to meet the needs of the membership and Dear St. Andrew’s Society, the various programs and events we run through the year, in the Looking towards the New Year time of Covid even more so. In my past, I have been a chef, a musician, a filmmaker, a tour manager, a marketeer, an entre- t the last November Members meeting, I was reelected as preneur, an archivist and a specialist in media licencing and Ayour President, and I thank the Members for the honor to digital asset management. I hold an NVQ in Hospitality and Ca- be able to serve the Society for another year. -

11-20 November Issue

The British Isles Historic Society Heritage, History, Traditions & Customs 11-20 November Issue St. Andrew deeming himself unworthy to be crucified in the same manner as Jesus Christ. Instead, he was nailed St. Andrew has been celebrated upon an X-shaped cross on 30 November 60AD in in Scotland for over a thousand years, Greece, and thus the diagonal cross of the saltire with feasts being held in his honour as was adopted as his symbol, and the last day in far back as the year 1000 AD. November designated his saint day. However, it wasn’t until 1320, According to legend, Óengus II, king of Picts when Scotland’s independence was and Scots, led an army against the Angles, a declared with the signing of The Germanic people that invaded Britain. The Scots Declaration of Arbroath, that he officially became were heavily outnumbered, and Óengus prayed the Scotland’s patron saint. Since then St Andrew has night before battle, vowing to name St. Andrew the become tied up in so much of Scotland. The flag of patron saint of Scotland if they won. Scotland, the St. Andrew’s Cross, was chosen in honour of him. Also, the ancient town of St Andrews On the day of the battle, white clouds formed was named due to its claim of being the final resting an X in the sky. The clouds were thought to place of St. Andrew. represent the X-shaped cross where St. Andrew was crucified. The troops were inspired by the apparent According to Christian teachings, Saint Andrew divine intervention, and they came out victorious was one of Jesus Christ’s twelve disciples. -

Webb Horn-Flag Origins

2015 FIELD OF STAR’S & THE ORDER OF THE KNIGHTS GARTER GARY GIANOTTI STAR’S & STRIPES-ORIGNS-REDISCOVERD THE HISTORIANS, MADE NO MENTION OF THE THE SEVEN STRIPES AND GAVE NO INFORMATION OF THE UNION JACK, SHORT FOR JACOBUS OR JAMES VI. Webb Flag Image, Symbolizes the Stars of the Order’s of The Knight’s Garter and Thistle. Blue underlined words are hyper links to documents, images & web sites-Read the The Barnabas Webb carved powder image to be the earliest known Adam’s, Thomas Jefferson and Ben horn made the news in 2012. Carved by depiction of the stars & stripes flag Franklin. This Webbs wife was a Franklin a skilled, Bostonian silversmith. flown in American history. niece, apprentice to her father William The horn carving, depicting the 1776 American Vexillologist’s and historians Homes. Home’s father married Mary siege of Boston, shows the city and a were very quick to dismiss Mr. Millar’s Franklin the sister of Benjamin Franklin, few flags that were flown by the theory. Saying this Stars & stripes who was on the flag design committee American Patriots. During the outbreak predates the Flag Act design by 14 for the Stars & Stripes. The link below of the American War of Independence. months. When Congress members mentions a Mr. Harkins, note him. Historical researcher, John Millar was passed the description of the new Harkins was my close friend, where I the first to notice and document an national flag design called the “Flag Act” advanced the history of his horn and important flag design found on the of June 14th 1777. -

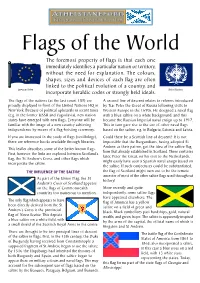

Flags of the World

ATHELSTANEFORD A SOME WELL KNOWN FLAGS Birthplace of Scotland’s Flag The name Japan means “The Land Canada, prior to 1965 used the of the Rising Sun” and this is British Red Ensign with the represented in the flag. The redness Canadian arms, though this was of the disc denotes passion and unpopular with the French sincerity and the whiteness Canadians. The country’s new flag represents honesty and purity. breaks all previous links. The maple leaf is the Another of the most famous flags Flags of the World traditional emblem of Canada, the white represents in the world is the flag of France, The foremost property of flags is that each one the vast snowy areas in the north, and the two red stripes which dates back to the represent the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. immediately identifies a particular nation or territory, revolution of 1789. The tricolour, The flag of the United States of America, the ‘Stars and comprising three vertical stripes, without the need for explanation. The colours, Stripes’, is one of the most recognisable flags is said to represent liberty, shapes, sizes and devices of each flag are often in the world. It was first adopted in 1777 equality and fraternity - the basis of the republican ideal. linked to the political evolution of a country, and during the War of Independence. The flag of Germany, as with many European Union United Nations The stars on the blue canton incorporate heraldic codes or strongly held ideals. European flags, is based on three represent the 50 states, and the horizontal stripes. -

Historic Flag Presentation

National Sojourners, Incorporated Historic Flag Presentation 16 July 2017 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 Type of Program 4 Program Description and Background Information 4 Origin of a Historic Flag Presentation 4 What is a Historic Flag Presentation? 4 Intended Audience of a Historic Flag Presentation 4 Number required to present a Historic Flag Presentation 5 Presentation Attire 5 List of Props Needed and Where Can Props Be Obtained 5 List of Support Equipment (computer, projector, screen, etc.) 5 Special Information 5 Script for an Historic Flag Presentation 6-20 Purpose 6 General Flag Overview 6 Bedford Flag—April 1775 6 Rhode Island Regiment Flag—May 1775 8 Bunker Hill Flag—June 1775 8 Washington’s Cruisers Flag—October 1775 8 Gadsden Flag—December 1775 8 Grand Union Flag—January 1776 9 First Navy Jack—January 1776 9 First Continental Regiment Flag—March 1776 9 Betsy Ross Flag—May 1776 9 Moultrie Flag—June 1776 9 Independence Day History 9 13-Star Flag—June 1777 10 Bennington Flag—August 1777 10 Battle of Yorktown 10 Articles of Confederation 10 15-Star Flag (Star-Spangled Banner)—May 18951 11 20-Star Flag—April 1818 11 Third Republic of Texas Flag—1839-1845 11 Confederate Flag—1861-1865 12 The Pledge to the Flag 11 1909 12 48-Star Flag—September 1912-1959 13 2 World War I 12 Between the Wars 13 World War II 13 Battle of Iwo Jima 13 End of World War II 13 Flag Day 14 Korean War 14 50-Star Flag—July 1960-Present 14 Toast to the Flag 15 Old Glory Speaks 16 That Ragged Old Flag 17 3 Type of Program The Historic Flag Presentation is both a patriotic and an educational program depending on the audience. -

Civic Center Plaza Flagpoles Historical Background

Civic Center Plaza Flagpoles Historical Background Preceeding Events The flagpoles were installed during a period of great nationalism, especially in San Francisco. The Charter of the United Nations was signed in 1945 in the War Memorial Hall Building (Herbst Theatre); while the War Memorial Opera House, and other local venues were host to the two-month-long gathering of global unity. There were some 3500 delegation attendees from 50 nations, and more than 2500 press, radio and newsreel representatives also in attendance. (United Nations Plaza was dedicated later, in 1975, on the east side of the plaza as the symbolic leagcy of that event.) World War II was still in the minds of many, but a more recent event was the statehood of both Alaska and Hawaii during 1959, which brought thoughts of the newly designed flag to the fore, especially to school children who saluted the flag each morning. With two new stars, it looked different. And finally, John F. Kennedy was elected preident in November 1960; he was the youngest president ever elected bringing a new optimism and energy to the country. The Pavilion of American Flags Although all of the flagpoles seen today were in the original design, there does not seem to have been a specific theme for what the many staffs would display. The central two parallel rows containing a total of 18 flagpoles, known as The Pavilion of American Flags, flank the east-facing view of the Civic Center Plaza from the mayor’s office. An idea was presented that would feature flags which played an important role in the nation’s history. -

Info-FIAV 37

Info-FIAV No. 37, July 2015 ISSN 1560-9979 Fédération internationale des associations vexillologiques Federación Internacional de Asociaciones Vexilológicas International Federation of Vexillological Associations Internationale Föderation Vexillologischer Gesellschaften www.fiav.org TWENTY-FOURTH SESSION OF THE FIAV GENERAL ASSEMBLY SEPTEMBER 1, 2015 Every FIAV Member is strongly encouraged to appoint a delegate and alternate to represent it at the Twenty-Fourth Session of the FIAV General Assembly on September 1, 2015. If no person from a FIAV Member is able to come to the General Assembly Session, that FIAV Member is strongly encouraged to appoint as its delegate either the delegate of another FIAV Member or one of the three FIAV Officers. This will be the third General Assembly session to which current article 8 of the FIAV Constitution applies. Credentials should be brought to the General Assembly Session. If at all possible, credentials should be on the Member’s official stationery. The suggested form of written credentials is as follows: To the President of the Fédération internationale des associations vexillologiques: [Name of FIAV Member association or institution] appoints [name of person (and alternate, if desired)], as its delegate to the Twenty-Fourth Session of the FIAV General Assembly, to be convened September 1, 2015, in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. [Delegate’s name] has full powers to act on behalf of [name of FIAV Member association or institution] during the Twenty-Fourth Session of the General Assembly [or] The powers of [delegate’s name] to act on behalf of [name of FIAV Member association or institution] during the Twenty-Fourth Session of the General Assembly are limited as follows: [describe]. -

The Union Flag and Flags of the United Kingdom

BRIEFING PAPER Number 04474, 1 June 2021 Flags: the Union Flag and By Hazel Armstrong flags of the United Kingdom Contents: 1. Background 2. National flags of the UK 3. Northern Ireland www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 Flags: the Union Flag and flags of the United Kingdom Contents Summary 3 1. Background 4 1.1 Flag flying on royal residences 5 1.2 Flag flying on Government Buildings 6 1.3 European Flag 9 1.4 Flag flying at UK Parliament 9 1.5 Guidance for local authorities, individuals and organisations 11 2. National flags of the UK 13 2.1 The United Kingdom 13 2.2 England 15 2.3 Scotland 16 2.4 Wales 18 3. Northern Ireland 22 3.1 Historical flags 22 3.2 1954 Act 22 3.3 Government Buildings in Northern Ireland 23 3.4 Northern Ireland Assembly 26 3.5 Belfast City Council 26 3.6 Commission on Flags, Identity, Culture and Tradition (FICT) 27 Attribution: Union Jack with building by andrewbecks / image cropped. Licensed under Pixabay License – no copyright required. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 1 June 2021 Summary Union flag or Union jack? The Union Flag, commonly known as the Union Jack, is the national flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. The original Union Flag was introduced in 1606 as a maritime flag and in 1634, a Royal Proclamation laid down that the Union Flag was reserved for His Majesty’s Ships of War. When the 'Union Jack' was first introduced in 1606, it was known simply as 'the British flag' or 'the flag of Britain'.