Nostalgia and Hapa Haole Music in Early

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1Guitar PDF Songs Index

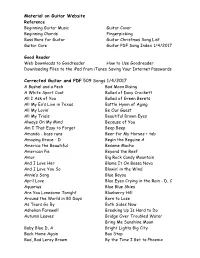

Material on Guitar Website Reference Beginning Guitar Music Guitar Cover Beginning Chords Fingerpicking Bass Runs for Guitar Guitar Christmas Song List Guitar Care Guitar PDF Song Index 1/4/2017 Good Reader Web Downloads to Goodreader How to Use Goodreader Downloading Files to the iPad from iTunes Saving Your Internet Passwords Corrected Guitar and PDF 509 Songs 1/4/2017 A Bushel and a Peck Bad Moon Rising A White Sport Coat Ballad of Davy Crockett All I Ask of You Ballad of Green Berets All My Ex’s Live in Texas Battle Hymn of Aging All My Lovin’ Be Our Guest All My Trials Beautiful Brown Eyes Always On My Mind Because of You Am I That Easy to Forget Beep Beep Amanda - bass runs Beer for My Horses + tab Amazing Grace - D Begin the Beguine A America the Beautiful Besame Mucho American Pie Beyond the Reef Amor Big Rock Candy Mountain And I Love Her Blame It On Bossa Nova And I Love You So Blowin’ in the Wind Annie’s Song Blue Bayou April Love Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain - D, C Aquarius Blue Blue Skies Are You Lonesome Tonight Blueberry Hill Around the World in 80 Days Born to Lose As Tears Go By Both Sides Now Ashokan Farewell Breaking Up Is Hard to Do Autumn Leaves Bridge Over Troubled Water Bring Me Sunshine Moon Baby Blue D, A Bright Lights Big City Back Home Again Bus Stop Bad, Bad Leroy Brown By the Time I Get to Phoenix Bye Bye Love Dream A Little Dream of Me Edelweiss Cab Driver Eight Days A Week Can’t Help Falling El Condor Pasa + tab Can’t Smile Without You Elvira D, C, A Careless Love Enjoy Yourself Charade Eres Tu Chinese Happy -

Download YAM011

yetanothermagazine filmtvmusic aug2010 lima film festival 2010 highlights blockbuster season from around the world in this yam we review // aftershocks, inception, toy story 3, the ghost writer, taeyang, se7en, boa, shinee, bibi zhou, jing chang, the derek trucks band, time of eve and more // yam exclusive interview with songwriter diane warren film We keep working on that, but there’s toy story 3 pg4 the ghost writer pg5 so much territory to cover, and so You know the address: aftershocks pg6 very little of us. This is why we need [email protected] inception pg7 lima film festival// yam contributors. We know our highlights pg9 readers are primarily located in the amywong // cover// US, but I’m hoping to get people yam exclusive from other countries to review their p.s.: I actually spoke to Diane interview with diane warren pg12 local releases. The more the merrier, Warren. She's like the soundtrack music people. of our lives, to anyone of my the derek trucks band - roadsongs pg16 generation anyway. Check it out. se7en - digital bounce pg16 shinee - lucifer pg17 Yup, we’re grovelling for taeyang - solar pg17 contributors. I’m particularly eminem - recovery pg18 macy gray - the sellout pg18 interested in someone who is jing chang - the opposite me pg18 located in New York, since we’ve bibi zhou - i.fish.light.mirror pg18 nick chou - first album pg19 received a couple of screening boa - hurricane venus pg19 invites, but we got no one there. tv Interested? Hit me up. bad guy pg20 time of eve pg20 books uso. -

09 1Bkrv.Donaghy.Pdf

book reviews 159 References Bickerton, Derek, and William H. Wilson. 1987. “Pidgin Hawaiian.” In Pidgin and Creole Lan- guages: Essays in Memory of John E. Reinecke, edited by Glenn G. Gilbert. Honolulu: Uni- versity of Hawai‘i Press. Drechsel, Emanuel J. 2014. Language Contact in the Early Colonial Pacific: Maritime Polynesian Pidgin before Pidgin English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Massam, Diane. 2000. “VSO and VOS: Aspects of Niuean Word Order.” In The Syntax of Verb Initial Languages, 97–117. Edited by Andrew Carnie and Eithne Guilfoyle. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Roberts, [S.] J. M. 1995. “Pidgin Hawaiian: A Sociohistorical Study.” Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages 10: 1–56. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. Romaine, Suzanne. 1988. Pidgin and Creole Languages. London: Longman. Hawaiian Music and Musicians (Ka Mele Hawai‘i A Me Ka Po‘e Mele): An Encyclopedic History, Second Edition. Edited by Dr. George S. Kanahele, revised and updated by John Berger. Honolulu: Mutual Publishing, 2012. xlix + 926 pp. Illus- trated. Appendix. Addendum. Index. $35.00 paper ‘Ōlelo Hō‘ulu‘ulu / Summary Ua puka maila ke pa‘i mua ‘ana o Hawaiian Music and Musicians ma ka MH 1979. ‘O ka hua ia o ka noi‘i lō‘ihi ma nā makahiki he nui na ke Kauka George S. Kanahele, ko The Hawaiian Music Foundation, a me nā kānaka ‘ē a‘e ho‘i he lehulehu. Ma ia puke nō i noelo piha mua ‘ia ai ka puolo Hawai‘i, me ka mana‘o, na ia puke nō e ho‘olako mai i ka nele o ka ‘ike pa‘a e pili ana i ka puolo Hawai‘i, kona mo‘olelo, kona mohala ‘ana a‘e, nā mea ho‘okani a pu‘ukani kaulana, a me nā kānaka kāko‘o pa‘a ma hope ona. -

Na Makua Mahalo Ia. Mormon Influences on Hawaiian Music and Dance

2 john kamealoha almeida called the dean of hawaiian composers for of hawaiian compositions although he Is pure portuguese na makua mahalo laia hormonmormon influences on hawaiian music and dance his thousands many of his songs are now classics probably the mostroostmoost popular being 6 sk 11 bt T lesu heme ke kanakakekanakaKe waiwai has been blind since the age of ten but was very helpful in raising money for the church through luaus and hula when the na makua mahalo laia awards were first envisioned it was intended shows throughout the 1930s and 1940s he is presently eightsixeight six years that their scope would remain limited to basically LDSLOS people who had disting- 190s old uished themselves in the performing arts for various reasons it has not been possible to retain this earlier restricted focus of the awards As a alice namakelua aunty is 90 years young and is remarkably spry and result even though recipients tend to be mainly drawn from LDSLOS ranks church active in her days she was a singer dancer translator composer membership is not the prime criterion for selection rather recipients are lecturer genealogist and slackstacksiacksiecksleckslackkeystackkeykey guitar artist she had a best- judged on the depth and quality of the contributions they have made to the selling album when she was eightytwoeighty two years old and still attends hawaiian cultural community an examination of the two sets of recipients church functions as best as she can she studledstudiedstudded hawaiian music for might better illustrate the criteria -

Pacific Islands Program

/ '", ... it PACIFIC ISLANDS PROGRAM ! University of Hawaii j Miscellaneous Work Papers 1974:1 . BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HAWAIIAN LANGUAGE MATERIALS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII, MANOA CAMPUS Second Printing, 1979 Photocopy, Summer 1986 ,i ~ Foreword Each year the Pacific Islands Program plans to duplicate inexpensively a few work papers whose contents appear to justify a wider distribution than that of classroom contact or intra-University circulation. For the most part, they will consist of student papers submitted in academic courses and which, in their respective ways, represent a contribution to existing knowledge of the Pacific. Their subjects will be as varied as is the multi-disciplinary interests of the Program and the wealth of cooperation received from the many Pacific-interested members of the University faculty and the cooperating com munity. Pacific Islands Program Room 5, George Hall Annex 8 University of Hawaii • PRELIMINARY / BIBLIOGRAPHY OF HAWAIIAN LANGUAGE MATERIALS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII, MANOA CAMPUS Compiled by Nancy Jane Morris Verna H. F. Young Kehau Kahapea Velda Yamanaka , . • Revised 1974 Second Printing, 1979 PREFACE The Hawaiian Collection of the University of Hawaii Library is perhaps the world's largest, numbering more than 50,000 volumes. As students of the Hawaiian language, we have a particular interest in the Hawaiian language texts in the Collection. Up to now, however, there has been no single master list or file through which to gain access to all the Hawaiian language materials. This is an attempt to provide such list. We culled the bibliographical information from the Hawaiian Collection Catalog and the Library she1flists. We attempted to gather together all available materials in the Hawaiian language, on all subjects, whether imprinted on paper or microfilm, on tape or phonodisc. -

A Concise Dictionary of Middle English

A Concise Dictionary of Middle English A. L. Mayhew and Walter W. Skeat A Concise Dictionary of Middle English Table of Contents A Concise Dictionary of Middle English...........................................................................................................1 A. L. Mayhew and Walter W. Skeat........................................................................................................1 PREFACE................................................................................................................................................3 NOTE ON THE PHONOLOGY OF MIDDLE−ENGLISH...................................................................5 ABBREVIATIONS (LANGUAGES),..................................................................................................11 A CONCISE DICTIONARY OF MIDDLE−ENGLISH....................................................................................12 A.............................................................................................................................................................12 B.............................................................................................................................................................48 C.............................................................................................................................................................82 D...........................................................................................................................................................122 -

The Making of a Short Film About George Helm

‘Apelila (April) 2020 | Vol. 37, No. 04 Hawaiian Soul The Making of a Short Film About George Helm Kolea Fukumitsu portrays George Helm in ‘Äina Paikai's new film, Hawaiian Soul. - Photo: Courtesy - - Ha‘awina ‘olelo ‘oiwi: Learn Hawaiian Ho‘olako ‘ia e Ha‘alilio Solomon - Kaha Ki‘i ‘ia e Dannii Yarbrough - When talking about actions in ‘o lelo Hawai‘i, think about if the action is complete, ongoing, or - reoccuring frequently. We will discuss how Verb Markers are used in ‘o lelo hawai‘i to illustrate the completeness of actions. E (verb) ana - actions that are incomplete and not occurring now Ke (verb) nei - actions that are incomplete and occurring now no verb markers - actions that are habitual and recurring Ua (verb) - actions that are complete and no longer occurring Use the information above to decide which verb markers are appropriate to complete each pepeke painu (verb sentence) below. Depending on which verb marker you use, both blanks, one blanks, or neither blank will be filled. - - - - - - - - - I ka la i nehinei I keia manawa ‘a no I ka la ‘apo po I na la a pau Yesterday At this moment Tomorrow Everyday - - - - - - - I ka la i nehinei, I kEia manawa ‘a no, I ka la ‘apo po, lele - - I na la a pau, inu ‘ai ka ‘amakihi i ka mele ka ‘amakihi i ka ka ‘amakihi i ke ka ‘amakihi i ka wai. mai‘a. nahele. awakea. - E ho‘i hou mai i ke-ia mahina a‘e! Be sure to visit us again next month for a new ha‘awina ‘o-lelo Hawai‘i (Hawaiian language lesson)! Follow us: /kawaiolanews | /kawaiolanews | Fan us: /kawaiolanews ‘O¯LELO A KA POUHANA ‘apelila2020 3 MESSAGE FROM THE CEO WE ARE STORYTELLERS mo‘olelo n. -

Jeremy Sassoon – Solo Playlist

JEREMY SASSOON – SOLO PLAYLIST Jazz/Swing Ain't misbehavin' Aint that a kick in the head All of me All the way Almost like being in love A nightingale sang in Berkeley square As time goes by At last Autumn leaves Beyond the sea Body and soul Bye bye blackbird Cheek to Cheek Come fly with me Corcovado Cry me a river Don’t get around much anymore Everytime we say goodbye Feeling good Fever Fly me to the moon Foggy day Georgia on my mind Girl from Ipanema God bless the child Have you met Miss Jones I can't give you anything but love I get a kick out of you I left my heart in San Francisco I only have eyes for you Is you is or is you ain’t my baby It don't mean a thing It had to be you It’s alright with me It’s only a paper moon I’ve got you under my skin I wish I knew how it would feel to be free (Film 2011) Let’s call the whole thing off Let’s do it, let’s fall in love Let’s face the music and dance Let’s fall in love Let there be love Love me or leave me Lullaby of birdland Mack the knife Makin whoopee Misty Moonglow Moon river Mr Bojangles My baby just cares for me My favourite things My funny valentine My romance My way Night and day One note samba On the sunny side of the street Orange coloured sky Our love is here to stay Over the rainbow Satin doll Shadow of your smile Smile So danco samba Summertime Sway Take the A train Tenderly The lady is a tramp The look of love The nearness of you The way you look tonight They can’t take that away from me Unforgettable When I fall in love You make me feel so young Piano Bar/Pop/Easy Listening -

Irene Haar, 86, of Honolulu, a Retired Restaurateur, Kamehameha Schools Dining Hall Manager, and Ceramic Artist, Died Wednesday Sep 1, 1999

H Irene Haar, 86, of Honolulu, a retired restaurateur, Kamehameha Schools dining hall manager, and ceramic artist, died Wednesday Sep 1, 1999. She was born in Vac, Hungary. She is survived by sons Tom and Andrew; daughter Vera, three grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. Private services. Mariano Habon Haber, 71, of Waianae, died Feb. 4, 1999 at St. Francis Medical Center West. He was born in the Philippines. He is survived by wife Felipa; sons Ricardo, Rolando, Wilfredo and Fernando; daughters Elizabeth, Milagros and Violeta; sisters Leonarda, Rufina and Perpetua, and 18 grandchildren. Services: 7 p.m. Wednesday at Nuuanu Mortuary. Call: 6 to 9 p.m. Casual attire. No flowers. Burial in the Philippines. KO HADAMA, 86, of Honolulu, died Oct. 29, 1999. Born in Koloa, Kauai. Retired as a painting foreman. Survived by wife, Yuriko; son, Alan. Private service held. Arrangements by Nuuanu Mortuary. Sheri Hadgi,43, of Honolulu died last Thursday Feb 4, 1999 in Honolulu. She was born in Clark Las Vegas, Nev. She is survived by fiance George H. Wong and sisters Kate Mead and Ann Davis. Services: 10:30 a.m. tomorrow at Castle Hospital auditorium. Casual attire. Stanley F. Haedrich Jr.,75, of Detroit Lakes, Minn., formerly of Honolulu, a retired chief estimator for Hawaiian Dredging, died Jan. 10, 1999 in Fargo, N.D. He was born in Minneapolis. He is survived by wife Marilyn and longtime friend Dorothy Brockhausen. Services on the mainland. Emma A.P. Haena, 94, of Hilo, died Saturday Aug 21, 1999 at home. Born in Waimea, she is survived by daughters Jane Kakelaka, Minerva Naehu, Emmeline Santiago Foster, Blossom Kelii and Lydia Haena; son Thomas Nahiwa; grandchildren; great- grandchildren; and great-great-grandchildren. -

2020 C'nergy Band Song List

Song List Song Title Artist 1999 Prince 6:A.M. J Balvin 24k Magic Bruno Mars 70's Medley/ I Will Survive Gloria 70's Medley/Bad Girls Donna Summers 70's Medley/Celebration Kool And The Gang 70's Medley/Give It To Me Baby Rick James A A Song For You Michael Bublé A Thousands Years Christina Perri Ft Steve Kazee Adventures Of Lifetime Coldplay Ain't It Fun Paramore Ain't No Mountain High Enough Michael McDonald (Version) Ain't Nobody Chaka Khan Ain't Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Of Me John Legend American Boy Estelle and Kanye Applause Lady Gaga Ascension Maxwell At Last Ella Fitzgerald Attention Charlie Puth B Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Best Part Daniel Caesar (Feat. H.E.R) Bettet Together Jack Johnson Beyond Leon Bridges Black Or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Boogie Oogie Oogie Taste Of Honey Break Free Ariana Grande Brick House The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morisson Butterfly Kisses Bob Carisle C Cake By The Ocean DNCE California Gurl Katie Perry Call Me Maybe Carly Rae Jespen Can't Feel My Face The Weekend Can't Help Falling In Love Haley Reinhart Version Can't Hold Us (ft. Ray Dalton) Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Can't Stop The Feeling Justin Timberlake Can't Get Enough of You Love Babe Barry White Coming Home Leon Bridges Con Calma Daddy Yankee Closer (feat. Halsey) The Chainsmokers Chicken Fried Zac Brown Band Cool Kids Echosmith Could You Be Loved Bob Marley Counting Stars One Republic Country Girl Shake It For Me Girl Luke Bryan Crazy in Love Beyoncé Crazy Love Van Morisson D Daddy's Angel T Carter Music Dancing In The Street Martha Reeves And The Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Danza Kuduro Don Omar Dark Horse Katy Perry Despasito Luis Fonsi Feat. -

Musical! Theatre!

Premier Sponsors: Sound Designer Video Producer Costume Coordinator Lance Perl Chrissy Guest Megan Rutherford Production Stage Manager Assistant Stage Manager Stage Management Apprentice Mackenzie Trowbridge* Kat Taylor Lyndsey Connolly Production Manager Dramaturg Assistant Director Adam Zonder Hollyann Bucci Jacob Ettkin Musical Director Daniel M. Lincoln Directors Gerry McIntyre+ & Michael Barakiva+ We wish to express our gratitude to the Performers’ Unions: ACTORS’ EQUITY ASSOCIATION AMERICAN GUILD OF MUSICAL ARTISTS AMERICAN GUILD OF VARIETY ARTISTS SAG-AFTRA through Theatre Authority, Inc. for their cooperation in permitting the Artists to appear on this program. * Member of the Actor's Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. + ALEXA CEPEDA is delighted to be back at The KRIS COLEMAN* is thrilled to return to the Hangar. Hangar! Select credits: Mamma Mia (CFRT), A Broadway Credit: Jersey Boys (Barry Belson) Chorus Line (RTP), In The Heights (The Hangar Regional Credit: Passing Strange (Narrator), Jersey Theatre), The Fantasticks (Skinner Boys - Las Vegas (Barry Belson), Chicago (Hangar Barn), Cabaret (The Long Center), Anna in the Theatre, Billy Flynn), Dreamgirls (Jimmy Early), Sister Tropics (Richard M Clark Theatre). She is the Act (TJ), Once on This Island (Agwe), A Midsummer founder & host of Broadway Treats, an annual Nights Dream (Oberon) and Big River (Jim). benefit concert organized to raise funds for Television and film credits include: The Big House Animal Lighthouse Rescue (coming up! 9/20/20), and is (ABC), Dumbbomb Affair, and The Clone. "As we find ourselves currently working on her two-person musical Room 123. working through a global pandemic and race for equality, work Proud Ithaca College BFA alum! "Gracias a mamacita y papi." like this shows the value and appreciation for all. -

The Pleasures and Rewards of Hawaiian Music for an 'Outsider'

12 Living in Hawai‘i: The Pleasures and Rewards of Hawaiian Music for an ‘Outsider’ Ethnomusicologist Ricardo D . Trimillos Foreword I first met Stephen Wild at the 1976 Society for Ethnomusicology meeting in Philadelphia. Since that time we have enjoyed four decades as session- hopping colleagues and pub-crawling mates. In regard to the former, most memorable was the 1987 International Council for Traditional Music meeting in Berlin, where, appropriate to our honoree, one of the conference themes was ‘Ethnomusicology at Home’. It is this aspect of Stephen’s service that I celebrate in my modest effort for this festschrift. In 2006, the journal Ethnomusicology produced its ‘50th Anniversary Commemorative Issue’, which contained the essay ‘Ethnomusicology Down Under: A Distinctive Voice in the Antipodes?’ (Wild 2006). It was an informative and at times prescriptive account of the trajectory for ethnomusicology in Australia. I found the essay a most engaging exercise in personal positioning by an author within a historical narrative, one in which personality and persona were very much in evidence. Inspired by the spirit of that essay and emboldened by its novel approach, I share 335 A DISTINCTIVE VOICE IN ThE ANTIPODES observations about ‘doing ethnomusicology’ where I live—in Honolulu, Hawai‘i. This brief and personal account deliberately draws parallels with our honoree’s experiences and activities during a long career in his ‘homeplace’ (Cuba and Hummon 1993). The pleasures of Hawaiian music in California My first encounters with Hawaiian music were not in Hawai‘i but in San Jose,1 California, locale for the first two decades of my life.