Production Offshoring and the Skill Composition of Italian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Active Filers - Metropolitan Transportation Authority 10/28/2020

Active Filers - Metropolitan Transportation Authority 10/28/2020 Name Yrs in Role Aarons, Marcel 5.42 Abayeva, Bela 5.1 Abbas, Syed 3.17 Abdallah, Ahmad 2.38 Abdallah, Thomas 8.39 Abdelkader, Ashraf 0.43 Abdelrahman, Aliaa 6.79 Abili, John 9.48 Aboagye, Nana 3.18 Abraham, George 4.64 Abraham, Sajan 9.94 Abraham-David, Ruby 1.16 Abramchayeva, Liliya 2.09 Acampora, Christopher 3.04 Accardo, Matthew 2.5 Accettura, Stephen 1.69 Accousti, James 2.07 Acerra, Paul 8.41 Acevedo, Kenneth 8.39 Acevedo, Victor 1.08 Acevedo, Wilma 2.87 Ackerman, Neil 5.21 Acosta, Leudy 0.07 Acosta, Raul 3.04 Adam, Mohamed 2.11 Adams, Benjamin 2.15 Adams, Chantay 2.23 Adams, Diane 3.84 Adams, Eric 1.58 Adams, Gerald 3.6 Adams, Julie 3.39 Addoquaye, Anna 10.88 Adeleke, Juliet 6.29 Adeleye, Ireoluwa 0.93 Adetchessi, Raoufou 0.98 Adewolu, Olasupo 3.4 Adinolfi, Nina 3.33 Adlam, Christopher 0.96 Adomah, Chereh 8.39 Aebly, Richard 5.88 Afify, Ebtesam 5.14 Afko, Koffi 4.31 Agard, Aldale 4.75 Aglitsky, Yekaterina 5.99 Agosto, Casildo 1.25 Agrawal, Sonika 2.35 Agrelo, Joshua 2.83 Agyei, Anita 6.04 Ahamed, Ali 3.76 Ahearn, Mary 3.45 Ahmed, Azad 2.42 Ahmed, Ekhlas 9.91 Ahmed, Humayun 7.19 Ahmed, Khondker 6.04 Ahmed, Margaret 4.09 Ahmed, Shahzad 1.38 Aiello, Alexandra 2.03 Aiello, Gavin 5.11 Aievoli, Steven 6.16 Aiyer, Lata 0.79 Akbar, Reinhard 4.37 Akeredolu, Elias 5.31 Akpinar, Ali 4.09 Akselrod, Leonard 2.63 Alagna, Joseph 8.04 Albano, Albert 2.26 Albano, Steven 9.91 Albert, Alyson 2.11 Albert, Andrew 1.36 Albino, Jesus 3.32 Albino, Wayne 7.97 Alcantara, Minosca 5.55 Alcide, -

Data Report for Fiscal Year 2020 (Highly Compensated Report)

MTA - Data Report for Fiscal Year 2020 (Highly Compensated Report) *Last Name *First Name Middle *Title *Group School Name Highest Degree Prior Work Experience Initial O'Brien James J Mgr. Maint. Contract Admin. Managerial UNKNOWN UNKNOWN MTA Agency Berani Alban Supervising Engr Electrical Managerial CUNY City College Master of Engineering Self Employed Moravec Eva M Assistant General Counsel Professional Pace University White Plains Juris Doctor Dept. of Finance OATH Angel Nichola O AVPCenBusDisTolUnit Managerial NYU Stern School of Business Master of Mechanical Engi MTA Agency Khuu Howard N Assistant Controller Managerial Baruch College Master of Business Admin Home Box Office Reis Sergio Director Ops. Tolls & Fac. Sys Managerial Long Island University Bachelor of Science Tag Americas LLC Jacobs Daniel M Sr Dir Plan Inno&Pol Ana Managerial Rutgers University Master of Engineering MTA Agency Wilkins Alphonso Senior Safety Engineer Professional High School Diploma EnviroMed Services Inc. Walker Kellie Labor Counsel Professional Boston University Law Juris Doctor NYC Department of Education Mondal Mohammad S Supervising Engineer Structure Managerial Foreign - Non US College/Unive Bachelor Civil Engineerin Department of Buildings Friman Paul Exec Asst General Counsel Professional New York University Juris Doctor NYS Supreme Court NY Prasad Indira G Sr Project Manager TSMS Professional Stevens Institute of Technolog Master of Science Mitsui O.S.K. NY Li Bin Supervising Engineer Structure Managerial Florida International Univ Doctor of Philosophy -

Gazzetta Ufficiale Del Regno D'italia N. 121 Del 21 Maggio 1874 Parte

.A.nno 187'4. Bosna - Gio eat, SL191aggio Wurn. 121. ASSOCIAZIONI INSERZIONI GA GRTTA UFFICIALE Esteso, anmente y di cavono alla Tipografia Eredi Betts: Un numero separato in Roma, een- In Ëema, via dei Lucchesi, n. 4; tesimi 10, per tutto il Begne cente- ab 1 In Terino, viadellaCorted Appello, a m e P vincie del Regno ed ati'E• stero agli Utici postall. mestri anticipati, è aumentato dalle 150 alle innei Fabrisin, id. di Castelgrande; sione scritta e sottoscritta di loro pugno su carts be PARTE UFFICIALE 200 lire. Nennella Aniello,id. di Casamicciola; lata da eentesimi 50, ed unirvi i seguenti documenti: id. I volontari l'esame d'idoneith a retribuito: 11 munito Id. Garganico Carid, M. 18. (Treno) ; Mastrojecovo Erneste, id, di Trivento; per poeto Ordiniamo che presente decreto, Il decreto di nomina a volontario Id. Fahdsi Nicola, id.id. id.•, Palmera id. di Petrella a) demaniale; del deBo Stak sia inserto nella Rae- Luigi, Tifernina; 6) L'attentato dell'Intendenza della provincia, dal sigillo Id. Ifarschiezek id, id. id. Ferdinando, Franciosa Angelo, id. di Ponticelli; resulti avere il candidato durante il suo tirostaio 18 Numero DCCCLV (Barie 2·, parte supple- colta n bl•delle leggi e dei decreti del Re- (Treno). quale Merolillo Vincenzo, id. di Pastorano; date prove di subor ••in=n, di intelligenza o di so- d'Italia, mandando a ebinnqaw spetti di Ge-let omdare) deRa Raccolta sfjeiale deRe leggi e dei gno Gr6eo Andrea, id. di Montesano; lorsia nell'adelopimento de' suoi doveri; esservarlo e di Tenente al di decreti del RegNO CONAÑ€¾Q $1 idgNdMitÊtgfdiO farlo osservare. -

Production Offshoring and the Skill Composition of Italian Manufacturing Firms: a Counterfactual Analysis

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Antonietti, Roberto; Antonioli, Davide Working Paper Production Offshoring and the Skill Composition of Italian Manufacturing Firms: A Counterfactual Analysis Nota di Lavoro, No. 97.2007 Provided in Cooperation with: Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (FEEM) Suggested Citation: Antonietti, Roberto; Antonioli, Davide (2007) : Production Offshoring and the Skill Composition of Italian Manufacturing Firms: A Counterfactual Analysis, Nota di Lavoro, No. 97.2007, Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei (FEEM), Milano This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/74177 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen -

Intestinal Permeability

Bischoff et al. BMC Gastroenterology 2014, 14:189 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-230X/14/189 REVIEW Open Access Intestinal permeability – a new target for disease prevention and therapy Stephan C Bischoff1*, Giovanni Barbara2, Wim Buurman3, Theo Ockhuizen4, Jörg-Dieter Schulzke5, Matteo Serino6, Herbert Tilg7, Alastair Watson8 and Jerry M Wells9 Abstract Data are accumulating that emphasize the important role of the intestinal barrier and intestinal permeability for health and disease. However, these terms are poorly defined, their assessment is a matter of debate, and their clinical significance is not clearly established. In the present review, current knowledge on mucosal barrier and its role in disease prevention and therapy is summarized. First, the relevant terms ‘intestinal barrier’ and ‘intestinal permeability’ are defined. Secondly, the key element of the intestinal barrier affecting permeability are described. This barrier represents a huge mucosal surface, where billions of bacteria face the largest immune system of our body. On the one hand, an intact intestinal barrier protects the human organism against invasion of microorganisms and toxins, on the other hand, this barrier must be open to absorb essential fluids and nutrients. Such opposing goals are achieved by a complex anatomical and functional structure the intestinal barrier consists of, the functional status of which is described by ‘intestinal permeability’. Third, the regulation of intestinal permeability by diet and bacteria is depicted. In particular, potential barrier disruptors such as hypoperfusion of the gut, infections and toxins, but also selected over-dosed nutrients, drugs, and other lifestyle factors have to be considered. In the fourth part, the means to assess intestinal permeability are presented and critically discussed. -

2011-01-10.Pdf

CRÊTES Cologna roi CHRISTIAN GALLEY La neige disparaît, les cours de ski du Tour de ski Impérial dix jours en font de même... >>> PAGE 7 durant, le Grison s’est imposé une deuxième fois lors du Tour de JA ski. Du même coup, il s’échappe en tête du général de la Coupe du monde. >>> PAGE 17 0 Lundi 10 janvier 2011 ● www.arcinfo.ch ● N 7 ● CHF 2.50 / € 1.60 KEYSTONE PONTAREUSE Le secret des armoiries Lara Gut éblouissante lauréate à Altenmarkt CHRISTIAN GALLEY Les armoiries de la future commune de Pontareuse sont l’œuvre d’un habitant de Cortaillod et de son petit-fils. >>> PAGE 5 NEUCHÂTEL Drame près des Cadolles Une jeune fille de 18 ans a perdu la vie dans un accident de la route ce week-end près des Cadolles. >>> PAGE 7 ÉTATS-UNIS Fusillade meurtrière KEYSTONE Une fusillade dirigée KEYSTONE contre une élue démocrate américaine a ET DE DEUX Lara Gut a mis tout le monde d’accord lors du super-G d’Altenmarkt. La jeune Tessinoise fait six tués et douze (19 ans) s’est même permis le luxe de reléguer Lindsey Vonn à plus d’une demi-seconde. L’Obwaldienne blessés samedi à Tucson, en Arizona. >>> PAGE 24 Dominique Gisin complète le tableau en prenant la troisième place. >>> PAGE 15 VOLLEYBALL LA BRÉVINE LANGUES Métissages Le NUC a gagné Une forêt des écrivains le bon match pour les GUILLAUME PERRET romands harpistes La forêt des Cottards, au sud du lac des Taillères, VINCENT MURITH commence à fournir un précieux bois de résonance pour les luthiers. -

Le Parole Chiave Della Formazione Professionale

Le parole chiave della formazione professionale II edizione A cura di G. MALIZIA (coord.) - D. ANTONIETTI - M. TONINI Coordinamento editoriale: MALIZIA Guglielmo (Università Pontificia Salesiana, Roma), coord. TONINI Mario (Sede Nazionale CNOS-FAP) ANTONIETTI Daniela (Sede Nazionale CNOS-FAP) Comitato scientifico: PRELLEZO José Manuel (Università Pontificia Salesiana, Roma) NANNI Carlo (Università Pontificia Salesiana, Roma) SARTI Silvano (Università Pontificia Salesiana, Roma) SPAGNUOLO Giovanna (ISFOL) REGHELLIN Lucio (Sede Nazionale CNOS-FAP) VALENTE Lauretta (Sede Nazionale CIOFS/FP) ELICIO Angela (Sede Nazionale CIOFS/FP) Tip.: Istituto Salesiano Pio XI - Via Umbertide, 11 - 00181 Roma Tel. 06.78.27.819 - Fax 06.78.48.333 - E-mail: [email protected] aprile 2007 SOMMARIO PRESENTAZIONE. 5 INTRODUZIONE . 7 COLLABORATORI . 11 ABBREVIAZIONI E SIGLE . 13 VOCI . 15 PISTE DI LETTURA . 249 INDICE . 259 3 PRESENTAZIONE L’introduzione dell’Obbligo di frequenza di attività formative fino al diciotte- simo anno di età (art. 68 della Legge 17 maggio 1999, n. 144) e del successivo Di- ritto all’istruzione e alla formazione per almeno dodici anni o, comunque, sino al conseguimento di una qualifica entro il diciottesimo anno di età (Legge 53/03 e D.Lgs. 76/2005) hanno impegnato il CNOS-FAP e il CIOFS/FP nella progetta- zione, sperimentazione e valutazione di nuovi percorsi formativi prefigurati dalla normativa. Uno dei risultati di questo complesso e stimolante processo di rinnova- mento della Formazione Professionale Iniziale (FPI) è stata l’organizzazione -

COLLOQUI SETTIMANALI A.S. 2019/20 Istituto D'istruzione Superiore

Istituto d’Istruzione Superiore COLLOQUI SETTIMANALI A.S. 2019/20 Istituto d’Istruzione Superiore “G. Antonietti”- Iseo “G. Antonietti”- Iseo DOCENTE GIORNO ORARIO PIANO Istituto d’IstruzioneACCETTO Superiore MARIAROSARIA VENERDÌ 10:00 - 10:55 PT “G. Antonietti”AGOSTI- Iseo GIOVANMARIA MARTEDÌ 12:00 - 12:55 PT ALBERTI MARIACRISTINA LUNEDÌ 11:05 - 12:00 PT ALLEGRI MICHAELA LUNEDÌ 10:00 - 10:55 PT AMOROSO ETTOREALFONSO MARTEDÌ 09:05 - 10:00 PT ANGELILLO INES VENERDÌ 12:00 - 12:55 PT ARCHETTI MAURO GIOVEDÌ 10:00 - 10:55 PT AVENA MARIA GRAZIA MARTEDÌ 09:05 - 10:00 PT BARRANO GIUSEPPE MARTEDÌ 11:05 - 12:00 PT BARTOLINI LUCA GIOVEDÌ 10:00 - 10:55 PT BARUCCO MARA LUNEDÌ 12:00 - 12:55 PT BAZZANI ROBERTA MERCOLEDÌ 12:00 - 12:55 PT BELLERI LUISA LUNEDÌ 11:05 - 12:00 PT BELLI LAURA MARTEDÌ 09:05 - 10:00 PT BELOTTI ROSSANA MARTEDÌ 11:05 - 12:00 PT BIANCHETTI FRANCESCO MERCOLEDÌ 11:05 - 12:00 PT BILLIA MANUEL FRANCISCO MERCOLEDÌ 12:55 - 13:45 PT BIONDI MILENA VENERDÌ 12:00 - 12:55 PT BLANZUOLI RAFFAELLA GIOVEDÌ 11:05 - 12:00 PT BORGHESI ELISABETTA VENERDÌ 10:00 - 10:55 PT BUFFOLI ALESSANDRA LUNEDÌ 12:55 - 13:45 PT CALIMERI STEFANO SABATO 11:05 - 12:00 PT CANNELLA GIUSEPPE VENERDÌ 09:05 - 10:00 1 CANTELLO CINZIA MARTEDÌ 10:00 - 10:55 PT CAPOLONGO GIUSEPPINA VENERDÌ 11:05 - 12:00 PT CAPUZZO CRISTIAN VENERDÌ 09:05 - 10:00 PT CARASTRO VINCENZA MARIA MERCOLEDÌ 09:05 - 10:00 PT CARPENZANO GIORGIO MERCOLEDÌ 10:00 - 10:55 PT CASSINA LUIGI MERCOLEDÌ 10:00 - 10:55 PT CINONI MAURA MARTEDÌ 11:05 - 12:00 PT CIVIDATI ALBERTO VENERDÌ 12:55 - 13:45 PT COLOSIO LUISA -

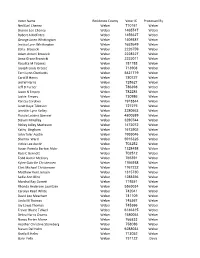

Valid Signers Januar

Voter Name Residence County Voter ID Processed By Neil Earl Cheney Weber 710161 Weber Sharon Lee Cheney Weber 1465747 Weber Robert A McEntee Weber 1459327 Weber George Jaren Whittington Weber 1409387 Weber Jessica Lynn Whittington Weber 1652649 Weber Zofia Brzezicki Weber 2226759 Weber Adam Antoni Brzezicki Weber 2228327 Weber Anna Grace Brzezicki Weber 2222011 Weber Rosalita M Tabarez Weber 781788 Weber Joseph Louis Orozco Weber 713908 Weber Terri Lynn Checketts Weber 5831719 Weber Carol B Harris Weber 780727 Weber Jed W Harris Weber 728627 Weber Jeff D Turner Weber 786398 Weber Jason N Empey Weber 782284 Weber Jackie Empey Weber 730986 Weber Kari Su Cordova Weber 1918844 Weber Janet Kaye Tillotson Weber 727275 Weber Jennifer Lynn Kelley Weber 3280663 Weber Flossie Louana Spencer Weber 4800589 Weber Steven M Kelley Weber 3280744 Weber Rickey Jolley Matheson Weber 1473072 Weber Kathy Bingham Weber 1673902 Weber John Tyler Austin Weber 1955046 Weber Shamra Ward Weber 5915325 Weber Vickie Lee Austin Weber 703252 Weber Susan Pamela Barton-Alder Weber 1328458 Weber Ross C Bennett Weber 702512 Weber Todd Austin McCrary Weber 765391 Weber Kylee Gabrille Christensen Weber 1766938 Weber Clint Michael Christensen Weber 1767222 Weber Matthew Kent Jensen Weber 1315730 Weber Sadie Ann Blind Weber 1288356 Weber Marshal Ray Garrett Weber 719351 Weber Rhonda Anderson Lauritzen Weber 5865034 Weber Carolyn Read White Weber 742041 Weber David Lee Meacham Weber 741109 Weber Linda M Thomas Weber 745367 Weber Jay Lewis Thomas Weber 745366 Weber Trevor Blaine -

Lazzarini, Isabella. Il Linguaggio Del Territorio Fra Principe E Comunità

[https://commons.warburg.sas.ac.uk/downloads/5t34sj573] Lazzarini, Isabella. Il linguaggio del territorio fra principe e comunità. 2009 Book Abstract: In April 1479, the communities of the marquisate of Mantua pronounced for the first time a general oath of fealty to Federico Gonzaga, the third marquis, inaugurating a custom that was to be repeated with relative regularity in the following decades every time a Prince died. It was a practice which was fairly new for the Gonzago marquisate, at least in this capillary and general extension to the entire body of the State. The significance of an innovation of this kind deserves attention, as do the genesis and the partial forms that preceded this mature expression. This book comprises an edition of the entire related documentary corpus, complete with photographic reproductions of the individual documents, and preceded by a substantial introduction in which the event is described, placed in context and interpreted from various points of view. Le comunità del marchesato di Mantova pronunciarono per la prima volta un generale giuramento di fedeltà a Federico Gonzaga terzo marchese nell'aprile 1479, inaugurando un uso che si sarebbe ripetuto con relativa continuità nei decenni successivi ad ogni morte del principe. Si tratta di una pratica relativamente nuova per il marchesato gonzaghesco, almeno in questa capillare e generale estensione all'intero corpo dello stato: il significato di una innovazione di questo genere merita attenzione, come anche la genesi e le forme parziali che hanno preceduto questa forma matura. In questo volume si dà l'edizione dell'intero corpus documentario relativo, integrata dalla riproduzione fotografica dei singoli documenti, e preceduta da una corposa introduzione che punta a inserire il case- study mantovano nel recente, articolato dibattito intorno alla costruzione e alla crescita di linguaggi politici diversificati nel tardo medioevo italiano. -

Crystallization of Complex Inorganic Systems Within the Confinement of Miniemulsion Droplets

Crystallization of Complex Inorganic Systems within the Confinement of Miniemulsion Droplets Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades „Doktor der Naturwissenschaften“ im Promotionsfach Chemie am Fachbereich Chemie, Pharmazie und Geowissenschaften der Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz vorgelegt von Alice Antonello geboren in Busto Arsizio, Italien Mainz, Mai 2017 Dekanin: 1. Berichterstatterin 2. Berichterstatterin Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 29.06.2017 I hereby declare that I wrote the dissertation submitted without any unauthorized external assistance and used only sources acknowledged in the work. All textual passages which are appropriated verbatim or paraphrased from published and unpublished texts as well as all information obtained from oral sources are duly indicated and listed in accordance with bibliographical rules. In carrying out this research, I complied with the rules of standard scientific practice as formulated in the statutes of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz to ensure standard scientific practice. Mainz, May 2017 Abstract Nanometric confinement strongly affects crystallization processes. In the small volume of miniemulsion droplets, precursor concentrations are limited and, consequently, the crystal growth is slowed down and smaller crystals are obtained. In an ideal case, each miniemulsion droplet can act as an independent “nanoreactor” because it is stable against molecular diffusion and, therefore, without exchange of material among the droplets, the particles grow only from the initial quantity of precursors. Furthermore, confinement controls the particle size by delimiting the maximum space where the crystallization can occur. This dissertation demonstrates this control of growth and size through the crystallization of ferrites, ammonium phosphomolybdates (APM), and manganites within miniemulsion droplets. All the materials were obtained as nanoparticles with dimensions below 100 nm. -

Carbon-Based Photocathode Materials for Solar Hydrogen Production

Carbon-based Photocathode Materials for Solar Hydrogen Production Sebastiano Bellani, Maria Rosa Antognazza, and Francesco Bonaccorso* Dr. S. Bellani, Dr. F. Bonaccorso Graphene Labs, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, via Morego 30, 16163 Genova, Italy E-mail: [email protected] Dr. F. Bonaccorso BeDimensional Srl, via Albisola 121, 16163, Genova, Italy. Dr. M. R. Antognazza Center for Nano Science and Technology @Polimi, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, via Pascoli 70/3, 20133 Milano, Italy Abstract Hydrogen is considered a promising environmentally friendly energy carrier for replacing traditional fossil fuels. In this context, photoelectrochemical (PEC) cells effectively convert solar energy directly to H2 fuel by water photoelectrolysis, thereby monolitically combining the functions of both light harvesting and electrolysis. In such devices, photocathodes and photoanodes carry out hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER), respectively. Here, we focus on photocathodes for HER, traditionally based on metal oxides, III–V group and II–VI group semiconductors, Si and copper-based chalcogenides as photoactive material. Recently, carbon-based materials have emerged as reliable alternatives to the aforementioned materials. Here, we provide a perspective on carbon-based photocathodes, critically analysing recent research progresses and outlining the major guidelines for the development of efficient and stable photocathode architectures. In particular, we discuss the functional role of charge-selective and protective layers, which enhance both the efficiency and the durability of the photocathodes. We afford an in-depth evaluation of the state-of-the-art fabrication of photocathodes through scalable, high-troughput, cost-effective methods. The most critical issues regarding the recently developed light-trapping nanostructured architectures are also addressed.