Media Contingency in the 1930S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art for Everyone

COLOR Healing with Flower Essences PLUS Art for Everyone $5.00 ISSUE 88 VOL. 22, Summer 2017 Soil, Culture & Human Responsibility • Truth & Lies Android App On Editor’ s note dear readers Welcome to our summer issue that’s and shared some cheese and fruit and crackers before filled with plenty of art and color to reading the last chapter in the book we have been lift your spirits. Many would agree studying, Rudolf Steiner’s lectures on honey bees. that we are in uncertain times, so Gathering with people around a common aspiration more than ever, we need to be there is another remedy that renews my sense of purpose for each other, but we also need to and direction. be there for ourselves too. Speaking of remedies! We are bringing back our I can’t be prescriptive, but I can share a couple of Holistic Wellness Guide (see page 6) this fall. If you recent experiences that have helped me stay grounded are a subscriber, you will receive this as your Fall and optimistic. I grow a lot of flowers, and each day issue. A team of anthroposophic doctors and nurses I spend time with them. I enjoy their colors and the helped us do a thorough edit of the ever-so-useful A-Z bird and insect life they attract. Our daughter gave us Guide of common ailments and home health-based a wildflower seed packet last year, and from that we solutions. New articles on public health, vaccinations, have many volunteer poppies that grew up red and anthroposophic nursing, and osteopathy will be side pink and tall. -

Chanticleer May & June 2015

NEWSLETTER OF THE BERKSHIRE-TACONIC BRANCH OF THE ANTHROPOSOPHICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 25, ISSUE 9, MAY/JUNE 2015 Where the Bee sucks, there suck I. In a cowslip’s bell I lie; There I couch when owls do cry. On the bat’s back I do fly After summer merrily. Merrily, merrily shall I live now Under the blossom that hangs on the bough. (ARIEL’s final song in The Tempest by William Shakespeare, Act 5, Scene 1, lines 88-94) Drawing; E. Lapointe Pentecost ur Christian festival of Pentecost is related in a beautiful way to what is above the stars: the universal “Ospiritual fire of the cosmos, individualised and descending in fiery tongues upon the Apostles. This fire is neither of the heavens nor of the earth, neither cosmic nor merely terrestrial, but permeates every- thing, yet it is individualised and reaches every human being. Pentecost is connected with the whole world! Just as the Christmas festival is connected with the earth and the Easter festival with the stars, so Pentecost is directly connected with every human being when he or she receives the spark of spiritual life out of the whole universe. What all humanity received in the descent of the divine human being to earth is given to each individual in the fiery tongues of Pentecost. The fiery tongues represent what is in us, in the universe, and in the stars. Thus, especially for those who seek the spirit, Pentecost has a special, profound meaning, summoning us again and again to seek anew for the spirit.” Rudolf Steiner, lecture given 99 years ago at Pentecost in Berlin, June 6, 1916 (GA 169). -

I Go W Where G I Lo Love

EANAEANA I gog wwhere I lollove..... EurythmyEuryythmy ~ Christtina Beck Speeech/Acting ~ BBeatrice Vo Mussic ~ Several coollaboratin Performances/Workshops Begin Fall 2018 Sponsored by Lemniscate Arts Tax deductible donations may be made to: Lemniscate Arts a 501(c)3 corporationtion (#20-2307129) noted for Amaranthth Eurythmy Theater and sent to 114 Tuscarora Dr.,, Hillsborough, NC 27278 or online at amarantheurythmytheater.orgntheurythmytheater.org Contact: [email protected] AMMARANTTH EURYYTTHMY TTHEEAATTER VOLUME 95 Spring 2018 OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE EURYTHMY ASSOCIATION OF NORTH AMERICA NEWSLETTERNEWSLETTER 2 Eurythmy Association of North America Mission Statement The Eurythmy Association of North America is formed for these purposes: To foster eurythmy, an art of movement originated and developed by Rudolf Steiner out of anthroposophy; to foster the work of eurythmists on the North American continent by sponsoring performances, demonstrations, and workshops; and to main- tain, develop, and communicate knowledge related to eurythmy and the work of eurythmists by means of newsletters and publications. The Eurythmy Association of North America is a non- OFFICERS OF THE EURYTHMY ASSOCIATION profit corporation of eurythmists living and working on the President Emeritus North American continent. Any eurythmist holding an Alice Stamm, 916-728-2462 accredited diploma recognized by the Section for Eurythmy, Treasurer Speech, and Music at the Goetheanum, may join the Gino Ver Eecke, 845-356-1380 Association as a member. Eurythmy students and non- Corresponding Secretary accredited, but actively working eurythmists, are warmly Alice Stamm, 916-728-2462 welcomed to join as Friends. Recording Secretary The Newsletter is published two times annually. Laurel Loughran, 778-508-3554 Annual dues are from January through December. -

(Iowa City, Iowa), 1948-02-14

lbCal - Team to Indiana; Lincoln. Train ~ THE WEATHER TODAY Cold wave to day and tonight. Snow flurries and strong shifting winds today diminishing to Hawks Invade Indiana night. Tomorrow partly cloudy and quite cold . High near 30. Low zero to 5 below. low yester .In rry for Loop Top at owa11. day in Iowa City, 14. By BUCK TURNBULL .. .. F.tabliahed 18GS-Vol 80, No. 118-AP News and Wirephoto Iowa Clty, Iowa, Saturday, rebruary 14, 1948-Five Cents ports Edltor . BLOOMINGTON, Ind. (JP) The Lincoln Train 4. Indiana basketball learn stands between Iowa and lhe Big Nine Small Boy - But· a Big Operator leaderShip as the two learns Senate Group Agrees ~uare off here in the Hoosier Slops In Ie lieldhouse tonigh L 'l'he Hawkeye quintet, riding the crest of thl'ee straight confer enl'l! wins nnd a six won-two lost Enroule Easl European Bill league record, can move ahead of On Aid Wisconsin's idle Badgers with a. The Rock Island section of the "Iclory over l ndians. Wisconsin Abraham Lincoln Friendship train WASHINGTON (IP)-Aid to and Iowa are currently tied for pulled into Iowa City at 7:37 yes * * * Europe received a shot in the arm the Big Nine top. terday morning, paused briefly for yesterday. Late in the afternoon the press and co ntinued on Its The Hawks c'.~ealed Indiana Upholds Union a Senate foreign relations commit mission. earlier III the season al Iowa City, Twenty-eight cars of wheat and , tee agreed on a four-year Europe 61 -52. an recovery program. -

Lacon 1 Film Program

BY WAY OF INTRODUCTION This film program represents for the most part an extremely personal selection by me, Bill Warren, with the help of Donald F. Glut. Usually convention film programs tend to show the established classics -- THINGS TO COME, METROPOLIS, WAR OF THE WORLDS, THEM - and, of course, those are good films. But they are seen so very often -- on tv, at non-sf film programs, at regional cons, and so forth -- that we decided to try to organize a program of good and/or entertaining movies that are rarely seen. We feel we have made a good selection, with films chosen for a variety of reasons. Some of the films on the program were, until quite recently, thought to be missing or impossible to view, like JUST IMAGINE, TRANSATLANTIC TUNNEL, or DR JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE. Others, since they are such glorious stinkers, have been relegated to 3 a.m. once-a-year tv showings, like VOODOO MAN or PLAN 9 FROM OUTER SPACE. Other fairly recent movies (and good ones, at that) were, we felt, seen by far too few people, either due to poor distribution by the releasing companies, or because they didn't make enough money to ensure a wide release, like TARGETS or THE DEVIL'S BRIDE. Still others are relatively obscure foreign films, a couple of which we took a sight-unseen gamble on, basing our selections on favorable reviews; this includes films like THE GLADIATORS and END OF AUGUST AT THE HOTEL OZONE. And finally, there are a number of films here which are personal favorites of Don's or mine which we want other people to like; this includes INTERNATIONAL HOUSE, MAD LOVE, NIGHT OF THE HUNTER, RADIO RANCH, and SPY SMASHER RETURNS. -

The Picture Show Annual (1928)

Hid •v Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/pictureshowannuaOOamal Corinne Griffith, " The Lady in Ermine," proves a shawl and a fan are just as becoming. Corinne is one of the long-established stars whose popularity shows no signs of declining and beauty no signs of fading. - Picture Show Annual 9 rkey Ktpt~ thcMouies Francis X. Bushman as Messala, the villain of the piece, and Ramon Novarro, the hero, in " Ben Hut." PICTURESQUE PERSONALITIES OF THE PICTURES—PAST AND PRESENT ALTHOUGH the cinema as we know it now—and by that I mean plays made by moving pictures—is only about eighteen years old (for it was in the Wallace spring of 1908 that D. W. Griffith started to direct for Reid, the old Biograph), its short history is packed with whose death romance and tragedy. robbed the screen ofa boyish charm Picture plays there had been before Griffith came on and breezy cheer the scene. The first movie that could really be called iness that have a picture play was " The Soldier's Courtship," made by never been replaced. an Englishman, Robert W. Paul, on the roof of the Alhambra Theatre in 18% ; but it was in the Biograph Studio that the real start was made with the film play. Here Mary Pickford started her screen career, to be followed later by Lillian and Dorothy Gish, and the three Talmadge sisters. Natalie Talmadge did not take as kindly to film acting as did her sisters, and when Norma and Constance had made a name and the family had gone from New York to Hollywood Natalie went into the business side of the films and held some big positions before she retired on her marriage with Buster Keaton. -

RUDOLPH VALENTINO January 1971

-,- -- - OF THE SON SHEIK . --· -- December 1970 -.. , (1926) starring • January 1971 RUDOLPH VALENTINO ... r w ith Vilma Banky, Agnes Ayres, George Fawcett, Kar l Dane • .. • • i 1--...- \1 0 -/1/, , <;1,,,,,/ u/ ~m 11, .. 12/IOJ,1/, 2/11.<. $41 !!X 'ifjl!/1/. , .....- ,,,1.-1' 1 .' ,, ,t / /11 , , . ... S',7.98 ,,20 /1/ ,. Jl',1,11. Ir 111, 2400-_t,' (, 7 //,s • $/1,!!.!!8 "World's .. , . largest selection of things to show" THE ~ EASTIN-PHELAN p, "" CORPORATION I ... .. See paee 7 for territ orial li m1la· 1;on·son Hal Roach Productions. DAVE PORT IOWA 52808 • £ CHAZY HOUSE (,_l928l_, SPOOK Sl'OO.FI:'\G <192 i ) Jean ( n ghf side of the t r acks) ,nvites t he Farina, Joe, Wheeze, and 1! 1 the Gang have a "Gang•: ( wrong side of the tr ack•) l o a party comedy here that 1\ ,deal for HallOWK'n being at her house. 6VI the Gang d~sn't know that a story of gr aveyard~ - c. nd a thriller-diller Papa has f tx cd the house for an April Fool's for all t ·me!t ~ Day party for his fr i ends. S 2~• ~·ar da,c 8rr,-- version, 400 -f eet on 2 • 810 303, Standord Smmt yers or J OO feet ? O 2 , v ozs • Reuulart, s11.9e, Sale reels, 14 ozs, Regularly S1 2 98 , Sale Pnce Sl0.99 , 6o 0 '11 Super 8 vrrs•OQ, dSO -fect,, 2-lb~ .• S l0.99 Regu a rly SlJ 98. Sale Pn ce I Sl2.99 425 -fect I :, Regularly" ~ - t S12 99 400lc0 t on 8 o 289 Standard 8mm ver<lon SO r Sate r eels lJ o,s-. -

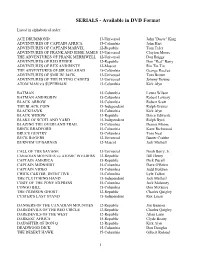

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format Listed in alphabetical order: ACE DRUMMOND 13-Universal John "Dusty" King ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN AFRICA 15-Columbia John Hart ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL 12-Republic Tom Tyler ADVENTURES OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES 13-Universal Clayton Moore THE ADVENTURES OF FRANK MERRIWELL 12-Universal Don Briggs ADVENTURES OF RED RYDER 12-Republic Don "Red" Barry ADVENTURES OF REX AND RINTY 12-Mascot Rin Tin Tin THE ADVENTURES OF SIR GALAHAD 15-Columbia George Reeves ADVENTURES OF SMILIN' JACK 13-Universal Tom Brown ADVENTURES OF THE FLYING CADETS 13-Universal Johnny Downs ATOM MAN v/s SUPERMAN 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BATMAN 15-Columbia Lewis Wilson BATMAN AND ROBIN 15-Columbia Robert Lowery BLACK ARROW 15-Columbia Robert Scott THE BLACK COIN 15-Independent Ralph Graves BLACKHAWK 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BLACK WIDOW 13-Republic Bruce Edwards BLAKE OF SCOTLAND YARD 15-Independent Ralph Byrd BLAZING THE OVERLAND TRAIL 15-Columbia Dennis Moore BRICK BRADFORD 15-Columbia Kane Richmond BRUCE GENTRY 15-Columbia Tom Neal BUCK ROGERS 12-Universal Buster Crabbe BURN'EM UP BARNES 12-Mascot Jack Mulhall CALL OF THE SAVAGE 13-Universal Noah Berry, Jr. CANADIAN MOUNTIES v/s ATOMIC INVADERS 12-Republic Bill Henry CAPTAIN AMERICA 15-Republic Dick Pucell CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT 15-Columbia Dave O'Brien CAPTAIN VIDEO 15-Columbia Judd Holdren CHICK CARTER, DETECTIVE 15-Columbia Lyle Talbot THE CLUTCHING HAND 15-Independent Jack Mulhall CODY OF THE PONY EXPRESS 15-Columbia Jock Mahoney CONGO BILL 15-Columbia Don McGuire THE CRIMSON GHOST 12-Republic -

Gaó E Seu Ritmo No T&Xto

24." Ano ::•-:: N.° 47 l\ de Novembro de 1944 Vi^y^ Cr $ 1,20 ?\ ^^m\r a^^ Ts^^f^S aW // **^j€ ( nos Estados 1,50 REVISTA á^y C ATUALIDADES -¦¦-.--.¦'•'-'':!}';''"''" ~ ' '.1. f í 'f?$->$'¦-" >J'-' /"-"'7"'"ííi--"'-L.^^Httí' jfl?BWOTr^>:"i í-v."'.O-'-'O.;- -:O'-^^"^^P'4^ÍS"5ttWB H^T'.¦""*¦¦-,.L--:"-~mmm^ÊB0£^y -""^^^*='•*¦V' ' — «f^--' Gaó e seu ritmo No T&xto Wi WÈÊÊÉÈÊSm lllllll mito mmm ¦¦:¦¦¦¦¦:¦:-:¦:-.¦:¦ 31 iimniiji rjKimnnuiirniMisia'!1 "X"< tír"*8^ ^ ""Tú roí ti (-haNDE ENCANTO of a» I Ha' U/)RIAS" E 8E A^UNTVERSAL I.HK DF* •«Aa8 OPORTUNIDADES ÍRÀ LONOR. "OEííCOBERTii". C%wh fe nMt ORANDV jMÉlf 1!!!>>.,X>»J!>.)£»M»WPW; VMfM',»-'. -u .WW-H.XXBS Uma vrz mais, Joan Fontaine aceitou um papel que maioria dar público aclamou-a como a tímida heroina de REBECA. Logo em re- li "glamoui". estrelas" consideiaiia indesejável, poi sei destituído de guida conquistou todos os corações em SUSPEITA, a despeito de ura E não somente o aceitou, poiém fez dele um dos seus mais destacados horrível par de óculos de osso. E um simples uniforme d*s WAAF, tiiunfos. A iimã de Olivia de Havilknd apaiece no papel-título de com seus sapatos militares e suas meias de algodão, serviu apenrs para JANE EYRE, a moderna versão cinematográfica do romance de realçar sua beleza patrícia, em ISTO ACIMA DE TUDO. Em DE Oha;lotte Bionte, a 20th-Fox íealizou crm tanto caiiriho. AMOR TAMBÉM SE MORRE, que "Todos também esteve adorável. "mas No papel de Jane, bonita, sim, mas sempre metida^ em severos e esses papeis tinham suas desvantagens", diz Joan, simples vestidos escuros e usando um penteado clássico sem faceí- certamente não é este característico que torna JANE EYRE um grande lice, ela só uma vez tem opoitunidad.e de apa.ecer em toda a sua bele- Pcís nenhum dos outros de intei- — papel. -

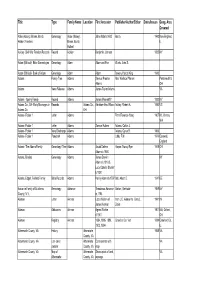

Vertical File

Title Type Family Name Location First Ancestor Publisher/Author/Editor Dates/Issues Geog. Area Covered Abbe (Abbey), Brown, Burch, Genealogy Abbe (Abbey), John Abbe b.1613 Burch 1943 New England, Hulbert Families Brown, Burch, IL Hulbert Ackley- Civil War Pension Records Record Ackley Benjamin Johnson 1832 NY Adam (Biblical)- Bible Genealogies Genealogy Adam Adam and Eve Wurts, John S. Adam (Biblical)- Book of Adam Genealogy Adam Adam Bowen, Harold King 1943 Adams Family Tree Adams Samuel Preston Mrs. Wallace Phorsm Portsmouth & Adams OH Adams News Release Adams James Taylor Adams VA Adams - Spring Family Record Adams James Wamorth? 1832 NY Adams Co., OH- Early Marriages in Records Adams Co., Abraham thru Wilson Ackley, Robert A. 1982 US Adams Co. OH Adams- Folder 1 Letter Adams From Florence Hoag 1907 Mt. Vernon, WA Adams- Folder 1 Letter Adams Samuel Adams Adams, Calvin J. Adams- Folder 1 Navy Discharge Adams Adams, Cyrus B. 1866 Adams- Folder 1 Pamphlet Adams Lobb, F.M. 1979 Cornwall, England Adams- The Adams Family Genealogy/ Tree Adams Jacob Delmar Harper, Nancy Eyer 1978 OH Adams b.1858 Adams, Broyles Genealogy Adams James Darwin KY Adams b.1818 & Lucy Ophelia Snyder b.1820 Adams, Edgell, Twiford Family Bible Records Adams Henry Adams b.1797 Bell, Albert D. 1947 DE Adriance Family of Dutchess Genealogy Adriance Theodorus Adriance Barber, Gertrude 1959 NY County, N.Y. m.1783 Aikman Letter Aikman Lists children of from L.C. Aikman to Cora L. 1941 IN James Aikman Davis Aikman Obituaries Aikman Agnes Ritchie 1901 MA, Oxford, d.1901 OH Aikman Registry Aikman 1884, 1895, 1896, Crawford Co. -

Sound Evidence: an Archaeology of Audio Recording and Surveillance in Popular Film and Media

Sound Evidence: An Archaeology of Audio Recording and Surveillance in Popular Film and Media by Dimitrios Pavlounis A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Screen Arts and Cultures) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Sheila C. Murphy, Chair Emeritus Professor Richard Abel Professor Lisa Ann Nakamura Associate Professor Aswin Punathambekar Professor Gerald Patrick Scannell © Dimitrios Pavlounis 2016 For My Parents ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My introduction to media studies took place over ten years ago at McGill University where Ned Schantz, Derek Nystrom, and Alanna Thain taught me to see the world differently. Their passionate teaching drew me to the discipline, and their continued generosity and support made me want to pursue graduate studies. I am also grateful to Kavi Abraham, Asif Yusuf, Chris Martin, Mike Shortt, Karishma Lall, Amanda Tripp, Islay Campbell, and Lees Nickerson for all of the good times we had then and have had since. Thanks also to my cousins Tasi and Joe for keeping me fed and laughing in Montreal. At the University of Toronto, my entire M.A. cohort created a sense of community that I have tried to bring with me to Michigan. Learning to be a graduate student shouldn’t have been so much fun. I am especially thankful to Rob King, Nic Sammond, and Corinn Columpar for being exemplary scholars and teachers. Never have I learned so much in a year. To give everyone at the University of Michigan who contributed in a meaningful way to the production of this dissertation proper acknowledgment would mean to write another dissertation-length document. -

Journal of the Speech and Theatre Association of Missouri Volume XLIV, Fall 2014 Published by the Speech and Theatre Association of Missouri – ISSN 1073-8460

Speech and Theatre Association of Missouri Officers President Michael Hachmeister Parkway South High School Vice-President Carla Miller Wydown Middle School Vice-President Elect Lara Corvera Pattonville High School Immediate Past-President Jeff Peltz University of Central Missouri Executive Secretary Scott Jensen Webster University Director of Publications Gina Jensen Webster University Board of Governors Melissa Joy Benton, STLCC – Florissant & Webster Univ. 2014 Todd Schnake, Raymore-Peculiar High School 2014 David Watkins, Neosho High School 2014 Jamie Yung, Lexington High School 2014 Brian Engelmeyer, Wydown Middle School 2015 Matt Good, Lee's Summit West High School 2015 Paul Hackenberger, Winnetonka High School 2015 Maureen Kelts, Delta Woods Middle School 2015 Molly Beck, Ladue Horton Watkins High School 2016 Brad Rackers, Lee's Summit West High School 2016 Justin Seiwell, Clayton High School 2016 Teri Turner, Smith-Cotton High School 2016 Historian Shannon Johnson University of Central Missouri Student Liason John O’Neil Missouri State University Director of Electronic Communications Brian Engelmeyer Wydown Middle School Ex. Officio Member Dr. Melia Franklin DESE Fine Arts www.speechandtheatremo.org i Journal of the Speech and Theatre Association of Missouri Volume XLIV, Fall 2014 Published by the Speech and Theatre Association of Missouri – ISSN 1073-8460 Scholarly Articles Motivations for Friendship: Russia, Croatia and United States 1 Deborrah Uecker, Jacqueline Schmidt, Aimee Lau Moving the Stage 17 William Schlichter Great