5. Repetition, Reiteration, and Reenactment: Operational Detection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

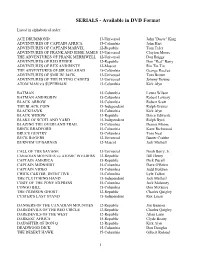

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format Listed in alphabetical order: ACE DRUMMOND 13-Universal John "Dusty" King ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN AFRICA 15-Columbia John Hart ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL 12-Republic Tom Tyler ADVENTURES OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES 13-Universal Clayton Moore THE ADVENTURES OF FRANK MERRIWELL 12-Universal Don Briggs ADVENTURES OF RED RYDER 12-Republic Don "Red" Barry ADVENTURES OF REX AND RINTY 12-Mascot Rin Tin Tin THE ADVENTURES OF SIR GALAHAD 15-Columbia George Reeves ADVENTURES OF SMILIN' JACK 13-Universal Tom Brown ADVENTURES OF THE FLYING CADETS 13-Universal Johnny Downs ATOM MAN v/s SUPERMAN 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BATMAN 15-Columbia Lewis Wilson BATMAN AND ROBIN 15-Columbia Robert Lowery BLACK ARROW 15-Columbia Robert Scott THE BLACK COIN 15-Independent Ralph Graves BLACKHAWK 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BLACK WIDOW 13-Republic Bruce Edwards BLAKE OF SCOTLAND YARD 15-Independent Ralph Byrd BLAZING THE OVERLAND TRAIL 15-Columbia Dennis Moore BRICK BRADFORD 15-Columbia Kane Richmond BRUCE GENTRY 15-Columbia Tom Neal BUCK ROGERS 12-Universal Buster Crabbe BURN'EM UP BARNES 12-Mascot Jack Mulhall CALL OF THE SAVAGE 13-Universal Noah Berry, Jr. CANADIAN MOUNTIES v/s ATOMIC INVADERS 12-Republic Bill Henry CAPTAIN AMERICA 15-Republic Dick Pucell CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT 15-Columbia Dave O'Brien CAPTAIN VIDEO 15-Columbia Judd Holdren CHICK CARTER, DETECTIVE 15-Columbia Lyle Talbot THE CLUTCHING HAND 15-Independent Jack Mulhall CODY OF THE PONY EXPRESS 15-Columbia Jock Mahoney CONGO BILL 15-Columbia Don McGuire THE CRIMSON GHOST 12-Republic -

Media Contingency in the 1930S

6. Sound Serials: Media Contingency in the 1930s Abstract Chapter 6 traces the impact of radio and television on the serials’ mode of address, as the golden era of serials in the mid-1930s and early 1940s coincided with the heyday of radio and the discursive consolidation of television as a broadcast medium in the United States. Film serials embraced the narrative forms and modes of address of radio and television and simultaneously reactivated possibilities offered by these media that were discursively negated at the time, for instance the use of television for point-to-point communication. In showcasing these options, serials not only reinstated full contingency at the historical moment of its curtailing, they also extended their own array of options of storytelling, managing a variety of anecdotes and adopted forms to exhibit and juxtapose multiple modes of address. Keywords: film serials, history of television, history of radio, Gene Autry, transmedia, convergence culture In the 1930s, serials found themselves entangled in a network of multifarious established and emerging media to an unprecedented extent. Radio had become an established mass medium, sound film was fully consolidated, newspaper comic strips were experiencing their heyday, and television was looming large on the horizon. In fact, the ‘golden era’ of film serials, which Higgins locates between 1936-1946 (2016: 98), coincides with the heyday of radio from 1937-1946 (Hilmes 1997: 184) as well as with the conceptual consolidation—although not yet the dissemination—of television in the mid-1930s (Sewell 2014: 44). At the time, serials picked up on characters and narratives from the popular daily ‘funnies’, which often already sported their own radio serials. -

TEXTOS TEÓRICOS En Tebeosfera

TEBEOSFERA / DOCUMENTOS / TEXTOS TIRAS NEGRAS: EL GÉNERO NEGRO EN LAS SERIES DE PRENSA ESTADOUNIDENSES TIRAS NEGRAS: EL GÉNERO NEGRO EN LAS SERIES DE PRENSA ESTADOUNIDENSES (TEBEOSFERA, SEVILLA, XII-2002) PORTADA SUMARIO Autor: JESÚS JIMÉNEZ VAREA CATÁLOGOS Publicado en: TEBEOSFERA 2ª EPOCA 6 ACTUALIDAD CONCEPTOS Publicado en: YELLOW KID (GIGAMESH, 2002) 4 AUTORES Páginas: 19 (2-20) Fecha: XII-2002 OBRAS DOCUMENTOS Notas: Texto aparecido originalmente en el número 4 de EVENTOS la revista teórica Yellow Kid en diciembre de 2002, y recuperado ahora en Tebeosfera con SITIOS permiso de su autor. El párrafo introductorio, así como los textos de los pies de imágenes, no son 1ª ÉPOCA de J. Jiménez Varea. TEBEOSBLOG Primera página de este NAVEGAR documento. COLABORAR DONAR ASOCIACIÓN IDENTIDAD TIRAS NEGRAS: EL GÉNERO DOC. LEGAL CONTACTOS NEGRO EN LAS SERIES DE PRENSA CRÉDITOS ESTADOUNIDENSES. BUSCAR Metralletas y persecuciones, la Prohibición, jazz, héroes muy recios, femmes fatales BUSCAR CON y crueles hampones deformes que, a veces, fueron la caricatura de sí mismos. Todos los temas recurrentes del género negro tuvieron y aún tienen su perfecta plasmación en el medio de la historieta, donde alternan sin ningún tipo de complejos nombres de escritores reconocidos como Dashiell Hammett, Mickey This PDF was generated via the PDFmyURL web conversion service! Spillane o Max Allan Collins con los de artistas de primera línea como Alex Raymond, Alfred Andriola o Elliot Gould. Intento de estupro y allanamiento de morada en Don Juan, explotación infantil y estafa en El Lazarillo de Tormes, escándalo público y vandalismo en Don Quijote, conspiración y magnicidio en Fuenteovejuna, secuestro en La vida es sueño.. -

Of Film Titles

Index of Film Titles Ace Drummond 107-12, 130, 256 n. 23, 268-77, Hash House Fraud, a 209 image 24 280 Hands Up! 104 n. 31 Ace of Scotland Yard 104 n. 31 Hazards of Helen, the 82, 87 n. 6, 104 n. 32, Adventures of Fu Manchu, the (TV) 290 203 n. 1 Hidden Dangers 216 n. 29 Adventures of Kathlyn, the 10, 89, 201 n. 18 Hit the Saddle 134 Adventures of Tarzan, the 99 Holt of the Secret Service 106 n. 35, 108 Amazing Exploits of the Clutching Hand, n. 42, 110 n. 48, 112 n. 53, 130, 286 the 105, 133-36, 216, 259 n. 26, 268-69, 277 Hope Diamond Mystery, the 36, 98, 104 n. 32, L’Arroseur Arrosé 70-71, 160 117 n. 59, 183-85, 195-207, 211, 215, 228, 272 As Seen Through a Telescope 169 n. 37 Atomic Raiders, the 297 House of Hate, the 155 n. 11, 285 Batman 11, 279 n. 43 Indians are Coming, the 104, 104 nn. 30-31 Beloved Adventurer, the 13, 83, 89 n. 12, Interrupted Lovers 169 115-16 Intolerance 197, 200 n. 16 Black Box, the 216 n. 29 Black Diamond Express, the 188 Jazz Singer, the 104 Black Secret, the 99 Blazing the Overland Trail 288 King of the Kongo, the 104, 104 n. 31 King of the Royal Mounted 107 Captain America 106 n. 35, 110 nn. 48-49, 111 Kiss, the 168 n. 50, 132 Kleptomaniac, the 169 Captain Midnight 107 n. 40, 110 nn. 47-49, 111 n. -

A Brief History of Comic Book Movies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-47184-6 80 BIBLIOGRAPHY

BIBLIOGRAPHY Akitunde, Anthonia. 2011 X-Men: First Class. Fast Company, May 18. Web. Alaniz, José. 2015. Death, Disability, and the Superhero: The Silver Age and Beyond. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. Print. Arnold, Andrew. 2001. Anticipating a Ghost World. Time, July 20. Web. Booker, M. K. 2007. May Contain Graphic Material: Comic Books, Graphic Novels, and Film. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. Print. ———. 2001. Batman Unmasked: Analyzing a Cultural Icon. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. Print. Brenner, Robin E. 2007. Understanding Manga and Animé. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited. Print. Brock, Ben. 2014, February 4. Bryan Singer Says Superman Returns was Made for “More of a Female Audience,” Sequel Would’ve Featured Darkseid. The Playlist. Web. Brooker, Will. 2012. Hunting the Dark Knight: Twenty-First Century Batman. London: I.B. Tauris. Print. Brown, Steven T. 2010. Tokyo Cyberpunk: Posthumanism in Japanese Visual Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Print. ———. 2006. Cinema Animé: Critical Engagements with Japanese Animation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Print. Bukatman, Scott. 2016. Hellboy’s World: Comics and Monsters on the Margins. Berkeley: University of California Press. Print. ———. 2011. Why I Hate Superhero Movies. Cinema Journal 50(3): 118–122. Print. Burke, Liam. 2015. The Comic Book Film Adaptation: Exploring Modern Hollywood’s Leading Genre. University Press of Mississippi. Print. ———. 2008. Superhero Movies. Harpenden, England: Pocket Essentials. Print. © The Author(s) 2017 79 W.W. Dixon, R. Graham, A Brief History of Comic Book Movies, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-47184-6 80 BIBLIOGRAPHY Caldecott, Stratford. 2013. Comic Book Salvation. Chesterton Review 39(1/2): 283–288. Print. Chang, Justin. 2014, August 20. -

Guide to the Motion Picture Stills Collection 1920-1934

University of Chicago Library Guide to the Motion Picture Stills Collection 1920-1934 © 2006 University of Chicago Library Table of Contents Descriptive Summary 3 Information on Use 3 Access 3 Citation 3 Scope Note 3 Related Resources 5 Subject Headings 5 INVENTORY 6 Series I: Actors and Actresses 6 Series II: Motion Picture Stills 171 Series III: Scrapbooks 285 Subseries 1: Scrapbooks; Individual Actors and Actresses 285 Subseries 2: Miscellaneous Scrapbooks 296 Series IV: Vitaphone Stills 297 Series V: Large Film Stills and Marquee Cards 300 Series VI: Coming Attractions, Glass Lantern Slides 302 Series VII: Duplicate Film Stills 302 Series VIII: Index Cards 302 Descriptive Summary Identifier ICU.SPCL.MOTIONPICTURE Title Motion Picture Stills. Collection Date 1920-1934 Size 87.5 linear feet (139 boxes) Repository Special Collections Research Center University of Chicago Library 1100 East 57th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 U.S.A. Abstract Contains approximately 30,000 black and white photographs of movie stills, production shots, and portrait photographs of actors. Includes 8" x 10" photographs, 187 scrapbooks devoted to individual film stars, marquee cards, and glass lantern slides announcing coming attractions from Pathe and other movie studios. Information on Use Access No restrictions. Citation When quoting material from this collection, the preferred citation is: Motion Picture Stills. Collection, [Box #, Folder #], Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library Scope Note The Motion Picture Stills Collection features a group of approximately 30,000 black and white photographs of movie stills, production shots, and portrait photographs of actors. The first half of this collection consists of these 8" x 10" photographs. -

1 Senile Celluloicl': Lnclepenclent Exltiijitors, Tite Major Stuclios Ancl Tite Figltt Over Feature Films on Television, 1939-1956

Film History, Volume 1O, pp. 141-164, 1998. Text copyright ©David Pierce 1998. Design copyright ©John Libbey & Company ISSN: 0892-2160. Printed in Australia 1 David Pierce he Presiden! of RKO received many letters American representative, noted, 'television is pre from motion picture exhibitors. The corre ciselythe same visual medium as theatres offer-this spondence from the Allied Theatre Owners isn't night baseball or radio or sorne other entirely T of New Jersey complained about RKO 'fur different form of competition'. 2 nishing films for use over television'. Their concerns In 1939, RKO's participation in television was were simple: 'You can readily understand that if our tentative. The studio had supplied a trailer for patrons are able lo see a picture such as Gunga Din Gunga Din for sorne experimental television tests in on their television seis al home, they are not likely to come into the theater.' Pointing out that this was in their mutual interest, the letter concluded that '[we] urge that you discontinue this practice. The exhibitor has enough lo contend with lo keep his house open during these depressing times' .1 Depressing times? Yes, this letter was written in 1939, and exhibitors already recognised that television would threaten their very existence. They had survived the introduction of radio intoAmerican life, but as Morris Helprin, Sir Alexander Korda's Film History, Volume 10, pp . 141 - 164, 1998. Text copyright © David Pierce 1998. Design copyright © John libbey & Compony ISSN : 0892-2 160. Printed in Austra lia 1 Senile celluloicl': lnclepenclent exltiiJitors, tite major stuclios ancl tite figltt over feature films on television, 1939-1956 David Pierce he Presiden! of RKO received many letters American representative, noted, 'television is pre from motion picture exhibitors. -

Poverty Row Films of the 1930S by Robert J Read Department of Art History and Communication Studies

A Squalid-Looking Place: Poverty Row Films of the 1930s by Robert J Read Department of Art History and Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal August 2010 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or by other means, without permission of the author. Robert J Read, 2010. ii Abstract Film scholarship has generally assumed that the low-budget independent film studios, commonly known as Poverty Row, originated in the early sound-era to take advantage of the growing popularity of double feature exhibition programs. However, the emergence of the independent Poverty Row studios of the 1930s was actually the result of a complex interplay between the emerging Hollywood studios and independent film production during the late 1910s and 1920s. As the Hollywood studios expanded their production, as well as their distribution networks and exhibition circuits, the independent producers that remained outside of the studio system became increasingly marginalized and cut-off from the most profitable aspects of film exhibition. By the late 1920s, non-Hollywood independent film production became reduced to the making of low-budget action films (westerns, adventure films and serials) for the small profit, suburban neighbourhood and small town markets. With the economic hardships of the Depression, the dominant Hollywood studios were forced to cut-back on their lower budgeted films, thus inadvertently allowing the independent production companies now referred to in the trade press as Poverty Row to expand their film practice. -

FILM SERIALS and the AMERICAN CINEMA 1910-1940 OPERATIONAL DETECTION Ilka Brasch Film Serials and the American Cinema, 1910-1940

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION FILM SERIALS and the AMERICAN CINEMA 1910-1940 OPERATIONAL DETECTION ilka brasch Film Serials and the American Cinema, 1910-1940 Film Serials and the American Cinema, 1910-1940 Operational Detection Ilka Brasch Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Pearl White shooting scenes for The Perils of Pauline in Fort Lee, 1914. Photo Courtesy of the Fort Lee Film Commission of Fort Lee, NJ USA. Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 94 6298 652 7 e-isbn 978 90 4853 780 8 doi 10.5117/9789462986527 nur 670 © I. Brasch / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2018 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. Table of Contents Acknowledgements 7 1. Introduction 9 2. The Operational Aesthetic 43 3. Film Serials Between 1910 and 1940 81 4. Detectives, Traces, and Repetition in The Exploits of Elaine 145 5. Repetition, Reiteration, and Reenactment: Operational Detection 183 6. Sound Serials: Media Contingency in the 1930s 235 7. -

L'era Dei Cliffhanger Serials

FUMETTO L’excursus dedicato agli spy fumetti prosegue L’era dei cliffhanger serials con i cliffhanger serials , espediente narrativo che interrompeva temporaneamente la vicenda GIUSEPPE POLLICELLI in un momento di particolare tensione. La prima trasposizione cinematografica di cliffhanger seriale fu Tailspin Tommy (1934), il cui protagonista era uno spericolato pilota. Sull’onda del successo gli fu dedicato il nuovo serial The Great Air Mystery (1935). Fu poi la volta di Flash Gordon (1936), cui seguirà una lunga teoria di film a puntate ricavati dalle vicende di Jungle Jim, Dick Tracy, Mandrake, Secret Agent X-9, Superman, Batman e Captain America . Tra le serie che si misurarono con il genere spionistico, degna di nota è quella centrata sul fumetto di Spy Smasher (1942), un agente che dispone di strabilianti mezzi tra i quali un avveniristico veicolo, fusione tra un aeroplano, Fumetto di Spy Smasher , 1942; un’automobile e un sottomarino. in basso, locandina del cliffhanger serial di Don Winslow of the Navy , 1941. termine della precedente pun - Charles Clarence Beck. La trasposizione tata di questo excursus dedicato sul grande schermo di Don Winslow of the Al ai fumetti di argomento spioni - Navy e, l’anno successivo, di Spy Smasher stico ci siamo occupati di un personaggio rende necessario soffermarsi su un feno - creato nel 1934 dallo sceneggiatore Frank meno che, sotto il profilo dei consumi cul - V. Martinek (ex membro del controspio - turali è stato decisamente rilevante negli naggio) e dal disegnatore Leon A. Beroth, Stati Uniti -

Big Little Books List

Rare Book Team - Processing Plans - Default Big Little Book Collection in the Rare Book and Special Collections Division of the Library of Congress Title List Preliminary draft compiled by Belinda D. Urquiza, March 12, 1986 Revised by James Hafner, December 11, 2003 TERMINOLOGY BLB (Big Little Book). Used to cover only Whitman books. col. ill. (color illustration). Books containing color illustrations. FAS (Fast Action Stories). Books having a BLB format, printed by Whitman for Dell Publishing Company. FM (flip movie). BLBs that contain small pictures in an upper corner of every page. The pages were flipped to give the impression of motion. ill. Book contains illustrations. movie. Books containing photos from movies. nn (no number). Books produced without a series number. O (oversized). Books that were larger in format than the regular issues photos (photographs). Books containing photographs but not from movies. REFERENCE WORKS Lowery, Lawrence F. “Lowery's The collector's guide to big little books and similar books.” Danville, Calif. : Educational Research and Applications Corp., c1981. biglittlebooksFA.htm[4/16/2015 2:13:39 PM] Rare Book Team - Processing Plans - Default Thomas, James Stuart. "The Big Little Book Price Guide." Des Moines, Iowa : Wallace-Homestead Book Co., c1988. BACKGROUND A variety of children's books in special formats that were nearly all received through copyright deposit in the 1930s and the 1940s. Most numerous are the "Big Little Books" and "Better Little Books" issued by Whitman Publishing company, a subsidiary of the Western Printing & Lithographing Company (now Western Publishing Company) of Racine, Wisconsin. ORGANIZATION The following list of the 467 books in the Big Little Book Collection is listed alphabetically by title. -

Big Little Books Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1c6035gr No online items Big Little Books Collection Sara Gunasekara Department of Special Collections General Library University of California, Davis Davis, CA 95616-5292 Phone: (530) 752-1621 Fax: (530) 754-5758 Email: [email protected] © 2011 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Big Little Books Collection D-480 1 Creator: Whitman Publishing Company Title: Big Little Books Collection Date (inclusive): 1933-1948 Extent: 10.4 linear feet Abstract: The Big Little Books, a series of small books published by the Whitman Publishing Company, consist of stories based on comic strips, radio dramas, and popular fiction. This collection contains 193 volumes, including titles from the following series: Dick Tracy, Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, and Popeye. Physical location: Researchers should contact Special Collections to request collections, as many are stored offsite. Repository: University of California, Davis. General Library. Dept. of Special Collections. Davis, California 95616-5292 Collection number: D-480 Language of Material: Collection materials in English. Administrative History The Big Little Books are a series of small books published by the Whitman Publishing Company. They consist of stories based on comic strips, radio dramas, and popular fiction. Scope and Content The collection contains 193 Big Little Books including titles from the following series: Dick Tracy, Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, and Popeye. Arrangement of the Collection The collection is arranged in alphabetical order by title. Indexing Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the library's online public access catalog. Whitman Publishing Company Big little books Comic books, strips, etc.