Polo-Like Kinase 3 Is Required for Entry Into S Phase

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Subtype and Pathway Specific Responses to Anticancer Compounds in Breast Cancer

Subtype and pathway specific responses to anticancer SPECIAL FEATURE compounds in breast cancer Laura M. Heisera,1, Anguraj Sadanandama,1,2, Wen-Lin Kuoa, Stephen C. Benzb, Theodore C. Goldsteinb, Sam Ngb, William J. Gibba, Nicholas J. Wanga,Safiyyah Ziyada, Frances Tongc, Nora Bayania, Zhi Hua, Jessica I. Billiga, Andrea Duereggera, Sophia Lewisa, Lakshmi Jakkulaa, James E. Korkolaa, Steffen Durincka, François Pepina, Yinghui Guana, Elizabeth Purdomc, Pierre Neuvialc,3, Henrik Bengtssonc,4, Kenneth W. Woodd, Peter G. Smithe, FEATURE Lyubomir T. Vassilevf, Bryan T. Hennessyg, Joel Greshockh, Kurtis E. Bachmanh, Mary Ann Hardwickeh, John W. Parki, Laurence J. Martonj, Denise M. Wolfa, Eric A. Collissoni, Richard M. Nevea, Gordon B. Millsg, Terence P. Speedc,k, BREAST CANCER SPECIAL Heidi S. Feilera, Richard F. Woosterh, David Hausslerb,l, Joshua M. Stuartb, Joe W. Graya,5,6, and Paul T. Spellmana,6,7 aLife Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720; bDepartment of Biomolecular Engineering and Center for Biomolecular Science and Engineering, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 94720; cDepartment of Statistics, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; dCytokinetics, Inc., South San Francisco, CA 94080; eOncology, Millenium Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA 02139; fHoffman-La Roche, Nutley, NJ 07110; gDepartment of Sytems Biology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX 77054; hGlaxoSmithKline, Collegeville, PA 19426; iDivision of Hematology-Oncology, University of California, San Francisco, CA 94143; -

ERCC6L Promotes Cell Growth and Invasion in Human Colorectal Cancer

ONCOLOGY LETTERS 18: 237-246, 2019 ERCC6L promotes cell growth and invasion in human colorectal cancer YANG XIE1,2, JUN YU1,2, FENG WANG1,2, MENGYING LI1,2, XIAO QIU1,2, YUTING LIU1,2 and JIAN QI1,2 1Department of Gastroenterology, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University; 2Hubei Clinical Center and Key Laboratory of Intestinal and Colorectal Diseases, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, Hubei 430071, P.R. China Received March 19, 2018; Accepted April 4, 2019 DOI: 10.3892/ol.2019.10297 Abstract. Excision repair cross-complementation group 6 Introduction like (ERCC6L), a recently discovered DNA helicase, has been demonstrated to be highly expressed in a variety of Tumors are the second leading cause of mortality worldwide, human cancer types. However, the precise role of ERCC6L behind cardiovascular disease (1,2). In the USA, the incidence in colorectal cancer (CRC) remains unclear. The current and mortality rates of colorectal cancer (CRC) are the third study aimed to investigate the potential role of ERCC6L in highest among all cancer types in both males and females the development and progression of CRC. Reverse transcrip- in 2018 (2). In China, CRC ranks as the fifth most common tion-quantitative polymerase chain reaction, western blot malignancy in males and the fourth most common malig- analysis and immunohistochemistry were used to detect the nancy in females, with 12,000 new cases being diagnosed expression level of ERCC6L in 30 matched pairs of CRC and each year (3). Early prevention, detection and treatment are adjacent noncancerous tissues. The function of ERCC6L in cell crucial for cancer control and management. -

Androgen Receptor

RALTITREXED Dihydrofolate reductase BORTEZOMIB IsocitrateCannabinoid dehydrogenase CB1EPIRUBICIN receptor HYDROCHLORIDE [NADP] cytoplasmic VINCRISTINE SULFATE Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha DOXORUBICINAtaxin-2 HYDROCHLORIDENIFENAZONEFOLIC ACID PYRIMETHAMINECellular tumor antigen p53 Muscleblind-likeThyroidVINBURNINEVINBLASTINETRIFLURIDINE protein stimulating 1 DEQUALINIUM SULFATEhormone receptor CHLORIDE Menin/Histone-lysine N-methyltransferasePHENELZINE MLLLANATOSIDE SULFATE C MELATONINDAUNORUBICINBETAMETHASONEGlucagon-like HYDROCHLORIDEEndonuclease peptide 4 1 receptor NICLOSAMIDEDIGITOXINIRINOTECAN HYDROCHLORIDE HYDRATE BISACODYL METHOTREXATEPaired boxAZITHROMYCIN protein Pax-8 ATPase family AAA domain-containing proteinLIPOIC 5 ACID, ALPHA Nuclear receptorCLADRIBINEDIGOXIN ROR-gammaTRIAMTERENE CARMUSTINEEndoplasmic reticulum-associatedFLUOROURACIL amyloid beta-peptide-binding protein OXYPHENBUTAZONEORLISTAT IDARUBICIN HYDROCHLORIDE 6-phospho-1-fructokinaseHeat shockSIMVASTATIN protein beta-1 TOPOTECAN HYDROCHLORIDE AZACITIDINEBloom syndromeNITAZOXANIDE protein Huntingtin Human immunodeficiency virus typeTIPRANAVIR 1 protease VitaminCOLCHICINE D receptorVITAMIN E FLOXURIDINE TAR DNA-binding protein 43 BROMOCRIPTINE MESYLATEPACLITAXEL CARFILZOMIBAnthrax lethalFlap factorendonucleasePrelamin-A/C 1 CYTARABINE Vasopressin V2 receptor AMITRIPTYLINEMicrotubule-associated HYDROCHLORIDERetinoidTRIMETHOPRIM proteinMothers X receptor tau against alpha decapentaplegic homolog 3 Histone-lysine N-methyltransferase-PODOFILOX H3 lysine-9OXYQUINOLINE -

Inhibition of ERK 1/2 Kinases Prevents Tendon Matrix Breakdown Ulrich Blache1,2,3, Stefania L

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Inhibition of ERK 1/2 kinases prevents tendon matrix breakdown Ulrich Blache1,2,3, Stefania L. Wunderli1,2,3, Amro A. Hussien1,2, Tino Stauber1,2, Gabriel Flückiger1,2, Maja Bollhalder1,2, Barbara Niederöst1,2, Sandro F. Fucentese1 & Jess G. Snedeker1,2* Tendon extracellular matrix (ECM) mechanical unloading results in tissue degradation and breakdown, with niche-dependent cellular stress directing proteolytic degradation of tendon. Here, we show that the extracellular-signal regulated kinase (ERK) pathway is central in tendon degradation of load-deprived tissue explants. We show that ERK 1/2 are highly phosphorylated in mechanically unloaded tendon fascicles in a vascular niche-dependent manner. Pharmacological inhibition of ERK 1/2 abolishes the induction of ECM catabolic gene expression (MMPs) and fully prevents loss of mechanical properties. Moreover, ERK 1/2 inhibition in unloaded tendon fascicles suppresses features of pathological tissue remodeling such as collagen type 3 matrix switch and the induction of the pro-fbrotic cytokine interleukin 11. This work demonstrates ERK signaling as a central checkpoint to trigger tendon matrix degradation and remodeling using load-deprived tissue explants. Tendon is a musculoskeletal tissue that transmits muscle force to bone. To accomplish its biomechanical function, tendon tissues adopt a specialized extracellular matrix (ECM) structure1. Te load-bearing tendon compart- ment consists of highly aligned collagen-rich fascicles that are interspersed with tendon stromal cells. Tendon is a mechanosensitive tissue whereby physiological mechanical loading is vital for maintaining tendon archi- tecture and homeostasis2. Mechanical unloading of the tissue, for instance following tendon rupture or more localized micro trauma, leads to proteolytic breakdown of the tissue with severe deterioration of both structural and mechanical properties3–5. -

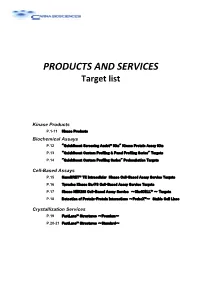

PRODUCTS and SERVICES Target List

PRODUCTS AND SERVICES Target list Kinase Products P.1-11 Kinase Products Biochemical Assays P.12 "QuickScout Screening Assist™ Kits" Kinase Protein Assay Kits P.13 "QuickScout Custom Profiling & Panel Profiling Series" Targets P.14 "QuickScout Custom Profiling Series" Preincubation Targets Cell-Based Assays P.15 NanoBRET™ TE Intracellular Kinase Cell-Based Assay Service Targets P.16 Tyrosine Kinase Ba/F3 Cell-Based Assay Service Targets P.17 Kinase HEK293 Cell-Based Assay Service ~ClariCELL™ ~ Targets P.18 Detection of Protein-Protein Interactions ~ProbeX™~ Stable Cell Lines Crystallization Services P.19 FastLane™ Structures ~Premium~ P.20-21 FastLane™ Structures ~Standard~ Kinase Products For details of products, please see "PRODUCTS AND SERVICES" on page 1~3. Tyrosine Kinases Note: Please contact us for availability or further information. Information may be changed without notice. Expression Protein Kinase Tag Carna Product Name Catalog No. Construct Sequence Accession Number Tag Location System HIS ABL(ABL1) 08-001 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) BTN BTN-ABL(ABL1) 08-401-20N Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal DYKDDDDK Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) [E255K] HIS ABL(ABL1)[E255K] 08-094 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) HIS ABL(ABL1)[T315I] 08-093 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) [T315I] BTN BTN-ABL(ABL1)[T315I] 08-493-20N Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal DYKDDDDK Insect (sf21) ACK(TNK2) GST ACK(TNK2) 08-196 Catalytic domain -

The Role of Plk3 in Oncogenesis

Oncogene (2016) 35, 135–147 © 2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-9232/16 www.nature.com/onc REVIEW The role of Plk3 in oncogenesis C Helmke1, S Becker1 and K Strebhardt1,2 The polo-like kinases (Plks) encompass a family of five serine/threonine protein kinases that play essential roles in many cellular processes involved in the control of the cell cycle, including entry into mitosis, DNA replication and the response to different types of stress. Plk1, which has been validated as a cancer target, came into the focus of many pharmaceutical companies for the development of small-molecule inhibitors as anticancer agents. Recently, FDA (Food and Drug Administration) has granted a breakthrough therapy designation to the Plk inhibitor BI 6727 (volasertib), which provided a survival benefit for patients suffering from acute myeloid leukemia. However, the various ATP-competitive inhibitors of Plk1 that are currently in clinical development also inhibit the activities of Plk2 and Plk3, which are considered as tumor suppressors. Plk3 contributes to the control and progression of the cell cycle while acting as a mediator of apoptosis and various types of cellular stress. The aberrant expression of Plk3 was found in different types of tumors. Recent progress has improved our understanding of Plk3 in regulating stress signaling and tumorigenesis. When using ATP-competitive Plk1 inhibitors, the biological roles of Plk1-related family members like Plk3 in cancer cells need to be considered carefully to improve treatment strategies -

The Pyrazolyl-Urea Gege3 Inhibits Tumor Angiogenesis and Reveals Dystrophia Myotonica Protein Kinase (DMPK)1 As a Novel Angiogenesis Target

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, 2017, Vol. 8, (No. 64), pp: 108195-108212 Research Paper The pyrazolyl-urea GeGe3 inhibits tumor angiogenesis and reveals dystrophia myotonica protein kinase (DMPK)1 as a novel angiogenesis target Elda Meta1, Beat A. Imhof2, Patricia Ropraz2, Richard J. Fish3, Chiara Brullo1, Olga Bruno1 and Adama Sidibé2 1Department of Pharmacy, Medicinal Chemistry Section, University of Genoa, 16132 Genoa, Italy 2Department of Pathology and Immunology, University of Geneva, 1211 Genève, Switzerland 3Department of Genetic Medicine and Development, University of Geneva, 1211 Genève, Switzerland Correspondence to: Adama Sidibé, email: [email protected] Keywords: angiogenesis; novel target; pyrazolyl-urea; kinase inhibitors; DMPK Received: May 04, 2017 Accepted: July 26, 2017 Published: November 21, 2017 Copyright: Meta et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC BY 3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT The limitation of targeting VEGF/VEGFR2 signalling to stop angiogenesis in cancer therapy has been blamed on re-activation of alternative receptor tyrosine kinases by compensatory angiogenic factors. Targeting MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways in endothelial cells may be an alternative or complementary approach. Herein we aimed to evaluate the antitumor and antiangiogenic potential of a novel pyrazolyl-urea kinase inhibitor, GeGe3, and to identify its kinase targets. We found GeGe3 to inhibit the proliferation of HUVEC and endothelial tube formation. GeGe3 impaired inter-segmental angiogenesis during development of zebrafish embryos. In mice, GeGe3 blocked angiogenesis and tumor growth in transplanted subcutaneous Lewis Lung Carcinomas. -

Lestaurtinib

LESTAURTINIB MIDOSTAURIN AXITINIB Tyrosine-protein kinase TIE-2 Serine/threonine-protein kinase 2Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 5 Serine/threonine-protein kinase MST2 NERATINIB SPS1/STE20-related protein kinase YSK4 SORAFENIB Dual specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 5 Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase MER Platelet-derivedTANDUTINIB growth factor receptor beta Epithelial discoidin domain-containing receptor 1 NINTEDANIB Mixed lineage kinase 7 Macrophage colonyTyrosine-protein stimulating kinasefactor receptorreceptor UFOTyrosine-protein kinase BLK Tyrosine-protein kinase LCK NILOTINIB Serine/threonine-protein kinase 10 NT-3 growth factor receptor DiscoidinMitogen-activated domain-containing protein receptor kinase 2 kinase kinase kinase 3 Tyrosine-protein kinase ABL Nerve growth factor receptor Trk-A FORETINIBEphrin type-B receptor 6 Adaptor-associated kinaseQUIZARTINIB Ephrin type-AEphrin receptor type-B receptor5 2 Mitogen-activated proteinTyrosine-protein kinase kinase kinaseTyrosine-protein kinase JAK3 kinase 2 kinase receptor FLT3 Fibroblast growth factorSerine/threonine-protein receptor 1 kinase Aurora-B Ephrin type-A receptor 8 Serine/threonine-proteinDual specificty protein kinase kinase PLK4Mitogen-activated CLK1 protein kinase kinase kinase 12 Misshapen-like kinase 1Cyclin-dependent kinase-like 2 Platelet-derivedLINIFANIB growth factor receptorEphrin alpha type-A receptor 4 c-Jun N-terminal kinaseALISERTIB 3 Serine/threonine-protein kinase SIK1 PONATINIB Dual specificity protein kinaseStem -

Specific Inhibition of HIF Activity

cancers Review Specific Inhibition of HIF Activity: Can Peptides Lead the Way? Ilias Mylonis 1,* , Georgia Chachami 1 and George Simos 1,2,* 1 Laboratory of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Thessaly, 41500 Larissa, Greece; [email protected] 2 Gerald Bronfman Department of Oncology, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, QC H4A 3T2, Canada * Correspondence: [email protected] (I.M.); [email protected] (G.S.) Simple Summary: Cancer cells in solid tumors often experience lack of oxygen (hypoxia), which they overcome with the help of hypoxia inducible transcription factors (HIFs). When HIFs are activated, they stimulate the expression of many genes and cause the production of proteins that help cancer cells grow and migrate even in the presence of very little oxygen. Many experiments have shown that agents that block the activity of HIFs (HIF inhibitors) can prevent growth of cancer cells under hypoxia and, subsequently, hinder formation of malignant tumors or metastases. Most small chem- ical HIF inhibitors lack the selectivity required for development of safe anticancer drugs. On the other hand, peptides derived from HIFs themselves can be very selective HIF inhibitors by dis- rupting specific associations of HIFs with cellular components that are essential for HIF activation. This review discusses the nature of available peptide HIF inhibitors and their prospects as effective pharmaceuticals against cancer. Abstract: Reduced oxygen availability (hypoxia) is a characteristic of many disorders including cancer. Central components of the systemic and cellular response to hypoxia are the Hypoxia Inducible Factors (HIFs), a small family of heterodimeric transcription factors that directly or indirectly regulate the expression of hundreds of genes, the products of which mediate adaptive changes in processes that Citation: Mylonis, I.; Chachami, G.; include metabolism, erythropoiesis, and angiogenesis. -

Discovery of Potent and Selective MRCK Inhibitors with Therapeutic

Published OnlineFirst January 30, 2018; DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2870 Cancer Translational Science Research Discovery of Potent and Selective MRCK Inhibitors with Therapeutic Effect on Skin Cancer Mathieu Unbekandt1, Simone Belshaw2, Justin Bower2, Maeve Clarke2, Jacqueline Cordes2, Diane Crighton2, Daniel R. Croft2, Martin J. Drysdale2, Mathew J. Garnett3, Kathryn Gill2, Christopher Gray2, David A. Greenhalgh4, James A.M. Hall3, Jennifer Konczal2, Sergio Lilla5, Duncan McArthur2, Patricia McConnell2, Laura McDonald2, Lynn McGarry6, Heather McKinnon2, Carol McMenemy4, Mokdad Mezna2, Nicolas A. Morrice5, June Munro1, Gregory Naylor1, Nicola Rath1, Alexander W. Schuttelkopf€ 2, Mairi Sime2, and Michael F. Olson1,7 Abstract The myotonic dystrophy–related Cdc42-binding kinases an autophosphorylation site, enabling development of a phos- MRCKa and MRCKb contribute to the regulation of actin–myosin phorylation-sensitive antibody tool to report on MRCKa status in cytoskeleton organization and dynamics, acting in concert with tumor specimens. In a two-stage chemical carcinogenesis model the Rho-associated coiled-coil kinases ROCK1 and ROCK2. The of murine squamous cell carcinoma, topical treatments reduced absence of highly potent and selective MRCK inhibitors has MRCKa S1003 autophosphorylation and skin papilloma out- resulted in relatively little knowledge of the potential roles of growth. In parallel work, we validated a phospho-selective anti- these kinases in cancer. Here, we report the discovery of the body with the capability to monitor drug pharmacodynamics. azaindole compounds BDP8900 and BDP9066 as potent and Taken together, our findings establish an important oncogenic selective MRCK inhibitors that reduce substrate phosphorylation, role for MRCK in cancer, and they offer an initial preclinical proof leading to morphologic changes in cancer cells along with inhi- of concept for MRCK inhibition as a valid therapeutic strategy. -

Supplement Materials Table S1. the Top15 Terms for Genetic Association

Supplement materials Table S1. The top15 terms for genetic association database. Term Count Percentage % p-Value List FDR Lung Cancer 73 25.34 6.70E-36 271 1.16E-32 Breast Cancer 67 23.26 2.92E-30 271 5.06E-27 Bladder Cancer 60 20.83 3.33E-27 271 5.78E-24 Esophageal adenocarcinoma 52 18.06 6.24E-29 271 1.08E-25 Colorectal Cancer 51 17.71 4.99E-24 271 8.66E-21 Prostate cancer 42 14.58 7.12E-14 271 1.23E-10 Ovarian cancer 39 13.54 2.04E-16 271 3.89E-13 Pancreatic Neoplasms 20 6.94 1.45E-08 271 2.52E-05 Thyroid cancer 19 6.59 9.98E-11 271 1.73E-07 Rheumatoid arthritis 19 6.60 8.82E-08 271 1.53E-04 Neoplasms 17 5.90 4.58E-08 271 7.94E-05 Stomach cancer 16 5.56 1.17E-09 271 2.03E-06 Head and neck cancer 15 5.21 5.23E-09 271 9.07E-06 Stomach Neoplasms 14 4.86 6.20E-07 271 1.08E-3 Leukemia 14 4.86 1.02E-06 271 1.78 E-3 Table S2. The results of the reverse docking for AutoDock Vina. PDB Protein Gene_Name Uniprot_ID Score 4TVJ Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 2 PARP2 Q9UGN5 -10.80 2DQ7 Proto-oncogene tyrosine-protein kinase Fyn FYN P06241 -10.00 4KIK Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase IKBKB O14920 -10.00 subunit beta 3EQR Activated CDC42 kinase 1 ACK1/TNK2 Q07912 -9.90 3MTF Activin receptor type-1 ACVR1 Q04771 -9.90 4GV0 Poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase 3 PARP3 Q9Y6F1 -9.90 1M6I Programmed cell death protein 8 AIF O95831 -9.80 1UA2 Cell division protein kinase 7 CDK7 P50613 -9.80 1Z6T Apoptotic protease activating factor 1 APAF1 O14727 -9.80 1ZXM DNA topoisomerase II TOPII P11388 -9.80 2WOU Serine/Threonine-protein kinase NEK7 NEK7 Q8TDX7 -9.60 -

Online Supplement to Gene Expression Pathways Across

Online supplement to Gene Expression Pathways across Multiple Tissues in Antineutrophil Cytoplasmic Antibody-associated Vasculitis Reveal Core Pathways of Disease Pathology, The Journal of Rheumatology, doi:10.3899/jrheum.180455 Supplement A. Local false discovery rate (locfdr) in one dimension A local false discovery rate (locfdr) is defined from a mixture of distributions. Suppose that we have k tests each with p-value pi, for i = 1, 2, … , k. Let z be the test statistic of interest (pathways in the manuscript). Each case (or test) can be considered from either null (H0) or alternative (H1) with the prior probabilities of p0 = probability(H0) and p1 = probability(H1) = 1 – p0. Then, z values have the following mixture density f(z) = p0f0(z) + p1f1(z), where f0(z) and f1(z) are the null and alternative densities, respectively. Then, the locfdr is defined as locfdr(z) = probability{H0 | Z=z}, where Z is a test statistic. Under the mixture model above, it is straightforward to show (S1, S2) locfdr(z) = p0 f0(z) / f(z). There can be several different choices of f0 and f1, and ways to estimate them. In our approach, f0 is a normal distribution and f1 is a log-concave density function. Then, we estimate p0, f0 and f1 by the EM algorithm that is most widely used to estimate a mixture density. The above is the description of one-dimensional case and the technical report (S1) presents the extension to multi-dimensional cases and simulation studies to show how well our approach can estimate locfdr under various settings and performs better than other existing methods.