3Bottov of ^Ffilotiopf)P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 Colonial Indian Architecture:A Historical Overview Debobrat Doley Research Scholar, Dept of History Dibrugarh University Abstract: The British era is a part of the subcontinent’s long history and their influence is and will be seen on many societal, cultural and structural aspects. India as a nation has always been warmly and enthusiastically acceptable of other cultures and ideas and this is also another reason why many changes and features during the colonial rule have not been discarded or shunned away on the pretense of false pride or nationalism. As with the Mughals, under European colonial rule, architecture became an emblem of power, designed to endorse the occupying power. Numerous European countries invaded India and created architectural styles reflective of their ancestral and adopted homes. The European colonizers created architecture that symbolized their mission of conquest, dedicated to the state or religion. The British, French, Dutch and the Portuguese were the main European powers that colonized parts of India.So the paper therefore aims to highlight the growth and development Colonial Indian Architecture with historical perspective. Keywords: Architecture, British, Colony, European, Modernism, India etc. INTRODUCTION: India has a long history of being ruled by different empires, however, the British rule stands out for more than one reason. The British governed over the subcontinent for more than three hundred years. Their rule eventually ended with the Indian Independence in 1947, but the impact that the British Raj left over the country is in many ways still hard to shake off. -

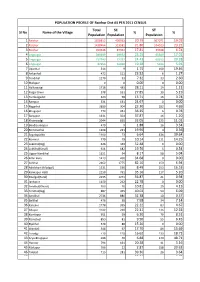

Sl No Name of the Village Total Population SC Population % ST

POPULATION PROFILE OF Raichur Dist AS PER 2011 CENSUS Total SC ST Sl No Name of the Village % % Population Population Population 1 Raichur 1928812 400933 20.79 367071 19.03 2 Raichur 1438464 313581 21.80 334023 23.22 3 Raichur 490348 87352 17.81 33048 6.74 4 Lingsugur 385699 89692 23.25 65589 17.01 5 Lingsugur 297743 72732 24.43 60393 20.28 6 Lingsugur 87956 16960 19.28 5196 5.91 7 Upanhal 514 9 1.75 100 19.46 8 Ankanhal 472 111 23.52 6 1.27 9 Tondihal 1270 93 7.32 33 2.60 10 Mallapur 0 0 0.00 0 0.00 11 Halkawatgi 1718 483 28.11 19 1.11 12 Palgal Dinni 578 161 27.85 30 5.19 13 Tumbalgaddi 423 58 13.71 16 3.78 14 Rampur 531 131 24.67 0 0.00 15 Nagarhal 3880 904 23.30 182 4.69 16 Bhogapur 773 281 36.35 6 0.78 17 Baiyapur 1331 504 37.87 16 1.20 18 Khairwadgi 2044 655 32.05 225 11.01 19 Bandisunkapur 479 9 1.88 16 3.34 20 Bommanhal 1108 221 19.95 4 0.36 21 Sajjalagudda 1100 73 6.64 436 39.64 22 Komnur 779 79 10.14 111 14.25 23 Lukkihal(Big) 646 339 52.48 0 0.00 24 Lukkihal(Small) 921 182 19.76 5 0.54 25 Uppar Nandihal 1151 94 8.17 58 5.04 26 Killar Hatti 1413 490 34.68 0 0.00 27 Ashihal 2162 1775 82.10 150 6.94 28 Advibhavi (Mudgal) 1531 130 8.49 253 16.53 29 Kannapur Hatti 2250 791 35.16 117 5.20 30 Mudgal(Rural) 2235 1271 56.87 21 0.94 31 Jantapur 1150 262 22.78 0 0.00 32 Yerdihal(Khurd) 703 76 10.81 29 4.13 33 Yerdihal(Big) 887 355 40.02 54 6.09 34 Amdihal 2736 886 32.38 10 0.37 35 Bellihal 476 38 7.98 34 7.14 36 Kansavi 1778 395 22.22 83 4.67 37 Adapur 1022 228 22.31 126 12.33 38 Komlapur 951 59 6.20 79 8.31 39 Ramatnal 853 81 9.50 55 -

Journal 16Th Issue

Journal of Indian History and Culture JOURNAL OF INDIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE September 2009 Sixteenth Issue C.P. RAMASWAMI AIYAR INSTITUTE OF INDOLOGICAL RESEARCH (affiliated to the University of Madras) The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road, Chennai 600 018, INDIA September 2009, Sixteenth Issue 1 Journal of Indian History and Culture Editor : Dr.G.J. Sudhakar Board of Editors Dr. K.V.Raman Dr. Nanditha Krishna Referees Dr. A. Chandrsekharan Dr. V. Balambal Dr. S. Vasanthi Dr. Chitra Madhavan Published by Dr. Nanditha Krishna C.P.Ramaswami Aiyar Institute of Indological Research The C.P. Ramaswami Aiyar Foundation 1 Eldams Road Chennai 600 018 Tel : 2434 1778 / 2435 9366 Fax : 91-44-24351022 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.cprfoundation.org ISSN : 0975 - 7805 Layout Design : R. Sathyanarayanan & P. Dhanalakshmi Sub editing by : Mr. Narayan Onkar Subscription Rs. 150/- (for 2 issues) Rs. 290/- (for 4 issues) 2 September 2009, Sixteenth Issue Journal of Indian History and Culture CONTENTS Prehistoric and Proto historic Strata of the Lower Tungabhadra Region of Andhra Pradesh and Adjoining Areas by Dr. P.C. Venkatasubbiah 07 River Narmada and Valmiki Ramayana by Sukanya Agashe 44 Narasimha in Pallava Art by G. Balaji 52 Trade between Early Historic Tamilnadu and China by Dr. Vikas Kumar Verma 62 Some Unique Anthropomorphic Images Found in the Temples of South India - A Study by R. Ezhilraman 85 Keelakarai Commercial Contacts by Dr. A.H. Mohideen Badshah 101 Neo trends of the Jaina Votaries during the Gangas of Talakad - with a special reference to Military General Chamundararaya by Dr. -

Price List of PUBLICATIONS 1939-2014

Price list of PUBLICATIONS 1939-2014 DECCAN COLLEGE POST-GRADUATE AND RESEARCH INSTITUTE (Deemed University) PUNE 411 006 (INDIA) (1) Terms & Conditions of Sale (This cancels our previous trade terms) Terms 1. Actual postal and packing charges to all orders received from outside India. 2. Postal and packing charges to be borne by the person/institution for all the orders upto Rs. 1000/- in India. 3. Free postal and packing charges to the orders above Rs. 1000/- one time. 4. No discount to individual buyers. 5. 20% discount on all the orders upto Rs. 500/-. 6. 25% discount on all the orders which exceeds Rs. 500/-. 7. Except educational and governmental institutions, books will be supplied ONLY on receipt of Advance Payment against Proforma Invoice. Conditions 1. Out-station buyers should remit the amount, either by M.O. or by Demand Draft drawn on any Nationalized Bank at Pune in the name of ‘Deccan College, Pune’. 2. For the convenience of both the supplier and the buyer and for the early delivery of the books, the books are usually supplied by Registered Book Post marked ‘Printed Books’. 3. Only bulk supply is made by roadways. 4. Books are supplied at buyer’s risk and supplier is not responsible for the books damaged, lost, etc., in transit as also for the delay in delivery of the books. 5. Books once sold and dispatched are not accepted back for any reason on exchanged for other parts. 6. Errors and omissions on the part of the supplier are accepted. 7. Books are not supplied by V.P.P. -

Subsistence Strategies and Burial Rituals: Social Practices in the Late Deccan Chalcolithic

Subsistence Strategies and Burial Rituals: Social Practices in the Late Deccan Chalcolithic TERESA P. RACZEK IN THE SECOND MILLENNIUM B.C., THE RESIDENTS OF THE WESTERN DECCAN region of India practiced an agropastoral lifestyle and buried their infant children in ceramic urns below their house floors. With the coming of the first millennium B.C., the inhabitants of the site of Inamgaon altered their subsistence practices to incorporate more wild meat and fewer grains into their diet. Although daily practices in the form of food procurement changed, infant burial practices remained constant from the Early Jorwe (1400 B.c.-lOOO B.C.) to the Late Jorwe (1000 B.c.-700 B.C.) period. Examining interments together with subsistence strategies firmly situates ideational practices within the fabric of daily life. This paper will explore the relationship between change and continuity in burial and subsistence practices around 1000 B.C. at the previously excavated Cha1colithic site of Inamgaon in the western Deccan (Fig. 1). By considering the act of burial as a moment of social construction that both creates and reflects larger traditions, it is possible to understand how each individual interment affects chronological variability. That burial traditions at Inamgaon were continuously recreated in the face of a changing society suggests that meaningful and significant practices were actively upheld. Burial practices at Inamgaon were both structured and fluid enough to allow room for individual and group expression. The con temporaneous variability that occurs in the burial record at Inamgaon may reflect the marking of various aspects of personhood. Burial traditions and the ability and desire of the living to conforITl to them vary over time and it is important to consider the specific social context in which they occur. -

Walking with the Unicorn Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia

Walking with the Unicorn Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia Jonathan Mark KenoyerAccess Felicitation Volume Open Edited by Dennys Frenez, Gregg M. Jamison, Randall W. Law, Massimo Vidale and Richard H. Meadow Archaeopress Archaeopress Archaeology © Archaeopress and the authors, 2017. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978 1 78491 917 7 ISBN 978 1 78491 918 4 (e-Pdf) © ISMEO - Associazione Internazionale di Studi sul Mediterraneo e l'Oriente, Archaeopress and the authors 2018 Front cover: SEM microphotograph of Indus unicorn seal H95-2491 from Harappa (photograph by J. Mark Kenoyer © Harappa Archaeological Research Project). Access Back cover, background: Pot from the Cemetery H Culture levels of Harappa with a hoard of beads and decorative objects (photograph by Toshihiko Kakima © Prof. Hideo Kondo and NHK promotions). Back cover, box: Jonathan Mark Kenoyer excavating a unicorn seal found at Harappa (© Harappa Archaeological Research Project). Open ISMEO - Associazione Internazionale di Studi sul Mediterraneo e l'Oriente Corso Vittorio Emanuele II, 244 Palazzo Baleani Archaeopress Roma, RM 00186 www.ismeo.eu Serie Orientale Roma, 15 This volume was published with the financial assistance of a grant from the Progetto MIUR 'Studi e ricerche sulle culture dell’Asia e dell’Africa: tradizione e continuità, rivitalizzazione e divulgazione' All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. Printed in England by The Holywell Press, Oxford This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com © Archaeopress and the authors, 2017. -

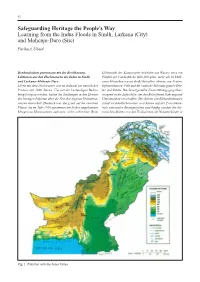

And Mohenjo-Daro (Site) Fariha A

62 Safeguarding Heritage the People’s Way Learning from the Indus Floods in Sindh, Larkana (City) and Mohenjo-Daro (Site) Fariha A. Ubaid Denkmalschutz gemeinsam mit der Bevölkerung. Höhepunkt der Katastrophe bedeckte das Wasser etwa ein Lektionen aus den Hochwassern des Indus in Sindh Fünftel der Landesfläche (800,000 qkm), mehr als 20 Milli- und Larkana–Mohenjo-Daro onen Menschen waren direkt betroffen, ebenso wie Ernten, Leben mit dem Hochwasser war im Industal ein natürlicher Infrastrukturen, Vieh und die bauliche Substanz ganzer Dör- Prozess seit 5000 Jahren. Um mit der beständigen Bedro- fer und Städte. Die bereitgestellte Unterstützung ging über- hung fertig zu werden, hatten die Siedlungen in den Ebenen wiegend in die Soforthilfe, um den Betroffenen Nahrung und des heutigen Pakistan über die Zeit ihre eigenen Verhaltens- Unterkunft zu verschaffen. Der Schutz von Kulturdenkmalen weisen entwickelt. Dennoch war das Land auf die enormen stand verständlicherweise weit hinten auf der Prioritäten- Fluten, die im Jahr 2010 zusammen mit bisher ungekannten liste nationaler Strategiepläne und häufig wurden die his- Mengen an Monsunregen auftraten, nicht vorbereitet. Beim torischen Stätten von den Evakuierten als Notunterkünfte in Fig. 1: Pakistan with the Indus Valley Safeguarding Heritage the People’s Way ... 63 Beschlag genommen. Der Wiederaufbau bedeutete vor allem die Errichtung neuer Häuser und Infrastruktur. Der Beitrag gibt einen Überblick über die Hochwasser- probleme und Vorsorgemaßnahmen bei den wichtigsten Denkmalstätten im Industal. Technisch-zivilisatorische Interventionen in die Landschaft, wie Dämme, Wehre, Ka- näle, Bewässerungssysteme und Hochwasserschutz-Vor- kehrungen, werden vor dem Hintergrund der historischen Bedeutung der Indus-Kulturen betrachtet. Mit einem der- art übergreifenden Blick wird für das Gebiet der heutigen Stadt Larkana und der benachbarten archäologischen Welterbestätte Mohenjo-Daro eine Analyse der Flutereig- nisse durchgeführt. -

Annual Report (2010-2011)

ANNUAL REPORT (2010-2011) Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute (Deemed University) Pune 411 006 ANNUAL REPORT (2010-2011) Edited by V.P. Bhatta V.S. Shinde Mrs. J.D. Sathe B. C. Deotare Mrs. Sonal Kulkarni-Joshi Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute (Declared as Deemed-to-be-University under Section 3 of U.G.C. Act 1956) Pune 411 006 Copies: 250 Issued on: August, 2011 © Registrar, Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research Institute (Deemed University) Pune 411 006 Published by: N.S. Gaware, Registrar, Deccan College, Post-Graduate and Research Institute (Deemed University) Pune 411 006 Printed by: Mudra, 383, Narayan Peth, Pune - 411030. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 6 AUTHORITIES OF THE INSTITUTE 7 GENERAL 9 SEVENTH CONVOCATION 13 DEPARTMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY I. Staff 46 II. Teaching 50 III. M.A. and P.G. Diploma Examination Results 54 IV. Ph.D.s Awarded 55 V. Ph.D. Theses 55 VI. Special Lectures Delivered in Other Institutions 62 VII. Research 67 VIII. Publications 107 IX. Participation in Conferences, Seminars, Symposia and Workshops 112 X. Other Academic Activities and professional and Administrative Services Rendered 121 XI. Nomination on Committees and Honours, Awards and Scholarships received 127 XII. Activities of the Discussion Group 128 XIII. Museum of Archaeology 130 MARATHA HISTORY MUSEUM I. Staff 133 II. Research Activities 133 III. Publication 133 IV. Other Academic Activities 133 V. Archival Activities 134 VI. Exhibition and Workshop 134 VII. Museum Activities 134 4 Annual Report 2010-11 DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS I. Staff 136 II. Teaching 137 III. M.A. Examination Results 139 IV. -

Death of the Aryan Invasion Theory by Stephen Knapp

Death of the Aryan Invasion Theory By Stephen Knapp With only a small amount of research, a person can discover that each area of the world has its own ancient culture that includes its own gods and legends about the origins of various cosmological realities, and that many of these are very similar. But where did all these stories and gods come from? Did they all spread around the world from one particular source, only to change according to differences in language and customs? If not, then why are some of these gods and goddesses of various areas of the world so alike? Unfortunately, information about prehistoric religion is usually gathered through whatever remnants of earlier cultures we can find, such as bones in tombs and caves, or ancient sculptures, writings, engravings, wall paintings, and other relics. From these we are left to speculate about the rituals, ceremonies, and beliefs of the people and the purposes of the items found. Often we can only paint a crude picture of how simple and backwards these ancient people were while not thinking that more advanced civilizations may have left us next to nothing in terms of physical remains. They may have built houses out of wood or materials other than stone that have since faded with the seasons, or were simply replaced with other buildings over the years, rather than buried by the sands of time for archeologists to unearth. They also may have cremated their dead, as some societies did, leaving no bones to discover. Thus, without ancient museums or historical records from the past, there would be no way of really knowing what the prehistoric cultures were like. -

Transboundary River Basin Overview – Indus

0 [Type here] Irrigation in Africa in figures - AQUASTAT Survey - 2016 Transboundary River Basin Overview – Indus Version 2011 Recommended citation: FAO. 2011. AQUASTAT Transboundary River Basins – Indus River Basin. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licencerequest or addressed to [email protected]. -

Tracing the Tradition of Sartorial Art in Indo-Pak Sub-Continen

TRACING THE TRADITION OF SARTORIAL ART IN INDO-PAK SUB-CONTINEN ZUBAIDA YOUSAF Abstract The study of clothing in Pakistan as a cultural aspect of Archaeological findings was given the least attention in the previous decades. The present research is a preliminary work on tracing the tradition of sartorial art in the Indo-Pak Sub-Continent. Once the concept of the use of untailored and minimal drape, and unfamiliarity with the art of tailoring in the ancient Indus and Pre Indus societies firmly established on the bases of early evidences, no further investigation was undertaken to trace the history of tailored clothing in remote antiquity. Generally, the history of tailored clothing in Indo-Pak Sub-Continent is taken to have been with the arrival of Central Asian nations such as Scythians, Parthians and Kushans from 2nd century BC and onward. But the present work stretches this history back to the time of pre-Indus cultures and to the Indus Valley Civilization. Besides Mehrgarh, Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, many newly exposed proto historic sites such as Mehi, Kulli, Nausharo, Kalibangan, Dholavira, Bhirrana, Banawali etc. have yielded a good corpus of researchable material, but unfortunately this data wasn’t exploited to throw light on the historical background of tailored clothing in the Indo-Pak Sub-Continent. Though we have scanty evidences from the Indus and Pre-Indus sites, but these are sufficient to reopen the discussion on the said topic. Keywords: Indus, Mehrgarh, Dholavira, Kulli, Mehi, Kalibangan, Harappa, Mohenjao- Daro, Clothing, Tailoring. 1 Introduction The traced history of clothing in India and Pakistan goes back to the 7th millennium BC. -

Architectural Features of the Early Harappan Forts

Ancient Punjab – Volume 8, 2020 103 ARCHITECTURAL FEATURES OF THE EARLY HARAPPAN FORTS Umesh Kumar Singh ABSTRACT What is generally called the Indus or the Harappan Civilization or Culture and used as interchangeable terms for the fifth millennium BCE Bronze Age Indian Civilization. Cunningham (1924: 242) referred vaguely to the remains of the walled town of Harappa and Masson (1842, I: 452) had camped in front of the village and ruinous brick castle. Wheeler (1947: 61) mentions it would appear from the context of Cunningham and Masson intended merely to distinguish the high mounds of the site from the vestiges of occupation on the lower ground round about and the latter doubt less the small Moghul fort which now encloses the police station on the eastern flank of the site. Burnes, about 1831, has referred to a ruined citadel on the river towards the northern side (Burnes 1834: 137). Marshall (1931) and Mackay (1938) also suspected of identifying Burnes citadel and Mackay (1938) had to suspend his excavations whilst in the act of examining a substantial structure which he was inclined to think was a part of city wall. Wheeler had discovered a limited number of pottery fragments from the pre- defense levels at Harappa in 1946 but the evidence was too meager to provoke serious discussion. The problem of origin and epi-centre of the Harappa Culture has confronted scholars since its discovery and in this context the most startling archaeological discoveries made and reported by Rafique Mughal (1990) is very significant and is a matter of further research work.