Opera and Operetta in Nineteenth-Century Hawai'i

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AMERICA's ANNEXATION of HAWAII by BECKY L. BRUCE

A LUSCIOUS FRUIT: AMERICA’S ANNEXATION OF HAWAII by BECKY L. BRUCE HOWARD JONES, COMMITTEE CHAIR JOSEPH A. FRY KARI FREDERICKSON LISA LIDQUIST-DORR STEVEN BUNKER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2012 Copyright Becky L. Bruce 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This dissertation argues that the annexation of Hawaii was not the result of an aggressive move by the United States to gain coaling stations or foreign markets, nor was it a means of preempting other foreign nations from acquiring the island or mending a psychic wound in the United States. Rather, the acquisition was the result of a seventy-year relationship brokered by Americans living on the islands and entered into by two nations attempting to find their place in the international system. Foreign policy decisions by both nations led to an increasingly dependent relationship linking Hawaii’s stability to the U.S. economy and the United States’ world power status to its access to Hawaiian ports. Analysis of this seventy-year relationship changed over time as the two nations evolved within the world system. In an attempt to maintain independence, the Hawaiian monarchy had introduced a westernized political and economic system to the islands to gain international recognition as a nation-state. This new system created a highly partisan atmosphere between natives and foreign residents who overthrew the monarchy to preserve their personal status against a rising native political challenge. These men then applied for annexation to the United States, forcing Washington to confront the final obstacle in its rise to first-tier status: its own reluctance to assume the burdens and responsibilities of an imperial policy abroad. -

The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson Walter Murray Gibson the Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson HAWAII’S MINISTER of EVERYTHING

The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson Walter Murray Gibson The Fantastic Life of Walter Murray Gibson HAWAII’S MINISTER OF EVERYTHING JACOB ADLER and ROBERT M. KAMINS Open Access edition funded by the National En- dowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Licensed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Inter- national (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits readers to freely download and share the work in print or electronic format for non- commercial purposes, so long as credit is given to the author. Derivative works and commercial uses require permission from the publisher. For details, see https://creativecommons.org/li- censes/by-nc-nd/4.0/. The Creative Commons license described above does not apply to any material that is separately copy- righted. Open Access ISBNs: 9780824883669 (PDF) 9780824883676 (EPUB) This version created: 5 September, 2019 Please visit www.hawaiiopen.org for more Open Access works from University of Hawai‘i Press. © 1986 UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED For Thelma C. Adler and Shirley R. Kamins In Phaethon’s Chariot … HAETHON, mortal child of the Sun God, was not believed by his Pcompanions when he boasted of his supernal origin. He en- treated Helios to acknowledge him by allowing him to drive the fiery chariot of the Sun across the sky. Against his better judg- ment, the father was persuaded. The boy proudly mounted the solar car, grasped the reins, and set the mighty horses leaping up into the eastern heavens. For a few ecstatic moments Phaethon was the Lord of the Sky. -

The Minstrel and the Swan

The MinstrelCover - picture of Wallace and per- and thehaps Swan Hayes. Titlev Australia commemorates two great Irish artistes: William Vincent Wallace — 1812-1865 & Catherine Hayes — 1818-1861 William Vincent Wallace by Francois Davignon. Lithograph by Endicott. Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland. Jennifer Schatzle — Soprano Meryl Wilkinson — Harpist and Singer Jennifer is a graduate of the University of Melbourne, and holds a Diploma in Opera Bendigo based harpist and singer Meryl Wilkinson has made a speciality of music Performance of the Victorian college of the Arts Opera Studio. Her major roles have and songs of the Celtic countries. She has attended harp summer schools in Scotland included Pamina in “The Magic Flute,” Susanna in “the Marriage of Figaro,” and and Ireland, and she has produced two CDs featuring the music and songs of these Lauretta in “Gianni Schicchi.” Jennifer has represented sopranos Catherine Hayes, countries (Harp of my Heart and A Potpourri of Harp and Song). Meryl has performed Amy Castles, and Amy Sherwin in their commemorative concerts. She also sang at the National Celtic Festival in Portarlington, the Kilmore Celtic Festival, and the the role of Maritana in the Wallace bicentenary concerts’ excerpts from “Maritana” Maldon Folk Festival. She sings in the Celtic languages of Irish and Scottish Gaelic. presented by John Clancy in Bendigo and Melbourne in 2012. Carolyn Vaughan — Soprano Peter Hunt — Baritone Carolyn Vaughan won the Sydney Sun Aria a number of years ago. Her operatic Having worked initially in theatre, short film, television, and cabaret, Peter began career then took her to England, where she sang for some years with the studying classical singing at the Conservatorium of Music in Sydney. -

Opernaufführungen in Stuttgart

Opernaufführungen in Stuttgart ORIGINALTITEL AUFFÜHRUNGSTITEL GATTUNG LIBRETTIST KOMPONIST AUFFÜHRUNGSDATEN (G=Gastspiel)(L=Ludwigsburg)(C=Cannstatt) Euryanthe Euryanthe Oper Helemine von Chezy C(arl M(aria) von 1833: 13.03. ; 28.04. - 1863: 01.02. - 1864: 17.01. - Weber 1881; 12.02. (Ouverture) - 1887: 20.06 (Ouverture) - 1890: 16.02. ; 26.03. ; 25.09. ; 02.11. - 1893: 07.06 - Abu Hassan Oper in 1 Akt Franz Karl Hiemer Carl Maria von Weber 1811: 10.07. - 1824: 08.12. - 1825: 07.01. Achille Achilles Große heroische Nach dem Ferdinand Paer 1803: 30.09. ; 03.10. ; 31.10. ; 18.11. - 1804: Oper in 3 Akten Italienischen des 23.03. ; 18.11. - 1805: 17.06. ; 03.11. ; 01.12. - Giovanni DeGamerra 1806: 18.05. - 1807: 14.06. ; 01.12. - 1808: 18.09. - von Franz Anton 1809: 08.09. - 1810: 01.04. ; 29.07. - 1812: 09.02. ; Maurer 01.11. - 1813: 31.10. - 1816: 11.02. ; 09.06. - 1817: 01.06. - 1818: 01.03. - 1820: 15.01. - 1823: 17.12. - 1826: 08.02. Adelaide di Adelheit von Guesclin Große heroische Aus dem Italienischen Simon Mayr 1805: 21.07. ; 02.08. ; 22.09. - 1806: 02.03. ; 14. 09. Guescelino Oper in 2 Akten ; 16.09. (L). - 1807: 22.02. ; 30.08.(L) ; 06.09. - 1809: 07.04. - 1810: 11.04. - 1814: 28.08.(L) ; 09.10. - 1816: 05.05. ; 18.08. Adelina (auch Adeline Oper in 1 Akt Nach dem Pietro Generali 1818: 23.03. Luigina, Luisina) Italienischen von Franz Karl Hiemer - Des Adlers Horst Romantisch- Carl von Holtei Franz Gläser 1852: 30.04. ; 02.05. -

Ms Coll\Wheeler, R. Wheeler, Roger, Collector. Theatrical

Ms Coll\Wheeler, R. Wheeler, Roger, collector. Theatrical memorabilia, 1770-1940. 15 linear ft. (ca. 12,800 items in 32 boxes). Biography: Proprietor of Rare Old Programs, Newtonville, Mass. Summary: Theatrical memorabilia such as programs, playbills, photographs, engravings, and prints. Although there are some playbills as early as 1770, most of the material is from the 19th and 20th centuries. In addition to plays there is some material relating to concerts, operettas, musical comedies, musical revues, and movies. The majority of the collection centers around Shakespeare. Included with an unbound copy of each play (The Edinburgh Shakespeare Folio Edition) there are portraits, engravings, and photographs of actors in their roles; playbills; programs; cast lists; other types of illustrative material; reviews of various productions; and other printed material. Such well known names as George Arliss, Sarah Bernhardt, the Booths, John Drew, the Barrymores, and William Gillette are included in this collection. Organization: Arranged. Finding aids: Contents list, 19p. Restrictions on use: Collection is shelved offsite and requires 48 hours for access. Available for faculty, students, and researchers engaged in scholarly or publication projects. Permission to publish materials must be obtained in writing from the Librarian for Rare Books and Manuscripts. 1. Arliss, George, 1868-1946. 2. Bernhardt, Sarah, 1844-1923. 3. Booth, Edwin, 1833-1893. 4. Booth, John Wilkes, 1838-1865. 5. Booth, Junius Brutus, 1796-1852. 6. Drew, John, 1827-1862. 7. Drew, John, 1853-1927. 8. Barrymore, Lionel, 1878-1954. 9. Barrymore, Ethel, 1879-1959. 10. Barrymore, Georgiana Drew, 1856- 1893. 11. Barrymore, John, 1882-1942. 12. Barrymore, Maurice, 1848-1904. -

This City of Ours

THIS CITY OF OURS By J. WILLIS SAYRE For the illustrations used in this book the author expresses grateful acknowledgment to Mrs. Vivian M. Carkeek, Charles A. Thorndike and R. M. Kinnear. Copyright, 1936 by J. W. SAYRE rot &?+ *$$&&*? *• I^JJMJWW' 1 - *- \£*- ; * M: . * *>. f* j*^* */ ^ *** - • CHIEF SEATTLE Leader of his people both in peace and war, always a friend to the whites; as an orator, the Daniel Webster of his race. Note this excerpt, seldom surpassed in beauty of thought and diction, from his address to Governor Stevens: Why should I mourn at the untimely fate of my people? Tribe follows tribe, and nation follows nation, like the waves of the sea. It is the order of nature and regret is useless. Your time of decay may be distant — but it will surely come, for even the White Man whose God walked and talked with him as friend with friend cannot be exempt from the common destiny. We may be brothers after all. Let the White Man be just and deal kindly with my people, for the dead are not powerless. Dead — I say? There is no death. Only a change of worlds. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE 1. BELIEVE IT OR NOT! 1 2. THE ROMANCE OF THE WATERFRONT . 5 3. HOW OUR RAILROADS GREW 11 4. FROM HORSE CARS TO MOTOR BUSES . 16 5. HOW SEATTLE USED TO SEE—AND KEEP WARM 21 6. INDOOR ENTERTAINMENTS 26 7. PLAYING FOOTBALL IN PIONEER PLACE . 29 8. STRANGE "IFS" IN SEATTLE'S HISTORY . 34 9. HISTORICAL POINTS IN FIRST AVENUE . 41 10. -

Mormon Beginnings in Samoa: Kimo Pelio, Samuela Manoa and Walter

MORMON BEGINNINGS IN SAMOA: KIMO BELIO, SAMUELA MANOA AND WALTER MURRAY GIBSON by Spencer McBride Imprisoned in a Dutch prison in Malaysia, the young American adventurer Walter Murray Gibson claimed to have received a profound revelation. He writes, “While I lay in a dungeon in the island of Java, a voice said to me, ‘You shall show the way to a people, who shall build up a kingdom in these isles, whose lines of power shall run around the earth.’ My purposes of life were changed from that hour.”1 This, he felt, was confirmation of his previously imbedded ideas that he was indeed destined to create and lead an empire in the islands of the Pacific Ocean. When Gibson’s path crossed those of Kimo Belio, Samuela Manoa and the Mormon Church in Hawaii and Samoa, the results of his imperial mindset would have a significant effect. The arrival of the first “Mormon” missionaries in Samoa, and their 25 year stay in those islands without correspondence or assistance from the church’s headquarters, is a fascinating account worthy of being related in the most complete form possible. The calling of two native Hawaiians to serve such a mission helps to uncover the motivations of the politically ambitious man who had entwined his aspirations for empire with the building up of the Mormon Church. The unauthorized dispatch of Kimo Belio a Manoa to Samoa by Walter Murray Gibson was an attempt to further his own political aspirations by spreading the Mormon faith in the Pacific. However, the resulting missionary service of Belio and Manoa failed to grant Gibson greater political influence, but did successfully lay the foundation of a lasting Mormon presence in Samoa. -

L'opérette Est-Elle Amenée À Disparaître ? Christiane Dupuy

L'opérette est-elle amenée à disparaître ? Christiane Dupuy-Stutzmann Un grand historien de la danse à dit : « la France a ceci de particulier, qu’elle possède une terre féconde, une terre qui crée beaucoup de choses dans tous les domaines, mais qui contrairement aux autres, oublie son passé ». Ce triste constat est également valable pour ce spectacle total qu’est l’opérette, dont l’influence universelle, née sur les bords de la Seine, a donné lieu à un répertoire immense. Le metteur en scène argentin Jérôme Savary décédé en 2013, disait à ce propos, « la France est un pays bizarre qui condamne son opérette en ne la faisant plus représenter alors que lorsqu’on me demande de mettre en scène au Théâtre du Châtelet ou au Théâtre des Champs-Elysées « La Vie Parisienne » ou « La Périchole», la billetterie est littéralement prise d’assaut par le public parisien dès le 1er jour d’ouverture de la location ! » Comme on peut le constater, le goût du public n’est nullement en cause ! Les amateurs d’opérette, certes plus nombreux parmi les séniors, réclament inlassablement le retour d’une programmation même restreinte ! L’argument de ses détracteurs consiste à faire passer l’opérette pour un genre dépassé qui ne serait plus du goût des jeunes générations alors qu’en réalité, c’est plutôt par ignorance de ce répertoire et parce qu’on ne le programme plus que les jeunes ne s’y intéressent plus ! Il est avéré que l’opérette n’est pratiquement plus programmée dans les saisons lyriques de nos théâtres français. -

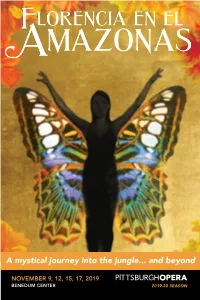

A Mystical Journey Into the Jungle... and Beyond

A mystical journey into the jungle... and beyond NOVEMBER 9, 12, 15, 17, 2019 BENEDUM CENTER 2019-20 SEASON SINCE 1893 WHEN OUR CUSTOMERS FACED THE UNEXPECTED WE WERE THERE For over 125 years Henderson Brothers has gone to heroic lengths to provide our customers with peace of mind. Because you can’t expect what tomorrow may bring. That’s why you have us. Commercial Insurance | Personal Insurance | Employee Benefits hendersonbrothers.com LETTER FROM OUR BOARD LEADERSHIP LETTER FROM OUR GENERAL DIRECTOR DEAR FRIENDS, DEAR FRIENDS, Welcome to Pittsburgh Opera’s production of Florencia I am delighted to welcome you to Florencia en en el Amazonas. We are happy to be able to join you in el Amazonas, the first Spanish-language opera in this mystical, magical journey down the Amazon. Pittsburgh Opera’s 81-year history. Like a proud parent, I can’t restrain myself from Our production of this contemporary opera by boasting about this fantastic cast. After a stunning role Mexican composer Daniel Catán illustrates the rich debut as Princess Turandot with us in 2017, our very diversity of the operatic tradition and Pittsburgh own Alexandra Loutsion returns to the Benedum today Opera’s commitment to it. For the first time, Pittsburgh in the title role of diva Florencia Grimaldi. Those of you © Daniel V. Klein Photography © Daniel V. audiences will enjoy an opera in Spanish with a libretto who were here last month for Don Giovanni will no based upon literature in the Latin American genre of doubt recognize Craig Verm (who sang the role of Don Giovanni) as deck-hand/ Magical Realism. -

The Magic Flute

OCTOBER 09, 2015 THE FRIDAY | 8:00 PM OCTOBER 11, 2015 MAGIC SUNDAY | 4:00 PM OCTOBER 13, 2015 FLUTE TUESDAY | 7:00 PM FLÂNEUR FOREVER Honolulu Ala Moana Center (808) 947-3789 Royal Hawaiian Center (808) 922-5780 Hermes.com AND WELCOME TO AN EXCITING NEW SEASON OF OPERAS FROM HAWAII OPERA THEATRE. We are thrilled to be opening our 2014) conducts, and Allison Grant As always we are grateful to you, season with one of Mozart’s best- (The Merry Widow, 2004) directs this our audience, for attending our loved operas: The Magic Flute. This new translation of The Magic Flute by performances and for the support colorful production comes to us Jeremy Sams. you give us in so many ways from Arizona Opera, where it was throughout the year. Without your created by Metropolitan Opera This will be another unforgettable help we simply could not continue stage director, Daniel Rigazzi. season for HOT with three to bring the world’s best opera to Inspired by the work of the French sensational operas, including Hawaii each year. surrealist painter, René Magritte, a stunning new production of the production is fi lled with portals– Benjamin Britten’s A Midsummer But now sit back and enjoy Mozart’s doorways and picture frames–that Night’s Dream, directed by Henry The Magic Flute. lead the viewer from reality to Akina, with videography by Adam dreams. With a cast that includes Larsen (Siren Song, 2015) and a MAHALO Antonio Figueroa as Tamino and So spectacular production of Verdi’s Il Young Park as the formidable Queen Trovatore designed by Peter Dean Henry G. -

'Āinahau: the Genealogy of Ka'iulani's Banyan

ralph thomas kam The Legacy of ‘Āinahau: The Genealogy of Ka‘iulani’s Banyan “And I, in her dear banyan shade, Look vainly for my little maid.” —Robert Louis Stevenson ‘Āinahau, the home of Archibald Scott Cleghorn, his wife, Princess Miriam Kapili Likelike and their daughter, Princess Victoria Ka‘iu- lani, no longer stands, the victim of the transformation of Waikīkī from the playground of royalty to a place of package tours, but one storied piece of its history continues to literally spread its roots through time in the form of the ‘Āinahau banyan. The ‘Āinahau ban- yan has inspired poets, generated controversy and influenced leg- islation. Hundreds of individuals have rallied to help preserve the ‘Āinahau banyan and its numerous descendants. It is fitting that Archibald Cleghorn (15 November 1835–1 Novem- ber 1910), brought the banyan to Hawai‘i, for the businessman con- tinued the legacy of the traders from whom the banyan derives it etymology. The word banyan comes from the Sanskrit “vaniyo” and originally applied to a particular tree of this species near which the traders had built a booth. The botanical name for the East Indian fig tree, ficus benghalensis, refers to the northeast Indian province of Ralph Kam holds an M.A. and a Ph.D. in American Sudies from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and an M.A. in Public Relations from the University of Southern California. The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 45 (2011) 49 50 the hawaiian journal of history Bengal, now split between India and Bangladesh. That the tree was introduced in Hawai‘i after Western contact is reflected in its Hawai- ian name: “paniana,” a transliteration of the English word. -

To See the Full #Wemakeevents Participation List

#WeMakeEvents #RedAlertRESTART #ExtendPUA TOTAL PARTICIPANTS - 1,872 and counting Participation List Name City State jkl; Big Friendly Productions Birmingham Alabama Design Prodcutions Birmingham Alabama Dossman FX Birmingham Alabama JAMM Entertainment Services Birmingham Alabama MoB Productions Birmingham Alabama MV Entertainment Birmingham Alabama IATSE Local78 Birmingham Alabama Alabama Theatre Birmingham Alabama Alys Stephens Performing Arts Center (Alabama Symphony) Birmingham Alabama Avondale Birmingham Alabama Iron City Birmingham Alabama Lyric Theatre - Birmingham Birmingham Alabama Saturn Birmingham Alabama The Nick Birmingham Alabama Work Play Birmingham Alabama American Legion Post 199 Fairhope Alabama South Baldwin Community Theatre Gulf Shores Alabama AC Marriot Huntsville Alabama Embassy Suites Huntsville Alabama Huntsville Art Museum Huntsville Alabama Mark C. Smith Concert Hall Huntsville Alabama Mars Music Hall Huntsville Alabama Propst Arena Huntsville Alabama The Camp Huntsville Alabama Gulfquest Maritime Museum Mobile Alabama The Steeple on St. Francis Mobile Alabama Alabama Contempory Art Center Mobile Alabama Alabama Music Box Mobile Alabama The Merry Window Mobile Alabama The Soul Kitchen Music Hall Mobile Alabama Axis Sound and Lights Muscle Shoals Alabama Fame Recording Studio Muscle Shoals Alabama Sweettree Productions Warehouse Muscle Shoals Alabama Edwards Residence Muscle Shoals Alabama Shoals Theatre Muscle Shoals Alabama Mainstreet at The Wharf Orange Beach Alabama Nick Pratt Boathouse Orange Beach Alabama