In Search of Stephen: the Wartime Death of an American Airman in World War II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Luftwaffe Wasn't Alone

PIONEER JETS OF WORLD WAR II THE LUFTWAFFE WASN’T ALONE BY BARRETT TILLMAN he history of technology is replete with Heinkel, which absorbed some Junkers engineers. Each fac tory a concept called “multiple independent opted for axial compressors. Ohain and Whittle, however, discovery.” Examples are the incandes- independently pursued centrifugal designs, and both encoun- cent lightbulb by the American inventor tered problems, even though both were ultimately successful. Thomas Edison and the British inventor Ohain's design powered the Heinkel He 178, the world's first Joseph Swan in 1879, and the computer by jet airplane, flown in August 1939. Whittle, less successful in Briton Alan Turing and Polish-American finding industrial support, did not fly his own engine until Emil Post in 1936. May 1941, when it powered Britain's first jet airplane: the TDuring the 1930s, on opposite sides of the English Chan- Gloster E.28/39. Even so, he could not manufacture his sub- nel, two gifted aviation designers worked toward the same sequent designs, which the Air Ministry handed off to Rover, goal. Royal Air Force (RAF) Pilot Officer Frank Whittle, a a car company, and subsequently to another auto and piston 23-year-old prodigy, envisioned a gas-turbine engine that aero-engine manufacturer: Rolls-Royce. might surpass the most powerful piston designs, and patented Ohain’s work detoured in 1942 with a dead-end diagonal his idea in 1930. centrifugal compressor. As Dr. Hallion notes, however, “Whit- Slightly later, after flying gliders and tle’s designs greatly influenced American savoring their smooth, vibration-free “Axial-flow engines turbojet development—a General Electric– flight, German physicist Hans von Ohain— were more difficult built derivative of a Whittle design powered who had earned a doctorate in 1935— to perfect but America's first jet airplane, the Bell XP-59A became intrigued with a propeller-less gas- produced more Airacomet, in October 1942. -

The Reich Wreckers: an Analysis of the 306Th Bomb Group During World War II 5B

AU/ACSC/514-15/1998-04 AIR COMMAND AND STAFF COLLEGE AIR UNIVERSITY THE REICH WRECKERS: AN ANALYSIS OF THE 306TH BOMB GROUP DURING WORLD WAR II by Charles J. Westgate III, Major, USAF A Research Report Submitted to the Faculty In Partial Fulfillment of the Graduation Requirements Advisor: Dr. Richard R. Muller Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 1998 REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burder for this collection of information is estibated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burder to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE (DD-MM-YYYY) 2. REPORT TYPE 3. DATES COVERED (FROM - TO) 01-04-1998 Thesis xx-xx-1998 to xx-xx-1998 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER The Reich Wreckers: An Analysis of the 306th Bomb Group During World War II 5b. GRANT NUMBER Unclassified 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. -

86'- ' Its Departure for Overseas Duty in Great Britain

CHAa IV *I 'THE STORY OP VIII FIGHT CM " began The formation of a long-range fighter organization VIII Interceptor early in 1942 with the activation of the Fighter Comnand, at Coand, which later was renamed the VIII 1, 1942. The Comanding Selfridge Field, Michigan on February who had been in oamand Officer was Colonel Laurence P. Hiokey, VIII Interceptor of the Sixth Pursuit Wing, from which the to Charleston, South Command was developed. The Command moved to be close to the Carolina on the 11th of February in. order located at Savannah, headquarters of the 8th Air Force, then The 8th Air Georgia, where it was preparing for embarkation. be prepared to carry Force was organised in such a way aa to invasion of North Afrioa out the "Torch Plan' for the eventual General Frank O'D. which oame in November, 1942. Brigadier shortly before Hunter assumed oommand of the organisation Officer Richard The author is indebted to Chief Warrant (*1 - at VIII Fighter A. Bates of the A-2 Section (Intelligence) history of the Comnand. Comand for the facts about the early whn it _as activated in Febru- Mr. Bates was its lst Stergeant of the became Teohnical Sergeant ana Chief Olerk ary, 1942, hiatorian until July IntelligenCe Section and was its official data was not otherwise available. The Sta- 1943. Much of this later, has Control Office which was establiahed muoh tistical but these facts proided-invaluable data on later operations, from his own records, from his friends "'oaptured for posterity" are based on his and from a most retentive memory. -

Bendheim Senior Thesis Department of History, Columbia University

INCENDIARY WARS: The Transformation of United States Air Force Bombing Policy in the WWII Pacific Theater Gilad Bendheim Senior Thesis Department of History, Columbia University Faculty Advisor: Professor Mark Mazower Second Reader: Professor Alan Brinkley INCENDIARY WARS 1 Note to the Reader: For the purposes of this essay, I have tried to adhere to a few conventions to make the reading easier. When referring specifically to a country’s aerial military organization, I capitalize the name Air Force. Otherwise, when simply discussing the concept in the abstract, I write it as the lower case air force. In accordance with military standards, I also capitalize the entire name of all code names for operations (OPERATION MATTERHORN or MATTERHORN). Air Force’s names are written out (Twentieth Air Force), the bomber commands are written in Roman numerals (XX Bomber Command, or simply XX), while combat groups are given Arabic numerals (305th Bomber Group). As the story shifts to the Mariana Islands, Twentieth Air Force and XXI Bomber Command are used interchangeably. Throughout, the acronyms USAAF and AAF are used to refer to the United States Army Air Force, while the abbreviation of Air Force as “AF” is used only in relation to a numbered Air Force (e.g. Eighth AF). Table of Contents: Introduction 3 Part I: The (Practical) Prophets 15 Part II: Early Operations Against Japan 43 Part III: The Road to MEETINGHOUSE 70 Appendix 107 Bibliography 108 INCENDIARY WARS 2 Introduction Curtis LeMay sat awake with his trademark cigar hanging loosely from his pursed ever-scowling lips (a symptom of his Bell’s Palsy, not his demeanor), with two things on his mind. -

United States Air Force and Its Antecedents Published and Printed Unit Histories

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AND ITS ANTECEDENTS PUBLISHED AND PRINTED UNIT HISTORIES A BIBLIOGRAPHY EXPANDED & REVISED EDITION compiled by James T. Controvich January 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS User's Guide................................................................................................................................1 I. Named Commands .......................................................................................................................4 II. Numbered Air Forces ................................................................................................................ 20 III. Numbered Commands .............................................................................................................. 41 IV. Air Divisions ............................................................................................................................. 45 V. Wings ........................................................................................................................................ 49 VI. Groups ..................................................................................................................................... 69 VII. Squadrons..............................................................................................................................122 VIII. Aviation Engineers................................................................................................................ 179 IX. Womens Army Corps............................................................................................................ -

PEN (Organization)

PEN (Organization): An Inventory of Its Records at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: PEN (Organization) Title: PEN (Organization) Records Dates: 1912-2008 (bulk 1926-1997) Extent: 352 document boxes, 5 card boxes (cb), 5 oversize boxes (osb) (153.29 linear feet), 4 oversize folders (osf) Abstract: The records of the London-based writers' organizations English PEN and PEN International, founded by Catharine Amy Dawson Scott in 1921, contain extensive correspondence with writer-members and other PEN centres around the world. Their records document campaigns, international congresses and other meetings, committees, finances, lectures and other programs, literary prizes awarded, membership, publications, and social events over several decades. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-03133 Language: The records are primarily written in English with sizeable amounts in French, German, and Spanish, and lesser amounts in numerous other languages. Non-English items are sometimes accompanied by translations. Note: The Ransom Center gratefully acknowledges the assistance of the National Endowment for the Humanities, which provided funds for the preservation, cataloging, and selective digitization of this collection. The PEN Digital Collection contains 3,500 images of newsletters, minutes, reports, scrapbooks, and ephemera selected from the PEN Records. An additional 900 images selected from the PEN Records and related Ransom Center collections now form five PEN Teaching Guides that highlight PEN's interactions with major political and historical trends across the twentieth century, exploring the organization's negotiation with questions surrounding free speech, political displacement, and human rights, and with global conflicts like World War II and the Cold War. Access: Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. -

There Is a Map of Sawston Is HERE to Assist with Locations Mentioned.)

(A Streetfull of Sad Sacks has been published on this site, without the authority of the author or publisher, after extensive enquiry to discover their identity and permission. Searches have been made in the USA, to seek this authority, via the Air Force Historical Research Agency http://www.afhra.af.mil/ and the Muir S. Fairchild Research Information Center without any trace. ) (There is a map of Sawston is HERE to assist with locations mentioned.) (Examine this location in Google Street View.) DURING THE SUMMER OF 1943 UNITS OF THE UNITED STATES ARMY AND ITS EIGHTH AIR FORCE MOVED INTO SAWSTON, WHEN THEY LEFT IN OCTOBER 1945, LIFE IN THE VILLAGE WAS NEVER QUITE THE SAME AGAIN Page 1 of 75 www.family.nigellane.com The Sad Sack An embodiment of the Army's lowest-rated born loser, George Baker's cartoon character made his name in World War Two as the hapless draftee who lost out in every conceivable military situation. Sergeant Baker's comic strip in the service magazine Yank, published on Sundays price 3d, depicted the Sack's confrontations with the perils and perplexities of wartime service life. In all his dealings - with fellow soldiers, top brass, foreign nationals, prostitutes and the rest of the world in general - the little private always came off second best. But he remained the Army's hero, a trusting soul whose own little world of dreamy optimism was constantly devastated by unforeseen disaster. His name derived from the drill sergeant’s parade-square name for all new doughboys. To that redoubtable NCO all recruits were "sad -

2007 Lnstim D'hi,Stoire Du Temp

WORLD "TAR 1~WO STlIDIES ASSOCIATION (formerly American Committee on the History ofthe Second World War) Mark P. l'arilIo. Chai""an Jona:han Berhow Dl:pat1menlofHi«ory E1izavcla Zbeganioa 208 Eisenhower Hall Associare Editors KaDsas State University Dct>artment ofHistory Manhattan, Knnsas 66506-1002 208' Eisenhower HnJl 785-532-0374 Kansas Stale Univemty rax 785-532-7004 Manhattan, Kansas 66506-1002 parlllo@,'<su.edu Archives: Permanent Directors InstitlJle for Military History and 20" Cent'lly Studies a,arie, F. Delzell 22 J Eisenhower F.all Vandcrbijt Fai"ersity NEWSLETTER Kansas State Uoiversit'j Manhattan, Kansas 66506-1002 Donald S. Detwiler ISSN 0885·-5668 Southern Ulinoi' Va,,,,,,,sity The WWT&« is a.fIi!iilI.etf witJr: at Ccrbomlale American Riston:a1 A."-'iociatioG 400 I" Street, SE. T.!rms expiring 100(, Washingtoo, D.C. 20003 http://www.theah2.or9 Call Boyd Old Dominio" Uaiversity Comite internationa: dlli.loire de la Deuxii:me G""",, Mondiale AI"".nde< CochrnIl Nos. 77 & 78 Spring & Fall 2007 lnstiM d'Hi,stoire du Temp. PreSeDt. Carli5te D2I"n!-:'ks, Pa (Centre nat.onal de I. recberche ,sci,,,,tifiqu', [CNRSJ) Roj' K. I'M' Ecole Normale S<rpeneure de Cach411 v"U. Crucis, N.C. 61, avenue du Pr.~j~'>Ut WiJso~ 94235 Cacllan Cedex, ::'C3nce Jolm Lewis Gaddis Yale Universit}' h<mtlJletor MUitary HL'mry and 10'" CenJury Sllldie" lIt Robin HiRbam Contents KaIUa.r Stare Universjly which su!'prt. Kansas Sl.ll1e Uni ....ersity the WWTSA's w-'bs;te ":1 the !nero.. at the following ~ljjrlrcs:;: (URL;: Richa.il E. Kaun www.k··stare.eDu/his.tD.-y/instltu..:..; (luive,.,,)' of North Carolw. -

ADC and Antibomber Defense, 1946-1972

Obtained and posted by AltGov2: www.altgov2.org ADC HISTORICAL STUDY NO. 39 THE AEROSPACE DEFENSE COMMAND AND ANTIBOMBER DEFENSE 194& -1972 ADCHO 73-8-17 FOREWORD" The resources made available to the Aerospace Defense Command (and the predecessor Air Defense Command) for defense against the manned bomber have ebbed and flowed with changes in national military policy. It is often difficult to outline the shape of national policy, however, in a dynamic society like that of the United States. Who makes national policy? Nobody, really. The armed forces make recommenda tions, but these are rarely accepted, in total, by the political administration that makes the final pbrposals to Congress. The changes introduced at the top executive level are variously motivated. The world political climate must be considered, as must various political realities within the country. Cost is always a factor and a determination must be made as to the allocation of funds for defense as opposed to allocations to other government concerns. The personalities, prejudices and predilections of the men who occupy high political office invariably affect proposals to Congress. The disposition of these proposals, of course, is in the hands of Congress. While the executive branch of the government is pushect' and pulled in various directions, Congress is probably subject to heavier pressures. Here, again, the nature of the men who occupy responsible positions within the Congress often affect the decisions of Congress. ·National policy, then, is the product of many minds and is shaped by many diverse interests. The present work is a recapitulation and summarization of three earlier monographs on this subject covering the periods 1946-1950 (ADC Historical Study No. -

Caricature, Satire, Comics Image on Cover: 4

Caricature, Satire, Comics Image on cover: 4. (Armenian Satirical Journal, Critical of Ottoman Tur- key) - Yeritsian, A. and A. Atanasian, editors. Խաթաբալա, e.g. Khatabala [Trouble], complete runs for 1907 (nos. 1-50) and 1912 (nos. 1-50). Image on back cover: 6. (Australian Counterculture) - Oz. No. 1 (April 1963) through No. 41 (February 1969) (all published). Berne Penka Rare Books has been serving the needs of librarians, curators and collectors of rare, unusual and scholarly books on art, architecture and related fields for more than 75 years. We stock an ever-changing inventory of difficult to source books, serials, print porolios, photographic albums, maps, guides, trade catalogs, architectural archives and other materials from anquity to contemporary art. For an up-to-date selecon of new and notable acquisions, please visit our blog at www.rectoversoblog.com or contact us to schedule an appointment at your instuon. And if you should you hap- pen to be in Boston, please give us a call or simply drop by the shop. We welcome visitors. Items in catalog subject to prior sale. Please call or email with inquiries. 1. (A Key Jugendstil Periodical) - Meyrink, Gustav, editor. Der Liebe Au- gustin. Vol. I, nos. 1 through 24 (1904) (all published). Vienna: Herausgeg- eben von der Österreichischen Verlags-Anstalt F. & O. Greipel, 1904. A com- plete run (altogether 411 [1] pp., continuous pagination) of the rare and very important Art Nouveau periodical primarily published under the editorial di- rection of Gustav Meyrink, with artistic and literary contributions by many noted international turn-of-the-century cultural figures, profusely illustrated throughout after cartoons, caricatures, and other drawings by Heinrich Zille, Josef Hoffmann, Julius Klinger, Lutz Ehrenberger, Jules Pascin, Koloman Moser, Emil Orlik, and Alfred Kubin, among many others. -

Rephotography and Urban Materiality

Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, Media City: Spectacular, Ordinary and Contested Spaces (2015), 111-124 1646-5954/ERC123483/2015 111 Of time and the city: Urban rephotography and the memory of war László Munteán* *Assistant professor, Department of Literary and Cultural Studies, Radboud University Nijmegen, the Netherlands ([email protected]) Abstract The increasing public interest in the urban past has recently gained expression in a new genre of photography which consists of an old photograph superimposed over a new one in such a way as to capture exactly the same physical setting at a later point in time. The trend is called rephotography and it finds its roots in geographical surveys designed to show changes in an environment. With easy access to image editing software rephotography enjoys great popularity on a wide array of Internet sites. It has the capacity to invest the most mundane locations with a ghostly aura as we recognize corresponding objects in the new photo as evidence of the event shown in the old photo. My goal in this article is twofold. First, I will put forward the notion of indexicality as a performance, rather than merely an ontological quality, to account for these images’ appeal as traces of the past, despite their obvious use of digital manipulation. Second, through two case studies of war-torn cities, Jo Teeuwisse’s rephotography of Cherbourg and Peter Macdiarmid’s project on Arras, I will examine techniques of superimposition and the affective engagements with the urban past that they generate. Finally, I will explore rephotography’s close kinship with the StreetMuseum, an augmented reality application, which matches historic photographs of London with present-day locations providing an embodied experience of the temporal layers of the city. -

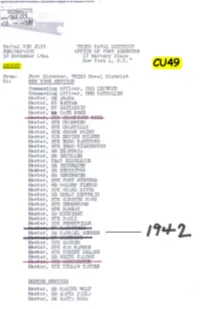

Ss Exchw~Uer

Reproduced from tfti'UnCfassifled l DeclasSiffed Hofdlngs of the National Archives . - Serial UStl #150 THIBD l'JAV~t\L DISTRICT FGR: 1~1.AP :.CCC OFFICl! OF PORT DIRECTOR 30 November 1944 17 Battery Place ?Iew York 4; lI.Y. • SECRET CU49 From.: Port Director, THmD Naval District To: Nmv YORK SECTION . Commanding Officer; USS LEJEUNE , Commanding Officer, ID!S PATRCLLER J;fa ste·r, SS ..1R.A\V' 1l iiaster, liV BA?fr.AM Ma st er, lW BRIT.i\ltt~IC }~asterf SS CAPE NOllf.E , li&itQiPj g'iH( S&!\MPIQMS iEIII, Master; STK CH1Thll>OEG ),faster, STIC CHi\NTITJ.y !.(aster, STK CRO\VN POINT l~aster, STK ElllPmE MILNER Master, STK ESSO IL~RTFORD Master; STK :ESSO l"!Ill~Il1GTOI~ )~aster I SS EL~lrrHI_4 }~aster, SS ECCEIJ.F:R Master, USi~T EXCELSIOR Master; SS EXCHW~UER Ma·ater; SS EXHIBITOR ).ia at er ; SS EX?\1IINS'11ER Master; STK FORT STEVENS Master; SS GOLDEN FI~ECE Master; STK GR _,~ ND RIVF.Jt Master; SS GREAT REPUBLIC Ma st er; STK I\J)RSTEti \\T1\l~G }!aster, STIC ICERl{STO\VN Master; STK r.{:\RK.'lY l1aster, SS l[ID!JIGHT Master, STK PAOLI Master; STK l'ERRYVILLE . ' !~aster, SS R1\PH .. \EL sm.n.ms . BOSTOl~ SECTION Mast er , SS l;L\RilIB WOLF Master, ss ·s .. 'ilrrA P.:\UL,\ blaster, SS Si\ ~lT ~ i ROSA : - -. _~ ' .. ... " ·:•. •" . ' . , co1JV·O"¥ cu-4·9 . · · · ---.. -.- __ .... _- -- -"r----------- --------- ---------------- .... ------ ------ cor.'1Tvt4.NDI1JG OFFICER VESSEL FLAG MAsTER , \. SS AR1'l\"lA BRIT. T. v. ROBERTS r~w BAI\TTA~~~ lJETfI.