BIOGRAPHICAL SUMMARY: Roland Dacoscos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Āinahau: the Genealogy of Ka'iulani's Banyan

ralph thomas kam The Legacy of ‘Āinahau: The Genealogy of Ka‘iulani’s Banyan “And I, in her dear banyan shade, Look vainly for my little maid.” —Robert Louis Stevenson ‘Āinahau, the home of Archibald Scott Cleghorn, his wife, Princess Miriam Kapili Likelike and their daughter, Princess Victoria Ka‘iu- lani, no longer stands, the victim of the transformation of Waikīkī from the playground of royalty to a place of package tours, but one storied piece of its history continues to literally spread its roots through time in the form of the ‘Āinahau banyan. The ‘Āinahau ban- yan has inspired poets, generated controversy and influenced leg- islation. Hundreds of individuals have rallied to help preserve the ‘Āinahau banyan and its numerous descendants. It is fitting that Archibald Cleghorn (15 November 1835–1 Novem- ber 1910), brought the banyan to Hawai‘i, for the businessman con- tinued the legacy of the traders from whom the banyan derives it etymology. The word banyan comes from the Sanskrit “vaniyo” and originally applied to a particular tree of this species near which the traders had built a booth. The botanical name for the East Indian fig tree, ficus benghalensis, refers to the northeast Indian province of Ralph Kam holds an M.A. and a Ph.D. in American Sudies from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and an M.A. in Public Relations from the University of Southern California. The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 45 (2011) 49 50 the hawaiian journal of history Bengal, now split between India and Bangladesh. That the tree was introduced in Hawai‘i after Western contact is reflected in its Hawai- ian name: “paniana,” a transliteration of the English word. -

Waikīkī Wiki Wiki Wire

Volume IX, No. 41 Waikīkī Improvement Association October 9—15, 2008 Waikīkī Wiki Wiki Wire Sheraton Princess Ka‘iulani To Host The 14th Annual Hana Ho‘ohiwahiwa ‘O Ka‘iulani Weeklong Series of Events to be Held in Honor of Princess Ka‘iulani In a true fashion befitting royalty, the Sheraton Princess Ka`iulani will host a week of various Hawaiian cultural events called Hana Ho`ohiwahiwa `O Ka`iulani (to celebrate and honor Ka`iulani), honoring the legacy and birthday of its namesake, Princess Victoria Ka`iulani October 12 – 18. This year, Sheraton Princess Ka`iulani will be offering visitors and residents an opportunity to participate in the following fun and educational activities: Sunday, October 12 Hula Lessons with Kealoha Pau`ole at the Dolphin Lanai at 1:00 p.m. Monday, October 13 Feather Flower Lei Making with Nathan White at the Dolphin Lanai at 2 p.m. Tuesday, October 14 Hawaiian Quilting Lessons with Aunty Daisy and Kupuna at the Dolphin Lanai at 2 p.m. Wednesday, October 15 Fresh Flower Lei Making with Nathan White at the Dolphin Lanai at 2 p.m. Thursday, October 16 – Princess Ka`iulani’s Birthday Presentation of the Princess Ka`iulani Collection by Hawaiian Island Stamp & Coin at the Main Lobby from 8 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Princess Ka`iulani Elementary School Performance at the Lava Rock Stage at 4:30 p.m. Royal Court Procession by Tihati Productions from the Ainahau Lobby to the Princess Wing at 5:00 p.m. Birthday Cake Cutting at the Dolphin Lanai at 5:30 p.m. -

STORY by NATE CHINEN > PHOTOS by MEGAN SPELMAN

STORY BY NATE CHINEN • PHOTOS BY MEGAN SPELMAN 47 String Band Revival t a glance it isn’t the like- guitar and Helm on second ‘ukulele, liest setting for a royal suggests a courtly strain of classical parlor Aassembly: a plastic folding music—but it also sounds proudly and table on a concrete-floor länai, cheap unmistakably Hawaiian. At the finish there Christmas lights strung along the eaves. are peals of laughter, punctuated by a But the musicians gathered around the playful “Yee-haw!” table one February evening in the Hawaiian Mahi, Helm and the others have recon- homestead neighborhood of Papakölea are vened here, at the Asing family home, conjuring old sounds of princely pedigree a few weeks after “A Night of Sovereign with the rare, transporting enchantment Strings: Celebrating the Musical Legacy of of a seance. Mekia Albert Kealakai,” an ambitious The song sparking this reverie is “Moani musical program at the Honolulu Museum ke ‘Ala,” composed by Prince William Pitt of Art’s Doris Duke Theatre. The concert, Leleiohoku in the 1870s—possibly during which was rapturously received during the early reign of his brother, King David two sold-out performances in January, Kaläkaua. A flute and two violins introduce sought to re-create the sound and spirit of the jaunty theme, over the oompah strut late-nineteenth-century Hawaiian music, of upright bass and cello. Strumming which drew from European classical a percussive upbeat on ‘ukulele is Aaron models without losing its root connections Mahi, the esteemed former maestro of the to hula, mele (songs) and ‘ölelo Hawai‘i Honolulu Symphony and the Royal Hawai- (Hawaiian language). -

Broken Trust

Introduction to the Open Access Edition of Broken Trust Judge Samuel P. King and I wrote Broken Trust to help protect the legacy of Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop. We assigned all royal- ties to local charities, donated thousands of copies to libraries and high schools, and posted source documents to BrokenTrustBook.com. Below, the Kamehameha Schools trustees explain their decision to support the open access edition, which makes it readily available to the public. That they chose to do so would have delighted Judge King immensely, as it does me. Mahalo nui loa to them and to University of Hawai‘i Press for its cooperation and assistance. Randall W. Roth, September 2017 “This year, Kamehameha Schools celebrates 130 years of educating our students as we strive to achieve the thriving lāhui envisioned by our founder, Ke Ali‘i Bernice Pauahi Bishop. We decided to participate in bringing Broken Trust to an open access platform both to recognize and honor the dedication and courage of the people involved in our lāhui during that period of time and to acknowledge this significant period in our history. We also felt it was important to make this resource openly available to students, today and in the future, so that the lessons learned might continue to make us healthier as an organization and as a com- munity. Indeed, Kamehameha Schools is stronger today in governance and structure fully knowing that our organization is accountable to the people we serve.” —The Trustees of Kamehameha Schools, September 2017 “In Hawai‘i, we tend not to speak up, even when we know that some- thing is wrong. -

Nsn 12-12-12

IS BUGG “E Ala Na Moku Kai Liloloa” • D AH S F W R E E N E! Haleiwa Flower Shop E • R Retires S O I N H C see page 17 S E H 1 T 9 R 7 O 0 N NORTH SHORE NEWS December 12, 2012 VOLUME 29, NUMBER 24 Turtle Bay Resort Shares Draft SEIS After hundreds of meetings ment approvals for up to 3,500 pact findings and solutions, as with North Shore stakeholders units, including five hotel sites. well as the resort’s commitment and residents, Turtle Bay Resort Today’s owners have voluntarily to continued responsible steward- published its Draft Supplemental reduced this to only 1,375 units, ship. Environmental Impact Statement with only two new hotels, scal- A 45-day public comment on Nov. 23. ing back more than 60 percent period follows publication of the The 1,635-page document de- of density and preserving over Draft SEIS. However, because Tur- tails the resort’s commitment to 75 percent of their total land for tle Bay Resort wants to receive as a balanced approach to develop- open space. many comments as possible, the ment and the reports of respected Within this issue of the North comment period was voluntarily third party experts. In 1986, the Shore News, an insert details extended to Jan. 18. See the insert previous owners received govern- many of the document’s key im- for more detailed information. PROUDLY PUBLISHED IN Permit No. 1479 No. Permit Hale‘iwa, Hawai‘i Honolulu, Hawaii Honolulu, U.S. POSTAGE PAID POSTAGE U.S. -

Hawai'i Edible Book Contest

The Newsletter for UH Manoa Library Issue 21 • SPRING 2014 KE KUKINI the messenger The Newsletter for UH Mānoa Library Issue 21 • SPRING 2014 Photos from the HAWAI‘I EDIBLE 5TH Annual BOOK CONTEST EMBEDDED LIBRARIAN – PACIFIC ISLANDS STUDIES 401, CAPSTONE CLASS By Kealiʻi MacKenzie This semester I have the privilege of volunteering my time as the embedded librarian for Professor Lola Bautista’s PACS 401 class where students have a capstone project which combines research with service learning. The class consists of ten students from various backgrounds and connec- tions to the Pacific region. Late in the fall 2013 semester, Professor Lola contacted me about aiding her students with the research component of their projects. In spring 2013 I was one of Professor Lola’s students in the graduate level course PACS 603, Researching Oceania. She also knew that I not only have my MLISc from the University of Hawaiʻi, but also work as a part time reference librarian in the Hawaiian and Pacific collections. Professor Lola and I worked out what my role would be for the class, and on the advice of Stu Dawrs and Eleanor Kleiber, arrived at the designation of embedded librarian. As my current position in the library is solely for reference in the Hawaiian and Pacific collections, my work as an embedded librarian is volunteer service. Luckily, it has many benefits: first, and most importantly, I am able to assist and build relationships with students as they conduct research, I am strengthening my instruction skills, and I have expanded my own knowledge of different topics related to Pacific studies. -

Men of Hawaii" to the Public a Public Considerably Wider Than the Bounds of - - the Territory Its Editors and Publishers Have a Two- Fold Purpose

1AWAB BEflNQ A LIBRARY, COMPLETE AND AUTHENTBC, OF THE MEH OF IEVEM EDITED BY JOHN WILLIAM SIDDALL PUBLISHED BY HONOLULU STAR-BULLETIN, LIMITED TERRITORY OF HAWAII 1917 t -> ' 87427V T % ' - > * COPYRIGHT. 1917 HONOLULU STAR-BULLETIN, LTD. HONOLULU. HAWAII N PRESENTING "Men of Hawaii" to the public a public considerably wider than the bounds of - - the Territory its editors and publishers have a two- fold purpose. First, the book is a standard reference work, compre- hensive, complete and authoritative. It is a publication compiled with a care and a system of collecting information which in- sures its accuracy and insures also that justice is done to its subject. It is a reference volume presenting biographically pertinent facts about the men of Hawaii who lead in their respective fields. In general these fields are the business or commercial, the professional, the educational, the religious and the scientific covering all activities which in Hawaii have brought its men to the front as potent and constructive factors in their communities. Secondly, the book is a series of milestones of achieve- ments. It has been truly said that the progress of any gener- ation, of any century, of any country, of any nation may be measured by the biographies of its men. In Hawaii this is true today as in ancient Greece, medieval Rome, modern France, or England, or the mainland United States. Hawaii is a modern American community with its roots far back in the past. Here the primitive life of Polynesia has been moulded and modified by the influx of many races, bloods and languages. -

Waikiki Wiki-Wiki Wire

Volume V, No. 41 Waikiki Improvement Association Oct. 14 — Oct. 21, 2004 Waikiki Wiki-Wiki Wire Aloha Drive Park Plan This week the City un- veiled the design for the park and parking facility pro- posed for Aloha Drive. In 2003, the city condemned the vacant 33,000-square- foot property at Seaside Avenue and Aloha Drive, one block mauka of Kuhio Avenue, for approximately $2.3 million. The site is temporarily being used as a base yard for Kuhio Avenue Construction. Nearby residents asked the city to stop a proposed senior living apartment building and support the park and parking plan. The origi- The Park is 21,000-square-feet nal project concept included a with landscaping and 40 new trees. parking facility with approximately It includes a children’s play area and a black ornamental fence. The 80 stalls, but to save the cost of Inside this issue: constructing the structure the city project is scheduled to go out to bid decided on a surface park with 48 later this month or early November Aloha Drive Park Plan 1 diagonal parking spaces around for awarding in December. The the perimeter. When the existing estimated completion date is third Brunch on the Beach 2 street parking is factored in, there quarter 2005. The total cost of de- is a net 35 additional parking sign and construction is approxi- Princess Kaiulani Celebration 2 spaces. mately $1 million. Beach Cleanup on Oct. 23rd 2 The Royal Hawaiian Band 2 Masters of the Palate 3 Film Festival Coming to Sunset 3 on the Beach Queen’s Tour of the Waikiki 3 Historic Trail Other Waikiki Events 4 Kuhio Beach Torch Lighting 4 and Hula Show Brunch on the Beach, October 17th Brunch on the Beach returns For informa- this Sunday, October 17, 9:00AM - tion call the City 1:30PM, featuring musical artist and County of Jake Shi- Honolulu at mabukuro! (808) 523-CITY Once (2489) or the again, Waikiki Improve- Brunch on ment Association the Beach at (808) 923- will trans- 1094. -

Tour the Waikiki Aquarium ($8 Entry Fee with Student ID)

Tour the Waikiki Aquarium ($8 entry fee with student ID). Snorkel at Hanauma Bay and see the Humuhumunukunukuapua’a ($7.50 entry, free for Hawaiian residents). Visit the Honolulu Zoo ($8 entry fee with student ID). Race through the "World's Largest Maze" at Dole Plantation (tour prices range from $4-8.75 with student ID). Look for humpback whales (November through April off Makapuu or Kaena Point). Boogie board "The Wall" in Waikiki or at Waimanalo Beach. Hike to Manoa Falls and experience what it’s like to be in “Jurassic Park.” Count the waterfalls along the H3. Check out the new International Market in Waikiki. Hike to the top of Diamond Head ($1 entry fee). Relax under a tree at Kakaako Waterfront Park. Take a study break and nap under the trees at Fosters Botanical Garden ($3 entry fee for Hawaiian residents). Hike up to the Makapuu lighthouse. Visit Kailua and Lanikai and do the “pillbox hike.” Visit the Oceanarium Restaurant at Pacific Beach Hotel. Swim alongside the honu (turtle) at any of Oahu's 139 beaches. Walk to Goat Island in Laie to explore the tide pools in low tide. Hike the Maunawili Trail. Pick wild ginger, hibiscus and plumeria along the side of the road. Watch the Friday night sail boat races from Magic Island at Ala Moana Beach Park. Visit Waimea Bay on the North Shore. Explore the tide at Shark's Cove, named for its shape, not its inhabitants! Go see UH Manoa's School of Architecture hold their sand castle building contest in February. -

Men of Hawaii a Biographical Reference

...._._.-—vA9:-—.:~ MEN OF HAWAII A biographical record of men of substantial achievement in the Hawaiian Islands VOLUME IV Revised Edited by GEORGE F. NELLIST Published by THE HONOLULU STAR-BULLETIN, LTD. Territory of Hawaii I 9 3 O av .M.n.., ;w»$. _._.fim..sm«._ us. 2..M... 9.3%..3;.sfl.. Copyright, 1930, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, Limited Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii. U.S.A. FOREWORD “ EN OF HAWAII,’ is the fourth volume of bio graphical records in the regular series which has been published, beginning with l9l7, by The Honolulu Star Bulletin. This series aims to make available for the present, and to preserve for the future, the life stories of leaders in various fields of the Hawaiian Islands. It is a history of community and territorial progress, told in the form of biographical sketches, and the steady demand for the editions of previous years has abundantly illustrated its interest and its value. Both as a record of enterprise and achievement, and as a compilation of chronological facts, “Nlen of Hawaii" has be -comea standard reference work in Hawaii and abroad. Copies are sent all over the world. Libraries in distant cities call for the succeeding editions. Locally, the book is constantly in use. This book is Volume IV of “lVlen of Hawaii.” The first edition was in l9l7, the second in l9Zl, the third in I925. To a certain degree the present edition supplements and com plements “Builders of Hawaii” U925), with which was incorporated that year’s edition of ‘‘Men of Hawaii.” For the broadest coverage of Hawaiian biographical record, "Builders of Hawaii" and this l930 edition of ‘‘Men of Hawaii" should be treated as one work, and so maintained in reference libraries. -

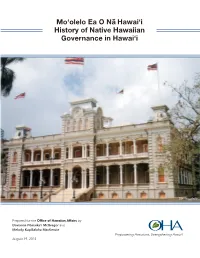

Mo'olelo Ea O Na¯ Hawai'i History of Native Hawaiian Governance In

Mo‘olelo Ea O Na¯ Hawai‘i History of Native Hawaiian Governance in Hawai‘i Courtesy photo Prepared for the Office of Hawaiian Affairs by Davianna Pōmaika‘i McGregor and Melody Kapilialoha MacKenzie Empowering Hawaiians, Strengthening Hawai‘i August 19, 2014 Authors Dr. Davianna Pōmaika‘i McGregor is a Professor and founding member of the Ethnic Studies Department at the University of Hawai‘i-Mānoa. Melody Kapilialoha MacKenzie is a Professor at the William S. Richardson School of Law, University of Hawaiʻi–Mānoa, and Director of Ka Huli Ao Center for Excellence in Native Hawaiian Law. Acknowledgements The authors would like to acknowledge the many people who have contributed to this work over the years including Richardson School of Law graduates Nāpali Souza, Adam P. Roversi, and Nicole Torres. We are particularly grateful for the comments and review of this manuscript by Lilikalā Kameʻeleihiwa, Senior Professor, Kamakakūokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies at the University of Hawaiʻi-Mānoa, whose depth of knowledge and expertise were invaluable in refining this moʻolelo. We are also thankful for the help of the staff of the OHA Advocacy Division who, under the direction of Kawika Riley, spent many hours proofreading and formatting this manuscript. Copyright © 2014 OFFICE OF HAWAIIAN AFFAIRS. All Rights Reserved. No part of this report may be reproduced or transmitted in whole or in part in any form without the express written permission of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, except that the United States Department of the Interior may reproduce or transmit this report as needed for the purpose of including the report in the public docket for Regulation Identifier Number 1090- AB05. -

Free Things to Do on Oahu

Free Things to Do on Oahu 1. ROYAL HAWAIIAN BAND Listen to the Royal Hawaiian Band at Iolani Palace on Fridays from 12:00 to 1:00pm. Concert calendar, please call (808) 922-5331 or visit http://www.rhb-music.com/?page_id=11. 2. ALOHA TOWER Relax harbor side at Aloha Tower Marketplace and listen to the island's most popular entertainers from the marketplace's waterfront stage as boats, barges and cruise ships float past. Upcoming events, please call (808) 566-2337 or visit http://www.alohatower.com/entertainment/calendar/. 3. MUSIC IN WAIKIKI Listen to Hawaii's best local entertainers performing in the hotels in Waikiki. 4. SUNSET ON THE BEACH Enjoy "Sunset on the Beach," as Kapahulu Pier is transformed into an outdoor movie theater, with live entertainment, food booths, and free Hollywood movies. For more information, please call (808) 923-1094 or visit http://www.sunsetonthebeach.net/. 5. INTERNATIONAL MARKETPLACE Take a stroll through International Marketplace, a bazaar of clothes, jewelry and souvenirs from the island's colorful merchants set under the shade of a large banyan tree. 6. ALA MOANA CENTER STAGE Stop by Ala Moana Center's Center stage, the hub for more than 500 performances annually, from keiki (children) hula to rock, from chorale music to street dancing. For more information, please call (808) 955-9517 or visit http://www.alamoanacenter.com/Events/Centertainment.aspx. 7. HONOLULU CITY LIGHTS Marvel at the "Honolulu City Lights" which illuminate the sky from the financial district to downtown celebrating the holidays in December and then stop in Honolulu Hale to enjoy the display of decorated Christmas trees.