Journal 16Th Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hampi, Badami & Around

SCRIPT YOUR ADVENTURE in KARNATAKA WILDLIFE • WATERSPORTS • TREKS • ACTIVITIES This guide is researched and written by Supriya Sehgal 2 PLAN YOUR TRIP CONTENTS 3 Contents PLAN YOUR TRIP .................................................................. 4 Adventures in Karnataka ...........................................................6 Need to Know ........................................................................... 10 10 Top Experiences ...................................................................14 7 Days of Action .......................................................................20 BEST TRIPS ......................................................................... 22 Bengaluru, Ramanagara & Nandi Hills ...................................24 Detour: Bheemeshwari & Galibore Nature Camps ...............44 Chikkamagaluru .......................................................................46 Detour: River Tern Lodge .........................................................53 Kodagu (Coorg) .......................................................................54 Hampi, Badami & Around........................................................68 Coastal Karnataka .................................................................. 78 Detour: Agumbe .......................................................................86 Dandeli & Jog Falls ...................................................................90 Detour: Castle Rock .................................................................94 Bandipur & Nagarhole ...........................................................100 -

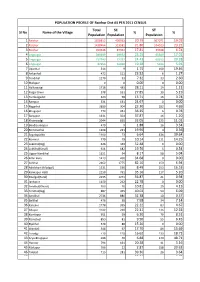

Sl No Name of the Village Total Population SC Population % ST

POPULATION PROFILE OF Raichur Dist AS PER 2011 CENSUS Total SC ST Sl No Name of the Village % % Population Population Population 1 Raichur 1928812 400933 20.79 367071 19.03 2 Raichur 1438464 313581 21.80 334023 23.22 3 Raichur 490348 87352 17.81 33048 6.74 4 Lingsugur 385699 89692 23.25 65589 17.01 5 Lingsugur 297743 72732 24.43 60393 20.28 6 Lingsugur 87956 16960 19.28 5196 5.91 7 Upanhal 514 9 1.75 100 19.46 8 Ankanhal 472 111 23.52 6 1.27 9 Tondihal 1270 93 7.32 33 2.60 10 Mallapur 0 0 0.00 0 0.00 11 Halkawatgi 1718 483 28.11 19 1.11 12 Palgal Dinni 578 161 27.85 30 5.19 13 Tumbalgaddi 423 58 13.71 16 3.78 14 Rampur 531 131 24.67 0 0.00 15 Nagarhal 3880 904 23.30 182 4.69 16 Bhogapur 773 281 36.35 6 0.78 17 Baiyapur 1331 504 37.87 16 1.20 18 Khairwadgi 2044 655 32.05 225 11.01 19 Bandisunkapur 479 9 1.88 16 3.34 20 Bommanhal 1108 221 19.95 4 0.36 21 Sajjalagudda 1100 73 6.64 436 39.64 22 Komnur 779 79 10.14 111 14.25 23 Lukkihal(Big) 646 339 52.48 0 0.00 24 Lukkihal(Small) 921 182 19.76 5 0.54 25 Uppar Nandihal 1151 94 8.17 58 5.04 26 Killar Hatti 1413 490 34.68 0 0.00 27 Ashihal 2162 1775 82.10 150 6.94 28 Advibhavi (Mudgal) 1531 130 8.49 253 16.53 29 Kannapur Hatti 2250 791 35.16 117 5.20 30 Mudgal(Rural) 2235 1271 56.87 21 0.94 31 Jantapur 1150 262 22.78 0 0.00 32 Yerdihal(Khurd) 703 76 10.81 29 4.13 33 Yerdihal(Big) 887 355 40.02 54 6.09 34 Amdihal 2736 886 32.38 10 0.37 35 Bellihal 476 38 7.98 34 7.14 36 Kansavi 1778 395 22.22 83 4.67 37 Adapur 1022 228 22.31 126 12.33 38 Komlapur 951 59 6.20 79 8.31 39 Ramatnal 853 81 9.50 55 -

Mughal Warfare

1111 2 3 4 5111 Mughal Warfare 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 3111 Mughal Warfare offers a much-needed new survey of the military history 4 of Mughal India during the age of imperial splendour from 1500 to 1700. 5 Jos Gommans looks at warfare as an integrated aspect of pre-colonial Indian 6 society. 7 Based on a vast range of primary sources from Europe and India, this 8 thorough study explores the wider geo-political, cultural and institutional 9 context of the Mughal military. Gommans also details practical and tech- 20111 nological aspects of combat, such as gunpowder technologies and the 1 animals used in battle. His comparative analysis throws new light on much- 2 contested theories of gunpowder empires and the spread of the military 3 revolution. 4 As the first original analysis of Mughal warfare for almost a century, this 5 will make essential reading for military specialists, students of military history 6 and general Asian history. 7 8 Jos Gommans teaches Indian history at the Kern Institute of Leiden 9 University in the Netherlands. His previous publications include The Rise 30111 of the Indo-Afghan Empire, 1710–1780 (1995) as well as numerous articles 1 on the medieval and early modern history of South Asia. 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 40111 1 2 3 44111 1111 Warfare and History 2 General Editor 3 Jeremy Black 4 Professor of History, University of Exeter 5 6 Air Power in the Age of Total War The Soviet Military Experience 7 John Buckley Roger R. -

Multiplicity of Phytoplankton Diversity in Tungabhadra River Near Harihar, Karnataka (India)

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2015) 4(2): 1077-1085 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 4 Number 2 (2015) pp. 1077-1085 http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article Multiplicity of phytoplankton diversity in Tungabhadra River near Harihar, Karnataka (India) B. Suresh* Civil Engineering/Environmental Science and Technology Study Centre, Bapuji Institute of Engineering and Technology, Davangere-577 004, Karnataka, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Water is one of the most important precious natural resources required essentially for the survival and health of living organisms. Tungabhadra River is an important tributary of Krishna. It has a drainage area of 71,417 sq km out of which 57,671 sq. km area lies in the state of Karnataka. The study was conducted to measure its various physico-chemical and bacteriological parameters including levels of algal K eywo rd s community. Pollution in water bodies may indicate the environment of algal nutrients in water. They may also function as indicators of pollution. The present Phytoplankton, investigation is an attempt to know the pollution load through algal indicators in multiplicity, Tungabhadra river of Karnataka near Harihar town. The study has been conducted Tungabhadra from May 2008 to April 2009. The tolerant genera and species of four groups of river. algae namely, Chlorophyceae, Bacilleriophyceae, Cyanaophyceae and Euglenophyceae indicate that total algal population is 17,715 in station No. S3, which has the influence of industrial pollution by Harihar Polyfibre and Grasim industry situated on the bank of the river which are discharging its treated effluent to this river. -

1 Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: 1 Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title South Indian kingdoms : pallavas and chalukyas Module Id I C/ OIH/ 15 Political developments in South India after Pre-requisites Satavavahana and Sangam age To study the Political and Cultural history of South Objectives India under Pallava and Chalukyan periods Keywords Pallava / Kanchi / Chalukya / Badami E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Introduction The period from C.300 CE to 750 CE marks the second historical phase in the regions south of the Vindhyas. In the first phase we notice the ascendency of the Satavahanas over the Deccan and that of the Sangam Age Kingdoms in Southern Tamilnadu. In these areas and also in Vidarbha from 3rd Century to 6th Century CE there arose about two dozen states which are known to us from their land charters. In Northern Maharashtra and Vidarbha (Berar) the Satavahanas were succeeded by the Vakatakas. Their political history is of more importance to the North India than the South India. But culturally the Vakataka kingdom became a channel for transmitting Brahmanical ideas and social institutions to the South. The Vakataka power was followed by that of the Chalukyas of Badami who played an important role in the history of the Deccan and South India for about two centuries until 753 CE when they were overthrown by their feudatories, the Rashtrakutas. The eastern part of the Satavahana Kingdom, the Deltas of the Krishna and the Godavari had been conquered by the Ikshvaku dynasty in the 3rd Century CE. -

Monasteries in Medieval Tamilnadu Michelle L. Folk a Thesis in The

Ascetics, Devotees, Disciples, and Lords of the Maṭam: Monasteries in Medieval Tamilnadu Michelle L. Folk A Thesis in the Department of Religion Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Religion) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2013 © Michelle L. Folk, 2013 ii CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Michelle L. Folk Entitled: Ascetics, Devotees, Disciples, and Lords of the Maṭam: Monasteries in Medieval Tamilnadu and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Religion) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: ___________________________________________ Chair Prof. Arpi Hamalian ___________________________________________ External Examiner Dr. Richard Mann ___________________________________________ External to Program Dr. Alan E. Nash ___________________________________________ Examiner Dr. Mathieu Boisvert ___________________________________________ Examiner Dr. Shaman Hatley ___________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor Dr. Leslie C. Orr Approved by ___________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director July 25, 2013 ________________________________________________ Dean of Faculty iii Abstract Ascetics, Devotees, Disciples, and Lords of the Maṭam: Monasteries in Medieval Tamilnadu Michelle -

Assessment of Water Quality Changes in Krishna River of Andhrap Radesh Through Geoinformatics

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering (IJRTE) ISSN: 2277-3878, Volume-7, Issue-6C2, April 2019 Assessment of Water Quality Changes in Krishna River of Andhrap radesh Through Geoinformatics Lakshman Kumar.C.H, D. Satish Chandra, S.S.Asadi Abstract--- Pancha Boothas are Life and Death for the are permissible in river water but exceed their level its Environment. In that any one is Disrupted that can be Escort to causes several diseases for users and Toxic elements, excess the danger of environment. Water is the one of the Pancha nutrients create vadose zones in river courses [5]. Most of Boothas. Quality of the water is very crucial in the present and the assured irrigation in India is surface water of rivers. It is future users. Natural issues and manmade activities are depending on the water quality. The ratio of transportation of essential to monitor and assess the water quality in the fresh water in liquid form to covert useless form is 70%. The Krishna river course. ratio of sedimentation is also one of the parameter of the water quality, if changes are happen in sedimentation the quality of the Notations: water also changes. The causes of water pollution source are GDSQ: Gauge Discharge Sediment and Water Quality many, of which sewage discharge, industrial effluents, agricultural effluents and several man made activities are play a GDQ : Gauge Discharge Water Quality key role on water quality. The total percentage of water in the pH : Potential of Hydrogen world is 97% in Oceans and reaming 3% of water in form of EC : Electric Conductivity glaciers, in which the consumption of water quantity is in form of CO3 : Carbonate surface and subsurface water bodies. -

CUDDALORE (Tamil Nadu) Issued On: 01-10-2021

India Meteorological Department Ministry of Earth Sciences Govt. of India Date: 01-10-2021 Block Level Forecast Weather Forecast of ANNAGRAMAM Block in CUDDALORE (Tamil Nadu) Issued On: 01-10-2021 Wind Wind Cloud Date Rainfall Tmax Tmin RH Morning RH Evening Speed Direction Cover (Y-M-D) (mm) (°C) (°C) (%) (%) (kmph) (°) (Octa) 2021-10-02 14.5 31.3 23.1 85 53 9.0 101 7 2021-10-03 5.9 32.3 23.3 84 51 8.0 101 6 2021-10-04 0.0 32.0 23.3 83 51 8.0 90 5 2021-10-05 9.5 31.5 23.3 84 56 7.0 68 5 2021-10-06 11.6 31.4 23.3 84 55 13.0 124 6 Weather Forecast of CUDDALORE Block in CUDDALORE (Tamil Nadu) Issued On: 01-10-2021 Wind Wind Cloud Date Rainfall Tmax Tmin RH Morning RH Evening Speed Direction Cover (Y-M-D) (mm) (°C) (°C) (%) (%) (kmph) (°) (Octa) 2021-10-02 12.3 32.3 23.3 82 62 10.0 101 7 2021-10-03 5.9 32.9 23.7 78 62 10.0 109 5 2021-10-04 0.0 32.9 23.7 80 59 9.0 60 5 2021-10-05 7.8 32.4 23.8 77 62 8.0 70 4 2021-10-06 8.5 32.3 23.7 79 63 17.0 124 5 Weather Forecast of KAMMAPURAM Block in CUDDALORE (Tamil Nadu) Issued On: 01-10-2021 Wind Wind Cloud Date Rainfall Tmax Tmin RH Morning RH Evening Speed Direction Cover (Y-M-D) (mm) (°C) (°C) (%) (%) (kmph) (°) (Octa) 2021-10-02 4.7 31.3 23.8 81 55 8.0 101 8 2021-10-03 4.3 32.4 23.6 85 50 7.0 90 6 2021-10-04 0.1 32.6 24.0 83 52 7.0 293 5 2021-10-05 4.5 33.0 23.7 82 49 8.0 90 5 2021-10-06 17.0 32.1 23.8 85 50 11.0 124 6 India Meteorological Department Ministry of Earth Sciences Govt. -

I Year Dkh11 : History of Tamilnadu Upto 1967 A.D

M.A. HISTORY - I YEAR DKH11 : HISTORY OF TAMILNADU UPTO 1967 A.D. SYLLABUS Unit - I Introduction : Influence of Geography and Topography on the History of Tamil Nadu - Sources of Tamil Nadu History - Races and Tribes - Pre-history of Tamil Nadu. SangamPeriod : Chronology of the Sangam - Early Pandyas – Administration, Economy, Trade and Commerce - Society - Religion - Art and Architecture. Unit - II The Kalabhras - The Early Pallavas, Origin - First Pandyan Empire - Later PallavasMahendravarma and Narasimhavarman, Pallava’s Administration, Society, Religion, Literature, Art and Architecture. The CholaEmpire : The Imperial Cholas and the Chalukya Cholas, Administration, Society, Education and Literature. Second PandyanEmpire : Political History, Administration, Social Life, Art and Architecture. Unit - III Madurai Sultanate - Tamil Nadu under Vijayanagar Ruler : Administration and Society, Economy, Trade and Commerce, Religion, Art and Architecture - Battle of Talikota 1565 - Kumarakampana’s expedition to Tamil Nadu. Nayakas of Madurai - ViswanathaNayak, MuthuVirappaNayak, TirumalaNayak, Mangammal, Meenakshi. Nayakas of Tanjore :SevappaNayak, RaghunathaNayak, VijayaRaghavaNayak. Nayak of Jingi : VaiyappaTubakiKrishnappa, Krishnappa I, Krishnappa II, Nayak Administration, Life of the people - Culture, Art and Architecture. The Setupatis of Ramanathapuram - Marathas of Tanjore - Ekoji, Serfoji, Tukoji, Serfoji II, Sivaji III - The Europeans in Tamil Nadu. Unit - IV Tamil Nadu under the Nawabs of Arcot - The Carnatic Wars, Administration under the Nawabs - The Mysoreans in Tamil Nadu - The Poligari System - The South Indian Rebellion - The Vellore Mutini- The Land Revenue Administration and Famine Policy - Education under the Company - Growth of Language and Literature in 19th and 20th centuries - Organization of Judiciary - Self Respect Movement. Unit - V Tamil Nadu in Freedom Struggle - Tamil Nadu under Rajaji and Kamaraj - Growth of Education - Anti Hindi & Agitation. -

Marma in Yoga and Other Ancient Indian Traditions 1

Exploring the Science of Marma - An Ancient Healing Technique - Part 3: Marma in Yoga and Other Ancient Indian Traditions Alka Mishra*, Vandana Shrivastava Department of Ayurveda and Holistic Health, Dev Sanskriti Vishwavidyalaya, Gayatrikunj-Shantikunj, Haridwar, Uttarakhand, India *Corresponding Author: Alka Mishra - Email: [email protected] License information for readers: This paper is published online under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) License, whose full terms may be seen at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Uploaded online: 27 June 2020 Abstract Marma Science is an extremely important branch of Ayurveda. Marma points are important vital places in the body, that are the ‘seats of life’ (Prana - the vital life force). As any injury to these parts may lead to severe pain, disability, loss of function, loss of sensation, or death, therefore, they hold an important place in the science of surgery, wherein they are considered ‘Shalya Vishayardha’ (half of the entire science of surgery). The ancient scriptures have strictly directed against causing any injury to these vital spots. However, recent researches have attempted the stimulation of Marma points for theraputic benefits, with encouraging outcomes. In view of these mutually conflicting, importance applications of Marma Science, the present study was undertaken for its in-depth study. Part-1 of this study presented the information about different aspects of Marma Science in various ancient / classical Indian scriptures. Part-2 gave a detailed description of the number of marmas, their location, structures involved, classification, effect of trauma, etc., as per classical texts, as well as correlation with modern science. -

Cuddalore District

DISTRICT DIAGNOSTIC REPORT (DDR) Tamil Nadu Rural Transformation Project Cuddalore District 1 1 DDR - CUDDALORE 2 DDR - CUDDALORE Table of Contents S.No Contents Page No 1.0 Introduction 10 1.1 About Tamil Nadu Rural Transformation Project - TNRTP 1.2 About District Diagnostic Study – DDS 2.0 CUDDALORE DISTRICT 12 2.1 District Profile 3.0 Socio Demographic profile 14 3.1 Population 3.2 Sex Ratio 3.3 Literacy rate 3.4 Occupation 3.5 Community based institutions 3.6 Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) 4.0 District economic profile 21 4.1 Labour and Employment 4.2 Connectivity 5.0 GEOGRAPHIC PROFILE 25 5.1 Topography 5.2 Land Use Pattern of the District 5.3 Land types 5.4 Climate and Rainfall 5.5 Disaster Vulnerability 5.6 Soil 5.7 Water Resources 31 DDR - CUDDALORE S.No Contents Page No 6.0 STATUS OF GROUND WATER 32 7.0 FARM SECTOR 33 7.1 Land holding pattern 7.2 Irrigation 7.3 Cropping pattern and Major crops 7.4 Block wise (TNRTP) cropping area distribution 7.5 Prioritization of crops 7.6 Crop wise discussion 8.0 MARKETING AND STORAGE INFRASTRUCTURE 44 9.0 AGRIBUSINESS OPPORTUNITIES 46 10.0 NATIONAL AND STATE SCHEMES ON AGRICULTURE 48 11.0 RESOURCE INSTITUTIONS 49 12.0 ALLIED SECTORS 50 12.1 Animal Husbandry and Dairy development 12.2 Poultry 12.3 Fisheries 12.4 Sericulture 4 DDR - CUDDALORE S.No Contents Page No 13.0 NON-FARM SECTORS 55 13.1 Industrial scenario in the district 13.2 MSME clusters 13.3 Manufacturing 13.4 Service sectors 13.5 Tourism 14.0 SKILL GAPS 65 15.0 BANKING AND CREDIT 67 16.0 COMMODITY PRIORITISATION 69 SWOT ANALYSIS 72 CONCLUSION 73 ANNEXURE 76 51 DDR - CUDDALORE List of Tables Table Number and details Page No Table .1. -

Rural Water Supply 07-08 Action Plan

PANCHAYAT RAJ ENGINEERING DIVISION, RAICHUR PROFORMA FOR ACTION PLAN 2007-08 Present water supply Proposed water supply status Scheme Expendi Sl Estimate Gram Panchayat Village/ Habitation ture as on No cost LPCD Taluk TOTAL District 31-3-2007 Remarks HP HP OWS OWS PWSS PWSS MWSS MWSS MWSS MWSS MWSS MWSS for recharging for Supply Levelof Population 2001 Population 2007 Population Amount required Amount required Amount PWSS R/A PWSS MWSSR/A Single phase Single Single phase Single 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011121314151617181920212223 24 25 26 SPILLOVER FOR 2007-08 (STATE SECTOR) 1 RCR RCR Yapaldinni Naradagadde 30 34 3.00 1.77 - - - - - - - - 1 - - - - 1.23 0.00 1.23 Completed 2 RCR RCR Marchetal Pesaldinni 97 107 2.00 0.00 - - 1 - - 114 - - - - - - 1 2.00 0.00 2.00 C-99 In progress 3 RCR RCR Matmari Heerapur 2575 2884 1.25 0.00 1 1 7 - - 40 - A - - - - - 1.25 0.00 1.25 In progress 4 RCR RCR Gillesugur Duganur 1375 1540 2.00 0.00 - 1 4 - - 26 - - - A - - - 2.00 0.00 2.00 C-99 In progress 5 RCR RCR J.Venkatapur Gonal 952 1066 4.50 0.24 - 1 3 - - 30 - - - A - - - 4.26 0.00 4.26 In progress 6 RCR RCR Sagamkunta Mamadadoddi 1125 1260 4.00 0.00 - 1 4 - - 15 - - - R - - - 4.00 0.00 4.00 S.B In progress 7 RCR RCR Kalmala Kalmala 5797 6493 1.00 0.00 2 1 8 - - 23 - A - - - - - 1.00 0.00 1.00 C-99 Completed 8 RCR RCR Mamdapur Nelhal 2242 2511 0.35 0.00 1 1 1 - 1 31 - A - - - - - 0.35 0.00 0.35 S.B- Completed 9 RCR RCR Idapanur Idapanur 4934 5526 4.00 0.00 2 - 8 - - 21 - R - - - - - 4.00 0.00 4.00 S.B In progress 10 RCR RCR Kamalapur Manjarla 1463 1639 1.00