Descriptions of Nuclear Explosions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Characterizing Explosive Effects on Underground Structures.” Electronic Scientific Notebook 1160E

NUREG/CR-7201 Characterizing Explosive Effects on Underground Structures Office of Nuclear Security and Incident Response AVAILABILITY OF REFERENCE MATERIALS IN NRC PUBLICATIONS NRC Reference Material Non-NRC Reference Material As of November 1999, you may electronically access Documents available from public and special technical NUREG-series publications and other NRC records at libraries include all open literature items, such as books, NRC’s Library at www.nrc.gov/reading-rm.html. Publicly journal articles, transactions, Federal Register notices, released records include, to name a few, NUREG-series Federal and State legislation, and congressional reports. publications; Federal Register notices; applicant, Such documents as theses, dissertations, foreign reports licensee, and vendor documents and correspondence; and translations, and non-NRC conference proceedings NRC correspondence and internal memoranda; bulletins may be purchased from their sponsoring organization. and information notices; inspection and investigative reports; licensee event reports; and Commission papers Copies of industry codes and standards used in a and their attachments. substantive manner in the NRC regulatory process are maintained at— NRC publications in the NUREG series, NRC regulations, The NRC Technical Library and Title 10, “Energy,” in the Code of Federal Regulations Two White Flint North may also be purchased from one of these two sources. 11545 Rockville Pike Rockville, MD 20852-2738 1. The Superintendent of Documents U.S. Government Publishing Office These standards are available in the library for reference Mail Stop IDCC use by the public. Codes and standards are usually Washington, DC 20402-0001 copyrighted and may be purchased from the originating Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov organization or, if they are American National Standards, Telephone: (202) 512-1800 from— Fax: (202) 512-2104 American National Standards Institute 11 West 42nd Street 2. -

Operation Dominic I

OPERATION DOMINIC I United States Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Tests Nuclear Test Personnel Review Prepared by the Defense Nuclear Agency as Executive Agency for the Department of Defense HRE- 0 4 3 6 . .% I.., -., 5. ooument. Tbe t k oorreotsd oontraofor that tad oa the book aw ra-ready c I I i I 1 1 I 1 I 1 i I I i I I I i i t I REPORT NUMBER 2. GOVT ACCESSION NC I NA6OccOF 1 i Technical Report 7. AUTHOR(.) i L. Berkhouse, S.E. Davis, F.R. Gladeck, J.H. Hallowell, C.B. Jones, E.J. Martin, DNAOO1-79-C-0472 R.A. Miller, F.W. McMullan, M.J. Osborne I I 9. PERFORMING ORGAMIIATION NWE AN0 AODRCSS ID. PROGRAM ELEMENT PROJECT. TASU Kamn Tempo AREA & WOW UNIT'NUMSERS P.O. Drawer (816 State St.) QQ . Subtask U99QAXMK506-09 ; Santa Barbara, CA 93102 11. CONTROLLING OFClCC MAME AM0 ADDRESS 12. REPORT DATE 1 nirpctor- . - - - Defense Nuclear Agency Washington, DC 20305 71, MONITORING AGENCY NAME AODRCSs(rfdIfI*mI ka CamlIlIU Olllc.) IS. SECURITY CLASS. (-1 ah -*) J Unclassified SCHCDULC 1 i 1 I 1 IO. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES This work was sponsored by the Defense Nuclear Agency under RDT&E RMSS 1 Code 6350079464 U99QAXMK506-09 H2590D. For sale by the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA 22161 19. KEY WOROS (Cmlmm a nm.. mid. I1 n.c...-7 .nd Id.nllh 4 bled nlrmk) I Nuclear Testing Polaris KINGFISH Nuclear Test Personnel Review (NTPR) FISHBOWL TIGHTROPE DOMINIC Phase I Christmas Island CHECKMATE 1 Johnston Island STARFISH SWORDFISH ASROC BLUEGILL (Continued) D. -

US5212343.Pdf

|||||I|||||| USOO5212343A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,212,343 Brupbacher et al. 45) Date of Patent: May 18, 1993 54 WATER REACTIVE METHOD WITH 3,377,955 4/1968 Hodgson ............................. 102/102 DELAYED EXPLOSION 3,388,554 6/1968 Hodgson ............................... 60/217 3,986,909 10/1976 Macri....... ... 149/19.9 75) Inventors: John M. Brupbacher, Catonsville; 4,034,497 7/1977 Yanda ........... ... 42/1 G Leontios Christodoulou, Baltimore, 4,188,884 2/1980 White et al. 102/54 both of Md.; James M. Patton, 4,280,409 7/1981 Rozner et al. ... 02/364 Annandale, Va.; Russell N. Bennett, 4,331,080 5/1982 West et al..... ... 102/301 Baltimore, Md.; Alvin F. Bopp; Larry 4,432,818 2/1984 Givens .................................. 149/22 G. Boxall, both of Catonsville, Md.; Primary Examiner-Peter A. Nelson William M. Buchta, Ellicott City, Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Gay Chin; Bruce M. Md. Winchell; Alan G. Towner 73) Assignee: Martin Marietta Corporation, 57 ABSTRACT Bethesda, Md. Devices and methods are disclosed for contacting a hot (21) Appl. No.: 573,960 reaction mass with water to initiate an explosive reac ar. tion. The reaction mass comprises a ceramic or interme (22 Filed: Aug. 27, 1990 tallic material that is produced by exothermically react 51) Int. Cl........................... F42B3/00; F42B 13/14 ing a mixture of reactive elements. Suitable reaction 52 U.S. C. .................................... 102/323; 102/302; masses include borides and/or carbides that are formed 102/364; 149/22; 149/108.2; 42/1.14 by reacting a mixture comprising B and/or C in combi 58) Field of Search ............... -

The Uncertain Consequences of Nuclear Weapons Use

THE UNCERTAIN CONSEQUENCES OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS USE Michael J. Frankel James Scouras George W. Ullrich Copyright © 2015 The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory LLC. All Rights Reserved. NSAD-R-15-020 THE UNCERTAIN CONSEQUENCES OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS USE iii Contents Figures ................................................................................................................................................................................................ v Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................................................vii Overview ....................................................................................................................................................................1 Historical Context .....................................................................................................................................................2 Surprises ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Enduring Uncertainties, Waning Resources ................................................................................................................10 Physical Effects: What We Know, What Is Uncertain, and Tools of the Trade .............................................. 12 Nuclear Weapons Effects Phenomena...........................................................................................................................13 -

A Novel Vision-Based Classification System for Explosion Phenomena

Journal of Imaging Article A Novel Vision-Based Classification System for Explosion Phenomena Sumaya Abusaleh *, Ausif Mahmood, Khaled Elleithy and Sarosh Patel Computer Science and Engineering Department, University of Bridgeport, Bridgeport, CT 06604, USA; [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (K.E.); [email protected] (S.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-203-543-9085 Academic Editor: Gonzalo Pajares Martinsanz Received: 4 October 2016; Accepted: 10 April 2017; Published: 15 April 2017 Abstract: The need for a proper design and implementation of adequate surveillance system for detecting and categorizing explosion phenomena is nowadays rising as a part of the development planning for risk reduction processes including mitigation and preparedness. In this context, we introduce state-of-the-art explosions classification using pattern recognition techniques. Consequently, we define seven patterns for some of explosion and non-explosion phenomena including: pyroclastic density currents, lava fountains, lava and tephra fallout, nuclear explosions, wildfires, fireworks, and sky clouds. Towards the classification goal, we collected a new dataset of 5327 2D RGB images that are used for training the classifier. Furthermore, in order to achieve high reliability in the proposed explosion classification system and to provide multiple analysis for the monitored phenomena, we propose employing multiple approaches for feature extraction on images including texture features, features in the spatial domain, and features in the transform domain. Texture features are measured on intensity levels using the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) algorithm to obtain the highest 100 eigenvectors and eigenvalues. Moreover, features in the spatial domain are calculated using amplitude features such as the YCbCr color model; then, PCA is used to reduce vectors’ dimensionality to 100 features. -

Thermo-Gas Dynamics of Hydrogen Combustion and Explosion

Shock Wave and High Pressure Phenomena Thermo-Gas Dynamics of Hydrogen Combustion and Explosion Bearbeitet von Boris E. Gelfand, Mikhail V. Silnikov, Sergey P. Medvedev, Sergey V. Khomik 1. Auflage 2012. Buch. xxii, 326 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 642 25351 5 Format (B x L): 15,5 x 23,5 cm Gewicht: 684 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Technik > Werkstoffkunde, Mechanische Technologie > Technische Thermodynamik schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Contents 1 Fundamental Combustion Characteristics of Hydrogenous Mixtures ................................................................... 1 1.1 Laminar Flame Velocity ............................................... 1 1.2 Flame Stretch Rate (Stretch Effect) ................................... 1 1.3 Markstein Length ...................................................... 3 1.4 Lewis Number and Selective Diffusion ............................... 4 1.5 Diffusion-Thermal and Hydrodynamic Flame Instability ............. 5 1.6 Turbulent Flame Velocity ............................................. 6 1.7 Mixture Composition .................................................. 7 1.8 Macroscopic Combustion Parameters of Hydrogenous Mixtures ............................................................... -

Nuclear Tsunami: Myth Or Reality?

AUTHOR: Elmas Hasanovikj, MIS Program Coordinator NUCLEAR TSUNAMI: MYTH OR REALITY? Analysis of the likelihood nuclear bombs to produce earthquake and devastating tsunami. I. The long lasting dream of Russian’s in heaving nuclear torpedo with devastating power. The idea of having super-powerful nuclear torpedo originates from the prominent nuclear physics Andrei Sakharov, who also played a crucial role in building the biggest nuclear bomb ever built - the Tsar Bomba. In particular, Sakharov in his Memoir explains how he came up to the idea of building nuclear torpedo. As Sakharov stressed, after the test of the Big Bomb he was “concerned that the military couldn’t use it without an effective carrier”, because a “bomber would be too easy to shoot down” (Shakarov, 1990, pp.220). Thus, his idea was building giant torpedo that will be launched by a submarine that would be capable of carrying 100-megaton nuclear warhead, which will have strong enough body to withstand the exploding mines, fitted with an atomic-powered jet engine that will enable the torpedo to travel long distances to reach their targets (harbors), and capable to detonate both in air and underwater. However, Sakharov gave up on his idea after the conversation that he had with the Rear Admiral Fomin. In the conversation, Admiral Fomin told Sakharov that he is “shocked and disgusted by the idea of merciless mass slaughter, and remarked that the officers and sailors of the fleet were accustomed to fighting only armed adversaries, in open battle” (Sakharov, 1990, pp.221). After this conversation, Sakharov hadn’t discussed this idea with anyone else because he considered that it would be foolish wasting “extravagant sums required on research and development work on such torpedoes”, because he feared that this project “couldn’t be kept in secret (among other reasons, because radioactive contamination of the ocean would be inevitable), and contra-measures (nuclear mines, for instance) could easily be devised to detect and destroy the torpedoes enroute to their targets” (Sakharov, 1990, pp.221). -

The 22 September 1979 Vela Incident

SCIENCE & GLOBAL SECURITY , VOL. , NO. , – https://doi.org/./.. The September Vela Incident: Radionuclide and Hydroacoustic Evidence for a Nuclear Explosion Lars-Erik De Geer a and Christopher M. Wrightb aRetired, Swedish Defence Research Agency, Stockholm, Sweden and The Preparatory Commission for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization, Vienna, Austria; bUNSW Canberra, School of Physical, Environmental and Mathematical Sciences, Research Group on Science & Security, The Australian Defence Force Academy, Canberra BC, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This article offers a new analysis of radionuclide and hydroacous- tic data to support a low-yield nuclear weapon test as a plausi- ble explanation for the still contentious 22 September 1979 Vela Incident, in which U.S. satellite Vela 6911 detected an optical sig- nal characteristic of an atmospheric nuclear explosion over the Southern Indian or Atlantic Ocean. Based on documents not pre- viously widely available, as well as recently declassified papers and letters, this article concludes that iodine-131 found in the thy- roids of some Australian sheep would be consistent with them having grazed in the path of a potential radioactive fallout plume from a 22 September low-yield nuclear test in the Southern Indian Ocean. Further, several declassified letters and reports which describe aspects of still classified hydroacoustic reports and data favor the test scenario. The radionuclide and hydroacoustic data taken together with the analysis of the double-flash optical sig- nal picked up by Vela 6911 that was described in a companion 2017 article (“The 22 September 1979 Vela Incident: The Detected Double-Flash”) can be traced back to sources with similar spatial and temporal origins and serve as a strong indicator for a nuclear explosion being responsible for the 22 September 1979 Vela Incident. -

Suggestions for Inclusion in The

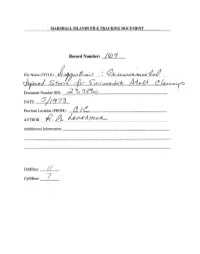

MARSHALL ISLANDS FILE TRACKING DOCUMENT Record Number: /63s DATE: s,/h9 73 Previous Location (FROM): e le Addditional Information: OrMIbox: f4/ ,- CyMIbox: 7 239830 17 May 1973 _ r IN TtiE ENIWETOK ATOLL CLEANUP : R. B. Leachman 3.f. The U, S: Devclog~+n'~-_--L of the Is_landsfor Nuclear Testing The testing of nuclear detonation requires testing grounds that, among other factors, are remote from populated areas. Previously, two tests had been conducted at Bikini Atoll in June and July 1946 under Operation Crossroads and, earlier, near Alamogordo, New Mexico on 16 July 7945 as Operation Trinity. However, for a continuing ! program of testing, Bikini suffered deficiencies in that the land .._..--.,_.._ *** I. al.._.‘ryl L IIL I LIICI ;ar-ye WJU~~I nor properly oriented to the prevailir,~ winds to permit construction of a major airstrip.' This led to the selection of Eniwetok Atoll for testing nuclear detonations,--_ a selection administratively approved by President Trumah on 2 December 1947. BEST AVAILA@k. The selection of Eniwetok Atoll was based on a study of possible ocean sites made by Captain J. S.'Russell, USN, Deputy Director of the Division of Military Applications, and by Dr. Darol K. Froman of the I Los Alamos Scientific Latoratory. In regard to possible fallout, Eniwetok Atoll was well located by having hundreds of miles of bpen sea , lying from the Atoll in the westwardly direction of the prevailing winds. 1,. Proving Ground (U. of Washington Press, Seattle, 1962) i p 81. The first of the $rc;cpsassrztilbied to conduct nuclear weapons tests on Eni\::etokAtoll nrga!iizaticilsl!ycame into being on 18 October 1947. -

3.1 Sediments and Water Quality

3.1 Sediments and Water Quality NORTHWEST TRAINING AND TESTING FINAL EIS/OEIS OCTOBER 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3.1 SEDIMENTS AND WATER QUALITY ............................................................................................... 3.1-1 3.1.1 INTRODUCTION AND METHODS ......................................................................................................... 3.1-1 3.1.1.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 3.1-1 3.1.1.2 Methods ................................................................................................................................... 3.1-9 3.1.2 AFFECTED ENVIRONMENT ............................................................................................................... 3.1-11 3.1.2.1 Sediments in the Study Area .................................................................................................. 3.1-11 3.1.2.2 Marine Debris, Military Expended Materials, and Marine Sediments .................................. 3.1-19 3.1.2.3 Climate Change and Sediments ............................................................................................. 3.1-20 3.1.2.4 Water Quality in the Study Area ............................................................................................ 3.1-21 3.1.2.5 Marine Debris and Marine Water Quality ............................................................................. 3.1-27 3.1.2.6 Climate Change and Marine Water Quality .......................................................................... -

The Archeology of the Atomic Bomb

THE ARCHEOLOGY OF THE ATOMIC BOMB: A SUBMERGED CULTURAL RESOURCES ASSESSMENT OF THE SUNKEN FLEET OF OPERATION CROSSROADS AT BIKINI AND KWAJALEIN ATOLL LAGOO NS REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ISLANDS Prepared for: The Kili/Bikini/Ejit Local Government Council By: James P. Delgado Daniel J. Lenihan (Principal Investigator) Larry E. Murphy Illustrations by: Larry V. Nordby Jerry L. Livingston Submerged Cultural Resources Unit National Maritime Initiative United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers Number 37 -Santa Fe, New Mexico 1991 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . iii FOREWORD . vii Secretary of the Interior, Manuel Lujan, Jr. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................... ix CHAPTER ONE: Introduction . 1 Daniel J. Lenihan Project Mandate and Background . 1 Methodology . 4 Activities . 7 CHAPTER TWO: Operation Crossroads . 11 James P. Delgado The Concept of a Naval Test Evolves . 14 Preparing for the Tests . 18 The Able Test . 23 The Baker Test . 27 Decontamination Efforts . 29 The Legacy of Crossroads . 31 The 1947 Scientific Resurvey . 34 CHAPTER THREE: Ship's Histories for the Sunken Vessels 43 James P. Delgado USS Saratoga ............... .... ......................... 43 USS Arkansas . 52 HIJMS Nagato . 55 HIJMS Sakawa . 59 USS Prinz Eugen . 60 USS Anderson . 64 USS Lamson . 66 USS Apogon . 70 USS Pilotfish . 72 USS Gilliam . 73 USS Carlisle . 74 ARDC-13 ................................................. 76 Y0-160 .................................................. 76 LCT-414, 812, 1114, 1175, and 1237 . 77 CHAPTER FOUR: Site Descriptions . 85 James P. Delgado and Larry E. Murphy Introduction . 85 Reconstructing the Nuclear Detonations . 86 Site Descriptions: Vessels Lost During the Able Test . 90 USS Gilliam . 90 e USS Carlisle . 92 Site Descriptions: Vessels Lost During the Baker Test . -

The Humanitarian Impact and Implications of Nuclear Test Explosions in the Pacific Region Tilman A

International Review of the Red Cross (2015), 97 (899), 775–813. The human cost of nuclear weapons doi:10.1017/S1816383116000163 The humanitarian impact and implications of nuclear test explosions in the Pacific region Tilman A. Ruff* Dr Tilman A. Ruff is an infectious diseases and public health physician. Dr Ruff is Associate Professor at the Nossal Institute for Global Health, University of Melbourne; Co- President of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War; Founding Chair of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons; and International Medical Adviser for Australian Red Cross. Abstract The people of the Pacific region have suffered widespread and persisting radioactive contamination, displacement and transgenerational harm from nuclear test explosions. This paper reviews radiation health effects and the global impacts of nuclear testing, as context for the health and environmental consequences of nuclear test explosions in Australia, the Marshall Islands, the central Pacific and French Polynesia. The resulting humanitarian needs include recognition, accountability, monitoring, care, compensation and remediation. Treaty architecture to comprehensively prohibit nuclear weapons and provide for their elimination is considered the most promising way to durably end nuclear testing. Evidence of the * This paper is humbly dedicated to the victims and survivors of nuclear explosions worldwide working for the eradication of nuclear weapons. The author thanks Nic Maclellan for his helpful suggestions. © icrc 2016