Hipólito Irigoyen's Second Administration: a Study in Administrative Collapse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Thesis Comes Within Category D

* SHL ITEM BARCODE 19 1721901 5 REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree Year i ^Loo 0 Name of Author COPYRIGHT This Is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London, it is an unpubfished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the .premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962 -1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 -1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. -

La Congruencia Aliancista De Los Partidos Argentinos En Elecciones Concurrentes (1983- 2011) Estudios Políticos, Vol

Estudios Políticos ISSN: 0185-1616 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México Cleric, Paula La congruencia aliancista de los partidos argentinos en elecciones concurrentes (1983- 2011) Estudios Políticos, vol. 9, núm. 36, septiembre-diciembre, 2015, pp. 143-170 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=426441558007 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto La congruencia aliancista de los partidos argentinos en elecciones concurrentes (1983 -2011) Paula Clerici* Resumen El presente artículo ofrece un estudio sobre la congruencia de las alianzas electorales en Argen- tina entre 1983 y 2011. Lo anterior a partir de dos acciones: primero, ubicando empíricamente el fenómeno; segundo, conociendo el nivel de congruencia que los partidos han tenido en su política aliancista en los distintos procesos electorales que se presentaron durante el período considerado. La propuesta dedica un apartado especial al Partido Justicialista (PJ) y a la Unión Cívica Radical (UCR), por su importancia sistémica. Palabras clave: alianzas partidistas, partidos políticos, congruencia aliancista, procesos electorales, .Argentina. Abstract This article presents a study on the consistency of the electoral alliances in Argentina between 1983 and 2011. From two actions: first, locating empirically the phenomenon; and second, knowing the level of consistency that the parties have had in their alliance policy in the different electoral processes that occurred during the period. -

Figure A1 General Elections in Argentina, 1995-2019 Figure A2 Vote for Peronists Among Highest-Educated and Top-Income Voters In

Chapter 15. "Social Inequalities, Identity, and the Structure of Political Cleavages in Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru, 1952-2019" Oscar BARRERA, Ana LEIVA, Clara MARTÍNEZ-TOLEDANO, Álvaro ZÚÑIGA-CORDERO Appendix A - Argentina Main figures and tables Figure A1 General elections in Argentina, 1995-2019 Figure A2 Vote for Peronists among highest-educated and top-income voters in Argentina, after controls Table A1 The structure of political cleavages in Argentina, 2015-2019 Appendix Figures - Structure of the Vote for Peronists Figure AA1 Vote for Peronists by income decile in Argentina Figure AA2 Vote for Peronists by income group in Argentina Figure AA3 Vote for Peronists by education level in Argentina Figure AA4 Vote for Peronists by age group in Argentina Figure AA5 Vote for Peronists by gender in Argentina Figure AA6 Vote for Peronists by marital status in Argentina Figure AA7 Vote for Peronists by employment status in Argentina Figure AA8 Vote for Peronists by employment sector in Argentina Figure AA9 Vote for Peronists by self-employment status in Argentina Figure AA10 Vote for Peronists by occupation in Argentina Figure AA11 Vote for Peronists by subjective social class in Argentina Figure AA12 Vote for Peronists by rural-urban location in Argentina Figure AA13 Vote for Peronists by region in Argentina Figure AA14 Vote for Peronists by ethnicity in Argentina Figure AA15 Vote for Peronists by religious affiliation in Argentina Figure AA16 Vote for Peronists by religiosity in Argentina Figure AA17 Vote for -

The Transformation of Party-Union Linkages in Argentine Peronism, 1983–1999*

FROM LABOR POLITICS TO MACHINE POLITICS: The Transformation of Party-Union Linkages in Argentine Peronism, 1983–1999* Steven Levitsky Harvard University Abstract: The Argentine (Peronist) Justicialista Party (PJ)** underwent a far- reaching coalitional transformation during the 1980s and 1990s. Party reformers dismantled Peronism’s traditional mechanisms of labor participation, and clientelist networks replaced unions as the primary linkage to the working and lower classes. By the early 1990s, the PJ had transformed from a labor-dominated party into a machine party in which unions were relatively marginal actors. This process of de-unionization was critical to the PJ’s electoral and policy success during the presidency of Carlos Menem (1989–99). The erosion of union influ- ence facilitated efforts to attract middle-class votes and eliminated a key source of internal opposition to the government’s economic reforms. At the same time, the consolidation of clientelist networks helped the PJ maintain its traditional work- ing- and lower-class base in a context of economic crisis and neoliberal reform. This article argues that Peronism’s radical de-unionization was facilitated by the weakly institutionalized nature of its traditional party-union linkage. Although unions dominated the PJ in the early 1980s, the rules of the game governing their participation were always informal, fluid, and contested, leaving them vulner- able to internal changes in the distribution of power. Such a change occurred during the 1980s, when office-holding politicians used patronage resources to challenge labor’s privileged position in the party. When these politicians gained control of the party in 1987, Peronism’s weakly institutionalized mechanisms of union participation collapsed, paving the way for the consolidation of machine politics—and a steep decline in union influence—during the 1990s. -

Civil Liberties: 2 Aggregate Score: 83 Freedom Rating: 2.0 Overview

Argentina Page 1 of 8 Published on Freedom House (https://freedomhouse.org) Home > Argentina Argentina Country: Argentina Year: 2018 Freedom Status: Free Political Rights: 2 Civil Liberties: 2 Aggregate Score: 83 Freedom Rating: 2.0 Overview: Argentina is a vibrant representative democracy, with competitive elections and lively public debate. Corruption and drug-related violence are among the country’s most serious challenges. Political Rights and Civil Liberties: POLITICAL RIGHTS: 33 / 40 A. ELECTORAL PROCESS: 11 / 12 A1. Was the current head of government or other chief national authority elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 The constitution provides for a president to be elected for a four-year term, with the option of reelection for one additional term. Presidential candidates must win 45 percent of the vote to avoid a runoff. Mauricio Macri was elected president in 2015 in a poll deemed competitive and credible by international observers. A2. Were the current national legislative representatives elected through free and fair elections? 4 / 4 https://freedomhouse.org/print/49941 9/14/2018 Argentina Page 2 of 8 The National Congress consists of a 257-member the Chamber of Deputies, whose representatives are directly elected for four-year terms with half of the seats up for election every two years; and the 72-member Senate, whose representatives are directly elected for six-year terms, with one third of the seats up for election every two years. Legislators are elected through a proportional representation system with a closed party list. Legislative elections, including the most recent held in October 2017, are generally free and fair. -

Argentina: from Kirchner to Kirchner

ArgentinA: From Kirchner to Kirchner Steven Levitsky and María Victoria Murillo Steven Levitsky is professor of government at Harvard University. María Victoria Murillo is associate professor of political science and international affairs at Columbia University. Together they edited Ar- gentine Democracy: The Politics of Institutional Weakness (2005). Argentina’s 28 October 2007 presidential election contrasted sharply with the one that preceded it. The 2003 race took place in the after- math of an unprecedented economic collapse and the massive December 2001 protests that toppled two presidents in a span of ten days. That election—which was won by little-known (Peronist) Justicialist Party governor Néstor Kirchner—was held in a climate of political fragmenta- tion and uncertainty. Little uncertainty surrounded the 2007 campaign. After four years of strong economic growth, and with the opposition in shambles, a victory by the incumbent Peronists was a foregone conclu- sion. The only surprise was that Kirchner, who remained popular, chose not to seek reelection. Instead, his wife, Senator Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, ran in his place. Cristina Kirchner captured 45 percent of the vote, easily defeating Elisa Carrió of the left-of-center Civic Coalition (23 percent) and Kirch- ner’s former economics minister, Roberto Lavagna (17 percent), who was backed by the Radical Civic Union (UCR). In addition to winning more than three-quarters of Argentina’s 23 governorships, the Justicial- ist Party (PJ) and other pro-Kirchner allies won large majorities in both legislative chambers. In the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of Argentina’s bicameral National Congress, progovernment Peronists and other Kirchner allies (including pro-Kirchner Radicals) won 160 of 257 seats, while dissident Peronists won another 10 seats. -

Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012

Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 1 Module 4: Macro Report Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Module 4: Macro Report September 10, 2012 Country: Argentina Date of Election: October 25, 2015 Prepared by: Noam Lupu, Carlos Gervasoni, Virginia Oliveros, and Luis Schiumerini Date of Preparation: December 2016 NOTES TO COLLABORATORS: . The information provided in this report contributes to an important part of the CSES project. The information may be filled out by yourself, or by an expert or experts of your choice. Your efforts in providing these data are greatly appreciated! Any supplementary documents that you can provide (e.g., electoral legislation, party manifestos, electoral commission reports, media reports) are also appreciated, and may be made available on the CSES website. Answers should be as of the date of the election being studied. Where brackets [ ] appear, collaborators should answer by placing an “X” within the appropriate bracket or brackets. For example: [X] . If more space is needed to answer any question, please lengthen the document as necessary. Data Pertinent to the Election at which the Module was Administered 1a. Type of Election [ ] Parliamentary/Legislative [X] Parliamentary/Legislative and Presidential [ ] Presidential [ ] Other; please specify: __________ 1b. If the type of election in Question 1a included Parliamentary/Legislative, was the election for the Upper House, Lower House, or both? [ ] Upper House [ ] Lower House [X] Both [ ] Other; please specify: __________ Comparative Study of Electoral Systems 2 Module 4: Macro Report 2a. What was the party of the president prior to the most recent election, regardless of whether the election was presidential? Frente para la Victoria, FPV (Front for Victory)1 2b. -

Social Mobilization and Political Decay in Argentina

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1986 Social Mobilization and Political Decay in Argentina Craig Huntington Melton College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Latin American Studies Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Melton, Craig Huntington, "Social Mobilization and Political Decay in Argentina" (1986). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625361. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-413n-d563 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SOCIAL MOBILIZATION AND POLITICAL DECAY IN ARGENTINA A Thesis Presented to The faculty of the Department of Government The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Craig Huntington Melton 1986 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts raig Huntington Melton Approved, August 19(ff6 Geor, s on Donald J !xter A. David A. Dessler DEDICATIONS To the memory of LEWIS GRAY MYERS a poet always following the sun. Thanks to Darby, Mr. Melding, Rich & Judy, and my parents for their encouragement and kind support. h iii. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page DEDICATION.............................................. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS................................................... V LIST OF T A B L E S ........................................... vi ABSTRACT............................................... -

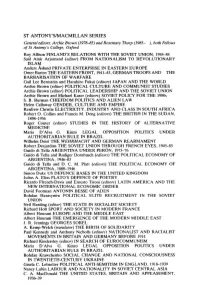

St Antony's/Macmillan Series

ST ANTONY'S/MACMILLAN SERIES General editors: Archie Brown (1978-85) and Rosemary Thorp (1985- ), both Fellows of St Antony's College, Oxford Roy Allison FINLAND'S RELATIONS WITH THE SOVIET UNION, 1944-84 Said Amir Arjomand (editor) FROM NATIONALISM TO REVOLUTIONARY ISLAM Anders Åslund PRIVATE ENTERPRISE IN EASTERN EUROPE Orner Bartov THE EASTERN FRONT, 1941-45, GERMAN TROOPS AND THE BARBARISATION OF WARFARE Gail Lee Bernstein and Haruhiro Fukui (editors) JAPAN AND THE WORLD Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL CULTURE AND COMMUNIST STUDIES Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND THE SOVIET UNION Archie Brown and Michael Kaser (editors) SOVIET POLICY FOR THE 1980s S. B. Burman CHIEFDOM POLITICS AND ALIEN LAW Helen Callaway GENDER, CULTURE AND EMPIRE Renfrew Christie ELECTRICITY, INDUSTRY AND CLASS IN SOUTH AFRICA Robert O. Collins and FrancisM. Deng (editors) THE BRITISH IN THE SUDAN, 1898-1956 Roger Couter (editor) STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE Maria D'Alva G. Kinzo LEGAL OPPOSITION POLITICS UNDER AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN BRAZIL Wilhelm Deist THE WEHRMACHT AND GERMAN REARMAMENT Robert Desjardins THE SOVIET UNION THROUGH FRENCH EYES, 1945-85 Guido di Tella ARGENTINA UNDER PERÓN, 1973-76 Guido di Tella and Rudiger Dornbusch (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1946-83 Guido di Tella and D. C. M. Platt (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1880-1946 Simon Duke US DEFENCE BASES IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Julius A. Elias PLATO'S DEFENCE OF POETRY Ricardo Ffrench-Davis and Ernesto Tironi (editors) LATIN AMERICA AND THE NEW INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC ORDER David Footman ANTONIN BESSE OF ADEN Bohdan Harasymiw POLITICAL ELITE RECRUITMENT IN THE SOVIET UNION Neil Harding (editor) THE STATE IN SOCIALIST SOCIETY Richard Holt SPORT AND SOCIETY IN MODERN FRANCE Albert Hourani EUROPE AND THE MIDDLE EAST Albert Hourani THE EMERGENCE OF THE MODERN MIDDLE EAST J. -

PERONISM and ANTI-PERONISM: SOCIAL-CULTURAL BASES of POLITICAL IDENTITY in ARGENTINA PIERRE OSTIGUY University of California

PERONISM AND ANTI-PERONISM: SOCIAL-CULTURAL BASES OF POLITICAL IDENTITY IN ARGENTINA PIERRE OSTIGUY University of California at Berkeley Department of Political Science 210 Barrows Hall Berkeley, CA 94720 [email protected] Paper presented at the LASA meeting, in Guadalajara, Mexico, on April 18, 1997 This paper is about political identity and the related issue of types of political appeals in the public arena. It thus deals with a central aspect of political behavior, regarding both voters' preferences and identification, and politicians' electoral strategies. Based on the case of Argentina, it shows the at times unsuspected but unmistakable impact of class-cultural, and more precisely, social-cultural differences on political identity and electoral behavior. Arguing that certain political identities are social-culturally based, this paper introduces a non-ideological, but socio-politically significant, axis of political polarization. As observed in the case of Peronism and anti-Peronism in Argentina, social stratification, particularly along an often- used compound, in surveys, of socio-economic status and education,1 is tightly associated with political behavior, but not so much in Left-Right political terms or even in issue terms (e.g. socio- economic platforms or policies), but rather in social-cultural terms, as seen through the modes and type of political appeals, and figuring centrally in certain already constituted political identities. Forms of political appeals may be mapped in terms of a two-dimensional political space, defined by the intersection of this social-cultural axis with the traditional Left-to-Right spectrum. Also, since already constituted political identities have their origins in the successful "hailing"2 of pluri-facetted people and groups, such a bi-dimensional space also maps political identities. -

Argentine Perspectives on the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons CUREJ - College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal College of Arts and Sciences 5-7-2014 In Defense of Our Brothers’ Cause: Argentine Perspectives on the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 Tomas E. Piedrahita University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/curej Part of the Cultural History Commons, European History Commons, Latin American History Commons, Political History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Piedrahita, Tomas E., "In Defense of Our Brothers’ Cause: Argentine Perspectives on the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939" 07 May 2014. CUREJ: College Undergraduate Research Electronic Journal, University of Pennsylvania, https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/187. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/curej/187 For more information, please contact [email protected]. In Defense of Our Brothers’ Cause: Argentine Perspectives on the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 Abstract Long a country of two faces – European and Latin American – Argentina saw the woes of the Spanish Civil War as deeply reflective of their struggles and immensely predictive of their fate. Their preoccupation with the war’s outcome was at once an expression of the country's long-simmering identity crisis and an attempt to affirm its Hispanic otherness, particularly in the wake of the 1930 coup d’état. This article explores the subtleties of this identity crisis with an eye toward determining the motives underlying claims and references to Spain, an exploration which rests primarily on the nexus of social and cultural history and secondarily on their intersection with political history. -

Pensamiento Y Praxis De Rogelio Frigerio, Fundador Del Proyecto Desarrollista En Argentina

García Bossio, Horacio Pensamiento y praxis de Rogelio Frigerio, fundador del proyecto desarrollista en Argentina Tesis de Doctorado en Ciencias Políticas Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Políticas y de la Comunicación Este documento está disponible en la Biblioteca Digital de la Universidad Católica Argentina, repositorio institucional desarrollado por la Biblioteca Central “San Benito Abad”. Su objetivo es difundir y preservar la producción intelectual de la Institución. La Biblioteca posee la autorización del autor para su divulgación en línea. Cómo citar el documento: García Bossio, H. (2012, octubre). Pensamiento y praxis de Rogelio Frigerio, fundador del proyecto desarrollista en Argentina [en línea]. Tesis de Doctorado en Ciencias Políticas, Universidad Católica Argentina, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Políticas y de la Comunicación, Instituto de Ciencias Políticas y Relaciones Internacionales. Disponible en: http://bibliotecadigital.uca.edu.ar/repositorio/tesis/pensamiento-praxis-rogelio-frigerio.pdf [Fecha de consulta: …] Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Políticas y de la Comunicación Tesis Doctoral Pensamiento y praxis de Rogelio Frigerio, fundador del proyecto desarrollista en Argentina Director Doctor Samuel Amaral Licenciado Horacio García Bossio Buenos Aires, Octubre 2012 1 A mis amores María Angélica, María Pilar, Lucía y Juan Pedro 2 Agradecimientos El desafío de encarar una tesis doctoral implica abordar un itinerario colmado de algunos logros evidentes, de esfuerzos no siempre correspondidos