Social Mobilization and Political Decay in Argentina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BBREVE CRONOLOGÍA DE GOLPES DE ESTADO EN EL SIGLO XX Y XXI Equipo Conceptos Y Fenómenos Fundamentales De Nuestro Tiempo

CONCEPTOS Y FENÓMENOS FUNDAMENTALES DE NUESTRO TIEMPO UNAM UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACIONES SOCIALES BBREVE CRONOLOGÍA DE GOLPES DE ESTADO EN EL SIGLO XX Y XXI Equipo Conceptos y Fenómenos Fundamentales de Nuestro Tiempo Noviembre 2019 1 CRONOLOGÍA DE GOLPES DE ESTADO EN EL SIGLO XX Y XXI1 Por Equipo de Conceptos y Fenómenos Fundamentales de Nuestro Tiempo2 Siglo XX: 1908: golpe de Estado en Venezuela. Juan Vicente Gómez derroca a Cipriano Castro. 1911: golpe de Estado cívico-militar en México. Francisco I. Madero y sus fuerzas revolucionarias derrocan al ejército porfirista y obligan a la renuncia de Porfirio Díaz. 1913: golpe de Estado de Victoriano Huerta en México. 1913: golpe de Estado de los Jóvenes Turcos en el Imperio Otomano. 1914: golpe militar en Perú. Óscar R. Benavides derroca a Guillermo Billinghurst. 1917: golpe militar en Costa Rica. Federico Tinoco Granados derroca a Alfredo González Flores. 1917: En Rusia se provocan varios golpes de Estado. En febrero contra los zares, que triunfa. En julio por los bolcheviques contra el gobierno provisional, que fracasa. En agosto por el general Kornilov, que fracasa y en octubre Lenin derriba al gobierno provisional de Kerensky. 1919: golpe de Estado en Perú. Augusto Leguía derroca a José Pardo y Barreda. 1923: fallido golpe de Estado de Adolf Hitler en Alemania. 1923: golpe de Estado de Primo de Rivera en España, el 13 de septiembre. 1924: golpe de Estado en Chile. Se instala una junta de gobierno presidida por Luis Altamirano, que disuelve el Congreso Nacional. 1925: golpe de Estado en Chile, que derrocó a la junta de gobierno presidida por Luis Altamirano. -

Beneath the Surface: Argentine-United States Relations As Perón Assumed the Presidency

Beneath the Surface: Argentine-United States Relations as Perón Assumed the Presidency Vivian Reed June 5, 2009 HST 600 Latin American Seminar Dr. John Rector 1 Juan Domingo Perón was elected President of Argentina on February 24, 1946,1 just as the world was beginning to recover from World War II and experiencing the first traces of the Cold War. The relationship between Argentina and the United States was both strained and uncertain at this time. The newly elected Perón and his controversial wife, Eva, represented Argentina. The United States’ presence in Argentina for the preceding year was primarily presented through Ambassador Spruille Braden.2 These men had vastly differing perspectives and visions for Argentina. The contest between them was indicative of the relationship between the two nations. Beneath the public and well-documented contest between Perón and United States under the leadership of Braden and his successors, there was another player whose presence was almost unnoticed. The impact of this player was subtlety effective in normalizing relations between Argentina and the United States. The player in question was former United States President Herbert Hoover, who paid a visit to Argentina and Perón in June of 1946. This paper will attempt to describe the nature of Argentine-United States relations in mid-1946. Hoover’s mission and insights will be examined. In addition, the impact of his visit will be assessed in light of unfolding events and the subsequent historiography. The most interesting aspect of the historiography is the marked absence of this episode in studies of Perón and Argentina3 even though it involved a former United States President and the relations with 1 Alexander, 53. -

Abstract Department of Political Science Westfield

ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE WESTFIELD, ALWYN W BA. HONORS UNIVERSITY OF ESSEX, 1976 MS. LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON, 1977 THE IMPACT OF LEADERSHIP ON POLITICS AND POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT IN ST VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES UNDER EBENEZER THEODORE JOSHUA AND ROBERT MILTON CATO Committee Chair: Dr. F.SJ. Ledgister Dissertation dated May 2012 This study examines the contributions of Joshua and Cato as government and opposition political leaders in the politics and political development of SVG. Checklist of variable of political development is used to ensure objectivity. Various theories of leadership and political development are highlighted. The researcher found that these theories cannot fully explain the conditions existing in small island nations like SVG. SVG is among the few nations which went through stages of transition from colonialism to associate statehood, to independence. This had significant effect on the people and particularly the leaders who inherited a bankrupt country with limited resources and 1 persistent civil disobedience. With regards to political development, the mass of the population saw this as some sort of salvation for fulfillment of their hopes and aspirations. Joshua and Cato led the country for over thirty years. In that period, they have significantly changed the country both in positive and negative directions. These leaders made promises of a better tomorrow if their followers are prepared to make sacrifices. The people obliged with sacrifices, only to become disillusioned because they have not witnessed the promised salvation. The conclusions drawn from the findings suggest that in the process of competing for political power, these leaders have created a series of social ills in SVG. -

La Unión Cívica Radical Intransigente De Tucumán (1957-1962)

Andes ISSN: 0327-1676 ISSN: 1668-8090 [email protected] Instituto de Investigaciones en Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades Argentina EL PARTIDO COMO TERRENO DE DISPUTAS: LA UNIÓN CÍVICA RADICAL INTRANSIGENTE DE TUCUMÁN (1957-1962) Lichtmajer, Leandro Ary EL PARTIDO COMO TERRENO DE DISPUTAS: LA UNIÓN CÍVICA RADICAL INTRANSIGENTE DE TUCUMÁN (1957-1962) Andes, vol. 29, núm. 1, 2018 Instituto de Investigaciones en Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, Argentina Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=12755957009 Esta obra está bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional. PDF generado a partir de XML-JATS4R por Redalyc Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto ARTÍCULOS EL PARTIDO COMO TERRENO DE DISPUTAS: LA UNIÓN CÍVICA RADICAL INTRANSIGENTE DE TUCUMÁN (1957-1962) THE PARTY AS A FIELD OF DISPUTES: THE INTRANSIGENT RADICAL CIVIC UNION OF TUCUMÁN (1957-1962) Leandro Ary Lichtmajer [email protected] Instituto Superior de Estudios Sociales (UNT/CONICET) Facultad de Filosofía y Letras (UNT)., Argentina Resumen: Los interrogantes sobre el derrotero del radicalismo en la etapa de Andes, vol. 29, núm. 1, 2018 inestabilidad política y conflictividad social comprendida entre los golpes de Estado de 1955 y 1962 se vinculan a la necesidad de desentrañar la trayectoria de los partidos Instituto de Investigaciones en Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, Argentina en una etapa clave de la historia argentina contemporánea. En ese contexto, el análisis del surgimiento y trayectoria de la Unión Cívica Radical Intransigente en la provincia Recepción: 18/10/17 de Tucumán (Argentina) procura poner en debate las interpretaciones estructuradas Aprobación: 26/12/17 alrededor de la noción de partido instrumental. -

The Transformation of Party-Union Linkages in Argentine Peronism, 1983–1999*

FROM LABOR POLITICS TO MACHINE POLITICS: The Transformation of Party-Union Linkages in Argentine Peronism, 1983–1999* Steven Levitsky Harvard University Abstract: The Argentine (Peronist) Justicialista Party (PJ)** underwent a far- reaching coalitional transformation during the 1980s and 1990s. Party reformers dismantled Peronism’s traditional mechanisms of labor participation, and clientelist networks replaced unions as the primary linkage to the working and lower classes. By the early 1990s, the PJ had transformed from a labor-dominated party into a machine party in which unions were relatively marginal actors. This process of de-unionization was critical to the PJ’s electoral and policy success during the presidency of Carlos Menem (1989–99). The erosion of union influ- ence facilitated efforts to attract middle-class votes and eliminated a key source of internal opposition to the government’s economic reforms. At the same time, the consolidation of clientelist networks helped the PJ maintain its traditional work- ing- and lower-class base in a context of economic crisis and neoliberal reform. This article argues that Peronism’s radical de-unionization was facilitated by the weakly institutionalized nature of its traditional party-union linkage. Although unions dominated the PJ in the early 1980s, the rules of the game governing their participation were always informal, fluid, and contested, leaving them vulner- able to internal changes in the distribution of power. Such a change occurred during the 1980s, when office-holding politicians used patronage resources to challenge labor’s privileged position in the party. When these politicians gained control of the party in 1987, Peronism’s weakly institutionalized mechanisms of union participation collapsed, paving the way for the consolidation of machine politics—and a steep decline in union influence—during the 1990s. -

Thomas Byrne Edsall Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4d5nd2zb No online items Inventory of the Thomas Byrne Edsall papers Finding aid prepared by Aparna Mukherjee Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2015 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory of the Thomas Byrne 88024 1 Edsall papers Title: Thomas Byrne Edsall papers Date (inclusive): 1965-2014 Collection Number: 88024 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 259 manuscript boxes, 8 oversize boxes.(113.0 Linear Feet) Abstract: Writings, correspondence, notes, memoranda, poll data, statistics, printed matter, and photographs relating to American politics during the presidential administration of Ronald Reagan, especially with regard to campaign contributions and effects on income distribution; and to the gubernatorial administration of Michael Dukakis in Massachusetts, especially with regard to state economic policy, and the campaign of Michael Dukakis as the Democratic candidate for president of the United States in 1988; and to social conditions in the United States. Creator: Edsall, Thomas Byrne Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover -

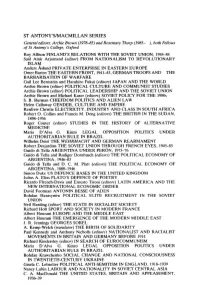

St Antony's/Macmillan Series

ST ANTONY'S/MACMILLAN SERIES General editors: Archie Brown (1978-85) and Rosemary Thorp (1985- ), both Fellows of St Antony's College, Oxford Roy Allison FINLAND'S RELATIONS WITH THE SOVIET UNION, 1944-84 Said Amir Arjomand (editor) FROM NATIONALISM TO REVOLUTIONARY ISLAM Anders Åslund PRIVATE ENTERPRISE IN EASTERN EUROPE Orner Bartov THE EASTERN FRONT, 1941-45, GERMAN TROOPS AND THE BARBARISATION OF WARFARE Gail Lee Bernstein and Haruhiro Fukui (editors) JAPAN AND THE WORLD Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL CULTURE AND COMMUNIST STUDIES Archie Brown (editor) POLITICAL LEADERSHIP AND THE SOVIET UNION Archie Brown and Michael Kaser (editors) SOVIET POLICY FOR THE 1980s S. B. Burman CHIEFDOM POLITICS AND ALIEN LAW Helen Callaway GENDER, CULTURE AND EMPIRE Renfrew Christie ELECTRICITY, INDUSTRY AND CLASS IN SOUTH AFRICA Robert O. Collins and FrancisM. Deng (editors) THE BRITISH IN THE SUDAN, 1898-1956 Roger Couter (editor) STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF ALTERNATIVE MEDICINE Maria D'Alva G. Kinzo LEGAL OPPOSITION POLITICS UNDER AUTHORITARIAN RULE IN BRAZIL Wilhelm Deist THE WEHRMACHT AND GERMAN REARMAMENT Robert Desjardins THE SOVIET UNION THROUGH FRENCH EYES, 1945-85 Guido di Tella ARGENTINA UNDER PERÓN, 1973-76 Guido di Tella and Rudiger Dornbusch (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1946-83 Guido di Tella and D. C. M. Platt (editors) THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ARGENTINA, 1880-1946 Simon Duke US DEFENCE BASES IN THE UNITED KINGDOM Julius A. Elias PLATO'S DEFENCE OF POETRY Ricardo Ffrench-Davis and Ernesto Tironi (editors) LATIN AMERICA AND THE NEW INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC ORDER David Footman ANTONIN BESSE OF ADEN Bohdan Harasymiw POLITICAL ELITE RECRUITMENT IN THE SOVIET UNION Neil Harding (editor) THE STATE IN SOCIALIST SOCIETY Richard Holt SPORT AND SOCIETY IN MODERN FRANCE Albert Hourani EUROPE AND THE MIDDLE EAST Albert Hourani THE EMERGENCE OF THE MODERN MIDDLE EAST J. -

SS 12 Paper V Half 1 Topic 1B

Systems Analysis of David Easton 1 Development of the General Systems Theory (GST) • In early 20 th century the Systems Theory was first applied in Biology by Ludwig Von Bertallanfy. • Then in 1920s Anthropologists Bronislaw Malinowski ( Argonauts of the Western Pacific ) and Radcliffe Brown ( Andaman Islanders ) used this as a theoretical tool for analyzing the behavioural patterns of the primitive tribes. For them it was more important to find out what part a pattern of behaviour in a given social system played in maintaining the system as a whole, rather than how the system had originated. • Logical Positivists like Moritz Schilick, Rudolf Carnap, Otto Von Newrath, Victor Kraft and Herbert Feigl, who used to consider empirically observable and verifiable knowledge as the only valid knowledge had influenced the writings of Herbert Simon and other contemporary political thinkers. • Linguistic Philosophers like TD Weldon ( Vocabulary of Politics ) had rejected all philosophical findings that were beyond sensory verification as meaningless. • Sociologists Robert K Merton and Talcott Parsons for the first time had adopted the Systems Theory in their work. All these developments in the first half of the 20 th century had impacted on the application of the Systems Theory to the study of Political Science. David Easton, Gabriel Almond, G C Powell, Morton Kaplan, Karl Deutsch and other behaviouralists were the pioneers to adopt the Systems Theory for analyzing political phenomena and developing theories in Political Science during late 1950s and 1960s. What is a ‘system’? • Ludwig Von Bertallanfy: A system is “a set of elements standing in inter-action.” • Hall and Fagan: A system is “a set of objects together with relationships between the objects and between their attributes.” • Colin Cherry: The system is “a whole which is compounded of many parts .. -

PERONISM and ANTI-PERONISM: SOCIAL-CULTURAL BASES of POLITICAL IDENTITY in ARGENTINA PIERRE OSTIGUY University of California

PERONISM AND ANTI-PERONISM: SOCIAL-CULTURAL BASES OF POLITICAL IDENTITY IN ARGENTINA PIERRE OSTIGUY University of California at Berkeley Department of Political Science 210 Barrows Hall Berkeley, CA 94720 [email protected] Paper presented at the LASA meeting, in Guadalajara, Mexico, on April 18, 1997 This paper is about political identity and the related issue of types of political appeals in the public arena. It thus deals with a central aspect of political behavior, regarding both voters' preferences and identification, and politicians' electoral strategies. Based on the case of Argentina, it shows the at times unsuspected but unmistakable impact of class-cultural, and more precisely, social-cultural differences on political identity and electoral behavior. Arguing that certain political identities are social-culturally based, this paper introduces a non-ideological, but socio-politically significant, axis of political polarization. As observed in the case of Peronism and anti-Peronism in Argentina, social stratification, particularly along an often- used compound, in surveys, of socio-economic status and education,1 is tightly associated with political behavior, but not so much in Left-Right political terms or even in issue terms (e.g. socio- economic platforms or policies), but rather in social-cultural terms, as seen through the modes and type of political appeals, and figuring centrally in certain already constituted political identities. Forms of political appeals may be mapped in terms of a two-dimensional political space, defined by the intersection of this social-cultural axis with the traditional Left-to-Right spectrum. Also, since already constituted political identities have their origins in the successful "hailing"2 of pluri-facetted people and groups, such a bi-dimensional space also maps political identities. -

De Cliënt in Beeld

Reforming the Rules of the Game Fransje Molenaar Fransje oftheGame theRules Reforming DE CLIËNTINBEELD Party law, or the legal regulation of political parties, has be- come a prominent feature of established and newly transi- tioned party systems alike. In many countries, it has become virtually impossible to organize elections without one party or another turning to the courts with complaints of one of its competitors having transgressed a party law. At the same Reforming the Rules of the Game time, it should be recognized that some party laws are de- signed to have a much larger political impact than others. Th e development and reform of party law in Latin America It remains unknown why some countries adopt party laws that have substantial implications for party politics while other countries’ legislative eff orts are of a very limited scope. Th is dissertation explores why diff erent party laws appear as they do. It builds a theoretical framework of party law reform that departs from the Latin American experience with regulating political parties. Latin America is not necessarily known for its strong party systems or party organizations. Th is raises the important ques- tion of why Latin American politicians turn to party law, and to political parties more generally, to structure political life. Using these questions as a heuristic tool, the dissertation advances the argument that party law reforms provide politicians with access to crucial party organizational resources needed to win elections and to legislate eff ectively. Extending this argument, the dissertation identifi es threats to party organizational resources as an important force shaping adopted party law reforms. -

Argentina: Peronism Returns María Victoria Murillo, S.J

Argentina: Peronism Returns María Victoria Murillo, S.J. Rodrigo Zarazaga Journal of Democracy, Volume 31, Number 2, April 2020, pp. 125-136 (Article) Published by Johns Hopkins University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/753199 [ Access provided at 9 Apr 2020 16:36 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] ARGENTINA: PERONISM RETURNS María Victoria Murillo and Rodrigo Zarazaga, S.J. María Victoria Murillo is professor of political science and interna- tional and public affairs and director of the Institute of Latin American Studies at Columbia University. Rodrigo Zarazaga, S.J., is director of the Center for Research and Social Action (CIAS) and researcher at the National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) in Buenos Aires. The headline news, the main takeaway, from Argentina’s 2019 gen- eral election is encouraging for democracy despite the dire economic situation. Mauricio Macri, a president not associated with the country’s powerful Peronist movement, became the first such chief executive to complete his mandate, whereas two non-Peronists before him had failed to do so.1 Macri would not repeat his term, however. He lost the 27 October 2019 election and then oversaw a peaceful handover of power to his Peronist rival, Alberto Fernández, who won by 48 to 40 percent and whose vice-president is former two-term president Cristina Fernán- dez de Kirchner (no relation). Strikingly, even the economic hard times gripping the country—they are the worst in two decades, and they sank Macri at the polls—could not ruffle the orderliness of the transition. Peaceful changes of administration tend to be taken for granted in democracies, but they are in fact major achievements anywhere. -

Perón: La Construcción Del Mito Político 1943-1955

Poderti, Alicia Estela Perón: La construcción del mito político 1943-1955 Tesis presentada para la obtención del grado de Doctora en Historia Director: Panella, Claudio CITA SUGERIDA: Poderti, A. E. (2011). Perón: La construcción del mito político 1943-1955 [en línea]. Tesis de posgrado. Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación. En Memoria Académica. Disponible en: http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/tesis/te.442/te.442.pdf Documento disponible para su consulta y descarga en Memoria Académica, repositorio institucional de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación (FaHCE) de la Universidad Nacional de La Plata. Gestionado por Bibhuma, biblioteca de la FaHCE. Para más información consulte los sitios: http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar http://www.bibhuma.fahce.unlp.edu.ar Esta obra está bajo licencia 2.5 de Creative Commons Argentina. Atribución-No comercial-Sin obras derivadas 2.5 Universidad Nacional de La Plata Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación Doctorado en Historia TESIS DOCTORAL Tema: PERÓN: LA CONSTRUCCIÓN DEL MITO POLÍTICO (1943-1955) ALICIA ESTELA PODERTI 2010 1 Universidad Nacional de La Plata Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación Doctorado de Historia PERÓN: LA CONSTRUCCIÓN DEL MITO POLÍTICO (1943-1955) TESIS PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR EN HISTORIA Doctorando: Dra. Alicia Poderti (CONICET). Director: DR. CLAUDIO PANELLA (UNLP, Academia Nacional de la Historia) 2 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN 5 Estratos de reinvención 12 El mito político 15 En torno a la teoría y metodología 22 Past & Present: la Historia Socio Cultural 27 Lo dicho, lo escrito, lo oído 32 Junciones: el léxico político y cotidiano 39 Consideraciones bibliográficas 41 I.