ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of Millets

The Story of Millets Millets were the first crops Millets are the future crops Published by: Karnataka State Department of Agriculture, Bengaluru, India with ICAR-Indian Institute of Millets Research, Hyderabad, India This document is for educational and awareness purpose only and not for profit or business publicity purposes 2018 Compiled and edited by: B Venkatesh Bhat, B Dayakar Rao and Vilas A Tonapi ICAR-Indian Institute of Millets Research, Hyderabad Inputs from: Prabhakar, B.Boraiah and Prabhu C. Ganiger (All Indian Coordinated Research Project on Small Millets, University of Agricultural Sciences, Bengaluru, India) Disclaimer The document is a compilation of information from reputed and some popular sources for educational purposes only. The authors do not claim ownership or credit for any content which may be a part of copyrighted material or otherwise. In many cases the sources of content have not been quoted for the sake of lucid reading for educational purposes, but that does not imply authors have claim to the same. Sources of illustrations and photographs have been cited where available and authors do not claim credit for any of the copy righted or third party material. G. Sathish, IFS, Commissioner for Agriculture, Department of Agriculture Government of Karnataka Foreword Millets are the ancient crops of the mankind and are important for rainfed agriculture. They are nutritionally rich and provide number of health benefits to the consumers. With Karnataka being a leading state in millets production and promotion, the government is keen on supporting the farmers and consumers to realize the full potential of these crops. On the occasion of International Organics and Millets Fair, 2018, we are planning before you a story on millets to provide a complete historic global perspective of journey of millets, their health benefits, utilization, current status and future prospects, in association with our knowledge partner ICAR - Indian Institute of Millets Research, with specific inputs from the University of Agricultural Sciences, Bengaluru. -

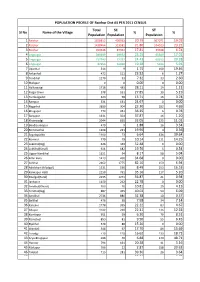

Sl No Name of the Village Total Population SC Population % ST

POPULATION PROFILE OF Raichur Dist AS PER 2011 CENSUS Total SC ST Sl No Name of the Village % % Population Population Population 1 Raichur 1928812 400933 20.79 367071 19.03 2 Raichur 1438464 313581 21.80 334023 23.22 3 Raichur 490348 87352 17.81 33048 6.74 4 Lingsugur 385699 89692 23.25 65589 17.01 5 Lingsugur 297743 72732 24.43 60393 20.28 6 Lingsugur 87956 16960 19.28 5196 5.91 7 Upanhal 514 9 1.75 100 19.46 8 Ankanhal 472 111 23.52 6 1.27 9 Tondihal 1270 93 7.32 33 2.60 10 Mallapur 0 0 0.00 0 0.00 11 Halkawatgi 1718 483 28.11 19 1.11 12 Palgal Dinni 578 161 27.85 30 5.19 13 Tumbalgaddi 423 58 13.71 16 3.78 14 Rampur 531 131 24.67 0 0.00 15 Nagarhal 3880 904 23.30 182 4.69 16 Bhogapur 773 281 36.35 6 0.78 17 Baiyapur 1331 504 37.87 16 1.20 18 Khairwadgi 2044 655 32.05 225 11.01 19 Bandisunkapur 479 9 1.88 16 3.34 20 Bommanhal 1108 221 19.95 4 0.36 21 Sajjalagudda 1100 73 6.64 436 39.64 22 Komnur 779 79 10.14 111 14.25 23 Lukkihal(Big) 646 339 52.48 0 0.00 24 Lukkihal(Small) 921 182 19.76 5 0.54 25 Uppar Nandihal 1151 94 8.17 58 5.04 26 Killar Hatti 1413 490 34.68 0 0.00 27 Ashihal 2162 1775 82.10 150 6.94 28 Advibhavi (Mudgal) 1531 130 8.49 253 16.53 29 Kannapur Hatti 2250 791 35.16 117 5.20 30 Mudgal(Rural) 2235 1271 56.87 21 0.94 31 Jantapur 1150 262 22.78 0 0.00 32 Yerdihal(Khurd) 703 76 10.81 29 4.13 33 Yerdihal(Big) 887 355 40.02 54 6.09 34 Amdihal 2736 886 32.38 10 0.37 35 Bellihal 476 38 7.98 34 7.14 36 Kansavi 1778 395 22.22 83 4.67 37 Adapur 1022 228 22.31 126 12.33 38 Komlapur 951 59 6.20 79 8.31 39 Ramatnal 853 81 9.50 55 -

Journal 16Th Issue

Journal of Indian History and Culture JOURNAL OF INDIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE September 2009 Sixteenth Issue C.P. RAMASWAMI AIYAR INSTITUTE OF INDOLOGICAL RESEARCH (affiliated to the University of Madras) The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road, Chennai 600 018, INDIA September 2009, Sixteenth Issue 1 Journal of Indian History and Culture Editor : Dr.G.J. Sudhakar Board of Editors Dr. K.V.Raman Dr. Nanditha Krishna Referees Dr. A. Chandrsekharan Dr. V. Balambal Dr. S. Vasanthi Dr. Chitra Madhavan Published by Dr. Nanditha Krishna C.P.Ramaswami Aiyar Institute of Indological Research The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road Chennai 600 018 Tel : 2434 1778 / 2435 9366 Fax : 91-44-24351022 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.cprfoundation.org ISSN : 0975 - 7805 Layout Design : R. Sathyanarayanan & P. Dhanalakshmi Sub editing by : Mr. Narayan Onkar Subscription Rs. 150/- (for 2 issues) Rs. 290/- (for 4 issues) 2 September 2009, Sixteenth Issue Journal of Indian History and Culture CONTENTS Prehistoric and Proto historic Strata of the Lower Tungabhadra Region of Andhra Pradesh and Adjoining Areas by Dr. P.C. Venkatasubbiah 07 River Narmada and Valmiki Ramayana by Sukanya Agashe 44 Narasimha in Pallava Art by G. Balaji 52 Trade between Early Historic Tamilnadu and China by Dr. Vikas Kumar Verma 62 Some Unique Anthropomorphic Images Found in the Temples of South India - A Study by R. Ezhilraman 85 Keelakarai Commercial Contacts by Dr. A.H. Mohideen Badshah 101 Neo trends of the Jaina Votaries during the Gangas of Talakad - with a special reference to Military General Chamundararaya by Dr. -

The Archaeobotany of Khao Sam Kaeo and Phu Khao Thong: the Agriculture of Late Prehistoric Southern Thailand (Volume 1)

The Archaeobotany of Khao Sam Kaeo and Phu Khao Thong: The Agriculture of Late Prehistoric Southern Thailand (Volume 1) Cristina Castillo Institute of Archaeology University College London Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of University College London 2013 Declaration I hereby declare that this dissertation consists of original work undertaken by the undersigned. Where other sources of information have been used, they have been acknowledged. Cristina Castillo October 2013 Institute of Archaeology, UCL 2 Abstract The Thai-Malay Peninsula lies at the heart of Southeast Asia. Geographically, the narrowest point is forty kilometres and forms a barrier against straightforward navigation from the Indian Ocean to the South China Sea and vice versa. This would have either led vessels to cabotage the southernmost part of the peninsula or portage across the peninsula to avoid circumnavigating. The peninsula made easy crossing points strategic locations commercially and politically. Early movements of people along exchange routes would have required areas for rest, ports, repair of boats and replenishment of goods. These feeder stations may have grown to become entrepôts and urban centres. This study investigates the archaeobotany of two sites in the Thai-Malay Peninsula, Khao Sam Kaeo and Phu Khao Thong. Khao Sam Kaeo is located on the east whereas Phu Khao Thong lies on the west of the peninsula and both date to the Late Prehistoric period (ca. 400-100 BC). Khao Sam Kaeo has been identified as the earliest urban site from the Late Prehistoric period in Southeast Asia engaged in trans-Asiatic exchange networks. -

Rural Water Supply 07-08 Action Plan

PANCHAYAT RAJ ENGINEERING DIVISION, RAICHUR PROFORMA FOR ACTION PLAN 2007-08 Present water supply Proposed water supply status Scheme Expendi Sl Estimate Gram Panchayat Village/ Habitation ture as on No cost LPCD Taluk TOTAL District 31-3-2007 Remarks HP HP OWS OWS PWSS PWSS MWSS MWSS MWSS MWSS MWSS MWSS for recharging for Supply Levelof Population 2001 Population 2007 Population Amount required Amount required Amount PWSS R/A PWSS MWSSR/A Single phase Single Single phase Single 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011121314151617181920212223 24 25 26 SPILLOVER FOR 2007-08 (STATE SECTOR) 1 RCR RCR Yapaldinni Naradagadde 30 34 3.00 1.77 - - - - - - - - 1 - - - - 1.23 0.00 1.23 Completed 2 RCR RCR Marchetal Pesaldinni 97 107 2.00 0.00 - - 1 - - 114 - - - - - - 1 2.00 0.00 2.00 C-99 In progress 3 RCR RCR Matmari Heerapur 2575 2884 1.25 0.00 1 1 7 - - 40 - A - - - - - 1.25 0.00 1.25 In progress 4 RCR RCR Gillesugur Duganur 1375 1540 2.00 0.00 - 1 4 - - 26 - - - A - - - 2.00 0.00 2.00 C-99 In progress 5 RCR RCR J.Venkatapur Gonal 952 1066 4.50 0.24 - 1 3 - - 30 - - - A - - - 4.26 0.00 4.26 In progress 6 RCR RCR Sagamkunta Mamadadoddi 1125 1260 4.00 0.00 - 1 4 - - 15 - - - R - - - 4.00 0.00 4.00 S.B In progress 7 RCR RCR Kalmala Kalmala 5797 6493 1.00 0.00 2 1 8 - - 23 - A - - - - - 1.00 0.00 1.00 C-99 Completed 8 RCR RCR Mamdapur Nelhal 2242 2511 0.35 0.00 1 1 1 - 1 31 - A - - - - - 0.35 0.00 0.35 S.B- Completed 9 RCR RCR Idapanur Idapanur 4934 5526 4.00 0.00 2 - 8 - - 21 - R - - - - - 4.00 0.00 4.00 S.B In progress 10 RCR RCR Kamalapur Manjarla 1463 1639 1.00 -

Understanding the Stability of Early Iron Age Folks of South India with Special Reference to Krishna-Tungabhadra- Kaveri, Karnataka; Their Past-Present-Future

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Christ University Bengaluru: Open Journal Systems Artha J Soc Sci, 13, 4 (2014), 47-62 ISSN 0975-329X|doi.org/10.12724/ajss.31.4 Understanding the Stability of Early Iron Age folks of South India with Special Reference to Krishna-Tungabhadra- Kaveri, Karnataka; Their Past-Present-Future Arjun R* Abstract There are about 1933 Early Iron Age Megalithic sites spread across South India. The Early Iron Age of South India is implicit either in the form of burial sites, habitation sites, habitation cum burial sites, Iron Age rock art sites, and isolated iron smelting localities near a habitation or burials. This paper is an attempt to take a rough computation of the potentiality of the labour, technology and quantity of artifact output that this cultural phase might have once had, in micro or in macro level. Considering the emergence of technology and its enormous output in Ceramics, Agriculture, Metallurgy and Building up Burials as industries by themselves, that has economic, ethnographic and socio-technique archaeological imprints. This helps in understanding two aspects: one, whether they were nomadic, semi settled or settled at one location; two, the Diffusion versus Indigenous development. A continuity of late Neolithic phase is seen into Early Iron Age and amalgamation of Early Iron Age with the Early Historic Period as evident in the sites like Maski, Brahmagiri, Sanganakallu, Tekkalakota, T-Narasipur. In few cases, Iron Age folks migrated from one location to the other and settled on the river banks in large scale like that in Hallur and Koppa. -

Jim G. Shaffer

Jim G. Shaffer Department of Anthropology, Case Western Reserve University Cleveland, OH 44106-7125 Telephone: 216-368-2267 / Fax: 216-368-5334 / E-mail: [email protected] Webpage: https://anthropology.case.edu/faculty/jim-shaffer/ i. PROFESSIONAL PREPARATION Arizona State University Anthropology B.A., 1965 (Honors) Arizona State University Anthropology M.A., 1967 University of Wisconsin Anthropology Ph.D., 1972 ii. PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 1980 – present Associate Professor, Case Western Reserve University 1972 Assistant Professor, Case Western Reserve University iii. SELECTED PUBLICATIONS Books, Monographs and Dissertation 1978 Shaffer, J.G. Prehistoric Baluchistan: With Excavation Report on Said Qala Tepe. Delhi: B.R. Publishing Corp. 1972 Shaffer, J.G. Prehistoric Baluchistan: A Systematic Approach. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Madison: University of Wisconsin. 1971 Shaffer, J.G. Arizona U: 2:29 (ASU): A Honaki Phase Site on the Lower Verde River, Arizona. M.A. Thesis, Department of Anthropology, Tempe: Arizona State University. Refereed Journal Articles 2013 Shaffer, J.G. and D. A. Lichtenstein. “The Harappan Diaspora.” Vedic Venues 2:248-268. 1998 Shaffer, J.G., Ann S. DuFresne, M.L. Shivashankar and Balasubramanya. "A Preliminary Analysis of Microblades, Blade Cores and Lunates from Watgal: A Southern Neolithic Site." Man and Environment 23(2):17-43. 1995 Shaffer, J.G., D.V. Deavaraj, C.S. Patil, and Balasubramanya. "The Watgal Excavations: An Interim Report." Man and Environment 20(2):57-74. 1986 Shaffer, J.G. "The Archaeology of Baluchistan: A Review." Newsletter of Baluchistan Studies 3(Summer 1986):63-111. 1 1982 Shaffer, J.G. Comment on J.R. Alden's "Trade and Politics in Proto-Elamite Iran." Current Anthropology 23(6):635. -

Ground Water Year Book of Karnataka State 2015-2016

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY No. YB-02/2016-17 GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK OF KARNATAKA STATE 2015-2016 CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD SOUTH WESTERN REGION BANGALORE NOVEMBER 2016 GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK 2015-16 KARNATAKA C O N T E N T S SL.NO. ITEM PAGE NO. FOREWORD ABSTRACT 1 GENERAL FEATURES 1-10 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Physiography 1.3. Drainage 1.4. Geology RAINFALL DISTRIBUTION IN KARNATAKA STATE-2015 2.1 Pre-Monsoon Season -2015 2 2.2 South-west Monsoon Season - 2015 11-19 2.3 North-east Monsoon Season - 2015 2.4 Annual rainfall 3 GROUND WATER LEVELS IN GOA DURING WATER YEAR 20-31 2015-16 3.1 Depth to Ground Water Levels 3.2 Fluctuations in the ground water levels 4 HYDROCHEMISTRY 32-34 5 CONCLUSIONS 35-36 LIST OF FIGURES Fig. 1.1 Administrative set-up of Karnataka State Fig. 1.2 Agro-climatic Zones of Karnataka State Fig. 1.3 Major River Basins of Karnataka State Fig. 1.4 Geological Map of Karnataka Fig. 2.1 Pre-monsoon (2015) rainfall distribution in Karnataka State Fig. 2.2 South -West monsoon (2015) rainfall distribution in Karnataka State Fig. 2.3 North-East monsoon (2015) rainfall distribution in Karnataka State Fig. 2.4 Annual rainfall (2015) distribution in Karnataka State Fig. 3.1 Depth to Water Table Map of Karnataka, May 2015 Fig. 3.2 Depth to Water Table Map of Karnataka, August 2015 Fig. 3.3 Depth to Water Table Map of Karnataka, November 2015 Fig. 3.4 Depth to Water Table Map of Karnataka, January 2016 Fig. -

Man and Environment Man and Environment Abstracts

Man and Environment AbstractsAbstractsAbstracts VVolumeolume XX, No. 1 ((JanuaryJanuaryJanuaryJanuary----JuneJuneJuneJune 199519951995)1995))) Indigenous Perceptions of the Past R.N. Mehta R. N. Mehta, Man and Environment XX(1): 1-6 [1995] ME-1995-1A01 Ancient Cities of Bihar in Archaeology and Literature B.P. Sinha B.P. Sinha, Man and Environment XX(1): 7-20 [1995] ME-1995-1A02 The Early Stone Age of Pakistan: a Methodological Review R.W. Dennell Prehistorians and their scientific colleagues often disagree over the results of archaeological and geological field-work. This is especially so when research teams have worked in the same area and on the same material, but at different times. A good example is the Soan Valley of northern Pakistan, investigated by de Terra and Paterson in the 1930s, and Rendell and Dennell in the 1980s. Both teams attempted to establish a chronological framework for the Early Palaeolithic, but their results are wholly irreconcilable. This paper explores the reasons why, and argues that these differences arose primarily because of the prior expectations of each team. De Terra and Rendell began with fundamentally different preconceptions about the structure of the Pleistocene, the stability of land surfaces, and the validity of long distance correlations. Likewise, Paterson and Dennell each began with profoundly divergent views on the structure of the Early Palaeolithic, and the significance of lithic variability. Crucially, these differences originated well before field-work was even commenced. Field-work must therefore be evaluated within its wider intellectual framework. If researchers begin with radically different assumptions, they are likely to end with incompatible results, and attempts to reconcile those differences are unlikely to be successful. -

2. the Geographical Setting and Pre-Historic Cultures of India

MODULE - 1 Ancient India 2 Notes THE GEOGRAPHICAL SETTING AND PRE-HISTORIC CULTURES OF INDIA The history of any country or region cannot be understood without some knowledge of its geography. The history of the people is greatly conditioned by the geography and environment of the region in which they live. The physical geography and envi- ronmental conditions of a region include climate, soil types, water resources and other topographical features. These determine the settlement pattern, population spread, food products, human behaviour and dietary habits of a region. The Indian subcontinent is gifted with different regions with their distinct geographical features which have greatly affected the course of its history. Geographically speaking the Indian subcontinent in ancient times included the present day India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan and Pakistan. On the basis of geographical diversities the subcontinent can be broadly divided into the follow- ing main regions. These are: (i) The Himalayas (ii) The River Plains of North India (iii) The Peninsular India OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you will be able to: explain the physical divisions of Indian subcontinent; recognize the distinct features of each region; understand why some geographical areas are more important than the others; define the term environment; establish the relationship between geographical features and the historical devel- opments in different regions; define the terms prehistory, prehistoric cultures, and microliths; distinguish between the lower, middle and upper Palaeolithic age on the basis of the tools used; explain the Mesolithic age as a phase of transition on the basis of climate and the 10 HISTORY The Geographical Setting and pre-historic MODULE - 1 Ancient India tools used; explain the Neolithic age and its chief characteristics; differentiate between Palaeolithic and Neolithic periods and learn about the Prehistoric Art. -

Bank Name Branch Name OTHERS(Mobile Van Etc., Name Number )

Raichur District Service Area Plan TYPE OF COVERAGE If covered by Bank Branch If covered by BCA EBRN/EBCA/OTHERS furnish Branch name SSA No. of Population as Sl. Name of the Gram Service Area Sl.N BLOCK SL. SSA NO. Branch Name Names of Revenue Village House- per 2011 No Panchayat Bank o. Existing Branch (EBRN). No. holds Census Existing BCA (EBCA). Branch BCA Mobile Bank Name Covered by BCA - NAME BCA Head quarter Bank Name Branch Name OTHERS(Mobile Van etc., Name Number ) Deodurg B.Ganekal SBH Arakera 1 B.Ganekal 885 4753 EBCA Rajesh 9482769566 Ganekal SBH Ramdurg Deodurg B.Ganekal SBH Arakera 2 Samudra 191 1296 EBCA Rajesh 9482769566 Ganekal SBH Ramdurg 1 Deodurg B.Ganekal 1 SSA152069 SBH Arakera 3 Pandyan 178 1161 EBCA Siddanagouda 9945946624 Pandyan PKGB Galag Deodurg B.Ganekal SBH Arakera 4 Mailapur 35 200 EBCA Siddanagouda 9945946624 Pandyan PKGB Galag Deodurg B.Ganekal SBH Arakera TOTAL 1289 7410 Deodurg Bhumanagunda SBH Arakera 1 Bhumanagunda 413 413 Deodurg Bhumanagunda SBH Arakera Mallapur 366 2394 2 2 SSA152484 2 Deodurg Bhumanagunda SBH Arakera 3 Adakalgudda 206 1278 Deodurg Bhumanagunda SBH Arakera TOTAL 985 4085 Deodurg Alkod SBH Arakera 1 Alkod 413 2126 Deodurg Alkod SBH Arakera 2 Alakumpi 369 2602 3 Deodurg Alkod 3 SSA152068 SBH Arakera 3 Shavantagal 286 1595 Deodurg Alkod SBH Arakera 4 Anwar 185 1201 Deodurg Alkod SBH Arakera TOTAL 1253 7524 Deodurg Arakera PKGB Arakera 1 Arakera 1206 7091 EBRN PKGB Arakera 4 Deodurg Arakera 4 SSA128905 PKGB Arakera 1 HalajadalaDinni 137 824 EBCA Irfan 9591451658 HalajadalaDinni PKGB Arakera Deodurg Arakera PKGB Arakera TOTAL 1343 7915 Deodurg Jagir JadalaDinni PKGB Arakera 1 J.JadalaDinni 354 1830 Deodurg Jagir JadalaDinni PKGB Arakera 2 Jagatkal 298 1519 Deodurg Jagir JadalaDinni PKGB Arakera Rekalamardi 78 388 5 5 SSA121185 3 Deodurg Jagir JadalaDinni PKGB Arakera 4 MarakamaDinni 155 832 Deodurg Jagir JadalaDinni PKGB Arakera 5 Budinnni 228 1337 Deodurg Jagir JadalaDinni PKGB Arakera TOTAL 1113 5906 Deodurg K. -

Neolithic Axe Trade in Raichur Doab, South India

Arch & Anthropol Open Acc Archaeology & Anthropology: Copyright © Arjun R CRIMSON PUBLISHERS C Wings to the Research Open Access ISSN: 2577-1949 Research Article Axe Grinding Grooves in the Absence of Axes: Neolithic Axe Trade in Raichur Doab, South India Arjun R1,2* 1Department of History and Archaeology,Central University of Karnataka, India 2Department of AHIC & Archaeology, Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, India *Corresponding author: Arjun R, Department of History and Archaeology, School of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Central University of Karnataka,Kalaburgi,AHIC & Archaeology,Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, Pune, India Submission: November 01, 2017; Published: June 27, 2018 Abstract In the semi-arid climate and stream channel- granitic inselberg landscapeof Navilagudda in Raichur Doab (Raichur, Karnataka), sixteen prominent axe-grinding grooves over the granitic boulders were recorded. Random reconnaissance at the site indicated no surface scatter of any cultural materials including lithic tool debitage. Within a given limited archaeological data, the primary assertion is, such sites would have performed as non-settlement axe trading centre equipping settlement sites elsewhere during the Neolithic (3000-1200BCE).Statistical and morphological study of the grooves suggests the site was limited to grinding the axe laterals and facets, and there is no such grooves suggesting for axe edge sharpening which could have happened elsewhere in the region or settlement sites. Keywords:South Asia; Southern neolithic; Axe-grinding grooves;Lithic tool strade Introduction The technological innovation of grounding axes/celts developed Dolerite Axe and the Grooves during the Neolithic culture [1-3]. Three stages in the reduction of From past c 150 years, dolerite axes, due to their representative lithic blanks to finished axes were flaking, pecking and grinding/ evidence for Neolithic culture have remained as a favourite polishing/grounding.