Man and Environment Man and Environment Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

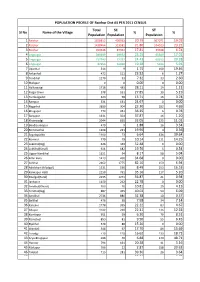

Sl No Name of the Village Total Population SC Population % ST

POPULATION PROFILE OF Raichur Dist AS PER 2011 CENSUS Total SC ST Sl No Name of the Village % % Population Population Population 1 Raichur 1928812 400933 20.79 367071 19.03 2 Raichur 1438464 313581 21.80 334023 23.22 3 Raichur 490348 87352 17.81 33048 6.74 4 Lingsugur 385699 89692 23.25 65589 17.01 5 Lingsugur 297743 72732 24.43 60393 20.28 6 Lingsugur 87956 16960 19.28 5196 5.91 7 Upanhal 514 9 1.75 100 19.46 8 Ankanhal 472 111 23.52 6 1.27 9 Tondihal 1270 93 7.32 33 2.60 10 Mallapur 0 0 0.00 0 0.00 11 Halkawatgi 1718 483 28.11 19 1.11 12 Palgal Dinni 578 161 27.85 30 5.19 13 Tumbalgaddi 423 58 13.71 16 3.78 14 Rampur 531 131 24.67 0 0.00 15 Nagarhal 3880 904 23.30 182 4.69 16 Bhogapur 773 281 36.35 6 0.78 17 Baiyapur 1331 504 37.87 16 1.20 18 Khairwadgi 2044 655 32.05 225 11.01 19 Bandisunkapur 479 9 1.88 16 3.34 20 Bommanhal 1108 221 19.95 4 0.36 21 Sajjalagudda 1100 73 6.64 436 39.64 22 Komnur 779 79 10.14 111 14.25 23 Lukkihal(Big) 646 339 52.48 0 0.00 24 Lukkihal(Small) 921 182 19.76 5 0.54 25 Uppar Nandihal 1151 94 8.17 58 5.04 26 Killar Hatti 1413 490 34.68 0 0.00 27 Ashihal 2162 1775 82.10 150 6.94 28 Advibhavi (Mudgal) 1531 130 8.49 253 16.53 29 Kannapur Hatti 2250 791 35.16 117 5.20 30 Mudgal(Rural) 2235 1271 56.87 21 0.94 31 Jantapur 1150 262 22.78 0 0.00 32 Yerdihal(Khurd) 703 76 10.81 29 4.13 33 Yerdihal(Big) 887 355 40.02 54 6.09 34 Amdihal 2736 886 32.38 10 0.37 35 Bellihal 476 38 7.98 34 7.14 36 Kansavi 1778 395 22.22 83 4.67 37 Adapur 1022 228 22.31 126 12.33 38 Komlapur 951 59 6.20 79 8.31 39 Ramatnal 853 81 9.50 55 -

Journal 16Th Issue

Journal of Indian History and Culture JOURNAL OF INDIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE September 2009 Sixteenth Issue C.P. RAMASWAMI AIYAR INSTITUTE OF INDOLOGICAL RESEARCH (affiliated to the University of Madras) The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road, Chennai 600 018, INDIA September 2009, Sixteenth Issue 1 Journal of Indian History and Culture Editor : Dr.G.J. Sudhakar Board of Editors Dr. K.V.Raman Dr. Nanditha Krishna Referees Dr. A. Chandrsekharan Dr. V. Balambal Dr. S. Vasanthi Dr. Chitra Madhavan Published by Dr. Nanditha Krishna C.P.Ramaswami Aiyar Institute of Indological Research The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road Chennai 600 018 Tel : 2434 1778 / 2435 9366 Fax : 91-44-24351022 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.cprfoundation.org ISSN : 0975 - 7805 Layout Design : R. Sathyanarayanan & P. Dhanalakshmi Sub editing by : Mr. Narayan Onkar Subscription Rs. 150/- (for 2 issues) Rs. 290/- (for 4 issues) 2 September 2009, Sixteenth Issue Journal of Indian History and Culture CONTENTS Prehistoric and Proto historic Strata of the Lower Tungabhadra Region of Andhra Pradesh and Adjoining Areas by Dr. P.C. Venkatasubbiah 07 River Narmada and Valmiki Ramayana by Sukanya Agashe 44 Narasimha in Pallava Art by G. Balaji 52 Trade between Early Historic Tamilnadu and China by Dr. Vikas Kumar Verma 62 Some Unique Anthropomorphic Images Found in the Temples of South India - A Study by R. Ezhilraman 85 Keelakarai Commercial Contacts by Dr. A.H. Mohideen Badshah 101 Neo trends of the Jaina Votaries during the Gangas of Talakad - with a special reference to Military General Chamundararaya by Dr. -

Rural Water Supply 07-08 Action Plan

PANCHAYAT RAJ ENGINEERING DIVISION, RAICHUR PROFORMA FOR ACTION PLAN 2007-08 Present water supply Proposed water supply status Scheme Expendi Sl Estimate Gram Panchayat Village/ Habitation ture as on No cost LPCD Taluk TOTAL District 31-3-2007 Remarks HP HP OWS OWS PWSS PWSS MWSS MWSS MWSS MWSS MWSS MWSS for recharging for Supply Levelof Population 2001 Population 2007 Population Amount required Amount required Amount PWSS R/A PWSS MWSSR/A Single phase Single Single phase Single 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011121314151617181920212223 24 25 26 SPILLOVER FOR 2007-08 (STATE SECTOR) 1 RCR RCR Yapaldinni Naradagadde 30 34 3.00 1.77 - - - - - - - - 1 - - - - 1.23 0.00 1.23 Completed 2 RCR RCR Marchetal Pesaldinni 97 107 2.00 0.00 - - 1 - - 114 - - - - - - 1 2.00 0.00 2.00 C-99 In progress 3 RCR RCR Matmari Heerapur 2575 2884 1.25 0.00 1 1 7 - - 40 - A - - - - - 1.25 0.00 1.25 In progress 4 RCR RCR Gillesugur Duganur 1375 1540 2.00 0.00 - 1 4 - - 26 - - - A - - - 2.00 0.00 2.00 C-99 In progress 5 RCR RCR J.Venkatapur Gonal 952 1066 4.50 0.24 - 1 3 - - 30 - - - A - - - 4.26 0.00 4.26 In progress 6 RCR RCR Sagamkunta Mamadadoddi 1125 1260 4.00 0.00 - 1 4 - - 15 - - - R - - - 4.00 0.00 4.00 S.B In progress 7 RCR RCR Kalmala Kalmala 5797 6493 1.00 0.00 2 1 8 - - 23 - A - - - - - 1.00 0.00 1.00 C-99 Completed 8 RCR RCR Mamdapur Nelhal 2242 2511 0.35 0.00 1 1 1 - 1 31 - A - - - - - 0.35 0.00 0.35 S.B- Completed 9 RCR RCR Idapanur Idapanur 4934 5526 4.00 0.00 2 - 8 - - 21 - R - - - - - 4.00 0.00 4.00 S.B In progress 10 RCR RCR Kamalapur Manjarla 1463 1639 1.00 -

Jim G. Shaffer

Jim G. Shaffer Department of Anthropology, Case Western Reserve University Cleveland, OH 44106-7125 Telephone: 216-368-2267 / Fax: 216-368-5334 / E-mail: [email protected] Webpage: https://anthropology.case.edu/faculty/jim-shaffer/ i. PROFESSIONAL PREPARATION Arizona State University Anthropology B.A., 1965 (Honors) Arizona State University Anthropology M.A., 1967 University of Wisconsin Anthropology Ph.D., 1972 ii. PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 1980 – present Associate Professor, Case Western Reserve University 1972 Assistant Professor, Case Western Reserve University iii. SELECTED PUBLICATIONS Books, Monographs and Dissertation 1978 Shaffer, J.G. Prehistoric Baluchistan: With Excavation Report on Said Qala Tepe. Delhi: B.R. Publishing Corp. 1972 Shaffer, J.G. Prehistoric Baluchistan: A Systematic Approach. Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Madison: University of Wisconsin. 1971 Shaffer, J.G. Arizona U: 2:29 (ASU): A Honaki Phase Site on the Lower Verde River, Arizona. M.A. Thesis, Department of Anthropology, Tempe: Arizona State University. Refereed Journal Articles 2013 Shaffer, J.G. and D. A. Lichtenstein. “The Harappan Diaspora.” Vedic Venues 2:248-268. 1998 Shaffer, J.G., Ann S. DuFresne, M.L. Shivashankar and Balasubramanya. "A Preliminary Analysis of Microblades, Blade Cores and Lunates from Watgal: A Southern Neolithic Site." Man and Environment 23(2):17-43. 1995 Shaffer, J.G., D.V. Deavaraj, C.S. Patil, and Balasubramanya. "The Watgal Excavations: An Interim Report." Man and Environment 20(2):57-74. 1986 Shaffer, J.G. "The Archaeology of Baluchistan: A Review." Newsletter of Baluchistan Studies 3(Summer 1986):63-111. 1 1982 Shaffer, J.G. Comment on J.R. Alden's "Trade and Politics in Proto-Elamite Iran." Current Anthropology 23(6):635. -

Ground Water Year Book of Karnataka State 2015-2016

FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY No. YB-02/2016-17 GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK OF KARNATAKA STATE 2015-2016 CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD SOUTH WESTERN REGION BANGALORE NOVEMBER 2016 GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK 2015-16 KARNATAKA C O N T E N T S SL.NO. ITEM PAGE NO. FOREWORD ABSTRACT 1 GENERAL FEATURES 1-10 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Physiography 1.3. Drainage 1.4. Geology RAINFALL DISTRIBUTION IN KARNATAKA STATE-2015 2.1 Pre-Monsoon Season -2015 2 2.2 South-west Monsoon Season - 2015 11-19 2.3 North-east Monsoon Season - 2015 2.4 Annual rainfall 3 GROUND WATER LEVELS IN GOA DURING WATER YEAR 20-31 2015-16 3.1 Depth to Ground Water Levels 3.2 Fluctuations in the ground water levels 4 HYDROCHEMISTRY 32-34 5 CONCLUSIONS 35-36 LIST OF FIGURES Fig. 1.1 Administrative set-up of Karnataka State Fig. 1.2 Agro-climatic Zones of Karnataka State Fig. 1.3 Major River Basins of Karnataka State Fig. 1.4 Geological Map of Karnataka Fig. 2.1 Pre-monsoon (2015) rainfall distribution in Karnataka State Fig. 2.2 South -West monsoon (2015) rainfall distribution in Karnataka State Fig. 2.3 North-East monsoon (2015) rainfall distribution in Karnataka State Fig. 2.4 Annual rainfall (2015) distribution in Karnataka State Fig. 3.1 Depth to Water Table Map of Karnataka, May 2015 Fig. 3.2 Depth to Water Table Map of Karnataka, August 2015 Fig. 3.3 Depth to Water Table Map of Karnataka, November 2015 Fig. 3.4 Depth to Water Table Map of Karnataka, January 2016 Fig. -

ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER History

PARIPEX - INDIAN JOURNAL OF RESEARCH VOLUME-6 | ISSUE-7 | JULY-2017 | ISSN - 2250-1991 | IF : 5.761 | IC Value : 79.96 ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER History Understanding the Evolution of Southern KEY WORDS: Society- Neolithic Society Archaeology- Neolithic- South India Avantika Sharma University of Delhi Contemporaneous to Indus Civilization, the southern Neolithic Culture dominated south India from 3000 BCE to 1400 BCE. This vast timeline was further divided into three phases by Allchins. In their opinion, the three phases saw a transition from a predominantly pastoral society to a settled agricultural one. In this paper, we revisit the three phases and attempt to understand the development of society in each phase. For this purpose, we rely on anthropological concepts of band, tribes, chiefdom and state. ABSTRACT 1.1 Introduction: 1.2 Phase I The period between 3000 BCE to 1400 BCE, the southern From stratigraphy and radiocarbon dates available, we can infer landscape was dominated by Neolithic culture. The significance that the earliest settlements involved founding of ashmound sites of the Neolithic phase was first diagnosed by Gordon Childe,1 who like Utnur, Piklihal, Kupgal, Kodekal, Kudatini, and Watgal. In the saw it as nothing less than a revolution. The most important recent years, Fuller and his team have sub-divided the phase into a changes of this phase were animal and plant domestication. It has non-ashmound phase (IA) and ashmound phase (IB).14 Sub-phase been argued that they created the economic base for surplus (IA) dated between 3000- 2500 BCE was discovered at Utnur, production from which further complex societies could emerge. -

Bank Name Branch Name OTHERS(Mobile Van Etc., Name Number )

Raichur District Service Area Plan TYPE OF COVERAGE If covered by Bank Branch If covered by BCA EBRN/EBCA/OTHERS furnish Branch name SSA No. of Population as Sl. Name of the Gram Service Area Sl.N BLOCK SL. SSA NO. Branch Name Names of Revenue Village House- per 2011 No Panchayat Bank o. Existing Branch (EBRN). No. holds Census Existing BCA (EBCA). Branch BCA Mobile Bank Name Covered by BCA - NAME BCA Head quarter Bank Name Branch Name OTHERS(Mobile Van etc., Name Number ) Deodurg B.Ganekal SBH Arakera 1 B.Ganekal 885 4753 EBCA Rajesh 9482769566 Ganekal SBH Ramdurg Deodurg B.Ganekal SBH Arakera 2 Samudra 191 1296 EBCA Rajesh 9482769566 Ganekal SBH Ramdurg 1 Deodurg B.Ganekal 1 SSA152069 SBH Arakera 3 Pandyan 178 1161 EBCA Siddanagouda 9945946624 Pandyan PKGB Galag Deodurg B.Ganekal SBH Arakera 4 Mailapur 35 200 EBCA Siddanagouda 9945946624 Pandyan PKGB Galag Deodurg B.Ganekal SBH Arakera TOTAL 1289 7410 Deodurg Bhumanagunda SBH Arakera 1 Bhumanagunda 413 413 Deodurg Bhumanagunda SBH Arakera Mallapur 366 2394 2 2 SSA152484 2 Deodurg Bhumanagunda SBH Arakera 3 Adakalgudda 206 1278 Deodurg Bhumanagunda SBH Arakera TOTAL 985 4085 Deodurg Alkod SBH Arakera 1 Alkod 413 2126 Deodurg Alkod SBH Arakera 2 Alakumpi 369 2602 3 Deodurg Alkod 3 SSA152068 SBH Arakera 3 Shavantagal 286 1595 Deodurg Alkod SBH Arakera 4 Anwar 185 1201 Deodurg Alkod SBH Arakera TOTAL 1253 7524 Deodurg Arakera PKGB Arakera 1 Arakera 1206 7091 EBRN PKGB Arakera 4 Deodurg Arakera 4 SSA128905 PKGB Arakera 1 HalajadalaDinni 137 824 EBCA Irfan 9591451658 HalajadalaDinni PKGB Arakera Deodurg Arakera PKGB Arakera TOTAL 1343 7915 Deodurg Jagir JadalaDinni PKGB Arakera 1 J.JadalaDinni 354 1830 Deodurg Jagir JadalaDinni PKGB Arakera 2 Jagatkal 298 1519 Deodurg Jagir JadalaDinni PKGB Arakera Rekalamardi 78 388 5 5 SSA121185 3 Deodurg Jagir JadalaDinni PKGB Arakera 4 MarakamaDinni 155 832 Deodurg Jagir JadalaDinni PKGB Arakera 5 Budinnni 228 1337 Deodurg Jagir JadalaDinni PKGB Arakera TOTAL 1113 5906 Deodurg K. -

Neolithic Axe Trade in Raichur Doab, South India

Arch & Anthropol Open Acc Archaeology & Anthropology: Copyright © Arjun R CRIMSON PUBLISHERS C Wings to the Research Open Access ISSN: 2577-1949 Research Article Axe Grinding Grooves in the Absence of Axes: Neolithic Axe Trade in Raichur Doab, South India Arjun R1,2* 1Department of History and Archaeology,Central University of Karnataka, India 2Department of AHIC & Archaeology, Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, India *Corresponding author: Arjun R, Department of History and Archaeology, School of Social and Behavioural Sciences, Central University of Karnataka,Kalaburgi,AHIC & Archaeology,Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, Pune, India Submission: November 01, 2017; Published: June 27, 2018 Abstract In the semi-arid climate and stream channel- granitic inselberg landscapeof Navilagudda in Raichur Doab (Raichur, Karnataka), sixteen prominent axe-grinding grooves over the granitic boulders were recorded. Random reconnaissance at the site indicated no surface scatter of any cultural materials including lithic tool debitage. Within a given limited archaeological data, the primary assertion is, such sites would have performed as non-settlement axe trading centre equipping settlement sites elsewhere during the Neolithic (3000-1200BCE).Statistical and morphological study of the grooves suggests the site was limited to grinding the axe laterals and facets, and there is no such grooves suggesting for axe edge sharpening which could have happened elsewhere in the region or settlement sites. Keywords:South Asia; Southern neolithic; Axe-grinding grooves;Lithic tool strade Introduction The technological innovation of grounding axes/celts developed Dolerite Axe and the Grooves during the Neolithic culture [1-3]. Three stages in the reduction of From past c 150 years, dolerite axes, due to their representative lithic blanks to finished axes were flaking, pecking and grinding/ evidence for Neolithic culture have remained as a favourite polishing/grounding. -

Bedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA

pincode officename districtname statename 560001 Dr. Ambedkar Veedhi S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 HighCourt S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Legislators Home S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Mahatma Gandhi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Rajbhavan S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vidhana Soudha S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 CMM Court Complex S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Vasanthanagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560001 Bangalore G.P.O. Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore Corporation Building S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560002 Bangalore City S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Malleswaram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Palace Guttahalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Swimming Pool Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560003 Vyalikaval Extn S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Gavipuram Extension S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Mavalli S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Pampamahakavi Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Basavanagudi H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560004 Thyagarajnagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560005 Fraser Town S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 Training Command IAF S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560006 J.C.Nagar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Air Force Hospital S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560007 Agram S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 Hulsur Bazaar S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560008 H.A.L II Stage H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 Bangalore Dist Offices Bldg S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560009 K. G. Road S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Industrial Estate S.O (Bangalore) Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar IVth Block S.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA 560010 Rajajinagar H.O Bengaluru KARNATAKA -

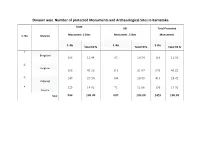

Division Wise Number of Protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka

Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka State ASI Total Protected S. No Division Monument / Sites Monument / Sites Monuments S. No S. No S. No Total TO % Total TO % Total TO % 1 Bangalore 105 12.44 63 10.34 168 11.56 2 Belgaum 365 43.25 311 51.07 676 46.52 3 249 29.50 164 26.93 413 28.42 Kalgurugi 4 125 14.81 71 11.66 196 13.51 Mysore Total 844 100.00 609 100.00 1453 100.00 Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka Bangalore Division Serial Per Total No. of Overall pre- Name of the District Number Total No. of cent Per protected protected ASI Total No. of Monument / Sites cent % Monument / protected Monument / Sites % Sites monuments 1 Bangalore City 7 2 9 2 Bangalore Rural 9 5 14 3 Chitradurga 8 6 14 4 Davangere 8 9 17 5 Kolara 15 6 21 6 Shimoga 12 26 38 7 Tumkur 29 6 35 8 Chikkaballapur 4 2 6 9 Ramanagara 13 1 14 Total 105 12.44 63 10.34 168 11.56 Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka Belgaum Division Total No. of Overall pre- Serial Per Name of the District Total No. of Per protected protected Number cent ASI Total No. of Monument / Sites cent % Monument / protected % Monument / Sites Sites monuments 10 Bagalkot 22 110 132 11 Belgaum 58 38 96 12 Vijayapura 45 96 141 13 Dharwad 27 6 33 14 Gadag 44 14 58 15 Haveri 118 12 130 16 Uttara Kannada 51 35 86 Total 365 43.25 311 51.07 676 46.52 Division wise Number of protected Monuments and Archaeological Sites in Karnataka Kalburagi Division Serial Per Total protected -

Prospectus 2021-2022

CENTRAL UNIVERSITY OF KARNATAKA CENTRAL UNIVERSITY OF KARNATAKA KALABURAGI PROSPECTUS 2021-2022 Admissions Through CU-CET 2021 - NTA www.cucet.nta.nic.in 1 - CUK PROSPECTUS 2021-2022 VISITOR Hon’ble President of India Shri Ram Nath Kovind CHANCELLOR Prof. N. R. Shetty VICE – CHANCELLOR Prof. Battu Satyanarayana CENTRAL UNIVERSITY OF KARNATAKA Aland Road, Kadaganchi, Kalaburagi – 585367, Karnataka, INDIA. Website: www.cuk.ac.in 2 - CUK PROSPECTUS 2021-2022 INDEX S. No Particulars Page No. 1 VICE- CHANCELLOR’S MESSAGE 05 2 CUCET NOTIFICATION & IMPORTANT DATES OF CUCET 2021 06-10 3 LIST OF CENTRAL UNIVERSITIES PARTICIPATING IN CUCET 2021 11 4 ABOUT THE UNIVERSITY 11 5 SPECIAL FEATURES & FACILITIES 12 6 ABOUT KALABURAGI&KALYANA KARNATAKA REGION 13 7 HOW TO REACH CUK 14 8 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2021-22 15 9 PROGRAMMES OFFERED 16-17 10 ELIGIBILITY CRITERIA FOR ADMISSION 18-27 11 EXAMINATION CENTRES OF CUCET-2021 28-31 12 RESERVATION POLICY IN ADMISSIONS 32-33 13 FEE STRUCTURE OF THE PROGRAMMES 34-35 14 FELLOWSHIPS, SCHOLARSHIPS AND STUDENTSHIPS 36 15 SCHOOLS AND DEPARTMENTS OF STUDIES 37-73 I SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND LANGUAGES Department of English Department of Kannada Department of Hindi Department of Linguistics Department of Foreign Language Studies Department of Music and Fine Arts II SCHOOL OF EDUCATION AND TRAINING Department of Education III SCHOOL OF EARTH SCIENCES Department of Geography Department of Geology IV SCHOOL OF SOCIAL & BEHAVIOURAL SCIENCES Department of Psychology Department of Social Work Department of History and Archeology -

District Census Handbook, Bidar, Part X-A, B, Series-14

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 SERIES-14 MYSORE DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK RAICHUR DISTRICT PART X-A: TOWN AND VILLAGE DIRECTORY PAR.T X-B: PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT P. l'ADMANABHA 01' THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE .SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS MYSORE 24 12 0 .:w L!!,' ~l-~~~~~~~~~048I'll!!!! , ' ,•• ~72 , MILES ii' Mlf~(o)D 20020 40 60 eo" 100 KILOMETRES ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISIONS, 1971 STATE BOUNDARY DISTRICT " TALUk " STATE CAPITAL * DISTRICT HEAIXWARTPS @ TAI..Uk o T. NuuIpu< - 'I'bltumakudIu Nonrolput Ho-Hoopet H_HubU ANDBRA PRADESH TAMIL NADU TUNGABHADRA DAM, MVNIRABAD (Motif on the Cover) The dam illustrated on the cover page is the one across the river Tungabhadra at Munirabad, Raichur District. It is situated at a distance of about 6 kms. from Hospet town of Bellary District. The main dam in masonry is 5,712 feet in length, with an earthen dam 500 feet and a composite dam 1,527 feet long. Its maximum height is 162 feet over the deepest foundations and its width is 93.50 feet. On the top of the dam is a roadway 22 feet wide. The spillway is designed for a maximum discharge of 6,50,000 cusecs through 33 lift type crest gates. The catchment area of the reservoir is 10,880 square miles. The capacity of the reservoir, which has a vast expanse of water spread area of over 146 square miles, is 133 T.M. cubic feet, and the area under irrigation by the project is 12·1 lakh acres, of which an extent of 8,10,000 acres lies in Mysore State and the rest in Andhra Pradesh.