Shanghai Sketch and the Illustrated City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Cartoon in Transition: Animal Symbolism and Allegory from the “Modern Magazine” to the “Online Carnival”

Studies in Visual Arts and Communication: an international journal Vol 4, No 1 (2017) on-line ISSN 2393 - 1221 Chinese Cartoon in transition: animal symbolism and allegory from the “modern magazine” to the “online carnival” Martina Caschera* Abstract By definition, the cartoon (satirical, single-panelled vignette) “reduces complex situations to simple images, treating a theme with a touch of immediacy. A cartoon can mask a forceful intent behind an innocuous facade; hence it is an ideal art of deception” (Hung, 1994:124). As well as their western counterparts, Chinese cartoonists have always based much of their art on the strong socio-political potential of the format, establishing a mutual dependence of pictographic material and press journalism. From a media perspective, the present paper shows how Chinese cartoon developed from 1920s-1930s society ̶ when the “modern magazine” was the most important reference and medium for this newly-born visual language – to the present. Cyberspace has recently become the chosen space for Chinese cartoonists’ visual satire to take part in an international public discourse and in the “online carnival” (Herold and Marolt, 2011:11-15), therefore replacing magazines and printed press. Through emblematic exempla and following the main narrative of “animal symbolism and allegory”, this paper intends to connect the historical background with cartoonists’ critical efficiency, communicative tools and peculiar aesthetics, aiming at answering to questions such as: how Chinese modern cartoon changed, from the first exempla conveyed in “modern magazines” to the latest online expressions? Is its original power of irreverence still alive and how did it survive? How modern cartoonists (Lu Shaofei, Liao Bingxiong) and contemporary cartoonists (Rebel Pepper, Crazy Crab, Ba Diucao) have been dealing with governmental intervention and censorship? Keywords: Visual Culture, Popular Culture, cartoon, satire, censorship, cyberspace Introduction of a top-down indoctrination3. -

MANHUA MODERNITY HINESE CUL Manhua Helped Defi Ne China’S Modern Experience

CRESPI MEDIA STUDIES | ASIAN STUDIES From fashion sketches of Shanghai dandies in the 1920s, to phantasma- goric imagery of war in the 1930s and 1940s, to panoramic pictures of anti- American propaganda rallies in the 1950s, the cartoon-style art known as MODERNITY MANHUA HINESE CUL manhua helped defi ne China’s modern experience. Manhua Modernity C TU RE o ers a richly illustrated and deeply contextualized analysis of these il- A lustrations from the lively pages of popular pictorial magazines that enter- N UA D tained, informed, and mobilized a nation through a half century of political H M T and cultural transformation. N H O E A “An innovative reconceptualization of manhua. John Crespi’s meticulous P study shows the many benefi ts of interpreting Chinese comics and other D I M C illustrations not simply as image genres but rather as part of a larger print E T culture institution. A must-read for anyone interested in modern Chinese O visual culture.” R R I CHRISTOPHER REA, author of The Age of Irreverence: A New History A of Laughter in China L N “A rich media-centered reading of Chinese comics from the mid-1920s T U U I I through the 1950s, Manhua Modernity shifts the emphasis away from I R R T T ideological interpretation and demonstrates that the pictorial turn requires T N N examinations of manhua in its heterogenous, expansive, spontaneous, CHINESE CULTURE AND THE PICTORIAL TURN AND THE PICTORIAL CHINESE CULTURE Y and interactive ways of engaging its audience’s varied experiences of Y fast-changing everyday life.” YINGJIN ZHANG, author of Cinema, Space, and Polylocality in a Globalizing China JOHN A. -

Fall 20 17 Newsletter

FALL 2017 NEWSLETTER May 2017 U-M Rogel China Trip: From left, Xinjiang landscape; Richard Rogel, Professor Emeritus Kenneth Lieberthal and LSA Dean Andrew Martin in Xinjiang, China; Yurts in Xinjiang. Photos courtesy of Tom Baird. Mary Gallagher e start off this new academic year with many changes. First and LRCCS Director foremost, the LRCCS has moved from the School of Social Work WBuilding to the 4th Floor of Weiser Hall, which we share with the other Asian centers at the International Institute. We are excited about this move as it allows us to offer space to our postdoctoral fellows and distinguished visitors. We will also be able to host research seminars and workshops on the 4th Floor. When the building is completely finished later in the fall, there will be event space on the 10th floor. Please come and visit us to see our new digs! The move has also compelled us to shift the time (and title) of our Noon Lecture Series (NLS) on Tuesdays. The Tuesday Lecture Series (TLS) will now be held from 11:30 to 12:30 instead of 12 PM to 1 PM in order to accommodate classes that begin at 1 PM. We hope this change is not too troublesome to the community. It may even allow our faculty to stay for the whole lecture, as we also often need to dash out for a 1 PM class. This year we welcome a new crop of postdoctoral fellows: University of Michigan University Elizabeth Berger, Jeffrey Javed, Lei Duan, and Anne Rebull. We also have several visiting scholars from China, hosted by Ming Xu in the School for Environment and Sustainability, San Duanmu in Linguistics, David Rolston in ALC, and myself. -

Humour in Chinese Life and Culture Resistance and Control in Modern Times

Humour in Chinese Life and Culture Resistance and Control in Modern Times Edited by Jessica Milner Davis and Jocelyn Chey A Companion Volume to H umour in Chinese Life and Letters: Classical and Traditional Approaches Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Hong Kong University Press 2013 ISBN 978-988-8139-23-1 (Hardback) ISBN 978-988-8139-24-8 (Paperback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Limited, Hong Kong, China Contents List of illustrations and tables vii Contributors xi Editors’ note xix Preface xxi 1. Humour and its cultural context: Introduction and overview 1 Jessica Milner Davis 2. The phantom of the clock: Laughter and the time of life in the 23 writings of Qian Zhongshu and his contemporaries Diran John Sohigian 3. Unwarranted attention: The image of Japan in twentieth-century 47 Chinese humour Barak Kushner 4 Chinese cartoons and humour: The views of fi rst- and second- 81 generation cartoonists John A. Lent and Xu Ying 5. “Love you to the bone” and other songs: Humour and rusheng 103 rhymes in early Cantopop Marjorie K. M. Chan and Jocelyn Chey 6. -

The Transformation of Guai Imagery in China (1949-78)

The Transformation of Guai Imagery in China (1949-78) VolumeⅡ: Figure Sijing Chen A thesis submitted to Birmingham City University in part fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2017 Faculty of Arts, Design and Media, Birmingham City University Figure Figure 1.1. Taotie 饕餮 pattern in the middle Shang dynasty, illustrated in Li Song 李 松 (2011), Chinese Bronze Ware. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 95. Figure 1.2. Zhenmu shou 镇墓兽, Tang Dynasty, unearthed in 1957, Xi’an 西安, Shanxi Province, pottery, height 63.2 cm, width 67.5 cm. The collection of Historical Times, the National Museum of China, Beijing. Figure 1.3. The Ten Kings of Hell Sutra (a detail), late 9th-early 10th century CE, ink and pigment on paper, height 28 cm. The collection of Chinese Religious Paintings, the British Museum, London. Figure 1.4. Xiyou ji 西游记 (Journey to the West), printed on paper. Illustrated in Zhang Mangong 张满弓 (2004), Gudian wenxue banhua 古典文学版画 (Classical Literature Prints). Kaifeng: Henan University Press, p. 15. Figure 1.5. The snake guai fighting Monkey King is shown in the block-printed book of Journey to the West in Ming Dynasty. Illustrated in Li Zhuowu 李卓吾 (Ming Dynasty), Li Zhuowu xiansheng piqing Xiyou ji 李 卓 吾先生批 评西游记 (Mr. Li Zhuowu’s Comments on Journey to the West). Anhui Library, Hefei. Figure 1.6. Jiang Yinggao 蒋 应镐 , Bibi 獙獙, Ming Dynasty, printed on paper. Illustrated in Guo Pu 郭璞 (c. 1573-1620 CE), Shanhai jing zhu 山海经注 (Explanatory Notes of The Classic of Mountains and Seas). -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Shanghai's Wandering

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Shanghai’s Wandering Ones: Child Welfare in a Global City, 1900–1953 DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in History by Maura Elizabeth Cunningham Dissertation Committee: Professor Jeffrey N. Wasserstrom, Chair Professor Kenneth L. Pomeranz Professor Anne Walthall 2014 © 2014 Maura Elizabeth Cunningham DEDICATION To the Thompson women— Mom-mom, Aunt Marge, Aunt Gin, and Mom— for their grace, humor, courage, and love. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF TABLES AND GRAPHS v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi CURRICULUM VITAE x ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xvii INTRODUCTION: The Century of the Child 3 PART I: “Save the Children!”: 1900–1937 22 CHAPTER 1: Child Welfare and International Shanghai in Late Qing China 23 CHAPTER 2: Child Welfare and Chinese Nationalism 64 PART II: Crisis and Recovery: 1937–1953 103 CHAPTER 3: Child Welfare and the Second Sino-Japanese War 104 CHAPTER 4: Child Welfare in Civil War Shanghai 137 CHAPTER 5: Child Welfare in Early PRC Shanghai 169 EPILOGUE: Child Welfare in the 21st Century 206 BIBLIOGRAPHY 213 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Frontispiece: Two sides of childhood in Shanghai 2 Figure 1.1 Tushanwan display, Panama-Pacific International Exposition 25 Figure 1.2 Entrance gate, Tushanwan Orphanage Museum 26 Figure 1.3 Door of Hope Children’s Home in Jiangwan, Shanghai 61 Figure 2.1 Street library, Shanghai 85 Figure 2.2 Ah Xi, Zhou Ma, and the little beggar 91 Figure 3.1 “Motherless Chinese Baby” 105 Figure -

The Transformation of Guai Imagery in China (1949-78)

The Transformation of Guai Imagery in China (1949-78) VolumeⅠ: Text Sijing Chen A thesis submitted to Birmingham City University in part fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2017 Faculty of Arts, Design and Media, Birmingham City University Abstract Guai are bound up with Chinese traditional culture, and have been presented via various cultural forms, such as literature, drama, New Year print and costume. Indeed, guai imagery has played a significant role in the definition and development of traditional Chinese visual culture. Throughout history, guai visual products reflected national values, aesthetic appreciation and philosophical aspirations. Nevertheless, in twentieth-century China, political, social and religious transitions have changed the traditional role of guai imagery. Particularly, from the year 1949 when the People’s Republic of China was founded to 1978 when economic reform and the Open Door Policy were introduced, guai visual production was under Mao’s artistic control nationwide, and its political functions became dominant. Traditional guai imagery was politically filtered and modified to satisfy both Mao and the Communist Party’s political aspirations and the public aesthetic. This research examines the transformation of guai imagery formally and symbolically in the Chinese aesthetic and cultural context from 1949 to 1978, and builds knowledge to evaluate and understand the production, dissemination and perception of guai visual products in this period. It provides a contribution to the understanding of the inherent values of guai and how the reinterpretation of guai imagery that reflects political, social and cultural values in Chinese visual art. Acknowledgments I wish to thank all those who supported this study. -

Searchable PDF Format

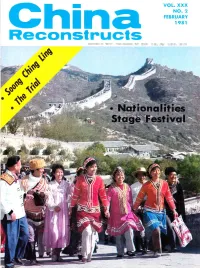

Australia: A S0 72 New Zealand: NZ S0 8:+ U K:39p U S A: S0 7E Red Rocks and Green Stream Set Ofl Each Other. l'raditional Cltirtt'yc puirtting ht Shi br PUBLISHED MONTHTY lll..FNG!!-S_!:1,_-FRENCH, SPAN_ISH,_ARABIC, GERMAN, PORTUGUESE AND cHrNEsE By THE CHINA WETFARE lNsflrurE isooNa' aHiNa"''riNd'-ti#\I[iriil, vot. xxx No.2 FEBRUARY T981 Articles of the Month Recolling One of Our Founders CONTENTS 5oon9 Ching Ling writes of lormer Politics/Low editoriol boord choirmon Jin .Zhong. huo, hounded Recalling One of Our Founders 2 to deqth by membeis of the gong ol 2 Historic Trial: lnside and Outside the Courtroom 4 four. Poge Notionolities Festival of Minority Song and Dance I Visitors' Views on the Festival 15 lnside ond Outside the Courtroom Economy Giant Project on the Changjiang (Yangtze) 20 At the triol lor Diversified Economy in 'Earthly Paradise' 30 mojor crimes ol Growing Rubber in Colder Climates 48 the ten princi. Pol members Society of the Lin Bioo- Employment and Unemployment 25 Jiong QinE cli- How One City Provided Jobs for All 28 ques. Poge I Salvaging Ships in the South China Sea 38 Foreign Commerce First U S. Trade Exhibition in China 35 Stort on Hornessing the Culture/Medio Chongjiong (Yongtze) River The Old Summer Palace, Yuan Ming Yu6n 40 China's Animated Cartoon Films 45 'Radio Peking' and lts Listeneis 57 Ihe lorgest woter conservotion Children's Books by the Hundred Million bb ond on Medicine Chino ted neor i ing Encyclopedia of Chinese Medicine 53 from uc. -

In Search of Laughter in Maoist China: Chinese Comedy Film 1949-1966

IN SEARCH OF LAUGHTER IN MAOIST CHINA: CHINESE COMEDY FILM 1949-1966 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Ying Bao, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Kirk A. Denton, Adviser Professor Mark Bender Professor J. Ronald Green _____________________ Professor Patricia Sieber Adviser East Asian Languages and Literatures Graduate Program Copyright by Ying Bao 2008 ABSTRACT This dissertation is a revisionist study examining the production and consumption of comedy film—a genre that has suffered from relative critical and theoretical neglect in film studies—in a culturally understudied period from 1949 to 1966 in the People’s Republic of China. Utilizing a multidisciplinary approach, it scrutinizes the ideological, artistic, and industrial contexts as well as the distinctive textures of Chinese comedy films produced in the so-called “Seventeen Years” period (1949-1966). Taking comedy film as a contested site where different ideologies, traditions, and practices collide and negotiate, I go beyond the current canon of Chinese film studies and unearth forgotten films and talents to retrieve the heterogeneity of Chinese cinema. The varieties of comedy examined—mostly notably the contemporary social satires in the mid-1950s, the so- called “eulogistic comedies,” and comedian-centered comedies in dialect and period comedies, as well as lighthearted comedies of the late 1950s and the early 1960s— problematize issues of genre, modernity, nation, gender, class, sublimity, and everyday ii life in light of the “culture of laughter” (Bakhtin) within a heavily politicized national cinema. -

Representations of Children in the Work of the Cartoon Propaganda Corps During the Second Sino-Japanese War

“Chinese Children Rise Up!”: Representations of Children in the Work of the Cartoon Propaganda Corps during the Second Sino-Japanese War Laura Pozzi, European University Institute Abstract During the War of Resistance against Japan (1937–1945), children were a major subject of propaganda images. Children had become significant figures in China when May Fourth intellectuals, influenced by evolutionary thinking, deemed “the child” as a central figure for the modernization of the country. Consequently, during the war, cartoonists employed already- established representations of children for propagandistic purposes. By analyzing images published by members of the Cartoon Propaganda Corps in the wartime magazine Resistance Cartoons, this article shows how portrayals of children fulfilled symbolic as well as normative functions. These images provide us with information about the symbolic power of representations of children, and about authorities’ expectations of China’s youngest citizens. However, cartoonists also created images undermining the heroic rhetoric often attached to representations of children, especially after the dismissal of the Cartoon Propaganda Corps in 1940. This was the case with cartoonist Zhang Leping’s (1910–1992) sketches of “Zhuji after the Devastation,” which revealed the discrepancies between propagandistic representations and children’s everyday life in wartime China. Keywords: Second Sino-Japanese War, War of Resistance, history of childhood, cartoons, propaganda, Cartoon Propaganda Corps, Zhang Leping Introduction Who killed your parents? Who killed your sisters? Who pierced our brothers with a bayonet? Who seized our lands and properties? We should go and fight against them! Old people, middle-aged people, young people, it’s time to rise up! You little masters of the New China, rise up! Sing on the street corners, put a play on the stage, transport the wounded from the battlefield, display posters on whitewashed walls. -

The Cartoonist Hu Kao and Shanghai Modeng

Paul Bevan 1 TTTHE CCCARTOONIST HHHU KKKAO AND SSSHANGHAI MMMODENG In an article written for the January 1939 edition of the English language journal Asia , Trinidadian born journalist, Jack Chen (1908-1995), described Hu Kao (1912-1994) as ‘one of the finest of our young modern artists.’ 2 Chen’s approbation of Hu’s work had been repeated time and again in articles promoting the exhibitions of ‘Modern Chinese Pictorial Art’ he had taken to Europe, the USA and China during 1937/38 (Chen 1939). 3 Hu Kao had already made a name for himself in Shanghai as a cartoonist and illustrator, having begun his career at the age of 20. A year after is escape from war-torn Shanghai in 1937, he made his way with Jack Chen, via Hong Kong to the Communist base in Yan’an, were he took up a teaching post at the newly established Lu Xun Academy. The left-wing cartoon movement of wartime China to which Hu belonged remains largely unknown in the West. In China, Hu has been overshadowed by China’s cartoon greats: Ye Qianyu (1907-1995), Ding Cong (1916-2009) and Zhang Leping (1910-1992). EARLY WORK 1933 ---1934-1934 Hu Kao’s early work had appeared in popular cartoon magazines such as Shidai manhua (Modern Sketch) 4 and Lunyu 5 where his ‘art-deco’ inspired humorous cartoons and sketches depicted well-known Chinese film stars, sports personalities and politicians. 1 Paul Bevan studied for his MA degree in Chinese art at the School of Oriental and African Studies where he is currently a Research Student in the Faculty of Languages and Cultures researching on “ Manhua and Illustrated Propaganda in Wartime China 1927-1945”. -

HEC EN Thesis Cover and Title Pages

The Revolution of a Little Hero: The Sanmao Comic Strips and the Politics of Childhood in China, 1935-1962 Laura Pozzi Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 7 July 2014 I European University Institute Department of History and Civilization The Revolution of a Little Hero: The Sanmao Comic Strips and the Politics of Childhood in China, 1932-1965 Laura Pozzi Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Stephen A. Smith, (EUI/All Souls College, University of Oxford) Prof. Dirk Moses, (EUI) Prof. Barbara Mittler, (University of Heidelberg) Prof. Harriet Evans, (University of Westminster) © Laura Pozzi, 2014 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author III IV ABSTRACT This thesis analyses the production, content and development of cartoonist Zhang Leping's Sanmao comic strips between 1935 and 1962 in the context of the growing political and cultural significance of childhood in twentieth century China. After years of wars and dramatic political changes, Sanmao is still a recognizable visual icon in China today, and his lasting popularity makes him an interesting case-study for understanding the development of cartoon art and the political deployment of the image of the 'child' in China over the twentieth century. This thesis investigates two main problems: firstly, it aims to analyze how through his strips Zhang Leping intervened in contemporary debates about the significance and role of children in the development of the Chinese nation; secondly, it follows the transformation of fictional child-hero Sanmao from a commentator on contemporary China in the early 1930s into a sustainer of the Chinese Communist Party after 1949.